the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Insights into the Middle–Late Miocene palaeoceanographic development of Cyprus (eastern Mediterranean) from a new δ18O and δ13C stable isotope composite record

Alastair H. F. Robertson

Dick Kroon

The Middle to Late Miocene was a time of significant global climate change. In the eastern Mediterranean region, these climatic changes coincided with important tectonic events, which resulted in changes to the organisation of oceanic gateways, altering oceanic circulation patterns. The Miocene Climatic Optimum (MCO) is regarded as the most recent CO2-driven warming event in Earth's climate history and has been proposed as an analogue for future climate change. We present a ca. 12 Ma record of oxygen and carbon stable isotopes from the island of Cyprus to help constrain the nature and extent of Miocene palaeoceanographic changes in the eastern Mediterranean region. Cyprus exposes Neogene deep-sea pelagic sedimentary rocks which are suitable for stable isotope studies. Our composite geochemical record integrates data from the Lower to Upper Miocene succession at Kottaphi Hill along the northern margin of the Troodos ophiolite, with the Upper Miocene succession at Lapatza Hill in the north of Cyprus. Calcareous nannofossil biostratigraphy reveals that the composite record spans the Miocene Climatic Optimum's onset to the beginning of the Messinian Salinity Crisis (MSC). The new stable isotopic record reveals a complex interplay between global climate change and regional to local tectonic changes. In the earlier part of the record, global climate changes dominated; however, by the end of the Late Miocene, tectonic events culminated in isolation of the Mediterranean basins, resulting in a deviation from global open-ocean trends. Strontium (Sr) isotope analysis is used primarily to help constrain the age of the Miocene successions sampled and implies changes in the connectivity of the eastern Mediterranean basins during the Late Miocene. The combined data provide a useful reference for oceanographic changes in the eastern Mediterranean basins during the Miocene, compared to the global oceans.

- Article

(6571 KB) - Full-text XML

-

Supplement

(1082 KB) - BibTeX

- EndNote

Global climate changes during the Miocene are important analogues for modern climatic changes (You, 2010; Steinthorsdottir et al., 2021; Holbourn et al., 2022), especially because the Miocene epoch (ca. 23–5 Ma) was a time of significant climatic and environmental changes. For the global oceans, it is believed that a slight cooling during the Early Miocene was followed by a dramatic (ca. 4 °C) warming event at the onset of the Miocene Climatic Optimum (MCO), at ca. 17.9 Ma (Zachos et al., 2008; Holbourn et al., 2015; Westerhold et al., 2020). High temperatures related to the MCO ended at ca. 14.7 Ma, during a cooling event known as the Middle Miocene Climate Transition (MMCT) (Kennett et al., 1975; Holbourn et al., 2005; Super et al., 2020). Following the MMCT, a gentle cooling trend continued globally until the end of the Miocene (Zachos et al., 2008; Westerhold et al., 2020). Relatively little is known about the effects of the above changes regionally, especially in marginal seas such as the eastern Mediterranean. Together with climatic changes, the eastern Mediterranean Sea underwent tectonic changes on a regional to local scale during the Miocene, including extensive changes in ocean circulation patterns related to closure of several ocean gateways (Hsü et al., 1973a; Rouchy and Caruso, 2006; Robertson et al., 2012; Torfstein and Steinberg, 2020). During the Miocene, the oceanic gateway which connected the eastern Mediterranean Sea to the Indian Ocean to the east became greatly restricted and eventually closed completely (Hüsing et al., 2009; Torfstein and Steinberg, 2020). The connection between the Mediterranean Sea and the Atlantic Ocean to the west was lost completely during the Late Miocene (Krijgsman et al., 1999a; Flecker et al., 2015). This resulted in the isolation of the Mediterranean Sea from the global open ocean, leading to the well-known Messinian Salinity Crisis (MSC) (Hsü et al., 1973a; Rouchy and Caruso, 2006; Roveri et al., 2014).

Here, we present new oxygen and carbon stable isotope records from Lower to Upper Miocene deep-marine sediments in Cyprus, which provide an excellent reference for the eastern Mediterranean Sea. This new record was constructed in order to better understand the role and interplay of global climatic and regional to local tectonic events in the eastern Mediterranean region during the Miocene.

We begin with an overview of the Miocene palaeoceanography and tectonically driven changes in ocean connectivity, together with an explanation of relevant aspects of the Miocene geology of Cyprus.

1.1 Miocene δ18O and δ13C

Oxygen stable isotope records, mainly from deep ocean drilling, are the key to identifying and understanding important Miocene climatic events, notably the Miocene Climatic Optimum (MCO) (Zachos et al., 2008; Holbourn et al., 2015; Westerhold et al., 2020). Such events are now recognised in palaeoceanographic records globally using δ18O records and more recently using other methods such as Mg Ca and organic palaeotemperature proxies (Zachos et al., 2001; Westerhold et al., 2005; Zachos et al., 2008; Holbourn et al., 2015; Modestou et al., 2020; Sosdian et al., 2020; Sosdian and Lear, 2020; Super et al., 2020; Westerhold et al., 2020).

The onset of the MCO was marked by an abrupt decrease in δ18O at ca. 16.9 Ma. This falling δ18O trend, which is recorded in the global oceans, was associated with a ca. 4 °C increase in global temperature (Zachos et al., 2001; Westerhold et al., 2005; Zachos et al., 2008; Westerhold et al., 2020). The MCO represents a ca. 3 Myr greenhouse interval, which began at approximately 16.9 Ma and lasted until ca. 14.7 Ma (Zachos et al., 2008; Holbourn et al., 2015; Westerhold et al., 2020). The onset of this warming event is commonly attributed to a dramatic rise in CO2 levels, from ca. 400 to 500 ppm (You et al., 2009; Zhang et al., 2013; Holbourn et al., 2015). The Middle Miocene increase in CO2 can be explained by rapid eruption of the contemporaneous Columbia River basalts (Hodell et al., 1994; Foster et al., 2012; Reidel, 2015; Kasbohm and Schoene, 2018).

The rapid increase in δ13C at ca. 16.9 Ma indicates the onset of a positive carbon isotope excursion known as the Monterey Event, which lasted until ca. 13.5 Ma (Vincent and Berger, 1985; Holbourn et al., 2007; Holbourn et al., 2015). The approximate co-occurrence of the MCO with the Monterey Event indicates that the warming was coupled with a significant disruption of the global carbon cycle (Vincent and Berger, 1985; Holbourn et al., 2007; Sosdian et al., 2020).

The increase in organic carbon burial related to the Monterey Event is believed to have driven CO2 drawdown (Vincent and Berger, 1985; Flower and Kennett, 1993; Flower and Kennett, 1994; Sosdian et al., 2020), ending the MCO and starting the cooling event known as the Middle Miocene Climate Transition. Incorporation of CO2 into organic material, particularly at continental margins (e.g. Monterey Formation, California, USA) (Pearson and Palmer, 2000), is believed to have resulted in a global decrease in CO2 levels, following the highs of the MCO. Resultant increases in Antarctic bottom water and North Atlantic deep-water production, combined with a reduction in saline water movement from the Indian Ocean to the Southern Ocean, are believed to have resulted in global-scale changes in ocean circulation that, in turn, triggered further cooling (Flower and Kennett, 1994). The cooling event following the MCO is known as the Middle Miocene Climate Transition (MMCT). According to δ18O-based sea level reconstructions, the MMCT represents a dramatic three-step global cooling event, which involved three corresponding steps of extreme sea level fall. The final temperature decrease and corresponding sea level fall are believed to relate to the establishment of a permanent East Antarctic Ice Sheet (EAIS) (Kennett et al., 1975; Miller et al., 1991a; Kennett et al., 2004; Holbourn et al., 2005; Miller et al., 2005). This cooling event has also been associated with increased continental runoff and sediment flux, as inferred for the central Mediterranean (Malta) (John et al., 2003).

Following the MMCT, foraminiferal δ18O records indicate that global temperatures continued to cool gradually, with temperature and sea level fluctuations in the 1.2 Myr obliquity cycle (Miller et al., 2005; De Vleeschouwer et al., 2017). However, organic palaeothermometry (TEX86) of samples from northern Italy (Monte dei Corvi) implies that the western Mediterranean Sea remained warm at the start of the Late Miocene and then cooled dramatically at ca. 8 Ma (Tzanova et al., 2015).

The Late Miocene Carbon Isotope Shift (LMCIS) is equivalent to a ca. 1 ‰ decrease in benthic foraminiferal δ13C from ca. 7.2 to ca. 7 Ma, probably due to a decrease in marine organic carbon burial rates (Keigwin, 1979; Keigwin and Shackleton, 1980; Holbourn et al., 2018). The timing of the LMCIS coincides with the onset of the Late Miocene–Early Pliocene Biogenic Bloom (Dickens and Owen, 1999; Diester-Haass et al., 2004, 2005).

