the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

A sub-fossil coral Sr∕Ca record documents northward shifts of the Tropical Convergence Zone in the eastern Indian Ocean

Miriam Pfeiffer

Hideko Takayanagi

Lars Reuning

Takaaki K. Watanabe

Saori Ito

Dieter Garbe-Schönberg

Tsuyoshi Watanabe

Chung-Che Wu

Chuan-Chou Shen

Jens Zinke

Geert-Jan A. Brummer

Sri Yudawati Cahyarini

Sea surface temperature (SST) variability in the south-eastern tropical Indian Ocean is crucial for rainfall variability in Indian Ocean rim countries. A large body of literature has focused on zonal variability associated with the Indian Ocean Dipole (IOD) which peaks in austral spring. In today's climate, northward shifts of the Tropical Convergence Zone (TCZ) co-vary with the IOD, and it is unclear whether these shifts may also occur independently. We have developed a new monthly resolved record from a sub-fossil coral cored at Enggano Island (Sumatra, Indonesia). Core sections containing diagenetic phases are omitted from the SST reconstruction. UTh dating shows that the -based SST record extends from 1869–1918 and from 1824–1862 with a relative age uncertainty of ±3 years (2σ). At Enggano Island, coastal upwelling and cooling in austral spring impact SST seasonality and are coupled to the latitudinal position of the TCZ. The sub-fossil coral indicates an increase in SST seasonality between 1856 and 1918 relative to the 1930–2008 period. We attribute this to enhanced cooling due to stronger south-easterly (SE) winds driven by a northward shift in the TCZ in austral spring. A nearby sediment core indicates colder SSTs and a shallower thermocline prior to ∼1930. These results are consistent with an increase in the north–south SST gradient in the eastern Indian Ocean, calculated from historical temperature data, that is not seen in the zonal SST gradient. We conclude that the relationship between meridional and zonal variability in the eastern Indian Ocean is non-stationary and modulated by the long-term evolution of temperature gradients.

- Article

(16654 KB) - Full-text XML

- BibTeX

- EndNote

Sea surface temperature (SST) variability in the south-eastern (SE) tropical Indian Ocean is crucial for rainfall variability in Indian Ocean rim countries (Weller et al., 2014; Cai et al., 2013). A large body of literature has focused on the Indian Ocean Dipole (IOD) (Saji et al., 1999; Webster et al., 1999; Ummenhofer et al., 2009a, b; Cai et al., 2013; Saji and Yamagata, 2003; Behera et al., 2005; Ashok et al., 2003; Abram et al., 2020), a zonal mode characterized by a reversal of the east–west SST gradient in the tropical Indian Ocean, causing droughts in Indonesia and Australia, and enhanced rainfall and flooding in equatorial East Africa (Ummenhofer et al., 2009a, b; Saji et al., 1999; Behera et al., 2005; Ashok et al., 2003). Comparatively little attention has been paid to meridional (north–south) SST gradients and related circulation anomalies over the SE tropical Indian Ocean in austral spring, although these can also induce significant droughts in Indonesia and flooding in southern India and Sri Lanka (Weller and Cai, 2014; Weller et al., 2014). A stronger north–south SST gradient in September–November shifts the southern boundary of the Tropical Convergence Zone (TCZ; see Geen et al., 2020) northwards (Weller et al., 2014; Weller and Cai, 2014) (Figs. 1 and A1).

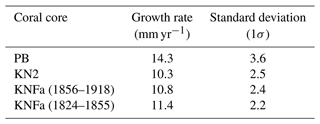

Figure 1Austral spring outgoing longwave radiation (OLR) and SST in the eastern Indian Ocean. (a) Mean September–November OLR (left panel) (Schreck et al., 2018) and Advanced Very High Resolution Radiometer (AVHRR) optimum interpolation (OI) SST (right panel) (Huang et al., 2021) from 1982–2022. (b) September–November OLR (left panel) and SST (right panel) for the moderate positive IOD (pIOD) event of 1982. (c) Same as panel (b) for the extreme pIOD event of 1994. (d) Same as panel (b) for the extreme pIOD event of 1997. (e) Same as panel (b) for the extreme pIOD event of 2006. The OLR ≤ 240 W m−2 contour (light blue) indicates the boundaries of the TCZ. Note the close correspondence of the 27 °C (stippled) and 28 °C (dashed) contours off the coast of Sumatra and the southern boundary of the TCZ. Arrows mark location of Enggano (E) and Mentawai (M). Grey boxes in panel (a) indicate the area NE (2.5–7.5° N, 90–110° E) and SE (0–10° S, 90–110° E) for the Indian Ocean SST indices used to calculate the north–south SST gradient in the eastern Indian Ocean as in Weller and Cai (2014) and Weller et al. (2014). Charts were computed at the KNMI Climate Explorer (https://climexp.knmi.nl, last access: 7 September 2024).

The eastern Indian Ocean north of 10° S features the most intense atmospheric convection in the Indian Ocean basin (Figs. 1 and A1) (Schott et al., 2009). In austral spring, meridional displacements of the TCZ are driven by ocean–atmosphere interactions in the SE tropical Indian Ocean, which include monsoon-induced coastal upwelling in September–November and active SST–thermocline feedbacks (Susanto et al., 2001; Webster et al., 1999; Cai et al., 2013; Saji and Yamagata, 2003; Weller et al., 2014). Coastal upwelling is driven by strong south-easterly (SE) winds along the coasts of Java and Sumatra associated with the South Asian summer monsoon (Susanto et al., 2001) (Figs. 2 and A2). Anomalously strong SE winds enhance coastal upwelling and cooling, which may shift the southern boundary of the TCZ to the north of 5° S and, in extreme cases, to the Equator (Figs. 1 and A1). The cooling in the SE equatorial Indian Ocean may trigger a reversal of the zonal SST gradient in the tropical Indian Ocean and the development of a positive IOD (pIOD) event (Saji et al., 1999; Fischer et al., 2005). In the satellite era, the occurrence of pIOD events and northward displacements of the southern boundary of the TCZ are tightly coupled (Weller et al., 2014; Weller and Cai, 2014), and the latter may be seen as a characteristic of pIOD events (Fig. 1). However, future projections suggest that northward shifts in the southern boundary of the TCZ may uncouple from the IOD due to the rapidly warming Asian landmass in response to greenhouse warming and, as a result, faster warming rates in the north-eastern Indian Ocean relative to the south-east (Weller and Cai, 2014; Weller et al., 2014). This could induce extreme northward shifts in the TCZ that are not associated with an increased frequency of pIOD events (Weller et al., 2014).

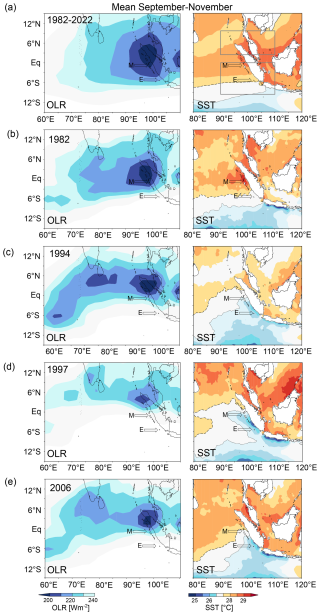

Figure 2SST seasonality and surface winds in the SE Indian Ocean. (a) The amplitude of the mean seasonal cycle of SST (in °C) decreases from >3 to 1 °C from Java to Sumatra. (b) In austral fall, mean SSTs (colors) are warm and uniform, and surface winds (vectors) are weak. (c) In austral spring, strong alongshore SE winds (vectors) lead to cooling off the coast to Java and Sumatra and large meridional differences in mean SSTs (colors). Open arrows in panels (a) and (b) mark location of Enggano (E), northern Mentawai (M), and Sumba island (S). Note the steep austral spring SST gradients around Enggano. SST data from OI SST (Reynolds et al., 2002) and wind data from Kalnay et al. (1996). Charts were computed at https://iridl.ldeo.columbia.edu/ (last access: 8 September 2024).

SST variability in the SE equatorial Indian Ocean is poorly represented in the historical gridded data of SSTs which do not adequately capture the non-linear ocean–atmosphere feedbacks in the region (Yang et al., 2020; Pfeiffer et al., 2022; Cai et al., 2013). Therefore, observational studies on the relationship between meridional and zonal SST variability are limited to the last ∼40 years in which we have satellite data of SSTs (Weller et al., 2014; Weller and Cai, 2014). Coral ratios measured at a monthly resolution were shown to provide a realistic representation of SST variability in the SE tropical Indian Ocean as, unlike historical SSTs interpolated from sparse data, the coral proxy data are not compromised by non-linear ocean–atmosphere feedbacks (Yang et al., 2020; Pfeiffer et al., 2022; Cahyarini et al., 2021). To date, however, coral studies of historical variability in the SE tropical Indian Ocean have mainly focused on zonal variability associated with the IOD (Abram et al., 2007, 2008, 2015, 2020).

Here, we present a new monthly resolved record from a sub-fossil Porites coral drilled at Enggano Island (Sumatra, Indonesia). Our new coral record derives from a large and massive colony found in a dead, partially bio-eroded, reef (Fig. 3). UTh dating indicates that the base of the coral record is 1824±3 (2σ) years old, and the youngest sections extend to the early 20th century. Extensive screening with a state-of-the-art Hitachi 3900 scanning electron microscope (SEM) was performed to identify and omit intervals with minor early marine diagenesis and to ensure the reliability of the data. After combining our new coral data with previously published coral records from Enggano Island that extend from 1930–2008 (Pfeiffer et al., 2022), we investigate the relationship between meridional and zonal SST variability in the SE Indian Ocean prior to the satellite era.

