the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Climatic signatures in early modern European grain harvest yields

Fredrik Charpentier Ljungqvist

Bo Christiansen

Jan Esper

Heli Huhtamaa

Lotta Leijonhufvud

Christian Pfister

Andrea Seim

Martin Karl Skoglund

Peter Thejll

The association between climate variability and grain harvest yields has been an important component of food security and economy in European history. Yet, inter-regional comparisons of climate–yield relationships have been hampered by locally varying data types and the use of different statistical methods. Using a coherent statistical framework, considering the effects of diverse serial correlations on statistical significance, we assess the temperature and hydroclimate (precipitation and drought) signatures in grain harvest yields across varying environmental settings of early modern (ca. 1500–1800) Europe. An unprecedentedly large network of yield records from northern (Sweden), central (Switzerland), and southern (Spain) Europe are compared with a diverse set of seasonally and annually resolved palaeoclimate reconstructions. Considering the effects of different crop types and time series frequencies, we find within regions consistent climate–harvest yield associations characterized by a significant summer soil moisture signal in Sweden, winter temperature and precipitation signals in Switzerland, and spring and annual mean temperature signals in Spain. The regional-scale climate–harvest associations are weaker than the recently revealed climate signals in early modern grain prices but similar in strength to modern climate–harvest relationships at comparable spatial scales. This is a noteworthy finding considering the uncertainties inherent in both historical harvest and palaeoclimate data.

- Article

(5785 KB) - Full-text XML

- BibTeX

- EndNote

Agriculture has been, and still is, highly weather and climate dependent (Hoogenboom, 2000; Cantelaube and Terres, 2005; Wallach et al., 2006; White et al., 2018; Lecerf et al., 2019; Vogel et al., 2019; Heino et al., 2020). In pre-industrial Europe, when human livelihood mainly relied on grain production for calorie intake (Allen, 2000), climate variations – and associated changes in weather patterns – were of immense importance for society (Degroot et al., 2021; Pfister and Wanner, 2021; Ljungqvist et al., 2022; White et al., 2023). Stimulated by the want to place contemporary global warming impacts on agriculture into a long-term perspective, investigations of past climate–harvest yield relationships have attained an increasing interest during the past 2 decades (for a review, see Ljungqvist et al., 2021). However, much of this scholarship has focused on the consequences for food security and related societal impacts in cases of consecutive years of adverse climatic conditions for grain production (Pfister and Brázdil, 1999; Pfister, 2005; Campbell, 2016; D'Arrigo et al., 2020; Huhtamaa et al., 2022; Stoffel et al., 2022). Years and decades with cold springs and excessively wet summers were associated with unfavourable conditions for crop growth north of the Mediterranean region (Camenisch, 2015; White et al., 2018; Pfister and Wanner, 2021). Droughts could have severe negative impacts on grain harvest yields too (Esper et al., 2017; Brázdil et al., 2020; Skoglund, 2022; Związek et al., 2022; Torbenson et al., 2023), although their agricultural impacts were geographically heterogeneous (Wetter et al., 2014; Brázdil et al., 2019) as is still the case in Europe today (Beillouin et al., 2020). In general, droughts are more spatially restricted than temperature anomalies in Europe (Büntgen et al., 2010; Cook et al., 2015; Ljungqvist et al., 2019), and they are less likely than temperature anomalies to occur over consecutive years (Bunde et al., 2013; Franke et al., 2013; Esper et al., 2017).

Quantitative and semi-quantitative analyses to estimate the impact of climate variability on past grain harvests extend back to the beginning of the nineteenth century (Herschel, 1801), followed by studies by Brückner (1895), Beveridge (1921, 1922), Le Roy Ladurie (1967), Parry (1975, 1976, 1978), and Pfister (1979, 1984, 1988), among others. Despite a comprehensive body of scholarship, conducted across different disciplines, only a handful of studies have attempted to statistically quantify the effect of temperature and hydroclimate (i.e. wetness or dryness) on harvest yields of different grain types in early modern Europe. Recent advances in palaeoclimatology have facilitated this research (Ljungqvist et al., 2021), although large-scale studies or inter-regional comparisons remain rare. An exception is the study by Pei et al. (2016), who by aggregating the heterogeneous and mostly short series of yield ratio data from Slicher van Bath (1963) found an apparently regionally different recovery after the “climax” of the Little Ice Age ca. 1570–1710 (Wanner et al., 2022): yields increased well above their pre-1570 level in western Europe as opposed to eastern Europe. Those differences were due to socio-political and technological factors rather than climate (Ljungqvist et al., 2021). Most longitudinal studies have detected relatively weak, and over time unstable, climate–grain harvest relationships (Edvinsson et al., 2009; Trnka et al., 2016; Skoglund, 2022; Soens, 2022).

The difficulty in obtaining time series of harvest yields from early modern Europe (Sect 2.1) has resulted in the frequent use of grain prices as a substitute for actual harvest data. Significant effects of climate variability on grain prices at inter-annual timescales have long been established (see, e.g. Mauelshagen, 2010). However, the influence of climate variability on decadal and longer timescales remained contested until recently. This is, in large part, because price inflation (and deflation) needs to be removed from the price series, which consequently also removes long-term price changes. By applying spline filter techniques to emphasize common mid-frequency variability, Esper et al. (2017) and Ljungqvist et al. (2022) found strong negative grain price–temperature relationships (i.e. colder temperatures being associated with high prices and vice versa) across Europe, which are of episodic rather than periodic (cyclic) nature (Ljungqvist et al., 2022). These studies showed that temperature strongly influenced early modern European grain production, and thus food security, to a larger extent than previously established.

Existing studies of climate effects on historical grain yields have mainly focused on very cold periods, in particular those containing known episodes of famines (e.g. Camenisch et al., 2016; Collet, 2019; D'Arrigo et al., 2020; Huhtamaa et al., 2022), or on extreme droughts (e.g. Brázdil et al., 2019) or floods (e.g. Kiss, 2019). However, a number of studies have also investigated the relationship between climate variability and grain yields over longer time periods (e.g. Landsteiner, 2005; Pfister, 2005; Edvinsson et al., 2009; Campbell, 2010, 2016; Huhtamaa et al., 2015; Huhtamaa and Helama, 2017; Skoglund, 2022; Martin et al., 2023). These studies have broadly shown that in northern Europe, at locations close to the thermal limits for grain agriculture, growing season length and temperature determine grain yields (for a review, see Ljungqvist et al., 2021). However, in the main agricultural areas of southeastern and southern Sweden, spring and summer hydroclimate conditions were the most important climate drivers of grain yields. More specifically, maximum harvest yields were obtained after warm winters and springs followed by cool and relatively moist summers (Edvinsson et al., 2009; Holopainen et al., 2012; Ljungqvist and Huhtamaa, 2021; Skoglund, 2022).

In central Europe, including Switzerland, cold spring periods during March–April and excessive summer precipitation lowered the grain harvest (Pfister, 2005), while moist conditions during September reduced the sown acreage and resulted in washed-out soil nitrogen (Pfister, 2007). In particular, for autumn-sown rye, wet autumns and winters had adverse effects on the next season's yields (Pfister, 1988) and on seed quality (Landsteiner, 2005). Drought had locally varying impacts on grain yields in this region (Wetter et al., 2014; Brázdil et al., 2019). Most importantly, clusters of rainy autumns, cold springs, and wet mid-summers could lead to multiple consecutive harvest failures and threatened food security across large regions of central Europe (White et al., 2018; Pfister and Wanner, 2021). Similar climatic signatures in the grain harvests, but with an even larger sensitivity to wet summer conditions, have been identified in maritime regions of western Europe, including England, where high July–August temperatures also tended to increase yields (Scott et al., 1998; Michaelowa, 2001; Brunt, 2015; Campbell, 2016; Pribyl, 2017; Soens, 2022). In Switzerland, and central Europe in general, spelt, wheat, rye, and some oats were autumn-sown crops (in September and October), while all barley and some oats were spring-sown crops (in March and April depending on the altitude). The spring-sown crops were harvested during June, prior to the season of severe summer droughts, and autumn-sown crops were harvested from mid-July onwards, with the exact timing dependent on both altitude and year (Pfister, 1984).

Due to the complex topography and diverse local-scale climatic conditions, the Mediterranean, including Spain, exhibits a highly variable climate between regions (Rodrigo and Barriendos, 2008; Santiago-Caballero, 2013b; Beck et al., 2018; Llopis et al., 2018, 2020). Many drought-prone regions were historically characterized by low average yields (Santiago-Caballero, 2013a). While spring droughts were generally the dominant climatic threat (Barriendos, 2005; Llopis et al., 2020), adverse effects might also arise from cold winters and/or springs (Moreda, 2017; Izdebski et al., 2018; Moreno et al., 2020). Autumn precipitation could have an effect on harvest yields as it provided soil moisture for the subsequent growing season. Wheat was the main crop in early modern Spain, sown in October to November, harvested in June in the south and July in the north, and mainly cultivated in the basins of major rivers (Moreno et al., 2020). Because of the warm climate and regular summer droughts, the main grain growing season in Spain extended from November to May, rendering summer climate conditions largely irrelevant for grain crops (Simpson, 1996; Mørch, 1999).