Eustatic sea level fall was previously inferred to be a cause of the loss of connection between the Atlantic Ocean and the proto-Mediterranean Sea, culminating in the Messinian Salinity Crisis (Hsü et al., 1973a, b; Adams et al., 1977; Hsü, 1978). However, benthic foraminiferal δ18O records imply that the sea level was relatively stable during the Messinian (Miller et al., 2020). Accordingly, it is now widely believed that regional to local tectonics, rather than eustasy, were critical to the Messinian isolation of the proto-Mediterranean Sea (Flecker et al., 2015).

1.2 Regional tectonics and ocean gateways

Tectonic processes played an important role in the development of the eastern Mediterranean during the Miocene. During the Paleogene, the Southern Neotethys remained partly open, with the first geological evidence of incipient continental collision of the Eurasian and northern African (Arabian) plates during the Eocene (Robertson et al., 2016; Darin and Umhoefer, 2022). The initial stage of collision resulted in a narrowing of the marine connection between the Southern Neotethys and the Indian Ocean by the Late Eocene (Robertson and Parlak, 2024). During the Early Miocene, the collision intensified, greatly reducing the deep-water connection with the Indian Ocean.

Marine connection between the proto-Mediterranean Sea and the Indian Ocean persisted until the Middle to Late Miocene, as indicated by combined palaeontological (Harzhauser et al., 2007), geological (Hüsing et al., 2009), and geochemical (Kocsis et al., 2008; Bialik et al., 2019) data. The remaining limited connectivity still allowed warm surface water to flow from the Indian Ocean through the Mediterranean into the Atlantic Ocean (Bialik et al., 2019), but this terminated during the Late Miocene (ca. 11 Ma) (Hüsing et al., 2009) in response to structural tightening of the suture zone.

During the Messinian, tectonic uplift related to the northwestward migration of the African plate resulted in the closure of the Betic Strait and the Riffian Corridor (Weijermars, 1988; Garcés et al., 1998; Krijgsman et al., 1999a; Krijgsman et al., 1999b; Ng et al., 2021). The closure of these ocean gateways eventually eliminated the Mediterranean–Atlantic marine connection, as indicated by sedimentary, magnetostratigraphic, and biostratigraphic evidence (Krijgsman et al., 1999a; Flecker et al., 2015).

The overall result of the convergence in both the west and the east was that the Mediterranean Sea became isolated from the global ocean at ca. 6 Ma, triggering the Messinian Salinity Crisis (MSC). During the MSC, in some areas the Mediterranean, the sea level dropped more than 1000 m relative to the open ocean (Hsü et al., 1973a; Rouchy and Caruso, 2006), and this, coupled with hyper-aridity, resulted in the deposition of thick evaporites within the Mediterranean basins after ca. 5.57 Ma.

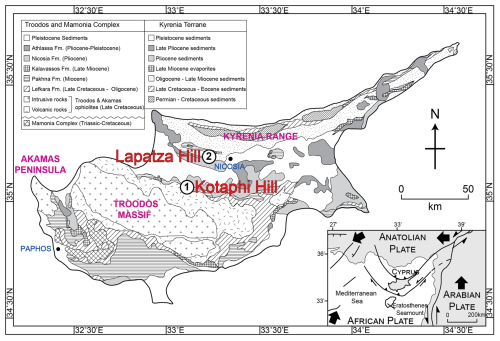

1.3 Miocene of Cyprus

The island of Cyprus constitutes three distinct tectono-stratigraphic entities (Fig. 1), each of which has a unique geological history: the Kyrenia Range in the north (Robertson and Woodcock, 1986; Robertson et al., 2024), the Troodos ophiolite in the island's centre (Gass and Masson-Smith, 1963; Moores and Vine, 1971), and the Mamonia Complex in the west (Lapierre, 1972; Robertson and Woodcock, 1979; Robertson, 1990; Robertson and Xenophontos, 1993) (Fig. 1).

Figure 1Outline geological map of Cyprus showing the Troodos Massif, the Mamonia Complex, and the Kyrenia Range and their sedimentary cover (modified from Kinnaird et al., 2011). Site locations for this study are also shown. Inset: tectonic setting of Cyprus in the eastern Mediterranean region (modified from Follows and Robertson, 1990; Robertson et al., 1991; and Payne and Robertson, 1995).

During the Mesozoic, the Mamonia Complex and the Kyrenia Range formed parts of the continental margin of the Southern Neotethys. During the Late Cretaceous, the Troodos ophiolite formed within the Southern Neotethys by spreading above a subduction zone. After tectonic amalgamation during the latest Cretaceous, the Troodos ophiolite and the Mamonia Complex were transgressed by a latest Cretaceous to Oligocene sequence of deep-water pelagic carbonates, known as the Lefkara Formation (Mantis, 1970; Robertson and Hudson, 1973; Robertson, 1976; Kähler and Stow, 1998; Lord et al., 2000; Balmer, 2024). The Troodos ophiolite and the Mamonia Complex were significantly uplifted during the Oligocene–Early Miocene. The main drivers were the continental collision between Arabia and the Taurides to the east and northward subduction/underthrusting of Southern Neotethyan remnants beneath Cyprus (Robertson, 1998). The uplift resulted in relative sea level fall, allowing the deposition of variable, shelf-depth sediments of the Miocene Pakhna Formation in southern Cyprus; these include hemipelagic carbonates, gravity-flow deposits, and localised coral reefs (Robertson, 1977; Follows and Robertson, 1990; Follows et al., 1996; Cannings et al., 2021).

The Pakhna Formation encompasses two reef-related members. The stratigraphically lower of these units, the Lower Miocene Terra Member, is dominated by framestones, with high levels of algal and coral biodiversity (Follows et al., 1996; Coletti et al., 2021). The stratigraphically higher Upper Miocene Koronia Member comprises a reef facies with abundant poritid corals (Follows and Robertson, 1990; Coletti et al., 2021), together with an off-reef facies composed of rhodolith-rich packstones, calcarenites, and chalks with scattered bivalve and poritid fragments (Follows and Robertson, 1990). Of particular relevance here, the Pakhna Formation includes nannofossil ooze (chalk) and planktic foraminifer-rich calcareous mudstones (marls) which were sampled for this study on the northern margin of the Troodos ophiolite.

The Pakhna Formation is overlain by various gypsum facies, known as the Kalavasos Formation, that are associated with the onset of the MSC (Hsü et al., 1973b; Krijgsman et al., 2002; Wade and Bown, 2006; Manzi et al., 2016). The gypsum accumulated in several small tectonically controlled basins around the periphery of the Troodos Massif (Robertson et al., 1995a).

The Miocene sedimentary succession of the Kyrenia Range in the north of Cyprus differs strongly from that of southern Cyprus. The Miocene of the north of Cyprus encompasses an Upper Eocene to Upper Miocene succession of variably deformed non-marine to relatively deep-marine conglomerates, sandstones, and mudstones, known as the Kythrea (Değirmenlik) Group (McCay et al., 2013; Robertson et al., 2014; Chen et al., 2022). The Early to Middle Miocene interval is dominated by mudrocks and siliciclastic gravity-flow deposits, which were deposited in a trench or foreland basin setting along the northern margin of the southern Neotethys (McCay et al., 2013). By the Late Miocene, the input of sand-sized siliciclastic sediments waned, allowing Tortonian mudstones and marls, known as the Yılmazköy Formation, to accumulate. With a further decrease in siliciclastic input, dominantly hemipelagic marls, associated with thin (< 25 cm) manganese-oxide-rich layers, accumulated during the Tortonian–Lower Messinian, termed the Yazılıtepe Formation (Robertson et al., 2019). The overall succession is capped by Messinian gypsum, known as the Lapatza (Mermertepe) Formation (Hakyemez et al., 2000; McCay et al., 2013). Marls of the Yazılıtepe Formation that are located to the south of the Kyrenia Range were also sampled during this research (Fig. 1).

2.1 Site selection

To ensure that the samples collected provide a continuous record of the Early–Late Miocene target time interval (ca. 17.5–5.33 Ma), several exposures were selected for logging and sampling. The approximate ages were already known for previously studied exposures. However, the likely age ranges of the new sections needed to be inferred initially based mainly on lithological correlations. The samples from the new successions were dated during this work using calcareous nannofossil biostratigraphy (Cannings, 2024). Following fieldwork and preliminary dating, two sections were selected with the aim of producing a composite succession spanning ca. 17.5–5.33 Ma, one on the north side of the Troodos ophiolite at Kottaphi Hill and the other to the south of Kyrenia Range at Lapatza Hill (Fig. 1). Other sections that proved to be less suitable for the composite succession are detailed in Cannings (2024).