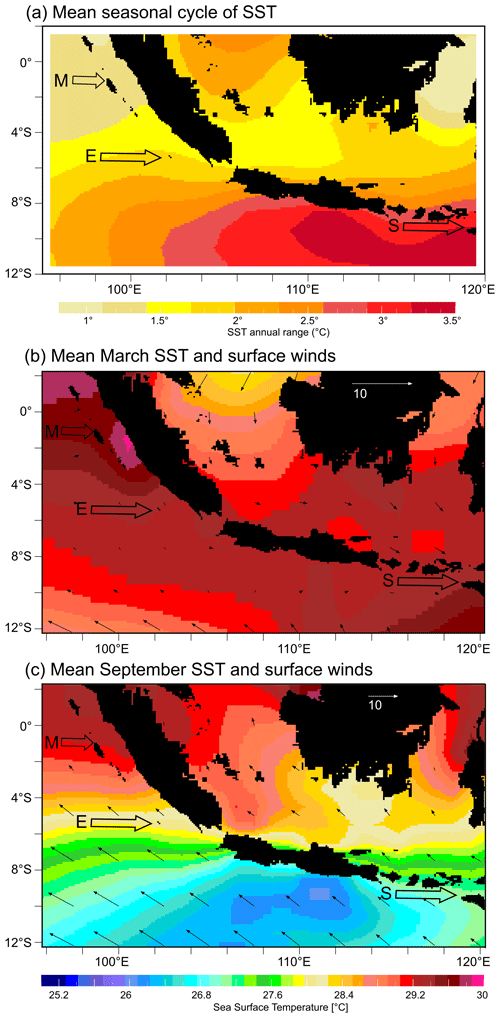

Figure 3Location and climatic setting of Enggano Island. (a) The standard deviation of September–November SST indicates areas of coastal upwelling off the coast of Java and Sumatra. (b) The skewness of September–November SSTs reflects interannual coastal upwelling events. Arrows in panels (a) and (b) mark the locations of Enggano Island (E) and northern Mentawai Island (M). Charts were computed at the KNMI Climate Explorer (https://climexp.knmi.nl, last access: 7 September 2024). (c) Mean seasonal cycles of satellite SST (thick blue lines) from northern Java to central Sumatra with 99 % confidence levels (grey shading). SST grids are selected with a latitudinal spacing of 2°, and symbols indicate their position in panels (a) and (b). Histograms show the distribution of monthly mean SSTs in the September–November season. At all sites, SST minima are ∼25 °C, but progressively higher mean September–November SSTs occur at sites north of 7° S, where only extreme pIOD events cause intense coastal upwelling. The resulting negative skewness is indicated by the 99 % confidence levels around the September–November SSTs (dashed black lines) and seen in the histograms of mean September–November SSTs. Histograms were computed using PAST (Hammer et al., 2001). SST data are from AVHRR OI SST (° grids) (Huang et al., 2021). (d) Satellite image of Enggano Island showing the fringing reefs surrounding the island from © Google Earth 2024. At its longest section, Enggano Island is 35 km long. Modern cores were drilled at the south-eastern (PB: 5°27.888′ S, 102°22.218′ E) and north-eastern (KN2: 05°21.713′ S, 102°21.511′ E) coasts. A sub-fossil coral (KNFa) was drilled next to core KN2. (e) Dead reef on the north-eastern coast of Enggano Island. (f) Bio-eroded surface of a sub-fossil coral colony with an open borehole with a diameter of 4 cm. Photos from Sri Yudawati Cahyarini.

Enggano Island lies ∼200 km off the coast of south-eastern Sumatra at 5.22° S, 102.14° E (Fig. 3). It is the southernmost island on the forearc ridge offshore of Sumatra, which also comprises the Mentawai Island chain located further north (3–1° S, 98–100° E). In austral spring, SE winds associated with the South Asian summer monsoon generate coastal upwelling and cooling off Java and Sumatra (Fig. 2) (Susanto et al., 2001). The standard deviation of monthly mean SST reveals the centers of upwelling (Figs. 3 and A2). Upwelling first develops off the coast of Java in June and then propagates north-westwards (Fig. A2). It reaches Enggano in July and extends to the northern Mentawai Islands in October (Fig. A2). In November–December, westerly winds terminate coastal upwelling, and SE Indian Ocean SSTs are generally warm with comparatively little spatial variability in austral fall (Fig. 2).

The strength of the SE winds in austral spring thus primarily determines the seasonal cycle of SSTs in the SE Indian Ocean, seen in a decrease in seasonality, from >3 °C off Java to ∼1.5–1.0 °C off Sumatra, which reflects spatial variations in the frequency of occurrence of coastal upwelling and cooling in September–November (Figs. 2 and 3). At Enggano, austral spring SSTs are colder than at the northern Mentawai Islands, SST seasonality is larger, and annual mean SSTs are lower (Figs. 2 and 3). Furthermore, Enggano Island is situated in a region where the magnitude of cooling during the SE monsoon (and, as a result, the amplitude of the mean seasonal cycle) changes profoundly over short distances (Fig. 2). This means that relatively small changes in the strength/extent of the SE winds should be seen in the magnitude of austral spring cooling and the amplitude of the mean seasonal cycle at Enggano Island.

Off the coast of Java, the SE winds cause strong upwelling and cooling every year (Susanto et al., 2001), and mean September–November SSTs are low (<27 °C) (Figs. 2 and 3). On interannual timescales, stronger-than-normal SE winds lead to an anomalous strengthening of coastal upwelling and cooling off Sumatra that may lead to (I) a northward shift in the southern boundary of the TCZ in austral spring (Figs. 1 and A1) (Weller et al., 2014) and (II) a reversal of the zonal SST gradient in the tropical Indian Ocean and the development of a pIOD event (Saji et al., 1999; Yang et al., 2020; Ng et al., 2015). During extreme pIOD events, the southern boundary of the TCZ shifts to the north of 5° S (Weller et al., 2014), i.e., to the north of Enggano Island. In these years, cool SSTs down to 25 °C can reach the Equator (Figs. 1 and A2). The occasional occurrence of extreme pIOD events in an equatorial region featuring warm surface waters in normal years is reflected in a strong negative skewness of September–November SSTs off Sumatra (Fig. 3) (Yang et al., 2020) and an enhanced seasonal cycle in these years. In contrast, anomalous austral spring cooling during moderate pIOD events is weaker and spatially restricted to the south-eastern coast of Sumatra, where Enggano is located, and the Java and Timor seas (Figs. 1 and A2). In addition to IOD-related SST variability (Pfeiffer et al., 2022), the corals from Enggano Island should therefore be sensitive recorders of changes in the strength of the SE winds and the latitudinal position of the southern boundary of the TCZ (Figs. 1, 2, and A1).

3.1 Coral collection

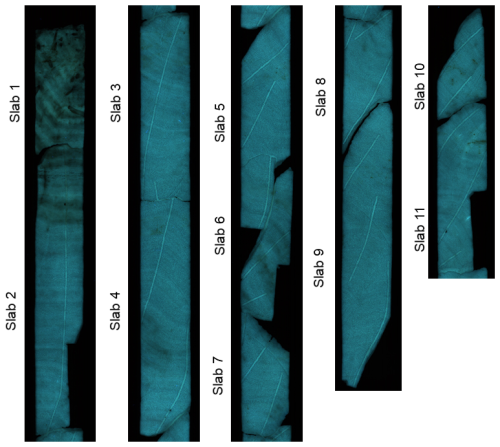

In an August 2008 field campaign, sub-fossil and dead fringing reefs were discovered around Enggano Island (Sumatra, Indonesia) at a water depth of ∼3 m (Fig. 3). A large and massive Porites coral was found, and a 1.83 m coral core (KNFa) was drilled using a pneumatic drill powered by diving tanks. After drilling, the core KNFa was cut into 5 mm thick slabs and prepared for subsampling, following standard procedures (Cahyarini et al., 2014). X-rays (Fig. 4) and luminescence scans (Fig. A4) were made at the Royal Netherlands Institute for Sea Research (NIOZ) on coral slabs to reveal the coral's seasonal banding pattern and to indicate potential zones of diagenesis. The KNFa core shows multiple density bands per year that do not allow a precise chronology based on annual bands but a good correlation of corresponding sections on adjacent coral slabs (Figs. 4 and A4).

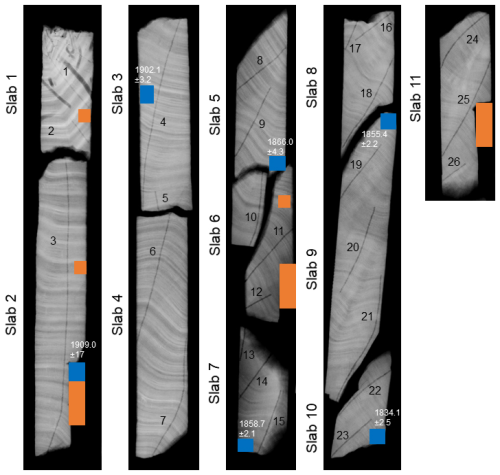

Figure 4X-ray image of the sub-fossil coral core KNFa from Enggano Island. Core slabs and sampling transects for analysis are numbered (data; see Fig. 5). Blue squares indicate samples taken for UTh dating and their ages. Note that the core shows prominent sub-annual bands that allow a good match between different slabs. Some sections of the core were cut off to assess preservation using conventional destructive methods (X-ray powder diffraction (XRD), thin-section samples, and scanning electron microscope (SEM) analysis using gold-coated stubs of coral). Small orange boxes indicate locations for SEM samples. Large orange boxes indicate locations for combined XRD, SEM, and thin-section samples. See the text for a discussion.

Two modern Porites coral samples (KN2 and PB) were collected from living corals during the same field campaign, and their records were published previously (Pfeiffer et al., 2022). The two modern corals extend from 1930–2008 and are used here for comparison with the sub-fossil coral data. See Fig. 3 for the exact location of the coral cores.

3.2 Diagenetic screening

Based on X-ray images and luminescence scans (Figs. 4 and A4), the potential diagenetic alteration was assessed, using representative samples for mineralogical and microscopic analysis. Conventional destructive analysis, including powder X-ray diffraction (XRD; n=3) and thin-section (n=3) and scanning electron microscopy (SEM; n=5), on gold-coated coral blocks (see Fig. 4 for sample location) was carried out.

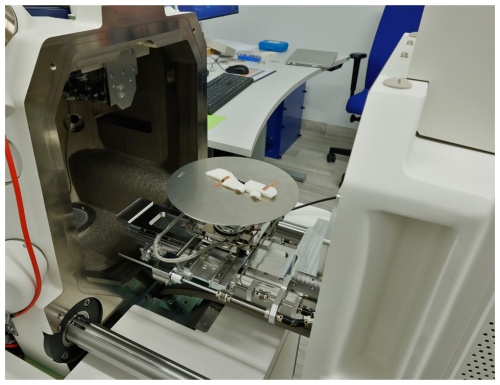

Furthermore, we conducted higher-resolution non-destructive mineralogical and microscopic analysis directly on the coral slabs parallel to the proxy sampling tracks. The 2-D XRD system Bruker D8 Advance General Area Detector Diffraction System (GADDS) was used for non-destructive XRD point measurements with a calcite detection limit of ∼0.2 % (Smodej et al., 2015). The 19 2-D XRD measurements resulted in a sampling resolution of one spot analysis every ∼7 cm. Sections showing a mottled appearance on the luminescence scans were selected for non-destructive SEM analysis with the Hitachi SU3900 system. The extra-large chamber of this SEM system can accommodate coral slabs up to 30 cm in length (Figs. A5 and A6). The analyses were carried out in low-vacuum mode (30 and 50 Pa) using an ultra-variable-pressure detector (UVD) and a backscattered electron detector (BSE). This low-vacuum mode allows the coral slabs to be analyzed continuously and directly along the proxy sample track without the need for coating with conductive materials such as gold.

3.3 analysis

The KNFa core was subsampled for analysis at 1 mm intervals, i.e., at approximately monthly resolution. For each subsample, we extracted 0.1–0.2 mg of coral powder for analysis using a handheld drill. ratios were measured at Kiel University using a Spectro Ciros CCD SOP inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometer (ICP-OES). Elemental emission signals were simultaneously collected and subsequently processed following a combination of techniques described by Schrag (1999) and de Villiers et al. (2002). The average analytical precision of measurements as estimated from sample replicates was typically around 0.08 % relative standard deviation (RSD) or colder than 0.1 °C (n>180). All coral ratios were normalized to an in-house standard calibrated against JCp-1 (8.838 mmol mol−1) (Hathorne et al., 2013). Measurements of JCp-1 had a median of 8.832 mmol mol−1 and a standard deviation of 0.009 (1σ) or 0.10 % RSD.