Similar to what has been found for historical times, only relatively weak climate–harvest yield relationships are reported for twentieth and twenty-first century European climate–harvest relationships. For example, Trnka et al. (2016) demonstrated rather weak climate–yield relationships for barley and wheat across most of Europe during the 1901–2012 period. While barley showed often insignificant relationships to monthly or seasonal temperature and precipitation variability, wheat showed stronger relationships. The explained variance from a combination of climate variables over the April–June season exceeded 25 % for wheat for Belgium, Bulgaria, Lower Saxony (Germany), Sweden, and Tuscany (Italy), although it did not exceed 13 % on average for Europe (Trnka et al., 2016). Climatic impacts also explain only a limited proportion of the modern German year-to-year grain yield variability (Albers et al., 2017). For much of Europe, drought conditions during April–June have the greatest impact on crop yields as demonstrated for, e.g. Czechia (Hlavinka et al., 2009) and Belgium (Gobin, 2012). Beillouin et al. (2020) found stronger relationships, explaining on average 34 % of the harvest variations for a variety of crops across Europe, with 46 % and 15 %, respectively, of the variance in yields explained by climate variability in northern/western and southern Europe since the early twentieth century. However, the large-scale effects of the warming trend in recent decades on agricultural productivity in Europe have been small: for example, growing season temperature and precipitation changes between 1989 and 2009 only reduced the potential continent-wide wheat yields by ∼2.5 % (Moore and Lobell, 2015). The estimated impact on global total wheat yields is almost identical (Iizumi et al., 2018). A linear relationship between climate and harvests can only be expected within certain ranges (e.g. Yin et al., 1995; Dell et al., 2014; De Toro et al., 2015). For most crops and locations, both excessive cold or heat and wetness or dryness would have been detrimental, and hence the climate–harvest correlation is obscured by years with contradictory effects. In contemporary studies on harvest yields, it has been clearly demonstrated that a consideration of the full range of impacts of a given climate indicator exhibits non-linear relationships (Schlenker and Roberts, 2009; Beillouin et al., 2020). This obviously puts limitations on linear estimations of the harvest–climate relationships.

In this article, we evaluate the association between grain harvest yields and seasonal temperature and hydroclimate variations in northern, central, and southern Europe during the 1500–1800 period. We compare data from Sweden, Switzerland, and Spain – as well as from some other regions such as England and southern Germany – and analyse how the yields of different grain types were impacted by varying climatic conditions. The assessment of sites across a north–south transect, including diverse environmental settings, supports comparisons of regional temperature and hydroclimatic impacts on different grain species. This study is the first to systematically assess the strength of the climate signal, and its significance, in early modern (ca. 1500–1800) Swedish, Swiss, and Spanish harvest data using a range of climate reconstructions. We focus on Sweden, Switzerland, and Spain as numerous grain yield (ratio) series and tithe series are available from these countries for the early modern period and since these countries represent a north-to-south gradient in Europe. For Sweden, Switzerland, and Spain the harvest series come from major agricultural regions that can be considered representative of harvest conditions in the three countries, although we note a large environmental heterogeneity within them.

Considering previous work on modern and historical climate–harvest relationships, we hypothesize for Sweden that warm winters and springs, relatively cool summers, and moderately high precipitation in spring and early summer benefited grain yields, whereas cold and/or dry springs and summers limited yields. Grain yields in Switzerland are expected to benefit from dry autumns and winters, warm springs and dry mid-summers. For Spain, wet and warm winters and springs are expected to increase grain yields, whereas summer conditions are irrelevant to the grain harvest because of the early harvest date. Following Ljungqvist et al. (2022), we emphasize conservatively calculated significance levels using a phase-scrambling-based method to establish the climate–harvest relationships. Additionally, we test for causality, i.e. the directions between the influence of one variable on another (e.g. climate variability causes changes in harvest yields).

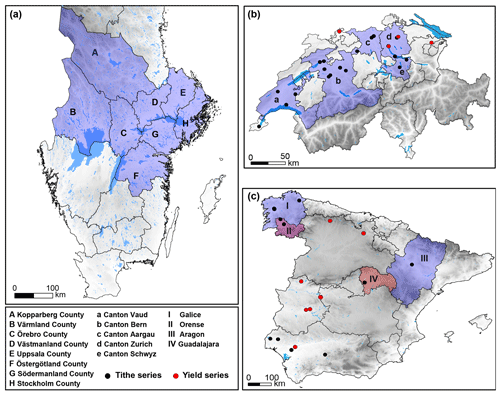

Figure 1Origin of grain tithe and yield data from (a) Sweden, (b) Switzerland, and (c) Spain. Note that for Sweden we use county-level average tithe data for barley/rye, oats, and wheat, and for Switzerland we use canton-level averages of all grain types, whereas the tithe data for Spain are derived from differently sized administrative districts. Tithe data aggregated at the provincial, canton or county level is shown in blue and yield data series in red. Due to their short length, and many data gaps, no yield series are used for Sweden.

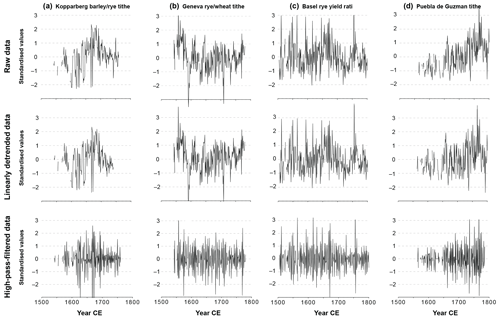

Figure 2Examples of harvest yield data from (a) Sweden (Kopparberg, barley/rye tithe), (b) Switzerland (Geneva, rye/wheat tithe), (c) Switzerland (Basel rye yield ratio), and (d) Spain (Puebla de Guzman tithe) for non-detrended (“raw”), linearly detrended, and 10-year Gaussian high-pass-filtered data. All the series shown have been standardized to zero mean and a standard deviation of 1. Note that the difference between non-detrended and linearly detrended is small in some series (e.g. Geneva) but relatively large in others (e.g. Puebla de Guzman).

2.1 Grain harvest data

Three main types of harvest data exist for the early modern period in Europe: (1) tithe records from areas where the tithe followed actual harvest size variations, (2) harvest yield ratio (i.e. sown-to-harvested grain) records from individual estates and farms, and (3) total yield quantity records for individual estates and farms or larger districts. Thus, tithe and total yield quantity records represent total grain production, whereas yield ratio records represent production relative to seed input. We have collected and digitized an unprecedentedly large dataset from published literature of both tithe and yield series of which only the longest (nearly) continuous ones have been included in this study (Tables 1 and 2). Whereas tithe data represent (sub)regional harvest variations, because the tithe data are recorded on the parish level, the yield data typically reflect local (estate)-scale yield variations. Tithe records, as they represent the output from numerous farms and usually cover a larger geographical area than yield series, can be expected to be less biased by individual outliers of single farms. The potential to study climate signals in early modern harvests using tithe data was already noted by Stauffer and Lüthi (1975). Continuous grain tithe data exist from parts of early modern Sweden, Switzerland, and Spain (Fig. 1; Table 1), as well as for some individual locations elsewhere across Europe not considered here. However, yield series (for example from one farm) may not even be locally representative. The effect of local soil conditions will be considerable, and microclimate and local weather events (e.g. one severe thunderstorm or local radiation night frost) will affect the yield ratio as well as the total yield quantity.

The lag-1 auto-correlation is much stronger in the tithe data compared to the yield data (mean AR1 =0.59 vs. 0.27) (Tables 1 and 2), indicating that the tithe time series contain a much larger “memory” from 1 year to the next. This pattern holds true for all study regions, albeit with large variations between individual tithe and yield series within each region. The auto-correlative structure of harvest series could be dependent on a number of factors, e.g. informal regulations of local tithes (Leijonhufvud, 2001), inadequate documentation (Le Roy Ladurie and Goy, 1982), or access to and shortage of seed grain (Huhtamaa et al., 2022). In comparison, grain price data contain an even stronger auto-correlation (mean AR1 = 0.78) than tithe data (Table A1), presumably due to the effects of storage, trade, and price regulations (Rahlf, 1996; Persson, 1999; Alfani and Ó Gráda, 2017). Temperature and hydroclimate reconstructions from documentary data contain auto-correlations similar to yield data, whereas tree-ring-based climate reconstructions instead contain auto-correlations similar to tithe data (Table 3; see Sect. 4.1).