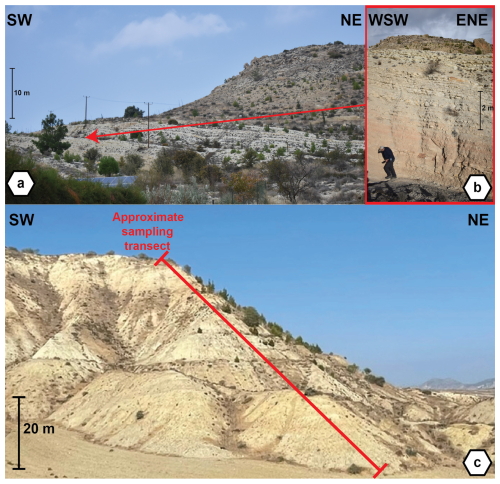

2.1.1 Kottaphi Hill

Kottaphi Hill (Koταφι, Kotaphi, or Kottafi) (35°2′50.40′′ N, 33°9′13.60′′ E) is located to the north of Agrokipia (Aγρoκηπια) village (Nicosia District) on the northern margin of the Troodos ophiolite (Fig. 1). Kottaphi Hill is a classic Miocene section of the Pakhna Formation (Mantis, 1972) and has been the subject of several studies (Follows and Robertson, 1990; Davies, 2001; Penttila, 2014; Athanasiou et al., 2021; Coletti et al., 2021). The Miocene succession (Fig. 2a, b) begins with ca. 60 m of cyclically bedded chalk and marl (i.e. couplets), representing the lower part of the Pakhna Formation (undifferentiated). This pelagic–hemiplegic interval is abruptly overlain by the Koronia Member, an interval of debris-flow deposits that are dominated by clasts (mainly angular) of shallow-water carbonates, including poritid corals (Follows and Robertson, 1990; Follows, 1992).

Figure 2Photographs showing the Kottaphi Hill succession (a), with the first interval of high-resolution sampling indicated (b) and with the sampled succession at Lapatza Hill (c), indicating the approximate sampling transect.

Previously, Davies (2001) logged and sampled the Kottaphi Hill succession at a resolution of > 20 cm), with the main aim of determining the relative roles of climate versus tectonics on sedimentation. The succession was dated as Burdigalian–Tortonian using calcareous nannofossil biostratigraphy, supported by limited carbon and oxygen stable isotope data. Davies (2001) described a thin (ca. 5 cm thick) cemented trace-fossil-rich manganese- and iron-rich layer in the middle part of the succession and interpreted this as a hardground. Based on spectral analysis, Davies (2001) suggested that the chalk–marl cyclicity (couplets) at Kottaphi Hill was controlled by regional to global changes in climate and sea level, i.e. Milankovitch cyclicity. Davies (2001) also identified the Monterey Excursion from the available δ13C record and linked a positive δ18O trend from 13 to 14 Ma with the isolation of the Mediterranean from the Indian Ocean. Building on the study of Davies (2001), Penttila (2014) used calcareous nannofossil biostratigraphy and strontium (Sr) isotope dating, together with foraminiferal abundance, and selected X-ray diffraction analysis to improve understanding of the Kottaphi Hill succession. She particularly identified the incoming of feldspar and clay-rich lithic fragments at ca. 10.6 Ma. This suggested that the adjacent Troodos Massif was near or above the seafloor by this time, allowing the erosion of extrusive ophiolitic rocks to take place. Penttila (2014) also discovered “ghost sapropels” (< 2% total organic carbon) towards the top of the marl–chalk succession (beneath the Koronia Member).

Subsequently, Athanasiou et al. (2021) collected samples from a 42.1 m thick interval of marl–chalk on the lower slopes of Kottaphi Hill. The samples collected underwent calcareous nannofossil, pollen and palynomorph, δ13C and δ18O, and total organic carbon analysis. The authors inferred that the organic carbon-rich layers at Kottaphi Hill were deposited in warm oligotrophic seawater, with strong water column stratification, and further suggested that these layers represent the precursors to the sapropels. They also identified the Mi3–Mi5 events (Miller et al., 1991a, 2020) and the CM5–CM7 episodes (Woodruff and Savin, 1985, 1991) in their δ13C and δ18O stable isotope record. Pollen and palynomorph analysis indicated that land nearby was densely vegetated before ca. 14.5 Ma. After ca. 13 Ma, a more open landscape existed, accompanied by nearby high rates of soil erosion.

2.1.2 Lapatza Hill

A ca. 60 m thick succession of well-bedded, laterally continuous marl that is exposed on Lapatza Hill (Lapatza Vouno) (35°14′44.70′′ N, 33°8′35.80′′ E) (Figs. 1 and 2c) belongs to the Tortonian–Lower Messinian Yazılıtepe Formation. The succession includes numerous thin (< 20 cm) manganese-rich layers (Necdet, 2002), similar to those described within the Yazılıtepe Formation in the Karpas Peninsula of NE Cyprus (Robertson et al., 2019). At Lapatza Hill, the marls are directly overlain by gypsum, representing the type section of the Lapatza (Mermertepe) Formation (Henson et al., 1949), of Middle–Late Messinian age, as elsewhere in Cyprus (McCay et al., 2013; Varol and Atalar, 2017; Artiaga et al., 2021).

2.2 Sampling

Samples were collected by hand using a geological hammer and a chisel to dig out and collect sediments so that they were unaffected by surface processes as far as possible. A shovel was sometimes needed to excavate a trench and take samples, especially where loose sediment cover needed to be removed, as at Lapatza Hill. The samples were collected at 5–25 cm intervals to facilitate high-resolution geochemical records. The sampling resolution varied for both sections based on the time interval covered and the inferred sedimentation rate. Previous studies (Davies, 2001; Penttila, 2014; Athanasiou et al., 2021) suggested that the section between 10.8 and 29.5 m at Kottaphi Hill coincided with the MCO and MMCT. Therefore, this part of the succession was subjected to the highest-resolution sampling (5 cm). Preliminary dating of the Lapatza Hill succession indicated a high (1–3 cm kyr−1) sedimentation rate; therefore, a larger (25 cm) sampling interval was used for this section. Sedimentary logs detailing the lithologies, sedimentary structures, and macrofossils (where present) were made for both successions during the sample collection.

2.3 Foraminifera

The planktic Praeorbulina–Orbulina lineage (Blow, 1956; Pearson et al., 1997; Aze et al., 2011; Spezzaferri et al., 2015) was used for the geochemical analysis. The foraminiferal species are present within the target time interval and are not known to vary in vital effects, depth habitat, or symbiotic association (Pearson et al., 1997).

Samples were washed using a 32 µm sieve to remove fine clay and silt fractions. Samples which were not easily broken up by wet-sieving were soaked in Milli-Q water and placed on a shaker plate for 90 min before being washed again over a 32 µm sieve. This process was repeated up to 3 times for the most resistant samples. The foraminiferal samples were then dried in an oven at 30 °C and dry-sieved into size fractions for foraminiferal picking.

2.4 Calcareous nannofossil biostratigraphy

Calcareous nannofossil biostratigraphy has been used successfully in Cyprus in several previous studies (Morse, 1996; McCay et al., 2013; Robertson et al., 2019; Cannings et al., 2021).

Calcareous nannofossils were identified using smear slides prepared using a standard method (Backman and Shackleton, 1983; Bown and Young, 1998) and then examined with a light microscope at a magnification of × 1000–1250. The calcareous nannofossil biostratigraphy used here is based on Backman et al. (2012), and the results presented are consistent with the updated Miocene Mediterranean biostratigraphy of Di Stefano et al. (2023).

2.5 Strontium isotope dating

The well-established strontium isotope dating technique (Elderfield, 1986) was previously used for the dating of mainly Neogene carbonate sediments in Cyprus (McCay et al., 2013; Penttila, 2014; Cannings et al., 2021). The isolation of the Mediterranean Sea during the Messinian Salinity Crisis (MSC) is believed to have resulted in anomalous 87Sr 86Sr ratios during this time, such that samples of this age range cannot be reliably dated using this method (Flecker and Ellam, 1999; Flecker et al., 2002; Flecker and Ellam, 2006).

Five samples of planktic foraminifera from the Praeorbulina–Orbulina lineage from the Kottaphi Hill succession, and five samples of planktic foraminifera also from the Praeorbulina–Orbulina lineage from the Lapatza Hill succession, were dated using the strontium (Sr) isotope method. These planktic foraminiferal samples were then analysed to help test and constrain the dating of the overall composite succession, as achieved by biostratigraphy. The strontium isotope analysis was carried out at the Scottish Universities Environmental Research Centre using a VG-Sector-54 thermal ionisation mass spectrometer. Further details of the methodology used for strontium isotope analysis are provided in the Supplement.

Strontium isotopic ages were calculated using the LOWESS Sr isotope Look-Up Table (Version 4: 08/04) (McArthur et al., 2001; McArthur and Howarth, 2004). The total errors were calculated by combining the uncertainties of the Sr isotopic analyses with the error of the LOWESS Sr isotope Look-Up Table (Version 4: 08/04) (McArthur et al., 2001; McArthur and Howarth, 2004).

2.6 Stable isotope analysis

A bulk carbonate (fine-fraction; ≤ 63 µm) and a planktic foraminiferal stable isotope record are presented below for the composite succession that was obtained from the Kottaphi Hill and Lapatza Hill successions. The combination of both bulk carbonate (fine-fraction) and planktic foraminiferal records provides the most complete isotope record possible for the target time interval by reducing the gaps in the record to a minimum. However, bulk carbonate and planktic foraminiferal records can differ due to variable vital effects in the biogenic components (Anderson and Cole, 1975; Reghellin et al., 2015); i.e. a planktic foraminiferal sample contains only one biogenic component, whereas a bulk carbonate sample contains multiple biogenic components and also their fine-grained matrix.