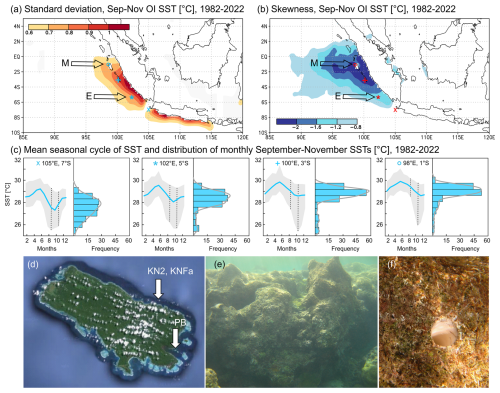

The chronology of the coral records presented in this study is developed by assigning mid-September (on average the coldest month) to the maxima. The data are then linearly interpolated to 12 monthly values per year. Average coral growth rates estimated from trace element data are larger than 10 mm yr−1 in all cores (Table A1).

3.4 UTh dating and chronology

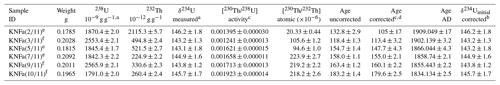

The age of KNFa was estimated by UTh dating at the National Taiwan University, following the methods of Shen et al. (2012). After chemical separation for U and Th isotopes in a clean room, the samples were analyzed with a multi-collector inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometer (MC-ICP-MS; NEPTUNE). Results are shown in Table 2.

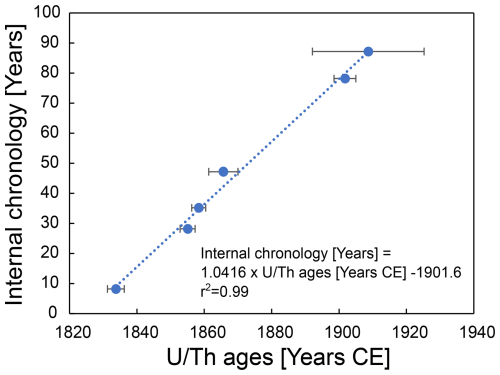

A floating chronology was estimated following the approach of Domínguez-Villar et al. (2012) (Fig. A7). The age of the coral record was estimated from the intercept of the linear regression between the UTh ages and the annual cycles of (Fig. 5), assuming that the slope of this regression is 1, using Eq. (1):

where b is the floating age. With this regression, the differences between the UTh ages and corresponding ages are minimal (0.1 years for the overall time series). The age uncertainty in the floating chronology was estimated with a Monte Carlo approach (20 000 loops) using the 2σ UTh error. The base of the KNFa record is dated to 1824±3 (2σ) years CE.

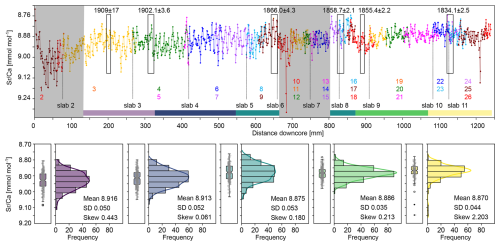

Figure 5Sub-fossil coral data of core KNFa. Top panel shows measured data of core KNFa vs. distance downcore (in mm). Each dot corresponds to one measurement. Sampling transects are highlighted by different colors and numbered (bottom) (see Fig. 4 for the location of the transect). Grey shading marks intervals discarded from further interpretation as diagenetic alterations have been detected. Sections sampled for UTh ages are shown by black rectangles. Color bars at the bottom indicate data included in the histograms, box plots, and jitter plots shown in the bottom panel. Note the reduction in the standard deviation of measured data at a depth of ∼860 mm. Histograms are computed using PAST (Hammer et al., 2001).

Combining the UTh ages with the coral density banding and growth rates suggests that the coral died in the early 1930s, although the exact timing cannot be determined due to extensive bio-erosion at the top of the coral. It is unclear what caused the death of the sub-fossil coral (and the fringing reef where the core was taken), but possible candidates include several major earthquakes centered on Enggano Island in the 1930s with magnitudes ≥ 7 (Newcomb and McCann, 1987) or severe cold anomalies, possibly coupled with red tides, due to extreme IOD-induced upwelling events (Abram et al., 2003).

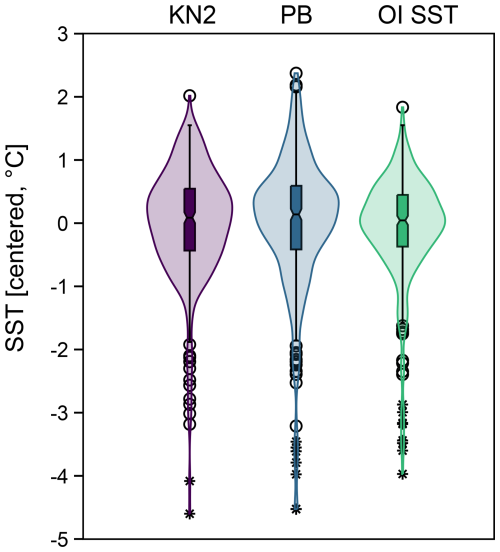

3.5 Coral –SST conversion

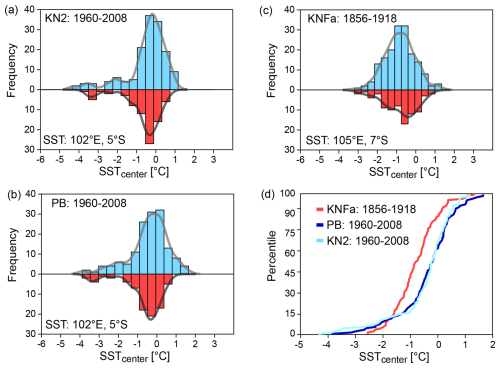

To avoid biases from so-called “vital effects” that affect mean coral ratios (e.g., Cahyarini et al., 2011; Ross et al., 2019), all coral records were centered to their mean and converted to SST units assuming a coral –SST relationship of −0.06 mmol mol−1 per 1 °C (Corrège, 2006; Ross et al., 2019; Watanabe and Pfeiffer, 2022), hereafter referred to as SSTcenter. This slope is consistent with the coral –SST calibrations of the two modern corals KN2 and PB from Enggano Island with satellite SST data (Pfeiffer et al., 2022) available since 1982. SSTcenter inferred from KN2 and PB data shows the same distribution as satellite SSTs in the grid, including Enggano Island (Pfeiffer et al., 2022) (Fig. A8).

3.6 Statistics

Distributions were visualized and compared using PAST (Hammer et al., 2001). Histograms, box plots, and violin plots were calculated using measured data prior to processing and compared with interpolated monthly data and SSTcenter inferred from coral ratios. As age model development/interpolation does not influence the spread of measured data, this allows a comparison between raw and processed records. The distribution of SSTcenter inferred from coral was compared to satellite SST (centered to its mean) using histograms, box plots, and violin plots, again circumventing potential misalignments arising from uncertainties in sub-seasonal age assignments. To test for the equality of distributions, we used the two-sample Kolmogorov–Smirnov test in PAST (Hammer et al., 2001). Means were compared using a two-sided Student t test in PAST (Hammer et al., 2001).

Mean seasonal cycles of SST were calculated from the coral data by averaging the monthly SSTcenter records. The uncertainties in this “coral climatology” were calculated using a Monte Carlo approach based on an R script (R core team, 2023) developed by Watanabe and Pfeiffer (2022) and expanded in Zinke et al. (2022); they include the analytical uncertainties in the measurements (0.08 % RSD for monthly values) and the calibration uncertainty in the –SST slope (±0.01 mmol mol−1 per 1 °C), in addition to the spread of the monthly mean data.

Wavelet power spectra (Torrence and Compo, 1998) were calculated using the biwavelet package and the R software (R core team, 2023). All wavelet analyses were based on the Morlet wavelet. The significance of power spectra was tested using the χ2 test with a 95 % significance level. The Mann–Kendall test was carried out to test the significance of trends using R software (R core team, 2023). The trend change point (Toms and Lesperance, 2003) was estimated using the SiZer package (Chaudhuri and Marron, 1999) in R (R core team, 2023). The 95 % confidence level of trend change point was generated based on a bootstrap test (n=1000).

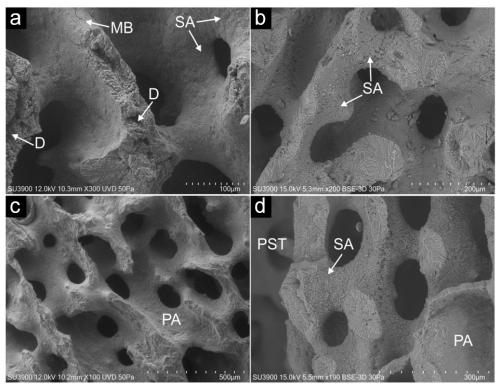

4.1 Coral preservation

The 3 conventional powder and 19 2-D XRD analyses (see Fig. 4 for location) indicate that the sub-fossil core KNFa is purely aragonitic and does not contain any calcitic phases. The analyses of the conventional SEM samples and thin sections (see Fig. 4 for location) indicate a generally excellent preservation with pristine and smooth skeletal surfaces, except for the SEM sample near the top of the coral core, which shows minor (<5 µm long) but pervasive aragonite cementation. To evaluate the extent of the potential diagenetic alteration, we scanned the entire length of the sampling tracks on slabs 1 and 2, using the uncoated coral slabs (see Sect. 3 and Figs. A5 and A6). This analysis confirmed that minor fibrous aragonite cements (5 to 10 µm long) and incipient dissolution are restricted to the upper ∼14 cm of the coral core, which also shows abundant bio-erosion traces (Fig. 4; slab 1) and a dull to mottled appearance in luminescence scans (Fig. A4). We therefore subsequently used the SEM to scan all core intervals that show similar dull colors in luminescence scans. After the proxy measurements, we additionally checked all intervals containing prominent anomalies for diagenetic changes based on SEM observations directly on the coral slabs. Using this method, we were able to identify patches of aragonite needle cements (5 to 10 µm long) (Fig. A6) that had escaped detection with our previous standard screening protocol. data from all intervals showing patchily distributed aragonite cements (sampling transects 1 and 2, top of 3, and base of 9 to top of 15; see Figs. 4 and 5) were excluded from further interpretation, since even light levels of aragonite cementation may lead to higher bulk values and consequently a cold bias in temperature reconstructions (Enmar et al., 2000; Allison et al., 2007; Hendy et al., 2007; Sayani et al., 2011).

4.2 The sub-fossil coral record

Figure 5 shows the coral data as measured along the maximum growth axis of core KNFa prior to interpolation to monthly values and prior to omitting intervals affected by diagenesis. Therefore, each dot represents one measurement of a discrete subsample. Also indicated are the slabs of the coral core and the sampling transects of analysis (in color; numbers of slabs and transects are also shown in the X-ray images; see Fig. 4). Data from overlapping transects are shown on top of each other. The first measurement on each new slab is marked as the “slab boundary”; note that these data overlap with data from the previous slab due to the coral's growth. After measuring the ratios along the entire core at 1 mm intervals, we subsequently omit data from transects where early marine diagenesis was detected by non-destructive SEM analysis from further processing (see Sect. 4.1). These sections are masked out in grey in Fig. 5.