For Sweden, the tithe data are only used from 1572 as the data from that year onwards were obtained through modern archival research (Myrdal and Söderberg, 1991; Leijonhufvud, 2001; Hallberg et al., 2016), whereas data prior to 1572 were compiled by Leijonhufvud (2001) from the publication by Forssell (1872), whose criteria and methods for collection remain uncertain. We merged the Swedish tithe data for barley and rye into a single “barley/rye” category as the two grain types are frequently reported as just “grain” in the tithe accounts (Ågren, 1964). In principle, “grain” in the account series generally implied a 50–50 distribution between rye and barley (Jansson et al., 1993), though this proportion shifted in reality (Leijonhufvud, 2001). Owing to insufficient tithe data coverage in some counties, we truncated the end date of individual county-level averaged tithe series (i.e. Östergötland and Södermanland in 1680, Stockholm and Värmland in 1730, Uppsala and Västmanland in 1740, and Kopparberg in 1760). Reliable tithe data for Örebro County are restricted to 1665–1720. For this study, we have not included any of the tithe data series from northern Sweden, present-day Finland, or the former Danish and Norwegian provinces that became Swedish in the mid-seventeenth century. Tithe data from Skaraborg County were also excluded as they contain numerous missing values (Leijonhufvud, 2001) and that county has a more maritime climate than the other counties (Wastenson et al., 1995). For Switzerland, rye and wheat production for the Republic of Bern and four districts of the Republic of Zurich has been estimated back to ca. 1530 based on tithe data (Pfister, 1984). Between 1755 and 1797, aggregate tithe receipts represented 57 % of the estimated total grain harvest, of which spelt accounted for the majority (see Tables 26 and 27 in Pfister, 1984). The tithe series for Spain are more heterogeneous with respect to quality and spatial domain (Ponsot, 1969; Eiras Roel, 1982; Ciria, 2007). Much of the tithe data are not separated by grain type but reflect the total agricultural productivity of grain, wine, and often also vegetables (Le Roy Ladurie and Goy, 1982). Only longer and more continuous tithe series for mainland Spain have therefore been included (Table 1).

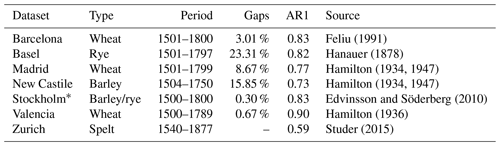

The majority of the published yield ratio series or area yield data series are short, frequently with numerous gaps (e.g. Slicher van Bath, 1963; Tornberg, 1989; Leijonhufvud, 2001; Young, 2007). Such yield ratio series are not included in this study as they complicate assessments of statistical significance in climate–harvest yield relationships. Yield data, sufficient in length for performing correlation analyses against (palaeo)climate data, exist for Switzerland and Spain (although only for the eighteenth century in the latter case) and for some individual locations elsewhere in Europe (Table 2). Both tithe data and yield data are henceforth referred to as “grain harvest data” or just “harvest data”.

Besides the gaps in the different harvest series, there are some other notable limitations. Some of the Swedish tithe data for different counties partly cover different periods (Leijonhufvud, 2001; Hallberg et al., 2016). These periods had somewhat different prevailing climate conditions (Luterbacher et al., 2004; Xoplaki et al., 2005; Leijonhufvud et al., 2010; Cook et al., 2015; Seftigen et al., 2017; Ljungqvist et al., 2019). Another important uncertainty regarding Swedish tithe data is the unknown variation in the number of farms paying tithes (equalling gaps in the sources) and the fact that the proportion of tithes to actual harvest may have decreased over time (Leijonhufvud, 2001). Over the decades, the practices may have become more standardized as Hegardt (1975) showed to be the case for the tithes collected for Uppsala University. In some areas, tithes were fixed at an average amount (Le Roy Ladurie and Goy, 1982), but those data are not included in this study. For Switzerland, uncertainty in estimating the actual harvest size is related to the fact that tithes were sold at auctions rather than collected in the field (Pfister, 1979). The Spanish tithe data are representing a mixture of tithes paid in grain and in money (Kain, 1979) and are mainly derived from rented land and therefore do not fully represent annual grain production (Llopis et al., 2020). Finally, many, though not all, of the tithe series consist of a mixture of different grains where the exact proportion was subject to changes over time (Le Roy Ladurie and Goy, 1982), which can make it more difficult to detect climatic signals since different grains can have different phenological requirements.

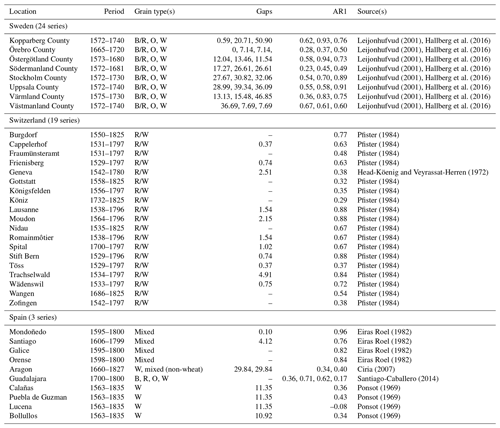

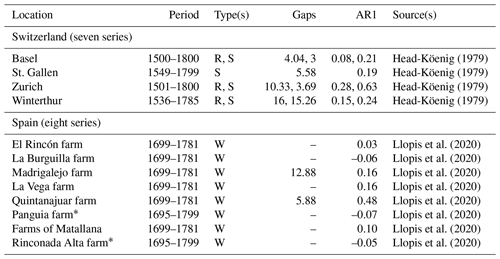

Leijonhufvud (2001)Hallberg et al. (2016)Leijonhufvud (2001)Hallberg et al. (2016)Leijonhufvud (2001)Hallberg et al. (2016)Leijonhufvud (2001)Hallberg et al. (2016)Leijonhufvud (2001)Hallberg et al. (2016)Leijonhufvud (2001)Hallberg et al. (2016)Leijonhufvud (2001)Hallberg et al. (2016)Leijonhufvud (2001)Hallberg et al. (2016)Pfister (1984)Pfister (1984)Pfister (1984)Pfister (1984)Head-Köenig and Veyrassat-Herren (1972)Pfister (1984)Pfister (1984)Pfister (1984)Pfister (1984)Pfister (1984)Pfister (1984)Pfister (1984)Pfister (1984)Pfister (1984)Pfister (1984)Pfister (1984)Pfister (1984)Pfister (1984)Pfister (1984)Eiras Roel (1982)Eiras Roel (1982)Eiras Roel (1982)Eiras Roel (1982)Ciria (2007)Santiago-Caballero (2014)Ponsot (1969)Ponsot (1969)Ponsot (1969)Ponsot (1969)Table 1Information on the grain tithe data, including the covered period and missing values (“gaps” in percentage), the grain type(s) (B is barley, R is rye, O is oats, W is wheat, B/R is a barley–rye mixture, and R/W is a rye–wheat mixture), the auto-correlation coefficient for a lag of 1 year, AR1 (numbers are in the order of the listed grain types), and the data source(s).

Table 2Information on the grain yield series, including location or site, the covered period and missing values (“gaps” in percentage), the grain type(s) (B is barley, R is rye, O is oats, S is spelt, and W is wheat), the auto-correlation coefficient for a lag of 1 year, AR1 (numbers are in the order of the listed grain types), and the data source.

* Yield per unit area and not yield ratio.

2.2 Temperature and hydroclimate data

Instrumental measurements of temperature are available for portions of Europe from the early eighteenth century onward; however, the longest extend back to 1659, and they become increasingly common from the mid-eighteenth century onwards for precipitation (Jones, 2001; Briffa et al., 2009; Brönnimann et al., 2019). Prior to this instrumental period, indirect, “proxy”, climate information has to be derived from either historical documentary sources (e.g. Pfister and Wanner, 2021) or natural archives such as tree rings (e.g. Esper et al., 2016; Ljungqvist et al., 2020). Seasonally gridded reconstructed temperature data – for winter, spring, summer, and autumn – covering Europe are available since 1500 (Luterbacher et al., 2004; Xoplaki et al., 2005 – henceforth referred to as Luterbacher et al., 2004; Table 3). These gridded products combine instrumental measurements from the eighteenth century onwards with documentary and natural proxy data. We also use the summer (June–August) temperature data from Luterbacher et al. (2016), as updated by Ljungqvist et al. (2019), derived from quality-screened temperature-sensitive tree-ring data and historical documentary evidence for June–August from Dobrovolný et al. (2010) resolved at a 5∘ × 5∘ grid. For the Luterbacher et al. (2004) and Ljungqvist et al. (2019) reconstructions, the local grid cells for each study region have been extracted, averaged, and utilized for the correlation analyses. In addition, for Switzerland we use the documentary-based seasonally resolved temperature reconstruction of Dobrovolný et al. (2010), and for Sweden we use the documentary-based January–April temperature reconstruction of Leijonhufvud et al. (2010). The Pfister (1992) and the Dobrovolný et al. (2010) reconstructions include some harvest-related proxy data for certain seasons and periods, an important limitation to note since it implies that they are not fully independent in relation to some of the harvest yield data employed here. Furthermore, they may contain deficiencies in the low-frequency domain, as documentary-based climate reconstructions based on the so-called index method are typically unable to capture the full amplitude of low-frequency climate variations (Adamson et al., 2022). A reconstruction of gridded seasonal precipitation estimates is available for the period after 1500 for Europe (Pauling et al., 2006). These data, as well as the Luterbacher et al. (2004) seasonal temperature field reconstruction, have some important limitations. Both seasonal field reconstructions have decreasing skill going back in time, especially prior to the early eighteenth century. They also lack local input data from Sweden during the period covered by the Swedish tithe series (see Table 1). Additionally, the climate models used to derive field reconstructions from the sparse data coverage in these two field reconstructions are out of date.