For the bulk analysis, 640 samples were broken up and dry-sieved through a 38 µm sieve in order to collect a concentrated sample of nannofossil carbonate and to reduce the likelihood of terrigenous components being present. The samples were then ground using a porcelain pestle and mortar to ensure a consistent, homogeneous fine powder. ∼ 0.5 mg of each powdered sample was then taken for isotopic analyses. All of the stable isotope measurements of the bulk carbonate (fine-fraction) samples were made in the Wolfson stable isotope ratio mass spectrometry suite at the University of Edinburgh on an Elementar precisION continuous flow stable isotope ratio mass spectrometer, using a Gilson autosampler equipped with an automated acidification system, a heated tray, and an iso FLOW system.

Isotopic measurements of 578 foraminifera samples were taken in the Wolfson stable isotope ratio mass spectrometry suite at the School of GeoSciences at the University of Edinburgh using a dual-inlet Thermo Electron Delta V Advantage stable isotope mass spectrometer, interfaced with a Kiel carbonate II device.

2.7 Age model

New age models were generated for both the Kottaphi Hill and Lapatza Hill successions.

For each succession, a preliminary age model was created based on calcareous nannofossil biostratigraphy. Sedimentation rates were calculated based on the depth/height difference between samples identified as bio-horizons. Samples that were not biostratigraphically dated were assigned tentative ages using a linear interpolation based on the calculated sedimentation rate. The final age model was produced using AnalySeries 2.0.8 (Paillard et al., 1996). The new δ18Oplanktic record produced for this study was used for this purpose and aligned with the North Atlantic δ18Obenthic compilation record of Cramer et al. (2009).

For the alignment, the new δ18Oplanktic record was filtered using multiple steps (20, 60, 100 kyr) of box filtering, in order to reduce “noise” and reveal only long-term trends and major perturbations. Identifiable marine isotope stages/events and major trends within the record were aligned with the reference record by creating tie points at the midpoints of such trends. This age modelling technique has uncertainty resulting from a combination of the uncertainties associated with the calcareous nannofossil biostratigraphy, the δ18Oplanktic record of this study, and the δ18Obenthic record used for the alignment (Cramer et al., 2009).

Age models were produced separately for both the Kottaphi Hill and Lapatza Hill successions using the same method. These records were then compared carefully to identify the most suitable splice point to combine the two records and so produce a composite record for the whole of the target time interval.

3.1 Sedimentary logs

3.1.1 Kottaphi Hill

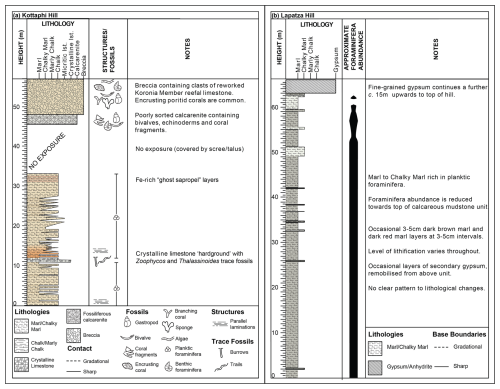

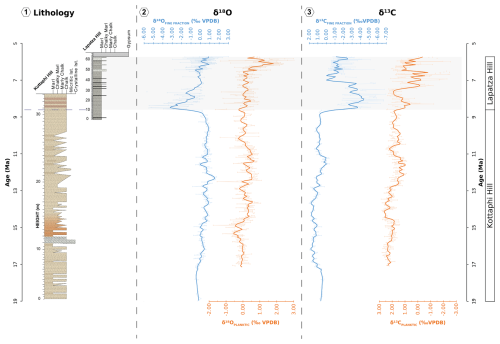

The sampled Kottaphi Hill succession begins ca. 10 m stratigraphically below the prominent hard layer which was previously interpreted as a “hardground” (Davies, 2001). A simplified stratigraphic log of this succession is shown in Fig. 3a, while a more detailed log is recorded in the Supplement.

Figure 3Simplified stratigraphic logs of (a) the Kottaphi Hill succession showing the occurrence of sedimentary structures and fossils up the succession and (b) the Lapatza Hill succession showing the approximate abundance of planktic foraminifera and the main lithological changes up the succession.

The measured succession at Kottaphi Hill begins with 10.97 m of alternating beds of light buff-coloured chalk and slightly darker buff-coloured calcareous marl. At 10.97 m, there is an abrupt lithological change to three hard grey limestone beds (15–30 cm thick), interbedded with darker, buff-coloured micritic limestone. The upper surfaces of each of the three limestone beds are characterised by well-preserved trace fossils (Thalassinoides, Diplocraterion, and Zoophycos), with evidence of preferential cementation and metal oxide precipitation. This interval is reinterpreted here as a firmground rather than a hardground (Cannings, 2024). Above the final cemented micritic limestone bed, chalk and calcareous marl interbeds start at 11.3 m. These beds are pinkish-red gradually fading to buff-coloured over ca. 4 m. Up-section, the abundance of chalk beds increases relative to marl beds. From 27.79 to 32.96 m, thick (30–85 cm) chalky marl beds are interbedded with thinner (5–20 cm) marl beds. Several soft marl beds within this facies have a distinctive dark reddish-brown colour. These marl layers are interpreted as oxidised (i.e. “ghost”) sapropels. Above this level, exposure is patchy to rare, mostly covered by reworked debris from the above units, and so was not sampled for stable isotope analysis.

3.1.2 Lapatza Hill

The succession sampled at Lapatza Hill (Fig. 3b) comprises 63.1 m of marl, with infrequent layers of darker-brown marl, dark-red marl, and chalky marl. Fine parallel laminations are present throughout the succession, becoming more prominent towards the top of the succession. Sedimentary structures (including observable bioturbation) are otherwise absent. This succession is abruptly overlain by a ca. 15 m thick interval of fine-grained alabastrine gypsum; this continues to the top of the hill where the section ends.

The marls are very rich in planktic foraminifera at the base; however, at ca. 52.5 m, their abundance decreases, especially in the softest marl beds. By ca. 61 m, foraminifera are completely absent. However, some foraminifera reappear in chalky marl beds at ca. 62 m, although their abundance rapidly decreases towards the contact with the overlying gypsum. Additionally, numerous thin (1–5 cm) dark-brown and red marl manganese- and iron-rich layers occur within the entire marl succession, although these were not sampled.

3.2 Calcareous nannofossil biostratigraphy

3.2.1 Kottaphi Hill

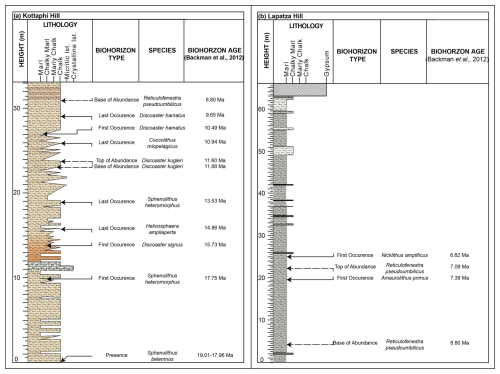

Figure 4a shows the ages obtained using calcareous nannofossil biostratigraphy for the samples from the Kottaphi Hill succession. Accordingly, the base of the succession is between 19.01 and 17.96 Ma, as indicated by the presence of Sphenolithus belemnos (Backman et al., 2012). The top of the sampled succession is slightly younger than 8.8 Ma, as indicated by an increase in the relative abundance of Reticulofenestra pseudoumbilicus just beneath the top of the succession. These dates indicate that the Kottaphi Hill succession has an average sedimentation rate of ca. 0.25 cm kyr−1. Calcareous nannofossil biostratigraphy indicates that the highest sedimentation rate was 0.33 cm kyr−1 between 11.88 and 11.60 Ma and that the lowest was 0.19 cm kyr−1 between 17.75 and 15.73 Ma. These sedimentation rates do not take account of diagenetic compaction that was, however, minor because there is no evidence of deep burial or deformation of either of the two successions studied.

Figure 4Stratigraphic logs of the successions sampled at Kottaphi Hill (a) and Lapatza Hill (b) with the height and nature of bio-horizons annotated, together with ages according to Backman et al. (2012). Bio-horizons based on relative abundance (Backman et al., 2012) are less quantitative than other bio-horizons and are marked with a dashed line.

3.2.2 Lapatza Hill

Figure 4b shows the ages inferred using calcareous nannofossil biostratigraphy for the samples from the Lapatza Hill succession. The increase in the relative abundance of Reticulofenestra pseudoumbilicus slightly above the base indicates that the base of the succession is older than 8.8 Ma (using the biostratigraphy of Backman et al., 2012). The first occurrence of Amaurolithus primus at ca. 19.5 m indicates an age of 7.39 Ma. These dates indicate that the Lapatza Hill succession has an average sedimentation rate (non-decompacted) of ca. 1.01 cm kyr−1. The calcareous nannofossil biostratigraphy indicates that the highest sedimentation rate was 1.08 cm kyr−1 between 8.8 and 7.39 Ma, whereas the lowest sedimentation rate was 0.92 cm kyr−1 between 7.39 and 7.09 Ma.