In the intervals not affected by diagenesis, the record of KNFa shows clear seasonal cycles which can be counted visually to develop an age model. By combining this internal coral chronology with the UTh ages (see Sect. 3), we estimate that the KNFa record extends from 1824–1862 and 1869–1918 (Figs. A7, A9, and 6); i.e., it encompasses a total of 94 years with 87 years of record, with a relative age uncertainty of ±3 years (2σ). The data from well-preserved sections of the core show an excellent reproducibility between sampling transects (note that slight offsets along the x axis reflect differences in coral growth); i.e., the means and variations in measured ratios are consistent throughout the core (Fig. 5).

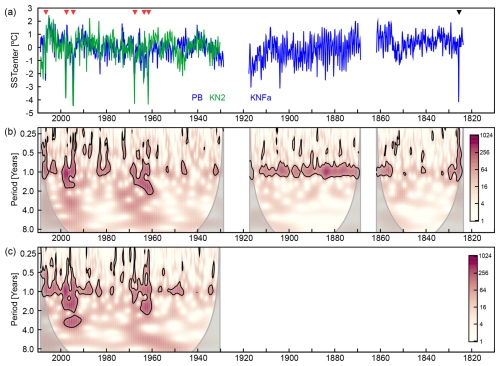

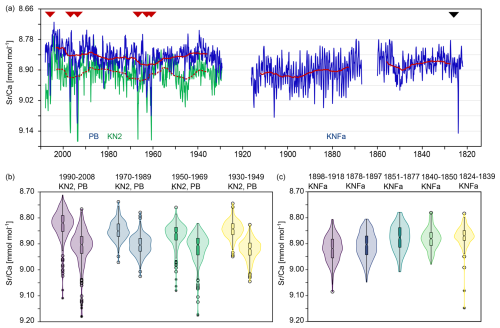

Figure 6Modern and sub-fossil monthly SSTcenter inferred from Enggano coral ratios. (a) The monthly SSTcenter record from Enggano comprises two modern (PB and KN2) and one sub-fossil core (KNFa) and extends from 1930–2008, 1869–1918, and 1824–1862. Note that the sub-fossil coral chronology is based on UTh dating with an age uncertainty of ±3 years (2σ). Extreme pIOD events lead to cooling of °C in 1961, 1963, 1967, 1994, 1997, and 2006 (red arrows). The sub-fossil core KNFa shows an extreme pIOD event on par with the event in 1997 in 1826 (black arrow). (b) Wavelet power spectra of SSTcenter time series of cores PB and KNFa. (c) Same as panel (b) but for core KN2. Power spectra of PB and KN2 are dominated by extreme pIOD events (red arrows in panel a). SSTcenter of KNFa shows enhanced seasonal variability between 1856 and 1918. Prior to 1856, seasonal variability is comparable to PB and KN2. Wavelet power spectra were computed in R using the Morlet wavelet. Thick black lines indicate significant periodicities at a certain time (p<0.05). Grey shading indicates the cone of influence.

The distribution of the measured data of KNFa is investigated in intervals representing approximately equal numbers of data points. The distribution is symmetric with a standard deviation of 0.05 to 0.053 mmol mol−1 in the upper sections of the coral core (slab 3 to the top of slab 8), symmetric with a standard deviation of 0.035 mmol mol−1 from slabs 8 to 9, and positively skewed with a standard deviation of 0.044 mmol mol−1 from slabs 10 to 11. Note, however, that the positive skewness of data from slabs 10 and 11 is due to only four consecutive data points of up to 9.148 mmol mol−1 on slab 11 (which cannot be attributed to diagenesis). The reduction in the standard deviation is due to a persistent change in the nature of the record that occurs ∼850 mm below the top of the coral (Fig. 5).

5.1 Sub-fossil coral data and diagenesis

Sub-fossil corals are an important archive to extend the instrumental record back into pre-industrial periods (Abram et al., 2020; Cobb et al., 2013; Sanchez et al., 2020). Living corals may grow continuously for more than 300 years (Zinke et al., 2004; DeLong et al., 2013; Linsley et al., 2000), but in many key regions of climate variability, extreme climate disturbances can contribute to their demise (Abram et al., 2003). However, applying the coral thermometer to sub-fossil corals is challenging as relatively minor amounts of diagenetic alteration can already significantly distort the thermometer (Allisson et al., 2007; Sayani et al., 2011, 2022). Standard screening protocols based on a destructive analysis of discrete samples by thin section, XRD, and SEM are not always sufficient to map out the often patchily distributed diagenetic phases in corals. In this study, only the diagenetic alteration at the top of the core was identified using conventional methods, while other patches of aragonite cements in slabs 5 to 7 were not detected. A way to circumvent this problem is through non-destructive methods that can be used to screen coral slabs for diagenetic phases at a high spatial resolution (Murphy et al., 2017). 2-D XRD analysis non-destructively quantifies the amount of calcite cement directly on the coral slab with a millimeter-scale spatial resolution (Smodej et al., 2015; Leupold et al., 2021). However, other types of diagenetic alteration such as aragonite dissolution or aragonite cements cannot be detected by XRD (Allison et al., 2007; McGregor and Abram, 2008). Typically, aragonite cements are patchily distributed (Nothdurft and Webb, 2009; Sayani et al., 2011, 2022; Smodej et al., 2015), while adjacent areas of the coral's skeleton are unaffected (Zinke et al., 2016). Such local concentrations of diagenetic phases could introduce spikes in the data or other proxy records that could be misinterpreted as climate events (Quinn and Taylor, 2006). Use of an SEM with an extra-large chamber, in combination with an ultra-variable-pressure detector (Fig. A5), allowed us to scan entire core slabs along the proxy sampling tracks without the need for a conductive coating. Our record showed an extreme spike with a ratio of 9.32 mmol mol−1 on transect 10 of slab 6 (Fig. 5). We were able attribute this extreme spike to a patch of aragonite cement and to omit this “false-alarm” spike from further interpretation. This is important as, at Enggano Island, such a spike would indicate an extreme pIOD event with a cooling exceeding −5 °C. Events of this magnitude do not occur in recent time periods captured in the satellite record, and including these data would have significantly impacted the climatic interpretation of core KNFa. Furthermore, the interval from the base of transect 9 to the top of transect 15 lacks clear seasonal variability in coral , which is normally indicative of irregularly distributed patches of diagenetic cements impacting the proxy, but since Enggano Island lies in a region with low seasonality, confirmation by SEM is important to map the extent of this zone. We conclude that it is important to clearly identify and delimit zones of even minor early marine diagenesis in young sub-fossil corals, preferably directly adjacent to the sampling transect of analysis, as a basis for a subsequent climatic interpretation of the data from sub-fossil corals (Sayani et al., 2022).

5.2 SSTcenter inferred from Enggano coral data since 1824

Two modern coral records (KN2 and PB) from Enggano Island were shown to closely track satellite SSTs that extend back to 1982 and to reliably record IOD variability, while gridded SST products interpolated from sparse historical data systematically underestimated extreme pIOD events – even in the time period covered by satellites (Yang et al., 2020; Pfeiffer et al., 2022). This has been attributed to non-linear ocean–atmosphere feedbacks in the south-eastern equatorial Indian Ocean that are not captured in the statistical methods used to interpolate historical SSTs from sparse observational data (Ng et al., 2015; Yang et al., 2020).

In this study, we re-evaluate the two single-core modern coral records as a basis for the interpretation of the sub-fossil KNFa record. We limit the interpretation of KNFa to aspects clearly seen in each single modern coral record. Figure A9 compares the coral records of the two modern corals from Enggano Island with the sub-fossil record of KNFa after interpolation to a monthly resolution. The most notable feature of the two modern coral records is the large positive anomalies during the extreme pIOD events of 1961, 1963, 1967, 1994, 1997, and 2006 (Figs. A9 and 6) (Pfeiffer et al., 2022).

Violin and box plots of the monthly data from each Enggano coral record are computed in time intervals spanning approximately 20 years (note that some variations arise from the total length of the time periods covered by the coral records). The median ratios of KN2 and PB are offset by mmol mol−1 (1σ) (Fig. A9), which would correspond to a difference > 1 °C when assuming a –SST relationship of −0.06 mmol mol−1 °C−1 (Corrège, 2006; Watanabe and Pfeiffer, 2022) if temperature-related. However, offsets in the mean or median coral ratios from different coral colonies are likely due to so-called “vital effects” (de Villiers et al., 1994; Watanabe and Pfeiffer, 2022; Ross et al., 2019) and have been seen even in coral records from adjacent colonies growing next to temperature loggers (Leupold et al., 2019). For climate reconstructions from corals, it is important that this offset remains constant within a coral core, which has been demonstrated in numerous calibration studies (Ross et al., 2019). The constant difference in median ratios between KN2 and PB supports the use of Enggano coral ratios as indicators of SST variability (Fig. A9).

Both modern coral cores show similar distributions of monthly data in each ∼20-year time interval, with a strong positive skewness in time periods with extreme pIOD events (1950–1969; 1990–2008) and a symmetric distribution in periods without extreme pIOD events (Fig. A9). This includes the number and spread of outliers (which reflect extreme pIOD events). The KNFa record, in contrast, shows symmetric distributions, although with a larger spread around the median (indicating a larger standard deviation of the data) in all time windows between 1856–1918. This is also seen in the raw un-interpolated data of KNFa (Fig. 5). Between 1824 and 1855, the spread of coral around the median reduces again to ranges seen in the modern cores, with outliers arising from a few extreme positive values in 1826, indicating an extreme pIOD event. The reduction in the standard deviation prior to 1856 is also seen in the raw un-interpolated data of core KNFa (Fig. 5).

Recent extreme pIOD events (1961, 1963, 1967, 1994, 1997, and 2006) in the SSTcenter records inferred from KN2 and PB data each indicate a cooling of °C at Enggano Island (Fig. 6; Pfeiffer et al., 2022). These extreme events also impacted the meridional SST gradient in the eastern equatorial Indian Ocean, with warm anomalies in the north and cold anomalies in the south, causing a northward shift in the southern boundary of the TCZ (Figs. 1 and A10). September–November mean SSTcenter data of KN2 and PB are highly correlated with the meridional SST gradient in the eastern Indian Ocean (Fig. A10).

The sub-fossil coral KNFa shows only one large anomaly in 1826, near the end of the coral record, which is on par with these recent extreme events (Fig. 6). SEM images confirm that the 1826 event cannot be attributed to diagenetic changes, and we therefore attribute it to an extreme pIOD event – the only one in the interval from 1824 to 1855 recorded at Enggano Island. Between 1856–1918, KNFa shows several cold anomalies in austral spring (Figs. 6 and A9), the largest of which (1882, 1886, 1890, 1908, and 1918) are comparable to 2006, with a slightly weaker extreme pIOD event in the modern record (Pfeiffer et al., 2022; Yang et al., 2020).