As an approximation of growing season soil moisture (drought) conditions we use the Old World Drought Atlas (Cook et al., 2015). This tree-ring-based reconstruction provides June–August soil moisture conditions as self-calibrated Palmer Drought Severity Index (scPDSI) values on a 0.5∘ × 0.5∘ grid across Europe. The atlas has limited skill in northern (Ljungqvist et al., 2019) and eastern (Cook et al., 2020) Europe; furthermore, it appears to somewhat underestimate the amplitude of low-frequency (multi-decadal to centennial scale) hydroclimatic variations at regional scales (compared with, e.g. Scharnweber et al., 2019; Büntgen et al., 2021). The local grid cells from the Pauling et al. (2006) and Cook et al. (2015) reconstructions for each study region have been extracted and utilized for the correlation analyses. For particular regions, additional non-gridded tree-ring-based hydroclimate reconstructions are used. This includes an annual groundwater level reconstruction from the Upper Rhine River Valley (Tegel et al., 2020); an April–August Standardized Precipitation–Evapotranspiration Index (SPEI) reconstruction from Bavaria, Germany (Muigg et al., 2020); and a June SPEI reconstruction from Scandinavia (Seftigen et al., 2017). For Switzerland, we used the Pfister (1992) indices, ranging from +3 (extremely warm, respectively wet) to −3 (extremely cold, respectively dry), derived from historical weather descriptions (Adamson et al., 2022). Index values of −1, 0, and 1 characterize rather average seasons derived from only narrative evidence, whereas values >1 and integrate both narrative and proxy evidence (for a further description of the Pfister indices, see Pfister and Wanner, 2021).

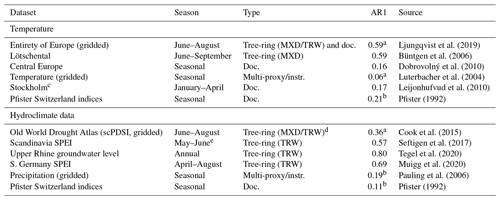

Ljungqvist et al. (2019)Büntgen et al. (2006)Dobrovolný et al. (2010)Luterbacher et al. (2004)Leijonhufvud et al. (2010)Pfister (1992)Cook et al. (2015)Seftigen et al. (2017)Tegel et al. (2020)Muigg et al. (2020)Pauling et al. (2006)Pfister (1992)Table 3Information on the palaeoclimate series, including the location, climate parameter, season, data type, the auto-correlation coefficient for a lag of 1 year, AR1, and data source. Abbreviations are as follows: Doc is documentary data, instr. is instrumental (meteorological) data, MXD is tree-ring maximum latewood density, and TRW is tree-ring width.

a Mean AR1 values of the area means of the different study regions. b Mean AR1 values of the different seasonal means. c Starts in 1502 with gaps in 1512–1516, 1519, 1523–1524, 1527, 1530–1532, and 1542. d Only 1 out of 106 predictors is maximum latewood density (MXD). The rest are tree-ring width (TRW). e June SPEI aggregated over a 2-month window, which corresponds to cumulative precipitation and evapotranspiration over May and June.

2.3 Detrending, correlation analysis, and significance

We detrended the harvest data because long-term yield trends are heavily influenced by factors related to human agency as opposed to climatic drivers (see Sect. 4.5). The following two different detrending methods are used: (1) linear detrending preserving variability on up to multi-decadal timescales and (2) 10-year high-pass Gaussian filtering preserving variability on only sub-decadal timescales (Fig. 2). All climate series have been detrended the same way as the harvest series. Linear detrending was performed by removing from the series an ordinary least-squares fit between the series and time. The linear fit is found by minimizing the mean square error. A possible issue with using linear detrending of early modern grain harvest data is the absence of a non-ambiguous long-term linear trend in some datasets. For example, in Sweden (Leijonhufvud, 2001; Hallberg et al., 2016) and in several regions of Switzerland (Pfister, 1984) it is difficult to discern any clear long-term productivity increases prior to the late eighteenth century. The trends in these series are often difference-stationary since there are stochastic shifts in the mean (Bauernfeind and Woitek, 1996). Tithe and yield series from some parts of Spain do appear to show long-term productivity gains earlier (Santiago-Caballero, 2013b), resulting in a larger effect on linear detrending (Fig. 2). While missing data are unproblematic for the linear detrending, they might affect the 10-year high-pass Gaussian filter. Before applying the filter, we therefore impute the missing values with a kernel smoothing method (Hastie et al., 2001). After applying the Gaussian filter, we restored the status of the missing values. We have also tested other detrending procedures as alternative to 10-year high-pass Gaussian filtering – e.g. first differencing – and find that the result is relatively robust to this choice. After detrending, we standardized the data to produce series with a mean of zero and standard deviation of 1. For calculating regional averages (e.g. all Swiss yield ratio series for rye), we lined the segments up according to time and then produced an aggregate series by averaging the values. We calculated no average for Spanish tithe or yield data given the complex topography and heterogeneous climatic conditions in Spain (Sect. 1).

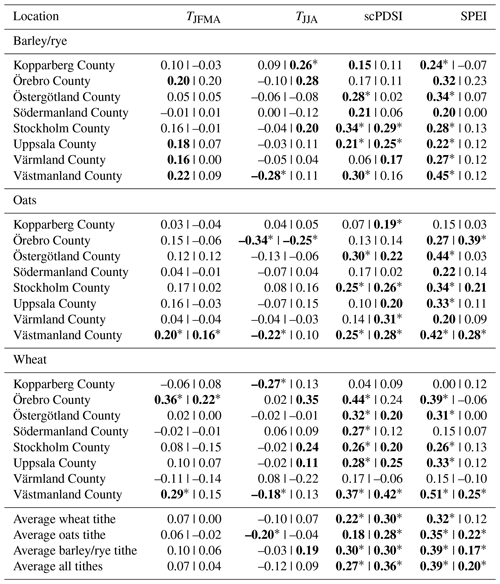

In this study, we quantify the association between the time series by the Pearson correlation coefficient (r). The finite length of the time series means that spurious correlations can appear. This problem is aggravated by the presence of considerable serial correlations in the time series, as evidenced by their rather large AR1 coefficients (see Tables 1–3). It is therefore important to report the statistical significance of correlations. The significance is calculated, as in Ljungqvist et al. (2022), both by the traditional method based on the Student's t statistics and by a phase-scrambling-based method. The latter method takes the actual number of degrees of freedom into account (Schreiber and Schmitz, 2000) and gives more accurate results when the time series contain serial correlations. This method is therefore more strict and reports fewer spurious significant correlations than the t test (Bartlett, 1935; Ljungqvist et al., 2022). Thus, we focus on results obtained with the conservative phase-scrambling-based significance test, although for comparison we also report significance obtained from the traditional t test.

It should be noted that in some cases we find weak and marginally significant correlations. However, if such correlations are found in several related pairs of time series – such as correlations between yields in neighbouring regions and different but related climate indices – the belief in a physical (non-spurious) connection is increased. Obtaining a formal significance level in this situation is difficult, instead here we adopt an informal manner, choosing to emphasize those results that individually are somewhat marginal but which taken together paint a consistent picture. Time-dependent variance in one or both of the time series (heteroskedasticity) can bias correlations because periods with a higher variance will dominate. In this study, such behaviour could originate in our use of climate series composed of both documentary or proxy and instrumental information. We find that this issue is not important in the present study as we have tested this by rescaling the variance in all series using 21-year running windows and found only negligible changes in correlations (not shown).

2.4 The Granger causality test procedure

For those pairs of series showing significant correlations, it is of interest to determine which of two correlated series is the cause of the variations in the other. We know that changes in some climate parameters have a readily detectable effect on grain harvests. Likewise, we also know that changes in harvest output had a substantial effect on the price of grain, but not the other way around (see, e.g. Rahlf, 1996; Persson, 1999; Barquín, 2005; Campbell and Ó Gráda, 2011). Confirming the right direction of causality gives an additional indication of the presence of a physical relationship. A formal causality test is the Granger causality test (Granger and Elliott, 1967; Granger, 1969; Reichel et al., 2001). The test considers significant correlations between series that are lagged relative to each other. A statistical causality is indicated if appropriately lagged series correlate while they do not at the opposite lag. While correlation is not causation, the Granger test provides hints for causality between pairs of series because statistical causation is a necessary, if not sufficient, condition for establishing a physical relationship.

In the procedure, two models are written – one for the series in terms of lagged values of itself and another that additionally includes lagged values of the other series. If the latter model is statistically better than the first one, we see that the inclusion of past values of the other series improves the explanatory power of the model with respect to the former simpler model. If we thereafter exchange the roles of the series and test again, we can by inspection understand whether their roles in explaining variance are symmetric or not. Only when the past values of one series help improve the prediction of another series – and not the other way around – have we found the presence of Granger causality.

Formally, we write

where subscripts indicate lags in variables; ϵ is the residuals or variance not explained by the model. Equations (1) and (2) are estimated, and a Wald hypothesis test (Diggle et al., 2002) is performed to see if Eq. (2) is superior to (1). If so, we have preliminary signs of causality from the x series to the y series. We test Eqs. (3) and (4) as well. If Eq. (4) does not have better explanatory power than Eq. (3), we then know that the inclusion of y is unable to improve the explanatory power of x and y; i.e. past values of x help explain present values of y – but not the other way around. The maximum number of lags used, m, must be chosen. For this article, we applied the Wald test at the p=0.05 significance level and allowed lags up to 3 years (m=3) as longer lags appear unmotivated in the study of climate–harvest (or harvest–price) relationships (see, e.g. Bekar, 2019; Huhtamaa et al., 2022; Ljungqvist et al., 2022). The Granger causality is calculated both on the 10-year high-pass-filtered data and on linearly detrended data. To evaluate the skill of the Granger causality test in assessing climate–harvest yield relationships, we also calculate Granger causality on harvest yields and grain prices, using a limited price dataset (Table A1), as the true direction of this relationship during this time period is without question (i.e. from harvests to prices).