The calcareous nannofossil assemblages above the 25 m level in the Lapatza Hill succession are not age-diagnostic. Samples from the upper part of the section contain a diverse calcareous nannofossil assemblage; however, age-indicative species are absent. Discoaster spp. specimens are abundant in samples from the lower part of the succession but disappear above ca. 60 m.

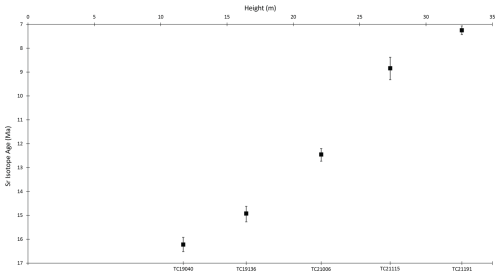

3.3 Strontium isotope dating

3.3.1 Kottaphi Hill

Sr isotope dating indicates that the succession at Kottaphi Hill, above the carbonate firmground, ranges from 16.22 Ma (with an error range of 16.01 to 16.46 Ma) to 7.25 Ma (with an error range of 6.86 to 7.82 Ma) (Fig. 5). The Sr isotopic ages retain their depositional order, with an average sedimentation rate (non-decompacted) of 0.27 cm kyr−1.

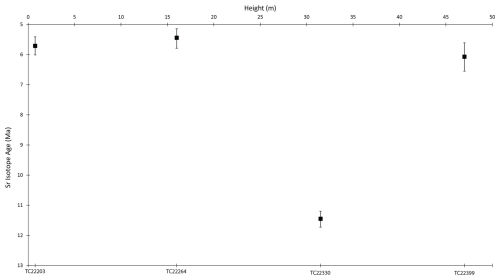

3.3.2 Lapatza Hill

The Sr isotope data for the Lapatza Hill succession indicate an age range of 11.45 Ma (with an error range of 10.9 to 12.24 Ma) to 5.44 Ma (with an error range of 5.139 to 5.66 Ma) (Fig. 6). The oldest age (lowest 87Sr 86Sr) is for sample TC22 330 from the 31.5 m level, whereas younger ages were calculated for the samples both above and below this. Either the heights of the samples up-section do not correlate with their age, or the ages determined do not represent the timing of biomineralisation of these samples of planktic foraminifera. However, there is no sedimentological or biostratigraphic evidence of the first alternative. Additionally, sample TC22 470, taken from a height of 62.75 m, has a strontium isotopic value (0.709241) outwith the LOWESS Sr isotope Look-Up Table (Version 4: 08/04) (McArthur et al., 2001; McArthur and Howarth, 2004), indicating that this does not represent a global seawater composition.

3.4 Age model

The new age model for Kottaphi Hill indicates that the succession sampled spans 18.96 Ma (Burdigalian) to 7.72 Ma (Tortonian). From the base of the succession to 10.97 m (17.15 Ma), the average sedimentation rate (non-decompacted) is calculated as 0.805 cm kyr−1, with an average (slower) sedimentation rate of 0.245 cm kyr−1 between 10.97 m (17.15 Ma) and the top of the succession sampled.

The new age model for Lapatza Hill spans 9.14 Ma (Tortonian) to 5.74 Ma (Messinian). From the base of the succession to 25 m (6.82 Ma), the average sedimentation rate is calculated as 1.099 cm kyr−1, with little variation. From 25 m (6.82 Ma) to the top of the succession, the sedimentation rate increased (3.627 cm kyr−1) (again non-decompacted).

The two sampled successions were combined to produce the composite temporal record. Figures showing the age model, together with the points used for its construction and the sedimentation rates derived from the age models for both sections, are provided in the Supplement. The composite temporal record points to any changes in climatic and environmental conditions throughout the whole of the time interval of interest. A small peak of more positive δ18O values in the δ18Oplanktic record is noted in both successions at 8.60 Ma. This level (8.60 Ma) was selected as the splice point to combine the two records, thus creating the representative composite record, taking account of the similarity in δ18Oplanktic, δ18Ofine fraction, δ13Cplanktic, and δ13Cfine fraction trends and values at this level. These spliced intervals provide a ca. 13.2 Myr record, from 18.95 Ma (Burdigalian) to 5.74 Ma (Messinian). This composite record covers the whole of the time interval of interest, from the onset of the Miocene Climatic Optimum to the onset of the Messinian Salinity Crisis.

3.5 Stable isotopes

3.5.1 δ18O

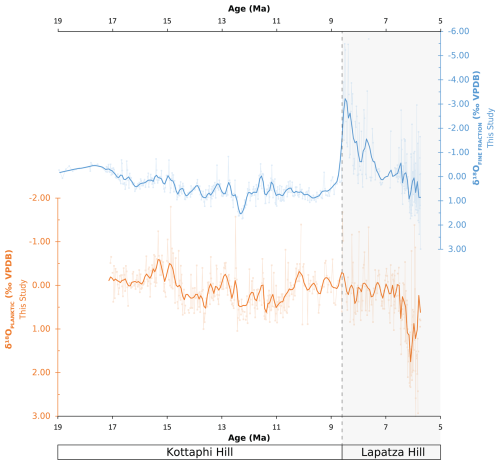

Figure 7 shows the δ18Oplanktic and δ18Ofine fraction records for the composite temporal record and allows comparisons between the two methods. Both records show a generally similar trend for the Kottaphi Hill succession. Although the δ18Oplanktic record appears to be more variable than the δ18Ofine fraction record, both display approximately synchronous peaks and troughs. Prior to the beginning of the δ18Oplanktic record, the δ18Ofine fraction record shows a very gradual decrease in δ18O (more negative values).

Figure 7Plot of δ18Oplanktic (orange) and δ18Ofine fraction (blue) versus age for the composite temporal record. Measurements are shown relative to VDPB. All measured data are shown with a thin line and box markers; the bold lines show the δ18O data smoothed by a locally weighted function over 60 kyr (see Supplement for additional information).

The two records show a marked divergence at the splice point, at the beginning of the sampled Lapatza Hill succession. While the δ18Oplanktic record for Lapatza Hill continues at a similar δ18O value to the Kottaphi Hill succession, the δ18Ofine fraction record exhibits a major (ca. 6.0 ‰ VDPB) offset between the two successions. The δ18Ofine fraction time series also records increased variability in the δ18O values for the Lapatza Hill succession compared to the Kottaphi Hill succession. The two stable isotope records (planktic and fine-fraction sample) show different trends for the Lapatza Hill succession. However, both records show the most positive δ18O values for the Lapatza Hill succession at ca. 6 Ma.

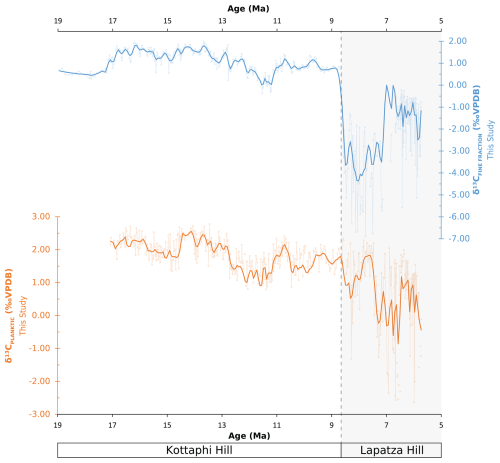

3.5.2 δ13C

The δ13C data for the composite temporal record are shown in Fig. 8. For the Kottaphi Hill succession, the two records (planktic and fine-fraction sample) follow a similar trend, although the δ13Cplanktic record is more variable than the δ13Cfine fraction record. The δ13Cplanktic values record a steep increase to more positive values in δ13C at ca. 14.6 Ma, as recorded in the δ13Cfine fraction record. Both records show a significant shift towards more negative values at the splice point between the Kottaphi Hill and Lapatza Hill records. In the δ13Cplanktic record, shortly above this shift, the values return to a similar level (1 ‰–2 ‰), as in the Kottaphi Hill succession. The shift in δ13C is more dramatic (ca. 4.5 ‰) in the δ13Cfine fraction, in which the values do not return to a similar level as in the Kottaphi Hill succession but instead remain lower. Following the splice point, the δ13Cplanktic and δ13Cfine fraction records show discrete trends. The δ13Cplanktic values record a second shift to more negative δ13C values at ca. 7.6 Ma, followed by a “saw-tooth” decrease until ca. 6.5 Ma, when values sharply increase, before once again decreasing until the end of the record. In the δ13Cfine fraction record, the values continue to decrease following the negative shift at the splice point, until ca. 8.5 Ma, when the values begin to increase before rapidly increasing to ca. 0.00 ‰ at ca. 7 Ma. The δ13Cfine fraction values steadily decrease from ca. 6.9 Ma until the end of the record.

Figure 8Plot of δ13Cplanktic (orange) and δ13Cfine fraction (blue) versus age for the composite temporal record. Measurements are shown relative to VDPB. All measured data are shown with a thin line and box markers; the bold lines show these δ13C data smoothed by a locally weighted function over 60 kyr (see Supplement for additional information).