To better characterize the changes in SST variability inferred from coral over time, we computed wavelet power spectra. In the two modern records, extreme pIOD events are clearly seen as localized concentrations of power at sub-seasonal to interannual periodicities (Fig. 6). Seasonal variability is not persistent. This changes in the sub-fossil record of KNFa between 1856–1918. In this period, seasonal variability is a persistent signal, while interannual variability is not significant (Fig. 6). Prior to 1856, seasonal variability is again not persistent, and the single extreme pIOD event in 1826 is seen as a localized concentration of power at sub-seasonal to interannual periodicities (Fig. 6). These results suggest changes in the SST variability in the SE Indian Ocean that include changes in seasonality in addition to interannual variability associated with the IOD.

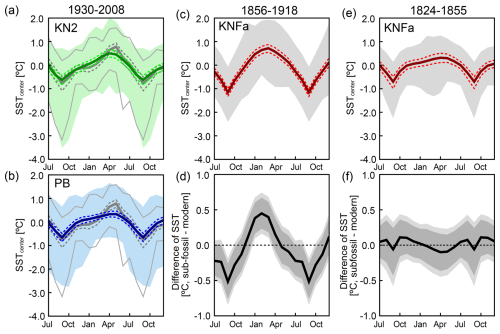

Figure 7Mean seasonal cycles of SSTcenter derived from modern and sub-fossil Enggano corals. (a) 1930–2008 from core KN2 (in green; solid line is monthly mean, dashed green lines are ±1σ, and green shading indicates 99 % percentiles of monthly means). Satellite SST data (Huang et al., 2021) (mean removed; thick grey line is monthly mean, and dashed grey lines are ±1σ; thin grey lines are 99 % percentiles of monthly means) are shown for comparison. (b) Same as panel (a) but for core PB (in blue; solid line is monthly mean, dashed blue lines are ±1σ, and blue shading indicates 99 % percentiles of monthly means). (c) Same as panel (a) but for core KNFa in the time period from 1856–1918 (in red; solid line is monthly mean, dashed red lines are ±1σ, and grey shading indicates 99 % percentiles of monthly means). (d) Difference of mean seasonal cycles: (1930–2008 monthly average data of KN2 and PB) minus (1856–1918 of monthly average data of KNFa), with 95 % and 99 % confidence levels (dark and light shading, respectively), based on a 20 000-sample Monte Carlo. Note the inflated y axis. (e, f) Same as panels (c) and (d) for the time period from 1824–1855 (KNFa).

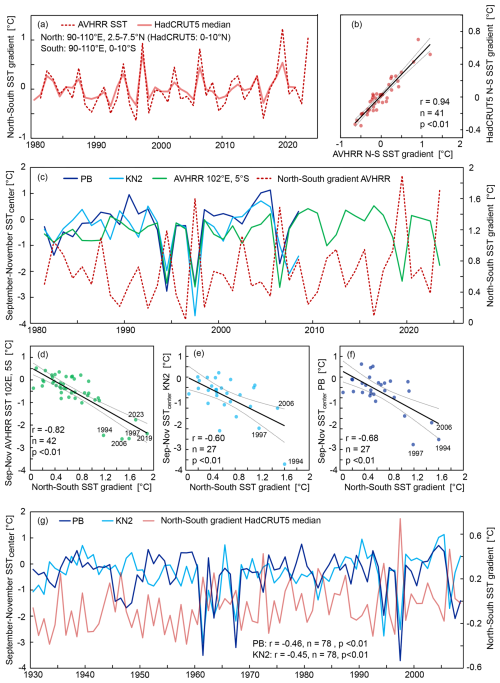

5.3 SST seasonality between 1856 and 1918

The wavelet power spectra (Fig. 6) of the sub-fossil coral show persistent SST seasonality between 1856 and 1918, while the modern corals (and the sub-fossil coral prior to 1856) show localized concentrations of power during extreme pIOD events. To further investigate these changes, we computed mean seasonal cycles of SSTcenter and their 99 % confidence intervals for the time periods from 1930–2008 (KN2 and PB), 1856–1918 (KNFa), and 1824–1855 (KNFa) (Fig. 7). Modern SSTcenter seasonality inferred from coral varies from 1.1 °C (KN2) to 1 °C (PB) between 1930 and 2008, consistent with satellite data of SST available since 1982 (Fig. 7). SSTcenter seasonality increases to ∼1.9 °C between 1856–1918 and then decreases again to modern values (∼1 °C) between 1824 and 1855. The difference in the mean seasonal cycles between 1930–2008 and 1856–1918 is statistically significant at the 99 % confidence level, while the mean seasonal cycles between 1930–2008 and 1824–1855 are statistically indistinguishable (Fig. 7). In the two modern SSTcenter records from Enggano Island, the extreme pIOD events (1961, 1963, 1967, 1994, 1997, and 2006) cause a strong skewness (Figs. 8, A8, and A9). This skewness is reflected in the 99 % confidence intervals around the September–November mean SSTcenter in Fig. 7 and is also seen in present-day satellite SSTs centered at Enggano Island (Fig. 3).

Figure 8(a–c) Distribution of September–November monthly mean SSTcenter inferred from the Enggano records (in blue) compared to satellite SSTs (in red; OI SST; ° grid; 1982–2008; centered to its mean) (Huang et al., 2021). Thick grey lines are the kernel density functions of the histograms. (a, b) Modern September–November SSTcenter (KN2 and PB) from 1960–2008 shows the same distribution as SSTs in the grid centered at Enggano Island. The negative skewness reflects the occurrence of extreme pIOD events. Between 1856–1918, September–November SSTcenter (KNFa) shows a symmetric distribution comparable to the SST distribution seen today at 7° S. (d) Percentiles of SSTcenter shown in panels (a)–(c). See Tables A3 and A4 for a comparison of the distributions using a Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Histograms and percentiles were computed using PAST (Hammer et al., 2001).

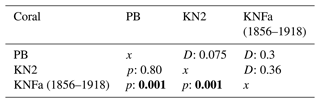

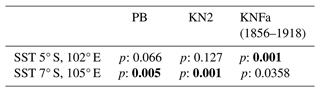

In contrast, in the time period from 1856–1918, when SSTcenter seasonality is enhanced, the distribution of September–November SSTcenter is symmetric (Figs. 7 and 8) and significantly differs from the modern data (based on a Kolmogorov–Smirnov test; see Table A3). In this period, strong September–November cooling occurs in almost every year (Fig. 6). The magnitude of the mean seasonal SSTcenter cycle and the distribution of September–November SSTcenter are comparable to satellite SSTs seen today at ∼7° S, i.e., off northern Java (Fig. 8; Table A4). Furthermore, maximum SSTs occur 1–2 months earlier than in modern coral SSTcenter and satellite SSTs, suggesting an early onset of austral spring cooling. Our results suggest stronger SE winds extending further to the north-west along the Java–Sumatra coast and an expansion of the region with strong wind- and upwelling-induced cooling in austral spring. We therefore believe that the increase in the seasonal cycle of SSTcenter between 1856–1918 reflects an earlier onset coupled with an increased strength of the SE winds in July–October, which then penetrated further north along the Java–Sumatra coast in almost every year and led to stronger cooling at Enggano Island. This would imply a shift in the mean position of the southern boundary of the TCZ to the north of Enggano Island in austral spring and a northward contraction of the eastern Indian Ocean Warm Pool coupled with a stronger meridional SST gradient (Weller and Cai, 2014; Weller et al., 2014). We favor this interpretation over a change in zonal variability associated with the IOD, as the IOD is by definition an interannual phenomenon of climate variability. At present, pIODs are relatively rare, impacting the 99 % confidence levels around the September–November mean SSTs rather than the monthly mean values of September–November SSTs (i.e., the mean seasonal cycle itself). Seasonality in the eastern tropical Indian Ocean, including the onset of the SE winds of Java and Sumatra, is primarily driven by the Asian summer monsoon, and changes in the mean state of the monsoon may impact the latitudinal position of the southern boundary of the TCZ in austral spring (Figs. 1 and 2) (Weller et al., 2014). An analysis of the Australian–Asian monsoon using 43 years of ERA-40 data does show long-term trends in onset/retreat dates and duration in each of the two monsoon seasons (Zhang, 2010), suggesting that this scenario is plausible.

5.4 Meridional and zonal Indian Ocean SST gradients in historical data

In this section, we assess how changes in the meridional and zonal SST gradients across the tropical Indian Ocean may have contributed to the change in mean climate inferred from the Enggano corals. We first confirm that the corals from Enggano Island track meridional changes in the north–south temperature gradient in the eastern Indian Ocean using satellite data. Following Weller et al. (2014), the meridional temperature gradient is calculated as the difference between SST averaged over (2.5–7.5° N, 90–110° E) and (10° S–Equator, 90–110° E). This index correlates negatively with September–November SST at Enggano Island (satellite SST; 1982–2024) and coral SSTcenter in the period of overlap (1982–2008) (Fig. A10). The north–south SST gradient calculated from satellite SST correlates with the north–south temperature gradient calculated from HadCRUT5 (Morice et al., 2021), which extends back to historical periods with a resolution of 5×5° grids. HadCRUT5 blends SST and surface air temperatures but does not use spatial interpolation to fill data gaps (Morice et al., 2021), thus providing the best coverage of actual historical temperature data. Note that the northern box of HadCRUT5 is averaged from the Equator to 10° N due to the lower spatial resolution of the dataset and slightly underestimates the magnitude of interannual variability (Fig. A10). Between 1930 and 2008, September–November SSTcenter inferred from the modern Enggano corals correlates negatively with the meridional temperature gradient calculated from HadCRUT5 (Fig. A10).

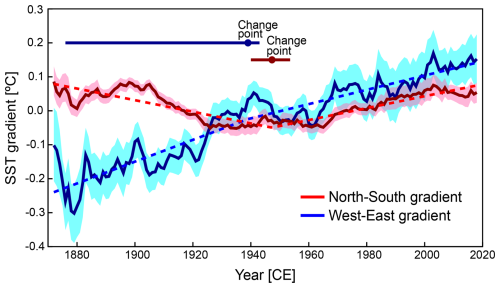

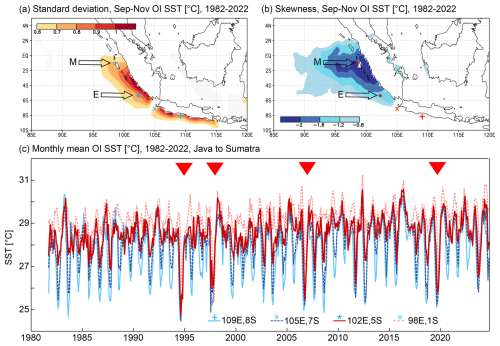

In the satellite era, interannual variations in meridional and zonal SST gradients across the tropical Indian Ocean are coupled; i.e., a northward contraction of the Indian Ocean Warm Pool is typically also associated with a reversal of the zonal SST gradient, resulting in a pIOD event (Weller and Cai, 2014). Only a few strong IOD events, such as the event of 1982, feature large zonal anomalies, while the southern boundary of the TCZ remains south of Enggano Island (Weller et al., 2014). To further assess this relationship on historical timescales, we have compared meridional and zonal temperature gradients across the tropical Indian Ocean using HadCRUT5 (Morice et al., 2021). Note, however, that these long-term temperature gradients may be affected by sparse observations in the Indian Ocean prior to the satellite era (Gopika et al., 2020). The zonal temperature gradient is calculated as the temperature difference between (10° N–10° S, 50–70° E) and (10° S–Equator, 90–110° E). The zonal gradient shows a long-term increase reflecting the continuous warming of the western Indian Ocean, which appears to have started before the beginning of historical records (Fig. 9) (Roxy et al., 2014; Gopika et al., 2020; Pfeiffer et al., 2017) at rates exceeding eastern Indian Ocean warming (Gopika et al., 2020). In contrast, the meridional temperature gradient calculated from HadCRUT5 does not show a significant long-term trend. It reverses in sign and diverges from the zonal SST gradient prior to 1925, with a warmer north-eastern Indian Ocean relative to the south-eastern tropical Indian Ocean (Fig. 9). In this period, the meridional SST gradient may have even exceeded present-day values. Taken together, this suggests a south meridional temperature gradient in the east. Similar results (not shown) were obtained using GISS Surface Temperature Analysis data (GISTEMP v4; 250 km smoothing) (Lenssen et al., 2019). Thus, the positive linear relationship between meridional and zonal SST gradients seen in the satellite era (Weller and Cai, 2014) does not hold for historical periods. The positive north–south SST gradient prior to ∼1930 should have driven stronger SE winds off Java and Sumatra in austral spring, which may have shifted the mean position of the southern boundary of the TCZ to the north of Enggano Island in September–November, supporting our interpretation of the Enggano coral data.