The study of the correlation between series can be confounded by the presence of auto-correlative structure in the series (von Storch and Zwiers, 1999). Series correlation and its significance can be calculated between any level stationary series as long as the presence of autocorrelation in one or both series is taken into account by the inclusion of lagged terms in the model. These are the equation terms at lags t−1, t−2, etc., as seen above. In Sect. 3.4 we only report results of tests that are unambiguous; i.e. we consider only Granger causality tests where a clear causality direction is indicated and do not consider Granger test results where one or more of the tests involved were not significant.

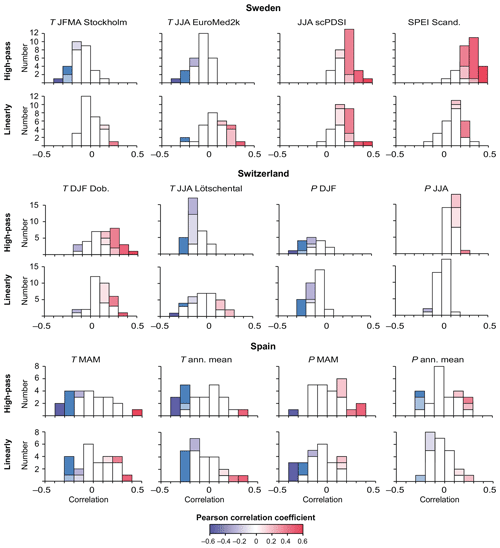

In the following three sub-sections, Sect. 3.1–3.3, we present the results for Sweden, Switzerland, and Spain, respectively. The climate–harvest correlations are shown in Figs. 3–5 for each country separately, while the distribution of the most important climate–harvest yield correlations are summarized in Fig. 6. Finally, we consider the Granger causality results in Sect. 3.4.

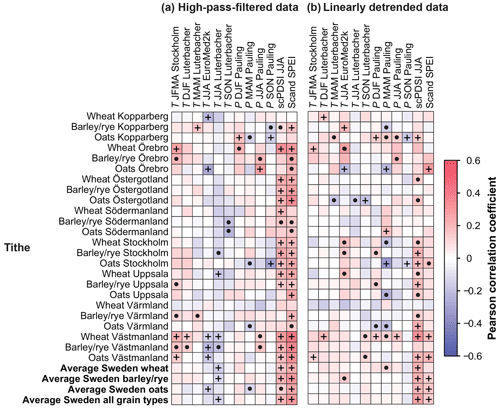

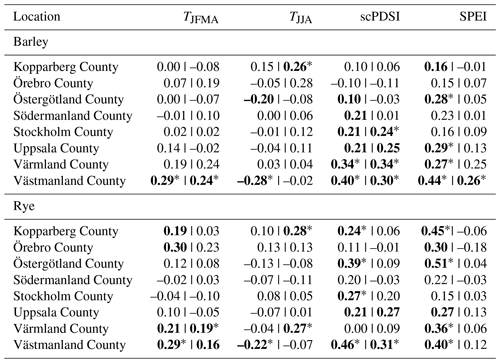

3.1 Climate–harvest yield relationships in Sweden

The strongest and most consistent climate signal recorded in the Swedish grain tithe series is the positive association with summer soil moisture (i.e. wetter conditions meaning higher yields and vice versa) (Fig. 3). This association is found both with 10-year high-pass-filtered data and the linearly detrended data. Focusing first on the results obtained using high-pass-filtered data, the relationship between harvest yields and soil moisture is significant in 57 % (phase-scrambling test) and 68 % (t test) of the cases for scPDSI and in 68 % (phase-scrambling test) and 86 % (t test) for SPEI. Notably, all tithe series averaged by type show significant positive correlations with soil moisture (Table A2).

Stronger correlations than in most county-level tithe series are obtained between the mean of the tithe series and SPEI and scPDSI with r=0.18 and 0.35 for oats, 0.32 and 0.22 for wheat, 0.39 and 0.30 for barley/rye, and 0.39 and 0.27, respectively, for the average of all the Swedish tithe series. Correlations exceeding r=0.40 against SPEI are found for all grain types in Västmanland County and for oats in Östergötland County. Weak and insignificant correlations are mainly found for the counties of Kopparberg and Värmland located in a wetter and cooler region (Table A2). The relationship with reconstructed precipitation is weak and mainly insignificant in all counties (see further discussion in Sect. 4.3).

Only a limited number of high-pass-filtered Swedish tithe series show a significant positive or negative relationship with temperature in any season. There is a minor tendency towards positive correlations between grain yields and Stockholm January–April temperature, though this association is only significant in 11 % (phase-scrambling test) and 25 % (t test) of the cases. Importantly, this relationship is insignificant with either test for the averaged tithe series. Almost all individual tithe series, and all the averaged tithe series, show a negative association with June–August temperature. Significant negative correlations are obtained in 21 % of the cases, with both significance tests using the EuroMed2k reconstruction, while 18 % (phase-scrambling test) and 25 % (t test) is reached for the Luterbacher et al. (2004) temperature reconstruction. However, importantly, all the averaged tithe series show significant negative correlations with a phase-scrambling-based significance test against at least one of the two June–August temperature reconstructions.

The relationship between grain tithes and summer soil moisture, especially SPEI, weakens when considering linearly detrended data, with mean correlations of r=0.19 and 0.12 with scPDSI and SPEI, respectively (compared to r=0.22 and 0.30, respectively, for high-pass-filtered data; Table A2). Winter temperature–harvest relationships are weaker (and mainly insignificant) in the linearly detrended data than in the high-pass-filtered data. We observe a shift from generally negative summer temperature–harvest correlations (i.e. cold temperatures meaning high yields and vice versa) in the high-pass-filtered data to weakly positive (i.e. warm temperatures meaning higher yields and vice versa), though mainly insignificant, summer temperature–harvest relationships in the linearly detrended data. Using the high-pass-filtered data, the tithe series reveal a negative summer temperature association in 75 % of the cases, while the linearly detrended tithe series instead showed a positive association – significant or not – in 71 % of the cases (Table A2).

Despite shorter time series we also tested the barley and rye tithes separately (Table A3), and found that correlations are, in general, less significant than for the combined barley/rye tithes. While the overall correlation pattern is similar to the pattern for the combined barley/rye data, some differences in the climate–harvest association can be noted between barley and rye. Rye shows, in general, a stronger positive correlation with summer soil moisture than barley considering high-pass-filtered data but not considering linearly detrended data. No significant winter temperature signal is found in barley, Västmanland County being an exception, while rye shows several significant positive correlations, in particular for high-pass-filtered data. Furthermore, we note that several of the Swedish tithe series, including the counties of Stockholm and Uppsala, have gaps and single years of “outliers” that have a large effect on the results. For example, for Uppsala County when considering only the 1690–1740 period using linearly detrended data, we found a positive correlation between summer temperature and barley (r=0.39), rye (r=0.44), and barley/rye (r=0.24) (not shown).

Figure 3Cross-correlation matrix for Sweden between climate series and grain tithe series at a county level for 10-year high-pass Gaussian filtered data (a) and linearly detrended data (b), respectively. Correlations significant at the p=0.05 level with a t test are marked with a dot (⋅). Values that are additionally significant using the phase-scrambling test are marked with a plus sign (+).

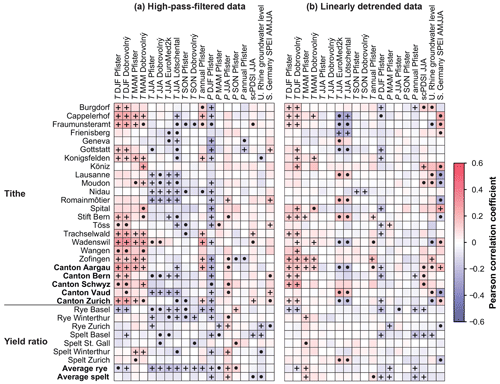

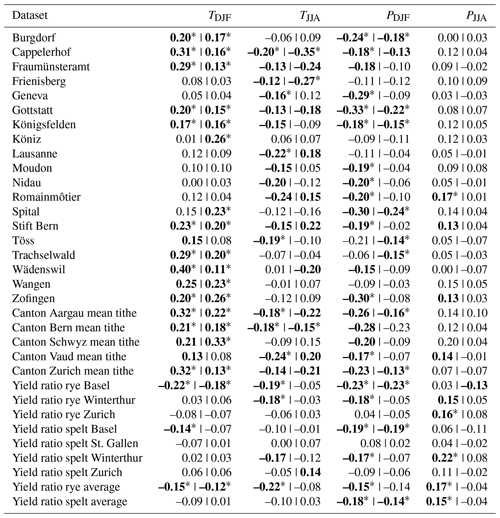

3.2 Climate–harvest yield relationships in Switzerland

The strongest and most consistent climate signal in harvest yields in Switzerland, when using 10-year high-pass-filtered data, is the negative relationship between harvests and December–February precipitation (i.e. higher precipitation meaning lower yields and vice versa) (Fig. 4). This association is significant in 70 % of the cases considering the phase-scrambling-based significance test (in 76 % with a t test). The mean correlation between December–February precipitation and the Swiss tithe series is , with a range from (Trachselwald) to (Gottstatt). Mean correlation for Swiss yield ratio data is , with a range from r=0.08 (St. Gallen spelt) to (Basel rye).