4.1 Composite Early–Late Miocene temporal record

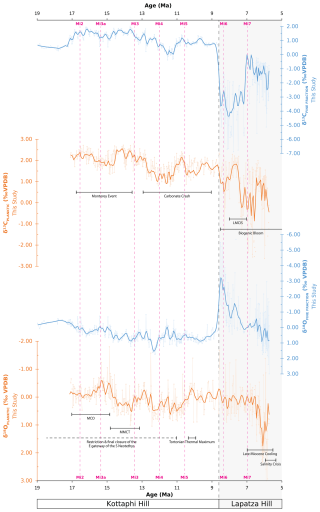

By combining the Kottaphi Hill and the Lapatza Hill data, a composite temporal record for the late Early Miocene (Burdigalian) to the Late Miocene (Messinian) could be constructed (Fig. 9). As this composite temporal record combines data from the two different successions sampled, specific features of the two sections (e.g. facies, diagenesis) need to be taken into account, as detailed in Cannings (2024).

Figure 9Stratigraphic logs of both the Kottaphi Hill succession and the Lapatza Hill succession, shown scaled to age, together with the δ18Oplanktic and δ18Ofine fraction records for the composite temporal record, and the δ13Cplanktic and δ13Cfine fraction records for the composite temporal record. All of the measured or calculated data are shown with box markers connected by a thin line. Bold lines show these data smoothed by a locally weighted function over 60 kyr.

4.2 Strontium isotope dating used to support the new age model

The strontium isotope dating of the planktic foraminifera samples from Kottaphi Hill is in good agreement with the calcareous nannofossil dating. The ages of the samples produced by the new age model are within the error range calculated from the Sr isotope analysis.

In contrast, the Sr isotope dating of the samples from Lapatza Hill is problematic. Sedimentological study of the succession (Cannings, 2024) did not reveal any evidence of large-scale reworking or structural disturbance. Whilst diagenetic alteration is a possibility, this process did not produce anomalous results in the stable isotope analyses of planktic foraminifera from the Lapatza Hill succession.

Previously anomalous 87Sr 86Sr values have been documented for samples of Messinian age and have been attributed to the onset of the Messinian Salinity Crisis (MSC). For example, apparently anomalous 87Sr 86Sr results have been documented from pre-evaporitic sequences in southern Türkiye, and attributed to variations in 87Sr 86Sr, due to the isolation of small, relatively proximal basins prior to the Messinian Salinity Crisis (Flecker and Ellam, 1999; Flecker et al., 2002; Flecker and Ellam, 2006). The anomalous 87Sr 86Sr values of all of the samples in this succession suggest that the onset of the MSC led to changes in the local 87Sr 86Sr of seawater ca. 2 million years before the deposition of the evaporites. Local changes in 87Sr 86Sr are likely to represent changes in the balance between ocean input and local changes in the hydrological cycle, as suggested by previous modelling of 87Sr 86Sr ratios in the eastern Mediterranean basins (in SW Türkiye) during the Late Miocene (Flecker et al., 2002). Modelling studies suggest that the closure of the eastern gateway of the southern proto-Mediterranean resulted in significant alterations to the hydrological cycle in the eastern Mediterranean region, with evaporation exceeding freshwater input (Karami et al., 2009), which in turn lead to variable 87Sr 86Sr values. The most likely explanation for the lack of correlation of sample height in the succession with the calculated age in the Lapatza Hill succession is that the Sr isotope values of the planktic foraminifera analysed do not reflect the Sr isotope values of the global seawater at the time of biomineralisation. Calcareous nannofossil biostratigraphy indicates that the conditions resulting in anomalous 87Sr 86Sr values were present from ca. 8 Ma until the end of the recorded data of this study.

4.3 Differences between stable isotope records

As noted above, the δ18Ofine fraction record (Fig. 7) shows a dramatic offset towards much more negative δ18O values at the splice point between the Kottaphi Hill and Lapatza Hill successions. Similarly, the δ13Cfine fraction record shows a dramatic offset (ca. 4.5 ‰) towards more negative δ13C values at the splice point. Following this offset, both fine-fraction records show different trends from the planktic records for the same sample sets from Lapatza Hill.

Interpretations based on fine-fraction measurements are generally not as well constrained as those based on planktic foraminiferal measurements, mainly because the former can be influenced by matrix composition. Facies observations, together with mineralogical and geochemical data, indicate that the samples from the Lapatza Hill succession have a greater terrigenous component compared to those from the Kottaphi Hill succession (Cannings, 2024). The isotopic signal of the terrigenous component was therefore necessarily measured together with the biogenic carbonate signal when the fine-fraction bulk samples from the Lapatza Hill succession were analysed. Both the δ18Oplanktic and the δ13Cplanktic records do not show a dramatic offset at the splice point. This supports the interpretation that the offset in the fine-fraction records is due to differences in the composition of the bulk samples.

A relatively low magnitude shift is noted in the δ13Cplanktic record compared to the fine-fraction bulk records (Fig. 8). This shift is likely to represent small differences between the local δ13Cseawater at each of the two localities. Localised more negative δ13C values may indicate the redeposition of isotopically light carbon from a nearby shelf during sea level changes, or the input of isotopically light carbon from the continent (Vincent et al., 1980; Vincent and Berger, 1985; Kouwenhoven et al., 1999).

For the Kottaphi Hill succession, the fine-fraction records are mainly influenced by the biogenic carbonate material present, as evidenced by the similarity between the fine-fraction and the planktic records. As a result, the fine-fraction records for Lapatza Hill are not suitable for interpreting climatic or oceanographic changes. The planktic record for Lapatza Hill is, however, relatively complete, limiting any need for an interpretation based on the fine-fraction record. On the other hand, the fine-fraction measurements of samples from Kottaphi Hill appear to be controlled by the stable isotopic composition of biogenic calcite. Therefore, the Kottaphi Hill fine-fraction records can aid interpretations of climatic and oceanographic changes. This is especially useful for the interval from ca. 19 to ca. 17 Ma when planktic foraminifera are absent or poorly preserved.

4.4 Palaeoceanographic implications

4.4.1 δ18O

Some useful interpretations and regional to global comparisons concerning oxygen isotope trends, palaeotemperature, and climatic evolution can be made based on the stable isotope records presented here (Fig. 10), in light of the geological setting.

Figure 10Plot of planktic and fine-fraction δ13C and δ18O versus age for the composite temporal record. Measurements are shown relative to VDPB. Both smoothed and calculated data are shown, as in Fig. 9. The timings of the Mi2–Mi7 events (Miller et al., 1991a, 2020) are also shown. The timing of several global- to regional-scale oceanographic events is indicated: (1) Monterey Event (Vincent and Berger, 1985; Holbourn et al., 2015), (2) Miocene Carbonate Crash (Lyle et al., 1995; Lübbers et al., 2019), (3) Biogenic Bloom (Dickens and Owen, 1999; Diester-Haass et al., 2004, 2005), (4) Late Miocene Carbon Isotope Shift (LMCIS) (Hodell et al., 1994), (5) Miocene Climatic Optimum (Zachos et al., 2008; Holbourn et al., 2015, Westerhold et al., 2020), (6) restriction (from ca. 20 Ma) and closure of the eastern gateway of the proto-Mediterranean (Hüsing et al., 2009; Bialik et al., 2019), (7) Miocene Climate Transition (Holbourn et al., 2015; Westerhold et al., 2020), (8) Tortonian Thermal Maximum (Westerhold et al., 2020), (9) Late Miocene Cooling (Herbert et al., 2016), (10) Messinian Salinity Crisis (Krijgsman et al., 1999a).

The trend towards more negative δ18Ofine fraction values suggests that some warming occured during the deposition of the lowermost part of the Kottaphi Hill succession sampled between 18.96 and 17.08 Ma. Relatively low δ18Ofine fraction and δ18Oplanktic values from 17.08 to 14.78 Ma can be correlated with the Miocene Climatic Optimum. This period of low δ18O was punctuated by three periods of inferred very high temperatures. The most prominent of these extreme periods took place at ca. 15.7, ca. 15.3, and ca. 14.9 Ma, consistent with an approximately 400 kyr cyclicity. Warm peaks in the ca. 400 kyr eccentricity cycle are known from palaeotemperature records of the Pacific Ocean (Miller et al., 2005, 2020). These intervals are assumed to represent an ice-free Earth during the MCO, possibly the most recent ice-free periods in Earth's history (Miller et al., 2005, 2020).

The beginning of the δ18O increase recorded at ca. 14.8 Ma correlates with Mi3a, marking the end of the MCO and the start of the MMCT (Miller et al., 1991a, b, 2020). Another positive δ18O excursion at 13.8 Ma marks the Mi3 event, representing the second cooling step associated with the MMCT (Miller et al., 1991a, b, 2020).