Figure 9Temperature gradients in the tropical Indian Ocean. North–south (red; 90–110° E, 0–10° N minus 90–110° E, 10° S–Equator) and west–east (blue; 50–70° E, 10° N–10° S minus 90–110° E, 10° S–Equator) Indian Ocean temperature gradients using HadCRUT5 (Morice et al., 2021). Temperature gradients shown are smoothed using 21-year moving averages. Shades in pink and blue indicate the uncertainty (1σ) calculated using bootstrapping methods. The west–east Indian Ocean temperature gradient has increased steadily since 1880 (p<0.01, Mann–Kendall test) but possibly decelerated after 1939 (95 % confidence interval (CI); 1876–1943 CE; SiZer test (Chaudhuri and Marron, 1999); horizontal blue line with circle). The exact onset of the deceleration cannot be determined (note the large 95 % confidence levels of the SiZer test). The north–south Indian Ocean temperature gradient does not show a significant long-term trend (p>0.1; Mann–Kendall test) and reverses prior to 1947 (95 % CI; 1940–1953 CE; horizontal red line with circle).

5.5 Comparison with other proxy records from the SE tropical Indian Ocean

An annual mean warm pool SST reconstruction based on corals from various sites of the West Pacific Warm Pool and tree rings from Java extends back to the late 18th century (D'Arrigo et al., 2006). This reconstruction shows cooling prior the 1930s, which would be consistent with stronger SE trade winds and greater cooling seen at Enggano Island in austral spring. Warm intervals interrupted by short cold spells between 1815–1850 correspond to the section of “modern” SST seasonality that is seen in the Enggano record between 1824 and 1855.

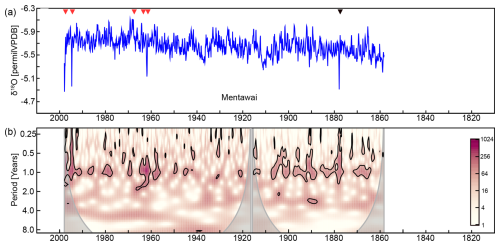

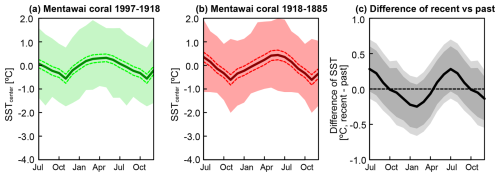

The first coral reconstruction of coastal upwelling associated with the IOD derives from a coral δ18O record from the northern Mentawai Islands, located approximately 4° further north of Enggano Island (Figs. 2, 3, A2, and A3) (Abram et al., 2008). The record lies at the northern edge of the Sumatra upwelling zone and extends from 1858 to 1997 (Fig. 10); i.e., it overlaps with the two modern Enggano coral records and the upper third of the sub-fossil coral KNFa. The northern Mentawai coral records the most extreme pIOD events in 1961, 1994, and 1997, when the boundary of the TCZ shifted far northwards, but not the events of 1963 and 1967 that are seen in the modern Enggano records (Fig. 10). Wind-induced coastal upwelling did not extend that far north during these events (Abram et al., 2015). The northern Mentawai record thus provides constraints on the northward shift in the southern boundary of the TCZ in austral spring. The northern Mentawai record does not show the increase in SST seasonality between 1856 and 1918 seen in the KNFa record (Figs. 10 and A11), which is attributed to a strengthening of the SE winds off Java and Sumatra in austral spring driven by the Asian monsoon. This would suggest that the boundary of the TCZ did not shift beyond the northern Mentawai Islands in this period. Prior to 1961, the northern Mentawai record shows one extreme pIOD event in 1877 that coincided with the very strong El Niño event of 1877/1878 (Abram et al., 2008). This event caused record drought and famine in much of Asia (Davis, 2002) and strong warming in the western tropical Indian Ocean (Pfeiffer and Dullo, 2006; Charles et al., 1997). The Mentawai record thus suggests that one extreme pIOD event occurred between 1856 and 1918 which was at least on par with the devastating event of 1997.

Figure 10Monthly coral δ18O record from northern Mentawai from Abram et al. (2008). (a) Monthly mean coral δ18O (thin blue lines) and 10-year running averages (thick red line) from 1858–1997. Red arrows mark extreme pIOD events seen in the record from Enggano (Pfeiffer et al., 2022). Note that the Mentawai coral record does not record the events of 1963 and 1967. One extreme pIOD event is recorded in 1877 (black arrow). (b) Wavelet power spectrum of the Mentawai record with largest variability in interannual periodicities. Wavelet power spectrum was computed in R using the Morlet wavelet. Thick black lines indicate significant periodicities at a certain time (p<0.05). Grey shading indicates the cone of influence.

Note that we do not see an extreme cold spike that can be attributed to the 1877 event in the KNFa record. We attribute this to the frequent upwelling seen in this record in the 1856–1918 period. Modern SST data may serve as an analogue to understand this phenomenon; during extreme pIOD events, such as 1997, upwelling cools September–November SSTs to <25 °C at all sites off the Java–Sumatra coast (Fig. A12). In other years, upwelling is spatially constrained to sites off Java, for example, at 7 and 8° S, where SSTs cool to ∼25 °C in many years (Fig. A12). The cooling during extreme pIOD events like 1994, 1997, 2006, or 2019 is therefore much smaller relative to the mean September–November SSTs. Between 1856–1918, SST variability inferred from the KNFa record is comparable to the SST variability seen today off Java at 7° S (Fig. 8; Table A4). This, combined with the age model uncertainty that derives from the UTh ages (Fig. A7), makes it difficult to unequivocally identify the 1877 event in the KNFa record. It could be reflected in one of the larger cold spikes seen ∼1880. Coral cores from various sites off the coast of Sumatra can therefore help to constrain the occurrence and magnitude of historical IOD events that pre-date the instrumental record. The Mentawai record suggests that the 1877 pIOD event was comparable to the 1997 event, while the KNFa record from Enggano suggests that this event occurred in a mean climate with stronger SE monsoon winds and a northward shift in the TCZ.

A reconstruction of the Indian Ocean Dipole Mode Index using a network of coral oxygen isotope records from the tropical Indian Ocean comprising the northern Mentawai record, Bali (Charles et al., 2003), and the Seychelles (Pfeiffer and Dullo, 2006; Charles et al., 1997) suggests that two additional pIOD events occurred between 1856 and 1918 (Abram et al., 2008, 2020). These events are not seen in the northern Mentawai record and may have been weaker than the 1877 event. Alternatively, they may have also been driven by warming in the western Indian Ocean, rather than cooling in the east (Jiang et al., 2022). Regardless of this, the low number of pIOD events between 1856–1918 would support the interpretation that the Enggano record shows a mean state change between 1856–1918 in response to an enhanced meridional SST gradient in the eastern Indian Ocean, rather than an increase in IOD frequency. This de-coupling between meridional and zonal variability has no analogue in the reliable instrumental record. However, future projections also suggest that meridional and zonal variability may de-couple, depending on the long-term evolution of the temperature gradients in the Indian Ocean (Weller et al., 2014).

New coral proxy data from South Pagai, which is part of the southern Mentawai Islands and lies approximately halfway between the northern Mentawai Islands and Enggano, could help to further constrain the relationship between meridional and zonal variability in the Indian Ocean. South Pagai is likely the best candidate for a stationary IOD teleconnection (Abram et al., 2015). A modern coral δ18O record from South Pagai extends back to 1959 and records all pIOD events seen in the modern Enggano record (Pfeiffer et al., 2022). Unfortunately, there is no record from South Pagai that overlaps with the Enggano data from 1856–1918. A sub-fossil coral δ18O record from South Pagai that extends from 1770–1820 shows six pIOD events in 50 years. This record pre-dates the 1824–1855 section of the Enggano record, where seasonality again compares with the modern Enggano corals of KN2 and PB.

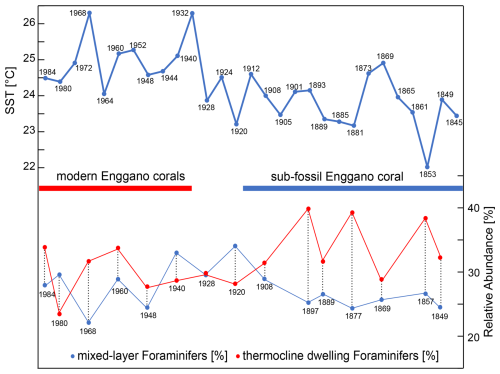

Figure 11Top panel shows mean SSTs inferred from foraminiferal ratios from a sediment core taken off Sumba island (Steinke et al., 2014a, b). Each dot represents one measurement, with estimated ages of Steinke et al. (2014b). Red (blue) horizontal bars indicate the time period covered by modern (sub-fossil) coral records from Enggano Island. Bottom panel shows relative abundance of mixed-layer (blue dots) and thermocline-dwelling (red dots) foraminifera (Steinke et al., 2014b). See the text for a discussion.