An almost equally strong climate signal, as with winter precipitation, in the high-pass-filtered data is the positive association between the tithe series and December–February temperature (i.e. higher temperatures meaning higher tithes and vice versa). The Pfister (1992) and Dobrovolný et al. (2010) reconstructions give almost identical results, with 50 % significant positive correlations for both datasets with the phase-scrambling-based significance test (63 % vs. 67 % significant with a t test). As opposed to the tithe records, the yield ratio records mostly show a negative – in some cases significant – correlation with December–February temperature. This negative association is most evident for the Basel rye yield ratio record and the averaged rye yield ratio record (Table A4). The mean correlation between reconstructed Pfister December–February temperature (alternatively the December–February reconstruction by Dobrovolný et al., 2010), shown within parentheses) and the Swiss tithe series is r=0.18 (0.19), with a range from (0.00) (Nidau) to r=0.37 (0.40) (Wadenswil). The corresponding correlation for Swiss yield ratio data is a mean of (−0.07), with a range from r=0.08 (0.06) (Zurich spelt) to (−0.22) (Basel rye).

Many of the Swiss tithe series also reveal a positive correlation with spring and, to a lesser extent, annual mean temperature (Fig. 4). Using the Pfister March–May temperature indices, 27 % of the harvest series show significant positive correlations with the phase-scrambling-based significance test (33 % with a t test), and 30 % (45 % with a t test) show the same pattern when using the March–May Dobrovolný et al. (2010) temperature reconstruction. Considering annual mean temperature, the Pfister temperature indices show positive significant correlations with 21 % of the harvest series with a phase-scrambling-based significance test (27 % with a t test). On the other hand, it also shows two cases of significantly negative correlations with a phase-scrambling-based significance test (three cases with a t test).

The strongest and most consistent negative Swiss harvest–summer temperature association in the high-pass-filtered data is found for the tree-ring maximum latewood density-based Lötschental summer temperature reconstruction. This association is significant in 36 % (phase-scrambling test) and 61 % (t test) of the cases. The averaged rye yield ratio for Switzerland shows a significant negative correlation with both temperature and precipitation during most seasons, except for significant positive correlations with summer and autumn precipitation, while the averaged spelt yield ratio only shows a significant negative correlation with winter precipitation and a significant positive one with summer precipitation (Fig. 4; Table A4).

In general, weaker correlations are found using linearly detrended data instead of high-pass-filtered data. However, stronger – but mixed – correlations are obtained with the linearly detrended data against reconstructed groundwater levels, scPDSI, and SPEI. The mainly positive association between winter temperature and harvests remains, albeit weakened, while it essentially disappears for spring temperature (Fig. 4). Likewise, the negative relationship between winter precipitation and harvests is retained in linearly detrended data but is considerably weaker and less significant than in high-pass-filtered data (Table A4). Furthermore, the already weak positive relationship between summer precipitation and harvests in high-pass-filtered data is entirely absent in the linearly detrended data.

Notably, when using linearly detrended data instead of high-pass-filtered data, almost all significant correlations between harvests and summer temperature disappear with the phase-scrambling test. Only three of them still remain significant with the less strict t test for the Lötschental summer temperature reconstruction (Fig. 4). Furthermore, while the relationship between Swiss harvests and summer temperature is consistently negative (i.e. colder temperatures meaning high yields and vice versa) when using high-pass-filtered data, more mixed signals are recorded when using linearly detrended data. Thus, the consistent negative relationship is restricted to the high-frequency domain, and a geographically more varied association prevails when information on longer timescales is retained (see the discussion in Sect. 4.1). In the distribution of correlations for Lötschental summer temperatures shown in Fig. 6, we see a distribution of correlations using linearly detrended data symmetric around zero as opposed to the mainly negative clustering of correlations using high-pass-filtered data. This implies the presence of an important signal at inter-annual timescales and a lack of any meaningful association over longer timescales. A similar result is seen for Swiss summer precipitation (Fig. 6).

Figure 4Cross-correlation matrix for Switzerland between climate series and grain tithe and yield ratio series for 10-year high-pass Gaussian filtered data (a) and linearly detrended data (b), respectively. Correlations significant at the p=0.05 level with a t test are marked with a dot (⋅). Values that are additionally significant using the phase-scrambling test are marked with a plus sign (+).

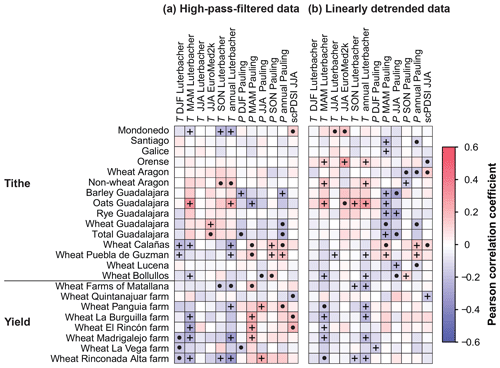

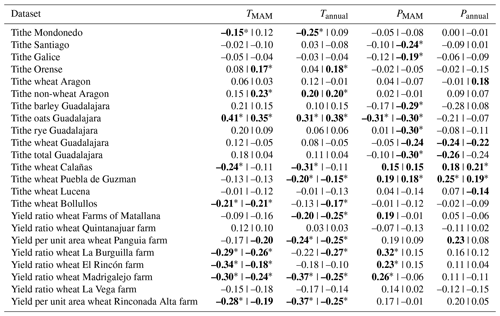

3.3 Climate–harvest yield relationships in Spain

No consistent climate–harvest relationship, for either temperature or hydroclimate, is found for Spain using either high-pass-filtered or linearly detrended data (Fig. 5). The most significant correlations for high-passed filtered data are obtained for the March–May season, the main Spanish grain growing period (Sect. 1), as well as for annual mean values of temperature and precipitation. Several series are negatively correlated with December–February temperatures (Table A5). The direction of the correlations varies between locations (but maintaining local consistency), although it is mostly negative for temperature and positive for precipitation. The tithe series from Aragon and Guadalajara exhibit a different climate signature than most other Spanish series. Non-wheat tithe data from Aragon show, with a t test, significant positive correlations with September–November temperature and with annual mean temperature. Oat tithe data from Guadalajara exhibit, also with a phase-scrambling-based significance test, significant positive temperature associations for March–May and the annual mean. The wheat tithe data from Guadalajara correlate significantly positively with June–August temperature with a phase-scrambling-based significance test, whereas the average of the Guadalajara tithe data of all grain types are significantly correlated but only with a t test. Furthermore, as opposed to most other Spanish harvest series, all Guadalajara tithe series show a negative – in some cases significantly so – relationship to precipitation during all seasons. All significant correlations, both for high-pass-filtered and linearly detrended data, between Spanish yield series for wheat and temperature are negative (i.e. warmer temperatures meaning lower yields and vice versa).

Comparatively similar correlation patterns and significance levels to those using high-pass-filtered data are obtained for Spain when using linearly detrended data – which is in contrast to the findings from Sweden and Switzerland (Sect. 3.1–3.2). In fact, we find no contradicting significant results between high-pass-filtered data and linearly detrended data. However, a more significant negative correlation between the Guadalajara tithe series (covering only the eighteenth century) and March–May precipitation appears when using linearly detrended data (Table A5). Likewise, the positive relationship between March–May precipitation and several of the yield series disappears. Furthermore, the association with December–February temperature is weakened.

Figure 5Cross-correlation matrix for Spain between climate series and grain tithe and yield ratio series for 10-year high-pass Gaussian filtered data (a) and linearly detrended data (b). Correlations significant at the p=0.05 level with a t test are marked with a dot (⋅). Values that are additionally significant using the phase-scrambling test are marked with a plus sign (+).

Figure 6Histograms showing the distribution of the most important climate–harvest yield correlations. Significant correlations are shown for the conservative phase-scrambling technique (dark-coloured bars) and for the standard parametric t test (light-coloured bars). The colour scheme follows the matrices in Figs. 3–5. Abbreviations are as follows: ann. mean is the annual mean, DJF is December–February, Dob. is Dobrovolný et al. (2010), JFMA is January–April, JJA is June–August, MAM is March–May, P is precipitation, scPDSI is Self-Calibrating Palmer Drought Severity Index, SPEI is Standardized Precipitation-Evapotranspiration Index, and T is temperature.

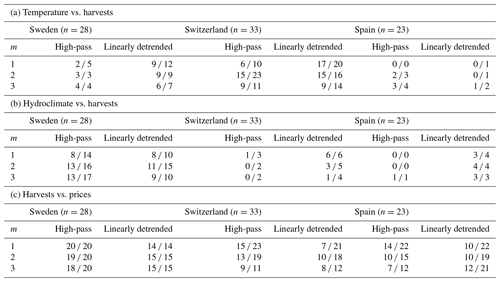

3.4 Granger causality of climate–harvest yield relationships

To establish the direction of causality, in order to reduce the possibility of spurious climate–harvest yield associations, we performed Granger causality analyses between harvest data and those temperature and hydroclimatic reconstructions with the most significant correlations for Sweden, Switzerland, and Spain (as listed in Tables A2–A5). This means EuroMed2k June–August temperature and Scandinavian SPEI for Sweden, Dobrovolný et al. (2010) December–February temperature and December–February precipitation for Switzerland, and March–May temperature and precipitation for Spain. In addition, we perform a Granger causality analysis between harvest series and regional grain price data (listed in Table A1) for the same three regions to investigate and preclude the possibility of spurious correlations.