Open-ocean temperature records show slight warming and relatively stable temperatures following the first two cooling steps of the MMCT (Zachos et al., 2008; Miller et al., 2020; Westerhold et al., 2020). In contrast, the decreasing δ18O as recorded during this interval in Cyprus appears to indicate a local warming event. The cause of this apparent decoupling between the global climate and the eastern Mediterranean climate (using Cyprus as a reference) is uncertain but could relate to the dramatic restriction of the oceanic gateway between the proto-Mediterranean Sea and the Indian Ocean, which decreased the interchange between these two water masses. For example, the increasingly narrow shallow-water connection could have increased the volume of relatively warm seawater (heated directly by insolation and by warm river water input) input to the eastern Mediterranean basin. Both geological evidence (Hüsing et al., 2009; Robertson et al., 2016; Torfstein and Steinberg, 2020) and geochemical evidence (Bialik et al., 2019; Torfstein and Steinberg, 2020) indicate that the collision of the Arabian and Tauride continental crust was well advanced by the Early Miocene (ca. 20 Ma). This progressive closure left a mainly shallow seaway between the Indian Ocean and the Mediterranean Sea until complete closure at ca. 11 Ma (Hüsing et al., 2009). The shift to more negative δ18O values between 13 and 11 Ma in the records from Malta has also been attributed to the closure of this ocean gateway (Jacobs et al., 1996).

Following the above period of decreased δ18O, a positive excursion existed between 12.8 and 12.42 Ma, corresponding to the final cooling step of the MMCT and Mi4 (Miller et al., 1991b, 2020). The negative δ18O excursion at ca. 10.8 Ma was coeval with a warming event, as identified in a δ18Obenthic record from the western Pacific Ocean (Holbourn et al., 2013). This transient warming event is known as the Tortonian Thermal Maximum and is also reported in global temperature records (Westerhold et al., 2020). The warming event in the western Pacific Ocean was transient and ended after < 100kyr. However, the decreasing δ18O trend recorded in the eastern Mediterranean continued until ca. 10.2 Ma. An approximately coeval warming interval between ca. 11 and ca. 10 Ma is noted in Mg Ca palaeotemperature records from the equatorial Atlantic Ocean, but this is not recorded in the Pacific Ocean (Lear et al., 2003). By this time period, temperature changes in the proto-Mediterranean appear to reflect those in the Atlantic Ocean rather than the Pacific Ocean. This is consistent with limited connectivity between the proto-Mediterranean and the Indian Ocean by this time.

From ca. 10.2 Ma, a long-term increasing δ18O trend continued until the end of the record. This apparent cooling trend aligns with the long-term cooling trend between ca. 10 and ca. 6 Ma, as inferred from UK palaeotemperature records, and has been related to acceleration of Antarctic glaciation (Herbert et al., 2022). This positive δ18O trend was gradual until a more dramatic increase in δ18O at ca. 6.8 Ma. This may correspond to intense cooling from ca. 7 and ca. 6 Ma, termed “Late Miocene Cooling” (LMC), which is recorded in UK palaeotemperature records for high, mid-, and tropical latitudes in both hemispheres of the Atlantic and Pacific oceans (Herbert et al., 2016; Tanner et al., 2020).

Following the above dramatic δ18O increase, the recorded δ18O measurements rapidly increase, consistent with Late Miocene warming. However, this should be taken with caution because of the extensive changes in the hydrological cycle that are attributed to the Messinian Salinity Crisis (Flecker and Ellam, 1999, 2006; Flecker et al., 2002). As a result, high salinity levels are likely to have been an important control on δ18O in foraminiferal calcite during this interval.

4.4.2 δ13C

The δ13Cfine fraction record from Kottaphi Hill shows a period of elevated δ13C values between ca. 17 and ca. 13.5 Ma (Fig. 8). This is also recorded in the δ13Cplanktic record, albeit not as well defined (Fig. 8). This interval correlates with the well-documented Monterey global carbon isotope event (Vincent and Berger, 1985; Holbourn et al., 2007, 2015) (Fig. 10). The Monterey Event is associated with increased biological carbon isotope fractionation under high CO2 conditions, together with enhanced burial of organic matter on continental shelves, presumably as a result of eustatic sea level rise (Sosdian et al., 2020).

Both the δ13Cfine fraction and the δ13Cplanktic data for the composite temporal record show a gradual decrease in δ13C following the Monterey Event (Fig. 10). This decrease, which is also noted in open-ocean records (Cramer et al., 2009), has been related to increased CO2 drawdown following the high CO2 conditions of the Monterey Event (Vincent and Berger, 1985; Flower and Kennett, 1993; Flower and Kennett, 1994; Sosdian et al., 2020). Both the δ13Cfine fraction and δ13Cplanktic are especially low at ca. 12 Ma. This trend towards more negative δ13C may also relate to reduced primary productivity in the ocean, in response to the onset of the Miocene Carbonate Crash (Holbourn et al., 2018, 2021).

The δ13Cfine fraction and δ13Cplanktic records both show a shift to more positive values at ca. 10.8 Ma (Fig. 10). This corresponds to the Tortonian Thermal Maximum, which is recorded at a high magnitude in the δ18O records (Figs. 7 and 10).

At 7.2 Ma, a dramatic shift (ca. 2.5 ‰) to more negative carbon isotope values is shown in the δ13Cplanktic record (Fig. 10). This shift corresponds to the Late Miocene Carbon Isotope Shift (LMCIS) and the onset of the Late Miocene–Early Pliocene Biogenic Bloom (Dickens and Owen, 1999; Diester-Haass et al., 2004, 2005). The LMCIS has been linked to the intensification of global cooling and the Asian winter monsoon during the Late Miocene (Holbourn et al., 2018). The LCMIS has been explained by changes in ocean circulation, atmospheric circulation, or a combination of other factors, such as redistribution of nutrients, changes in photosynthetic pathways, or terrestrial weathering (Dickens and Owen, 1999; Diester-Haass et al., 2005; Holbourn et al., 2015; Tzanova et al., 2015; Herbert et al., 2016; Lyle et al., 2019). Although the LMCIS is recorded in the new δ13Cplanktic record, after this time the δ13Cplanktic record does not appear to reflect the open-ocean record from the North Atlantic Ocean (Cramer et al., 2009). This suggests that, after ca. 7.2 Ma (Early Messinian), the δ13C composition of the seawater in the eastern Mediterranean, specifically Cyprus, was no longer strongly influenced by global δ13C changes. A change in benthic foraminiferal assemblages and a shift to more negative δ13C values in the West Alboran Basin (western Mediterranean) at 7.17 Ma have been related to restriction of the Mediterranean–Atlantic gateway (Bulian et al., 2022). In the Lapatza Hill succession, a change in the benthic foraminiferal assemblage is noted at 7.23 Ma. Distinguishing between the effects of the LMCIS and the restriction of gateways in the west and/or the east is difficult. However, some effect of gateway closure is suggested by the discrete δ13C trend recorded in the Lapatza Hill succession after ca. 7.2 Ma. The well-documented constriction of the eastern gateway to the Indian Ocean during the Early Miocene, especially in SE Türkiye (Hüsing et al., 2009; Bialik et al., 2019; Torfstein and Steinberg, 2020), is likely to have influenced the more negative carbon isotope values.

4.5 Wider implications

This long-term δ13C and δ18O stable isotope record for the eastern Mediterranean basins is the first of its kind. This new record provides a useful reference section for future studies of Miocene eastern Mediterranean palaeoceanography. Whilst the trends recorded for global events, such as the MMCO, MMCT, and Monterey Event, were anticipated, this new record additionally reveals an extreme and long-lasting oxygen isotope excursion that coincides with the Tortonian Thermal Maximum. The apparent discrepancy in magnitude between this event in Cyprus and that recorded in global records warrants further consideration. The discrepancy could relate to the developing restriction in connectivity between the eastern Mediterranean Sea and the open ocean.

-

A shift in δ13C and δ18O fine-fraction values between two successions studied in Cyprus, the Kottaphi Hill succession and the Lapatza Hill succession, is explained by a larger terrigenous component in samples from the Lapatza Hill succession. Although fine-fraction samples can be used effectively for sites with a low terrigenous input (such as Kottaphi Hill), care must be taken to avoid recording signals unrelated to biogenic carbonate material where background terrigenous input is high.

-

The Early–Middle Miocene Monterey Event is clearly recorded in the composite temporal δ13C record that was produced by splicing of the two correlative successions (Lapatza Hill and Kottaphi Hill).

-

The new composite δ18O record from Cyprus allows the recognition of global climate events, including the Miocene Climatic Optimum, the Middle Miocene Climate Transition, and the Late Miocene Cooling. The decreasing δ18O trend, beginning at the Tortonian Thermal Maximum, appears to have continued for longer in the eastern Mediterranean Sea (using Cyprus as a reference) compared to global records. This could represent a local- to regional-scale warming event during a time when there was apparently extensive variation and disequilibrium, both between and within the Atlantic and Pacific oceans.

-

A negative shift in δ13Cplanktic values at ca. 7.2 Ma may correlate with the global Late Miocene Carbon Isotope Shift. However, it is difficult to distinguish the effects of the LMCIS from regional δ13C trends in Cyprus due to the partial closure of the Indian Ocean–Mediterranean and Mediterranean–Atlantic Ocean gateways.

-

This new composite stable isotope record from Cyprus also provides a useful reference section for the study of oceanographic changes in the eastern Mediterranean basins during the Miocene, compared to the western Mediterranean basins and globally.