Another independent source of information on low-frequency climatic changes in the SE tropical Indian Ocean is provided by sediment cores. Their temporal resolution and age control are much lower when compared to sub-fossil coral records, but their record is more continuous and covers longer time periods. Steinke et al. (2014a, b) investigated a sediment core in the Timor Sea, north-west of Sumba island, spanning the last 2000 years (Fig. 11). Sumba island is located south-east of the main upwelling zone off the coast of Java (Fig. 2). In this region, moderate and extreme pIOD events cause anomalous cooling of SSTs (note that moderate pIODs tend to cause even stronger cooling than strong ones) (Fig. A3). A modern coral record from nearby Timor island (10° S, 123° E), which extends from 1914 to 2004, shows that decadal SST variability in this region tracks decadal IOD variability (Cahyarini et al., 2014). The top of the sediment core from Sumba island is dated to 1984±6 years CE (Steinke et al., 2014a) (Fig. 11). The record includes mixed-layer temperatures inferred from foraminiferal ratios with a temporal resolution of ∼5 years and relative abundances of mixed-layer and thermocline-dwelling foraminifera with a temporal resolution of ∼10 years (Fig. 11). Unfortunately, a turbidite limits the overlap with the Enggano record to 1845±9 years BP (Steinke et al., 2014a), which hampers a comparison with the shift back to modern SST seasonality between 1824 and 1855 seen in the coral record. Nevertheless, the sediment core data show a cooling of SSTs from a mean of 25.0 °C between 1932–1984 to a mean of 23.8 °C between 1845 and 1928; i.e., the difference exceeds −1 °C, which is statistically significant based on a two-sided Student t test (p<0.05). The inferred decrease in mean SST is accompanied by an increase in thermocline-dwelling foraminifera, while mixed-layer foraminifera abundance remained fairly constant (Fig. 11). This indicates that a shallowing of the thermocline in the SE tropical Indian Ocean prior to ∼1930, favoring the increased upwelling of cold water, was the most likely driver of the inferred cooling trend seen at Sumba island. Steinke et al. (2014b) linked this decrease in mean SST and thermocline depth to stronger SE trade winds in the SE tropical Indian Ocean, which is fully consistent with our interpretation of the Enggano record. Furthermore, Steinke et al. (2014b) suggest that these changes are part of a longer-term trend to cooler temperatures and a shallower thermocline during the Little Ice Age, despite some modulation by low-frequency variability. During the Medieval Warm Period, SE Indian Ocean SSTs warmed again, and the thermocline deepened, which should have reduced upwelling of cold water off Java and Sumatra (Steinke et al., 2014b). Interestingly, a 40-year sub-fossil coral record from Lampung Bay, located between Java and Sumatra, suggests reduced seasonal and interannual (IOD) variability during the Medieval Warm Period (Cahyarini et al., 2021), consistent with the record of Steinke et al. (2014b). Thus, the work of Steinke et al. (2014a, b) lends support to the changes in mean climate in the eastern equatorial Indian Ocean inferred from the Enggano record and suggests that it may be part of a centennial trend that extends beyond the time period covered by the instrumental and coral SST record from the SE tropical Indian Ocean.

The Enggano record reveals changes in SST seasonality in the SE tropical Indian Ocean on historical timescales. A period with enhanced seasonality occurs between 1856 and 1918 due to a cooling of mean September–November SSTs. This indicates an early onset of the Asian summer monsoon coupled with a northward expansion and strengthening of the SE winds off Java and Sumatra, qualitatively consistent with low-frequency centennial-scale changes inferred from high-resolution sediment core data (Steinke et al., 2014a, b). We attribute the enhanced seasonality to an enhanced meridional temperature gradient in the eastern tropical Indian Ocean, with warming in the north relative to the south, and a shift in the southern boundary of the TCZ to the north of 5° S in austral spring due to a stronger Asian summer monsoon. We note that the positive correlation between the meridional and the zonal SST gradient in the tropical Indian Ocean seen on interannual timescales does not hold for historical time periods. Between 1856 and 1918, the magnitude of the mean September–November cooling at Enggano Island is comparable to the cooling seen today during “weaker” extreme and moderate pIOD events. As even moderate IOD events may have significant climatic impacts in Indian Ocean rim countries, this warrants further investigation, especially since our data indicate quite abrupt transitions in seasonality on historical time periods. We conclude that meridional variability in the SE tropical Indian Ocean needs to be better understood. An array approach combining coral proxy data and high-resolution sediment core records along the coasts of Java and Sumatra would be ideal to better capture the full spectrum of climate variability in the SE tropical Indian Ocean.

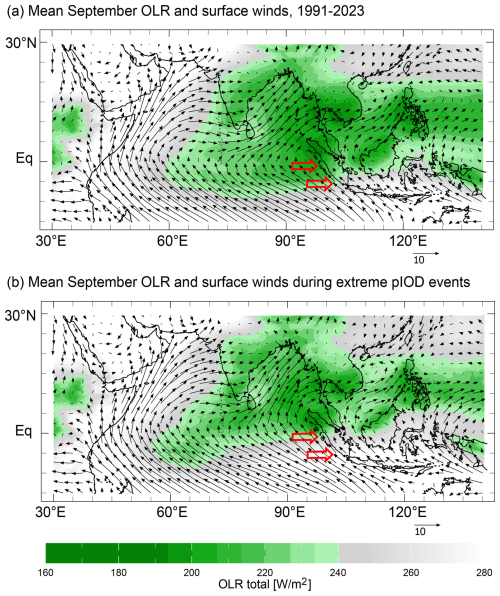

Figure A1Mean September outgoing longwave radiation (OLR; colors) (Schreck et al., 2018) and surface winds (vectors) (Kalnay et al., 1996) in the tropical Indian Ocean. (a) 1991–2023 average. (b) Composite of extreme pIOD events (1994, 1997, 2006, 2019, 2023). OLR ≤ 240 W m−2 (green shading) indicates the TCZ. Red arrows indicate the position of Enggano Island at 5° S and northern Mentawai at 1° S. Note that the boundary of the TCZ shifts to the north of Enggano Island during extreme pIOD events. Charts were computed at https://iridl.ldeo.columbia.edu/ (last access: 7 September 2024).

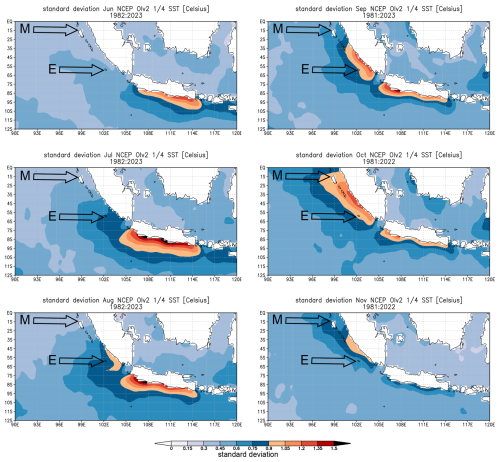

Figure A2Evolution of coastal upwelling off Java and Sumatra in austral spring (June–November) as expressed in the standard deviation of the monthly mean SST (colors). Coastal upwelling starts off Java in June, strengthens in July, and spreads to southern Sumatra in July/August. In September/October, upwelling reaches the Mentawai Islands located between 3° S and the Equator. Coastal upwelling subsides in November. Arrows mark the positions of Enggano (E) and Mentawai (M). Charts were computed at the KNMI Climate Explorer (https://climexp.knmi.nl, last access: 7 September 2024).

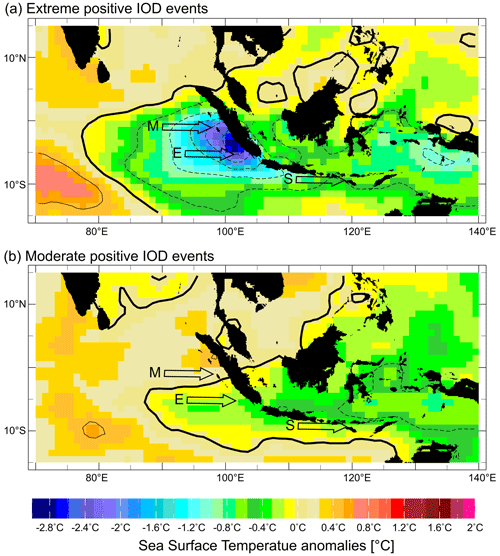

Figure A3Composite maps of September–November SST anomalies during (a) extreme pIOD events (1994, 1997, 2006, and 2019) and (b) moderate pIOD events (1982, 1983, 2012, and 2015). Arrows mark the positions of Enggano (E), Mentawai (M), and Sumba (S). Thick black lines mark zero contours, thin solid lines positive anomalies, and thin dashed lines negative anomalies at 0.5 °C steps. Data are from AVHRR OI SST (° grids; 1982–2022) (Huang et al., 2021). Charts were computed at https://iridl.ldeo.columbia.edu/ (last access: 7 September 2024).

Figure A4Luminescence scan of the sub-fossil coral core KNFa from Enggano. Core slabs are numbered. Note the dull and mottled appearance of the core top, which extends to the top of slab 2 and indicates potential secondary alteration. Parts of slab 6 look similar, although the effect is not as pronounced. These parts and adjacent transects were investigated using the Hitachi SU3900 SEM with an extra-large chamber. Slabs 10 and 11 show localized alterations which occur in areas affected by bio-erosion.

Figure A5Hitachi SU3900 SEM with an extra-large chamber. The sample holder has a diameter of 28 cm, which is shown here with slab 6 of core KNFa.

Figure A6SEM images showing pristine and diagenetic altered parts of sub-fossil coral KNFa. The top 14 cm of the core shows several macroscopic bio-erosion traces on X-ray images (Fig. 4). This interval (a, b) is characterized by filamentous microborings (MB), dissolution (D) of centers of calcification, and secondary aragonite (SA) cement. PST is the proxy sampling track. The degree of cementation is variable, ranging from (a) pristine coral skeletons and traces of cement to (b) more pervasive fibrous aragonite cement (5 to 10 µm length). The interval below 14 cm is generally pristine (c), showing smooth primary aragonite (PA) skeletal surfaces. The only exception occurs in an interval from the base of slab 5 to the top of slab 7 (d) (Fig. 5). A patch of secondary aragonite cement on transect 10 of slab 6 caused an extreme spike in the proxy record with unusually low ratio of 9.32 mmol mol−1. This “false-alarm” spike escaped detection by our first standard diagenetic screening but was identified by our semi-continuous SEM screening along the proxy sampling track.

Figure A7Corrected UTh ages of core KNFa with 2σ uncertainties vs. the number of years estimated from seasonal cycles in coral . The oldest year of KNFa is year 1. The age of the coral core was estimated from the intercept of the linear regression between the UTh ages and the annual cycles of (Fig. 5), assuming that the slope of this regression is 1 (i.e., assuming that the UTh ages agree with the number of annual cycles seen in coral ) (Domínguez-Villar et al., 2012). The base of KNFa is dated to 1824±3 (2σ) years CE. The floating age uncertainty was estimated with a Monte Carlo approach (20 000 loops) using the 2σ UTh error.

Figure A8Violin plots and box plots showing the distribution of monthly mean SSTs inferred from the modern Enggano corals (PB; KN2) compared with satellite SST (OI SST; ° grid) from 1982–2008 (Huang et al., 2021). Coral has been centered to its mean and converted to SST, assuming a –SST relationship of −0.06 mmol mol−1 1° C−1. Open circles (stars) indicate outliers exceeding ±1 (±1.5) standard deviations of the interquartile range. Violin plots are computed using PAST (Hammer et al., 2001).