In the case of Sweden, we have 28 harvest (tithe) series to be tested for temperature–harvest relationships of which only a handful provide evidence for a Granger causality relationship. We note that linearly detrended data give stronger results, especially at lags 1 and 2, than high-pass-filtered data. For Switzerland, we have 33 harvests (tithe and yield ratio) series to be tested, of which up to two-thirds give usable temperature–harvest results; more than half of these have Granger causality in the expected direction (i.e. from temperature to yields). Linearly detrended data give stronger indications of Granger causality at lag 1 and 3, whereas high-pass-filtered data give stronger indications of Granger causality at lag 2. In the case of Spain, where 23 series could have returned Granger causality test results, we find that at most only four do so – therefore, we have no strong evidence for Granger causality temperature–harvest relationships for Spain (Table 4).

Roughly half of the 28 “testable” pairs (i.e. the number of pairs that can be calculated) from Sweden return results for hydroclimate (Table A2). Most of these are in the expected direction. Relatively similar results are obtained for high-pass-filtered and linearly detrended data. For Switzerland, weak evidence is found for precipitation–harvest relationships with Granger causality. However, linearly detrended data give us somewhat stronger results at the risk of being spurious. We found for linearly detrended data that eight causalities were significant and that seven of these were directed from precipitation towards harvests. Only one pointed in the other direction. Very few results of precipitation–harvest relationships with Granger causality are obtained for Spain (Table 4). This is particularly the case using high-pass-filtered data.

For Sweden, for which we have 28 testable harvest series and the Stockholm barley/rye price series, roughly two-thirds return usable results, and in almost all cases they are in the expected direction of Granger causality. The high-pass-filtered data give slightly stronger results. In the case of high-pass-filtered data, at lag 1 all 20 out of 20 unambiguous results are in the expected direction (i.e. from yield to price). The harvest–price relationship for Switzerland, with 33 harvest series and the Basel rye and Zurich spelt price series, return usable results for over half the cases for lag 1 and 2 (Table 4). We tested all the harvest series against both the Basel rye and the Zurich spelt prices. The difference between high-pass-filtered and linearly detrended data is small. For Spain, 22 out of 23 series return unambiguous results at lag 1. At lags 2 and 3, almost all return unambiguous results when using linearly detrended data but only about half when using high-pass-filtered data. A higher proportion of the results for Spain for high-pass-filtered data than linearly detrended data are in the expected direction of Granger causality.

Table 4Granger causality test results based on tithe and yield series and temperature, hydroclimate, and grain price records. The maximum (m) order of the lags tested is 3 (column 1). Columns 2 to 7 give the results in pairs for 10-year high-pass-filtered and linearly detrended data, respectively, of the Granger causality test in the notation “” where “B” is the number of series that returned unambiguous test results and “A” is the number that only allowed for causality in the excepted direction. Wald testing performed at the p=0.05 significance level. After each region name we indicate n for the number of tithe and yield series available for testing.

4.1 The importance of climate for harvest yields

Relatively weak, but overall regionally consistent, climatic signals have been found in early modern harvest data across Europe (Sect. 3) regardless of the auto-correlative character of the data (Tables 1 and 2). The strongest climate signal is the positive association with summer soil moisture in Sweden (Sect. 3.1), the positive association with winter temperature and negative association with winter precipitation in Switzerland (Sect. 3.2), and the negative association with spring and annual mean temperature in Spain (Sect. 3.3). The Granger causality test reveals that highly significant climate–harvest associations tend to be in the expected direction (i.e. from climate to yield) (Sect. 3.4).

Our results (Sect. 3.1) obtained using high-pass-filtered climate and tithe data from Sweden are, in part, in line with previous studies for later historical periods using first-differenced data (e.g. Edvinsson et al., 2009). Furthermore, it is interesting to note the appearance of a temperature constraint during the growing season for Örebro and Stockholm counties, which suggests that the boundary between the temperature-constrained cultivation in northern Sweden and the precipitation-constrained cultivation in southern Sweden might historically, during colder climate periods (not shown), have been located further south than previously suggested (e.g. Utterström, 1957; Edvinsson et al., 2009).

For Switzerland, we confirm a significant negative association between winter precipitation and grain harvests (Sect. 3.2). However, no evidence was found for a negative association with autumn precipitation as previously reported (Pfister, 1988, 2005, 2007). The winter precipitation signal may, in part, be due to the flushing of nitrogen from manure spread on the fields, which mainly affected the lower part of the Swiss Plateau (Pfister, 1984). We also confirmed the reported positive correlation between warm springs and harvests, but we found the effect of warm winters to be stronger. The reported adverse effect of wet summers (Pfister and Wanner, 2021) could not be detected. This could possibly be related to the fact that we use average data for June to August, while the negative precipitation–harvest association is restricted mainly to the month of July (Pfister, 1988). Instead, though constrained to the high-frequency domain, the negative summer temperature–harvest relationship indicates a drought sensitivity (Table A5). The heterogeneous and weak climate–harvest association found for Spain (Sect. 3.3) is in line with previous results (Barriendos, 2005; Peña-Gallardo et al., 2019; Moreno et al., 2020). This is presumably directly related to the fact that Spain hosts among the most heterogeneous climatic conditions in Europe (Rodrigo and Barriendos, 2008; Beck et al., 2018). Nonetheless, the most apparent result, especially for the inland and southern Spain, is that cooler and wetter winters and springs contributed to better harvests. Only in Guadalajara on the central Spanish plateau was the opposite found.

The different detrending methods have partly revealed different correlation patterns. In the case of summer temperature for Sweden (Sect. 3.1) and Switzerland (Sect. 3.2), the high-pass-filtered data and the linearly detrended data even show opposite directions of correlations, where the high-pass-filtered data show negative (i.e. warmer temperatures meaning lower yields and vice versa) associations with summer temperatures and the linearly detrended data show positive (i.e. warmer temperatures meaning higher yields and vice versa) associations with summer temperatures (Fig. 6). To better constrain early modern climate–harvest relationships across all frequency bands, we would need to acquire harvest data that adequately capture multi-decadal grain yield variability and that are not dominated by trends on these timescales unrelated to actual growth conditions.

It might appear surprising that Sweden is the study region showing the strongest growing season drought sensitivity in grain harvest. However, the annual mean precipitation in the main agricultural areas in the southeast of Sweden is only about half of the rainfall in the main agricultural areas of Switzerland; furthermore, only about 15 % of the precipitation falls in March–May compared to about 25 % in Switzerland. Consequently, despite a shorter growing season, Swedish agriculture is more drought-prone, particularly during spring and early summer (De Toro et al., 2015). Whereas June–August mean temperature is comparable between Stockholm (17.4 ∘C) and Bern (18.0 ∘C, both from 1991–2020), the Swedish capital receives more sunshine and less precipitation during those months (789 vs. 696 h and 189 mm vs. 322 mm, respectively). The spring growing season of grain in Spain is considerably colder compared to the respective summer growing seasons in Sweden and Switzerland. At Guadalajara, at 700 m above sea level, the March–May mean temperature reaches only 12 ∘C, which is about 5 ∘C colder than the June–August mean at the Swedish and Swiss sites. Thus, it is not surprising that certain Spanish locations reveal positive correlations of grain harvest with winter and spring temperatures.

4.2 Climate–grain harvest associations during years of harvest failures

The comparatively weak correlations between seasonal climate parameters and grain harvest yields should not be interpreted as climate conditions playing a minor role for harvest failures and subsequent food crises in early modern Europe. While seasonal climate conditions only explain a fraction of the yield variations during most years, the majority of the severe harvest failures – those that could trigger famines during the early modern period – occurred during years with cold springs and summers, with prolonged periods of excessive precipitation right before, or during, harvest time (Pfister and Wanner, 2021). Consecutive years of poor harvests were especially associated with cold climatic anomalies (Ljungqvist et al., 2021).

Thus, climate played a far larger role for “shocks” to the food supply than what the relatively low climate–harvest correlations obtained here by themselves would imply. Very adverse climatic conditions for grain agriculture were responsible, partly or entirely, for most major food crises in early modern Europe (Alfani and Ó Gráda, 2017, 2018). This was especially the case as the same climatic conditions that lowered grain yields – cold springs and wet summers or severe droughts – also decreased pasture productivity and fodder availability (Pfister, 1988; White et al., 2018; Brázdil et al., 2019; Huhtamaa and Ljungqvist, 2021; Costello et al., 2023); it also favoured the development and spread of diseases among domestic animals (White, 2014; Newfield, 2015). Excess mortality among domestic animals, in turn, decreased the availability of manure to fertilize the grain fields, thus lowering the yields in subsequent years (Pfister and Wanner, 2021).