Figure A9Modern and sub-fossil monthly interpolated coral time series from Enggano. (a) The complete Enggano record comprises two modern cores (PB and KN2) and one sub-fossil core (KNFa) and extends from 1930–2008, 1869–1918, and 1824–1862. Thin blue and green lines are monthly data, and thick solid and dashed red lines are 10-year running means. Note that the sub-fossil record has a floating chronology based on UTh dating with an age uncertainty of ±3 years (2σ). Relative changes in reflect temperature variations, with a mean –SST relationship of −0.06 mmol mol 1 °C−1 (Watanabe and Pfeiffer, 2022), which corresponds to one tick mark on the y axis. Positive anomalies in 2006, 1997, 1994, 1967, 1963, and 1961 indicate extreme pIOD events (red arrows). The sub-fossil record from KNFa indicates an extreme pIOD event in ∼1826 (black arrow). Events in 1908 and 1917 may be comparable with the comparatively weaker but still extreme pIOD of 2006. (b, c) Distribution of monthly coral data in ∼20-year bins is shown as violin plots and box plots. Values > 1 standard deviation (>1.5 standard deviations) above or below the 1.5 % interquartile range are plotted as open circles (stars). Outliers reflect extreme pIOD events. (b) Cores PB and KN2 from 1930–2008. The distributions are negatively skewed in 1990–2008 and 1950–1969 due to the occurrence of extreme pIOD events. Note the consistent shift in the medians of PB and KN2 data, indicating that vital effects remained stable over time. (c) Data from KNFa show a symmetric distribution between ∼1851–1918, with a larger spread around the median and few outliers. Between 1824 and 1850, the distribution is comparable to modern values. Violin plots are computed using PAST (Hammer et al., 2001).

Figure A10North–south temperature gradient in the tropical Indian Ocean from 1930–2023 and September–November SST at Enggano. (a, b) North–south temperature gradient in the eastern Indian Ocean calculated from satellite SST (AVHRR SST; ° grid; available since 1982) (Huang et al., 2021) compared with HadCRUT5 temperatures (Morice et al., 2021). (c) Mean September–November SST at Enggano (AVHRR) and SSTcenter inferred from KN2 and PB compared with the north–south SST gradient calculated from AVHRR. (d–f) Linear regression of September–November SST (AVHRR) at Enggano and SSTcenter from KN2 (e) and PB (d) with the north–south SST gradient (AVHRR). (g) Same as panel (c) but using the HadCRUT5 north–south temperature gradient. SST at Enggano correlates negatively with the meridional temperature gradient (colder SSTs at Enggano correspond to a stronger meridional gradient).

Figure A11Mean seasonal cycle of SST inferred from the from Mentawai coral δ18O record (Abram et al., 2008). (a) 1918–1997. (b) 1860 (end of record)–1918. (c) The difference between the mean seasonal cycles (thick black line) in panels (a) and (b) is not significant. The 95 % (dark grey) and 99 % confidence levels (light grey) overlap with the zero line. Significance was assessed with Monte Carlo as in Pfeiffer et al. (2022).

Figure A12Magnitude of seasonal cooling compared with IOD-induced upwelling along the coast of Java and Sumatra. (a) The standard deviation of September–November SST indicates areas of coastal upwelling off the coast of Java and Sumatra. (b) The skewness of September–November SSTs reflects coastal upwelling associated with pIOD events, which reaches Sumatra. Arrows in panels (a) and (b) mark the location of Enggano Island (E) and northern Mentawai Island (M). Charts were computed at the KNMI Climate Explorer (https://climexp.knmi.nl, last access: 7 September 2024). (c) Monthly mean satellite SST (OI SST; ° grid) from 1982–2024 (Huang et al., 2021) off the coasts of Java and Sumatra. Symbols indicate centers of SST grids (a, b). Coastal upwelling cools SSTs to <25 °C at all sites, resulting in uniformly cool SSTs during extreme positive IOD events (red arrows) when upwelling reaches the northern Mentawai Islands, for example, in 1997. In other years, coastal upwelling and cooling is spatially restricted to sites south of 7° S, making it harder to identify extreme pIOD events there. The intensity of pIOD events therefore mainly impacts/is seen in the northward extend of the cold anomalies off Sumatra.

Table A2Uranium and thorium isotopic compositions and ages of coral core KNFa by a multi-collector inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometer (MC-ICP-MS), Thermo Electron Neptune, at the National Taiwan University.

a for marine samples (Hiess et al., 2012); . b δ234Uinitial corrected was calculated based on 230Th age (T), i.e., , and T is corrected age. c , where T is the age. Decay constants used for age calculation are available in Cheng et al. (2013). d Age corrections for samples were calculated using an estimated atomic ratio of (Chiang et al., 2023). e Chemistry was performed on 15 September 2013. f Chemistry on 2 July 2015. Analytical errors are 2σ of the mean.

Table A3Results of Kolmogorov–Smirnov test (two samples) comparing the distributions of monthly September, October, and November coral data. D is the distance between the empirical distribution functions. The null hypothesis that the samples are drawn from the same distribution is rejected if p<0.01 (bold values).

Table A4Results of Kolmogorov–Smirnov test (two samples) comparing the distributions of monthly September, October, and November satellite SSTs from 1982–2008 at 5 and 7° S (centered) with SSTcenter inferred from the corals. The null hypothesis that the samples are drawn from the same distribution is rejected if p<0.01 (bold values).

All methods needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Appendix. The will be archived at the paleoclimatology branch of NOAA's National Center for Environmental Information (NCEI) (https://www.ncei.noaa.gov/access/paleo-search/study/40661, Pfeiffer et al., 2025). The raw materials are stored at BRIN (Indonesia).

MP conceived the study and wrote the paper. HT measured and interpreted the data. LR assessed the preservation of the coral samples. TKW helped with statistical analysis. LR, TKW, SI, DGS, and SYC contributed to data analysis and interpretation. DGS supported the analysis. TKW, CCW, and CCS dated the samples and helped with the development of the age models. JZ and GJB developed the method of coral luminescence scanning and helped with the interpretation of the data. SYC selected the study area and led the fieldwork. All authors contributed to writing the paper.

The contact author has declared that none of the authors has any competing interests.

Publisher's note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims made in the text, published maps, institutional affiliations, or any other geographical representation in this paper. While Copernicus Publications makes every effort to include appropriate place names, the final responsibility lies with the authors.

We thank Karen Bremer for laboratory assistance and the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) for funding the projects 468545728, 468545267 (SPP 2299/project no. 441832482), 260218773, and 39931928. Sri Yudawati Cahyarini acknowledges support from the Indonesia Toray Science Foundation Research Grant 2007 and the Alexander von Humboldt Georg Forster Research Fellowship for Experienced Researchers (ref 3.5 – IDN – 1158893 – GF-E). Hideko Takayanagi and Tsuyoshi Watanabe have been supported by the program “Multiple approaches for understanding earth environmental changes using biogenetic carbonates” that is part of the Strategic Young Researcher Overseas Visits Program for Accelerating Brain Circulation, Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT), Japan. The authors acknowledge the Indonesia Government research permit no. 46/SIP/IV/FR/5/2022. UTh dating was supported by grants from the National Taiwan University (NTU) Core Consortiums Project (112L894202), Higher Education Sprout Project of the Ministry of Education (112L901001), and the National Science and Technology Council (111-2116-M-002-022-MY3).

This research has been supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG; project nos. 468545728, 468545267 – SPP 2299/project nos. 441832482, 260218773, and 39931928 to Miriam Pfeiffer). Support has been received from the Indonesia Toray Science Foundation Research Grant 2007 and Alexander von Humboldt Georg Forster Research Fellowship for Experienced Researchers (Ref 3.5 – IDN –1158893 – GF-E; to Sri Yudawati Cahyarini). Support has been received from “Multiple approaches for understanding earth environmental changes using biogenetic carbonates”, Strategic Young Researcher Overseas Visits Program for Accelerating Brain Circulation, Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT), Japan (to Tsuyoshi Watanabe and Hideko Takayanagi). Support has been received from the National Taiwan University (NTU) Core Consortiums Project (112L894202), Higher Education Sprout Project of the Ministry of Education (112L901001), and the National Science and Technology Council (111-2116-M-002-022-MY3) (U/Th dating; to Chung-Che Wu and Chuan-Chou Shen). We also received the Indonesia Government Research Permit No. 46/SIP/IV/FR/5/2022.

This paper was edited by Nerilie Abram and reviewed by three anonymous referees.

Abram, N. J., Gagan, M. K., McCulloch, M. T., Chappell, J., and Hantoro, W. S.: Coral reef death during the 1997 Indian Ocean Dipole linked to Indonesian wildfires, Science, 301, 952–955, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1083841, 2003.

Abram, N. J., Gagan, M. K., Liu, Z., Hantoro, W. S., McCulloch, M. T., and Suwargadi, B. W.: Seasonal characteristics of the Indian Ocean Dipole during the Holocene epoch, Nature, 445, 299–302, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature05477, 2007.

Abram, N. J., Gagan, M. K., Cole, J. E., Hantoro, W. S., and Mudelsee, M.: Recent intensification of tropical climate variability in the Indian Ocean, Nat. Geosci., 1, 849–853, https://doi.org/10.1038/ngeo357, 2008.

Abram, N. J., Dixon, B. C., Rosevear, M. G., Plunkett, B., Gagan, M. K., Hantoro, W. S., and Phipps, S. J.: Optimized coral reconstructions of the Indian Ocean Dipole: An assessment of location and length considerations, Paleoceanography, 30, 1391–1405, https://doi.org/10.1002/2015PA002810, 2015.

Abram, N. J., Wright, N. M., Ellis, B., Dixon, B. C., Wurtzel, J. B., England, M. H., Ummenhofer, C. C., Philibosian, B., Cahyarini, S. Y., Yu, T.-L., Shen, C.-C., Cheng, H., Edwards, R. L., and Heslop, D.: Coupling of Indo-Pacific climate variability over the last millennium, Nature, 579, 385–392, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-2084-4, 2020.

Allison, N., Finch, A. A., Webster, J. M., and Clague, D. A.: Palaeoenvironmental records from fossil corals: The effects of submarine diagenesis on temperature and climate estimates, Geochim. Cosmochim. Ac., 71, 4693–4703, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gca.2007.07.026, 2007.

Ashok, K., Guan, Z., and Yamagata, T.: Influence of the Indian Ocean Dipole on the Australian winter rainfall, Geophys. Res. Lett., 30, 1821, https://doi.org/10.1029/2003GL017926, 2003.

Behera, S. K., Luo, J.-J., Masson, S., Delecluse, P., Gualdi, S., Navarra, A., and Yamagata, T.: Paramount Impact of the Indian Ocean Dipole on the East African Short Rains: A CGCM Study, J. Climate, 18, 4514–4530, https://doi.org/10.1175/JCLI3541.1, 2005.

Cahyarini, S. Y., Pfeiffer, M., Dullo, W.-C., Zinke, J., Hetzinger, S., Kasper, S., Grove, C., and Garbe-Schönberg, D.: Comment on “A snapshot of climate variability at Tahiti at 9.5 ka using a fossil coral from IODP Expedition 310” by Kristine L. DeLong, Terrence M. Quinn, Chuan-Chou Shen, and Ke Lin, Geochem. Geoph. Geosy., 12, Q03012, https://doi.org/10.1029/2010GC003377, 2011.

Cahyarini, S. Y., Pfeiffer, M., Nurhati, I. S., Aldrian, E., Dullo, W.-C., and Hetzinger, S.: Twentieth century sea surface temperature and salinity variations at Timor inferred from paired coral δ18O and measurements, J. Geophys. Res.-Oceans, 119, 4593–4604, https://doi.org/10.1002/2013jc009594, 2014.