4.3 Limitations related to the climate data

Prior to the late seventeenth century, the Luterbacher et al. (2004) temperature and Pauling et al. (2006) precipitation reconstructions are solely based on proxy data, which only explain a fraction of the actual seasonal climate variability. For example, both the Luterbacher et al. (2004) temperature and the Pauling et al. (2006) precipitation field reconstruction are lacking local input data from Sweden during the period covered by the Swedish tithe series – thus, the lack of correlation with the Swedish tithe data is not surprising. The higher seasonal correlations with the Luterbacher et al. (2004) and Pauling et al. (2006) reconstructions with the Spanish tithe and yield records that only cover the eighteenth century indicate higher correlations by including early instrumental records in these reconstructions. Our findings imply that a lack of significant correlations between seasonal precipitation and harvest data is likely due to the limitations of proxy-based precipitation reconstructions. This highlights the need to develop new regional precipitation reconstructions, in the best case with a denser and longer proxy data network, and to improve the quality of existing ones.

For Switzerland, for which we have high-quality local precipitation and temperature data for all seasons (Pfister, 1992; Dobrovolný et al., 2010), we obtained more significant correlations than for Sweden and Spain for precipitation and for more seasons for temperature. However, limitations in the low-frequency domain might exist because documentary climate reconstructions based on the index method typically under-represent the full amplitude of low-frequency climate variations (Adamson et al., 2022). This may partly explain the highly significant correlations for Switzerland when using high-pass-filtered data compared to linearly detrended data (see Fig. 4; Table A4).

4.4 Limitations related to the harvest data

The Swedish tithe data contain numerous missing years and also years when the data may be considered uncertain (Myrdal and Söderberg, 1991). Furthermore, the Swedish tithe data for different counties partly cover different periods (Leijonhufvud, 2001; Hallberg et al., 2016) and thus capture different prevailing climate conditions. For Switzerland, an estimation of the actual harvest size is sometimes difficult since tithes were sold at auctions rather than collected in the field, although the authorities' controls were rather strict (Pfister, 1979). A problem in detecting climatic signals in parts of the tithe data, especially from Spain, is when tithes consisted of different types of grains with exact proportions of each changing over time (Le Roy Ladurie and Goy, 1982).

The varying climate sensitivity between tithe records and yield ratio records from the same region is not surprising as soil properties, elevation, and micro-climatic conditions additionally affected the climate–harvest yield associations. Variations in the yield data may partly be related to changes in farming methods and/or availability of manure for fertilization (Pfister and Wanner, 2021). Yield ratios from individual estates typically show low correlations among themselves and with tithe data over longer time spans (i.e. more than 10 years) except during more extreme climatic periods (Leijonhufvud, 2001). Differences between farms in ploughing, fertilizers, weeding, sowing intensity (per area), and so forth (Simpson, 1996; Hoffman, 1996; Gadd, 2011; Myrdal, 2011; Martínez-González et al., 2020) may to some extent offset potential climate signals at the local (farm) level, but they should be mitigated when averaging the data to regional means.

4.5 Human agency dominating long-term harvest yield changes

Considering that climate variables only explain parts of the harvest yield variations, past as well as present, it is also important to consider other factors when studying climate-dependent activities like agriculture (sensu Hulme, 2011; Haldon et al., 2018; van Bavel et al., 2019). This includes (i) a fading and non-linear relationship between seasonal climate and harvest yields at locations far from the climatological limits of a certain crop, (ii) poor harvests often resulting from single days or weeks of unfavourable weather conditions rather than seasonal average climate conditions, and (iii) the large degree to which harvest yields depended on factors related to human agency (e.g. socio-political and socio-economic settings, cultural traditions, infrastructure, and technology).

Moreover, early modern harvests were influenced by pests and diseases, seed quantity and quality, manure availability, access to draught animals, and availability of labour (Simpson, 1996; Gadd, 2011; Myrdal, 2011; Moreno et al., 2020; Pfister and Wanner, 2021). The lack of seed grain after consecutive harvest failures could also reduce the harvest in subsequent year(s) of good growth conditions (Appleby, 1979; Pfister, 1990; Bekar, 2019), as has been demonstrated for early modern Finland (Huhtamaa et al., 2022) but also for non-peripheral, fertile agricultural districts such as Scania, present-day southern Sweden (Brasch, 2016). The genetic variety of early modern grain types was larger than today. For example, in Sweden varieties of extremely fast-growing spring barley that could be sown in late spring existed (Leino, 2017). Such a genetic diversity of grain varieties, adapted to local environmental conditions (Forsberg et al., 2015, 2019), complicates comparisons between climate–harvest relationships through time and between regions.

Modern climate–grain harvest yield relationships are not necessarily the same as historical agrometeorological relationships. Agricultural practices changed during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries due to mechanization, chemical fertilizers, pesticides, and higher-yielding seed varieties, resulting in multiplied harvest yields. For example, “field inaccessibility” due to excessively wet soils, which reduces operability and increases soil compaction, posed a major hazard for grain production in northwestern Europe during the 1980–2010 period (Trnka et al., 2015). This type of hazard would have been very different for pre-industrial agriculture.

Using a coherent framework of statistical analyses, we re-assessed the temperature and hydroclimate signatures in grain harvest data among diverse environmental settings of early modern (ca. 1500–1800) Europe. We detected regionally consistent, but overall relatively weak, climate–harvest relationships. Even though the majority of the severe food crises during the early modern period were connected to climate anomalies, only a fraction of documented grain harvest variations can be explained by the available climate data. The strength of historical climate–harvest associations revealed here is similar to contemporary climate–grain yield relationships in Europe. Higher soil moisture have been found to be beneficial for harvests in Sweden, while warmer and drier winters favoured larger harvests in Switzerland. For Spain regionally more heterogeneous climate–harvest relationship patterns were found, with a dominating annual mean and spring temperature signal. The strength of the climate–harvest associations are somewhat weaker than the comparatively strong climate–grain price relationships previously reported by Esper et al. (2017) and Ljungqvist et al. (2022) (among others). We also found that climate–harvest correlations can change direction with frequency and in some regions with season (particularly for summer temperature in Switzerland and Sweden).

Broader empirical and methodological implications of this study include the need to (i) develop better precipitation reconstructions for the early modern period as the arguably greatest limitation to constrain climate–harvest relationships are stemming from the lack of such data; (ii) continue efforts to digitize already published harvest data and extract new harvest yield series from original archival research for additional regions and to reduce data gaps and uncertainties; (iii) explore changes in the frequency of climate extremes, and their effects on harvest yields, under different mean climate states; and (iv) further assess potential differences between the climate signal embedded in harvest yield and grain price data, including response differences to summer temperature. Further studies are also needed to assess grain quality, in addition to quantity, and their relationship to climate and their effects on grain prices during historical times.

Table A1Grain price data used for Granger causality analysis. Information about the grain type, covered period, missing values (“gaps” in percentage), the auto-correlation coefficient for a lag of 1 year, AR1, and the data source(s) is provided.

* An equal share of barley and rye prices whenever both are available.

Table A2Climate–harvest correlations for Sweden. Results using high-pass-filtered data are shown to the left of the vertical bar, and results using linearly detrended data are shown to the right of the vertical bar. Bold values indicate correlations significant at the p=0.05 level with a t test, and an asterisk (*) indicates significant correlations with the phase-scrambling test. All correlations for Sweden and their significance are shown in Fig. 3.

Table A3Climate–harvest correlations for Sweden for barley and rye tithe data separately. Results using high-pass-filtered data are shown to the left of the vertical bar, and results using linearly detrended data are shown to the right of the vertical bar. Bold values indicate correlations significant at the p=0.05 level with a t test, and an asterisk (*) indicates significant correlations with the phase-scrambling test.

Table A4Climate–harvest correlations for Switzerland. Results using high-pass-filtered data are shown to the left of the vertical bar, and results using linearly detrended data are shown to the right the vertical bar. Bold values indicate correlations significant at the p=0.05 level with a t test, and an asterisk (*) indicates significant correlations with the phase-scrambling test. TDJF indicates Dobrovolný et al. (2010) DJF temperature reconstruction, TJJA indicates Büntgen et al. (2006) Lötschental JJAS temperature reconstruction, PDJF indicates Pfister (1992) DJF precipitation indices, and PJJA indicates Pfister (1992) JJA precipitation indices. All correlations for Switzerland and their significance are shown in Fig. 4.

Table A5Climate–harvest correlations for Spain. Results using high-pass-filtered data are shown to the left of the vertical bar, and results using linearly detrended data are shown to the right of the vertical bar. Bold values indicate correlations significant at the p=0.05 level with a t test, and an asterisk (*) indicates significant correlations with the phase-scrambling test. All correlations for Spain and their significance are shown in Fig. 5.

We have used IDL and R (https://www.R-project.org/, R Core Team, 2022) version 3.6.3 to program the analysis codes used in this work. In R we used the “aod” package (https://cran.r-project.org/package=aod, Lesnoff and Lancelot, 2012) for the Wald test and the package “corrplot” (https://github.com/taiyun/corrplot, Wei and Simko, 2021) to generate the correlation matrices. Data were read from mixed files using “base” libraries for text files or “openxlsx” (https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=openxlsx, Schauberger and Walker, 2021) for Excel spreadsheet files. The maps in Fig. 1 were drawn in ArcMap 10.6 (program package of ArcGIS, ESRI, 2017) and then edited in Adobe Illustrator.