All data used in this study are provided in Cannings et al. (2025), https://doi.org/10.1594/PANGAEA.987089.

The supplement related to this article is available online at https://doi.org/10.5194/cp-21-2501-2025-supplement.

TC, AHFR, and DK designed the research and carried out the initial fieldwork together. TC carried out the nannofossil dating and the analysis. TC, AHFR, and DK discussed and interpreted the resulting data. TC produced the figures. TC and AHFR wrote the article.

The contact author has declared that none of the authors has any competing interests.

Publisher's note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims made in the text, published maps, institutional affiliations, or any other geographical representation in this paper. While Copernicus Publications makes every effort to include appropriate place names, the final responsibility lies with the authors.

This article is part of the special issue “Paleoclimate, from observing modern processes to reconstructing the past: a tribute to Dick (Dirk) Kroon”. It is not associated with a conference.

This paper is based on studies carried out for the PhD degree by Torin Cannings at the University of Edinburgh. We thank Erica de Leau for her help and support with this research. We are also grateful to Simon Jung for his help with the production of the age model and with editorial aspects. We thank Colin Chilcott and Ulrike Baranowski for their assistance with stable isotope analysis. We also thank Anne Kelly, Vincent Gallagher, and Darren Mark from the Scottish Universities Environmental Research Centre, East Kilbride, for their assistance with the Sr isotopic analysis. Torin Cannings thanks Mehmet Necdet, Elizabeth Balmer, and Jacob Shearer for their help during fieldwork and also thanks Isabella Raffi for her guidance and training in calcareous nannofossil biostratigraphy. The authors also thank Isabella Raffi and Helmut Weissert for reviewing the article and providing valuable guidance for its improvement.

This research was funded by a Natural Environment Research Council E4 DTP studentship (grant no. NE/S007407/1).

This paper was edited by Simon Jung and reviewed by Isabella Raffi and Helmut Weissert.

Adams, C. G., Benson, R. H., Kidd, R. B., Ryan, W. B. F., and Wright, R. C.: The Messinian salinity crisis and evidence of late Miocene eustatic changes in the world ocean, Nature, 269, 383–386, https://doi.org/10.1038/269383a0, 1977.

Anderson, T. F. and Cole, S. A.: The stable isotope geochemistry of marine coccoliths; a preliminary comparison with planktonic foraminifera, J. Foramin. Res., 5, 188–192, https://doi.org/10.2113/GSJFR.5.3.188, 1975.

Artiaga, D., García-Veigas, J., Cendón, D. I., Atalar, C., and Gibert, L.: The Messinian evaporites of the Mesaoria basin (North Cyprus): A discrepancy with the current chronostratigraphic understanding, Palaeogeogr. Palaeocl., 584, 110681, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.palaeo.2021.110681, 2021.

Athanasiou, M., Triantaphyllou, M. V., Dimiza, M. D., Gogou, A., Panagiotopoulos, I., Arabas, A., Skampa, E., Kouli, K., Hatzaki, M., and Tsiolakis, E.: Reconstruction of oceanographic and environmental conditions in the eastern Mediterranean (Kottafi Hill section, Cyprus Island) during the middle Miocene Climate Transition, Revue de Micropaléontologie, 70, 100480, https://doi.org/10.1016/J.REVMIC.2020.100480, 2021.

Aze, T., Ezard, T. H. G., Purvis, A., Coxall, H. K., Stewart, D. R. M., Wade, B. S., and Pearson, P. N.: A phylogeny of Cenozoic macroperforate planktonic foraminifera from fossil data, Biol. Rev., 86, 900–927, https://doi.org/10.1111/J.1469-185X.2011.00178.X, 2011.

Backman, J. and Shackleton, N. J.: Quantitative biochronology of Pliocene and early Pleistocene calcareous nannofossils from the Atlantic, Indian and Pacific oceans, Mar. Micropaleontol., 8, 141–170, https://doi.org/10.1016/0377-8398(83)90009-9, 1983.

Backman, J., Raffi, I., Rio, D., Fornaciari, E., and Pälike, H.: Biozonation and biochronology of Miocene through Pleistocene calcareous nannofossils from low and middle latitudes, Newsl. Stratigr., 45, 221–244, https://doi.org/10.1127/0078-0421/2012/0022, 2012.

Balmer, E. M.: Interaction of deep and shallow-water sedimentary processes in southwest Cyprus, within the Eastern Mediterranean region, University of Edinburgh, PhD thesis, https://doi.org/10.7488/era/5421, 2024.

Bialik, O. M., Frank, M., Betzler, C., Zammit, R., and Waldmann, N. D.: Two-step closure of the Miocene Indian Ocean Gateway to the Mediterranean, Sci. Rep., 9, 8842–8842, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-45308-7, 2019.

Blow, W. H.: Origin and evolution of the Foraminiferal Genus Orbulina d'Orbigny, Micropaleontology, 2, 57–57, https://doi.org/10.2307/1484492, 1956.

Bown, P. R. and Young, J. R.: Techniques in: Calcareous Nannofossil Biostratigraphy, edited by: Bown, P. R., Paleoceanography, Chapman and Hall, London, 2, 16–28, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-011-4902-0_2, 1998

Bulian, F., Kouwenhoven, T. J., Jiménez-Espejo, F. J., Krijgsman, W., Andersen, N., and Sierro, F. J.: Impact of the Mediterranean-Atlantic connectivity and the late Miocene carbon shift on deep-sea communities in the Western Alboran Basin, Palaeogeogr. Palaeocl., 589, 110841, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.palaeo.2022.110841, 2022.

Cannings, T.: Middle-Late Miocene palaeoceanographic development of Cyprus (E. Mediterranean) based on integrated study of δ18O and δ13C stable isotope records, supported by Mg Ca palaeothermometry, nannofossil biostratigraphy, Sr isotopic dating, sedimentology and other geochemical data, unpublished PhD thesis, University of Edinburgh, 412 pp., https://doi.org/10.7488/era/4125, 2024.

Cannings, T., Balmer, E. M., Coletti, G., Ickert, R. B., Kroon, D., Raffi, I., and Robertson, A. H. F.: Microfossil and strontium isotope chronology used to identify the controls of Miocene reefs and related facies in NW Cyprus, J. Geol. Soc. London, 178, https://doi.org/10.1144/jgs2020-081, 2021.

Cannings, T., Robertson, A. H F., and Kroon, D.: δ18O and δ13C stable isotope data from a new composite sediment record, Cyprus (Eastern Mediterranean), PANGAEA [dataset], https://doi.org/10.1594/PANGAEA.987089, 2025.

Chen, G., Robertson, A. H. F., and Wu, F. Y.: Detrital zircon geochronology and related evidence from clastic sediments in the Kyrenia Range, N Cyprus: Implications for the Mesozoic-Cenozoic erosional history and tectonics of southern Anatolia, Earth-Sci. Rev., 233, https://doi.org/10.1016/J.EARSCIREV.2022.104167, 2022.

Coletti, G., Balmer, E. M., Bialik, O. M., Cannings, T., Kroon, D., Robertson, A. H. F., and Basso, D.: Microfacies evidence for the evolution of Miocene coral-reef environments in Cyprus, Palaeogeogr. Palaeocl., 584, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.palaeo.2021.110670, 2021.

Cramer, B. S., Toggweiler, J. R., Wright, J. D., Katz, M. E., and Miller, K. G.: Ocean overturning since the late Cretaceous: Inferences from a new benthic foraminiferal isotope compilation, Paleoceanography, 24, https://doi.org/10.1029/2008PA001683, 2009.

Darin, M. H. and Umhoefer, P. J.: Diachronous initiation of Arabia-Eurasia collision from eastern Anatolia to the southeastern Zagros Mountains since middle Eocene time, Int. Geol. Rev., 64, 2653–2681, https://doi.org/10.1080/00206814.2022.2048272, 2022.

Davies, Q. J.: Climatic and tectonic controls on deep water sedimentary cyclicity: evidence from the Miocene to Pleistocene of Cyprus, unpublished PhD thesis, Open University, United Kingdom, https://doi.org/10.21954/ou.ro.0000d558, 2001.

De Vleeschouwer, D., Vahlenkamp, M., Crucifix, M., and Pälike, H.: Alternating Southern and Northern Hemisphere climate response to astronomical forcing during the past 35 m.y., Geology, 45, 375–378, https://doi.org/10.1130/G38663.1, 2017.

Dickens, G. R. and Owen, R. M.: The Latest Miocene-Early Pliocene biogenic bloom: A revised Indian Ocean perspective, Mar. Geol., 161, 75–91, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0025-3227(99)00057-2, 1999.

Diester-Haass, L., Meyers, P. A., and Bickert, T.: Carbonate crash and biogenic bloom in the late Miocene: Evidence from ODP Sites 1085, 1086, and 1087 in the Cape Basin, southeast Atlantic Ocean, Paleoceanography, 19, https://doi.org/10.1029/2003PA000933, 2004.

Diester-Haass, L., Billups, K., and Emeis, K. C.: In search of the late Miocene-early Pliocene “biogenic bloom” in the Atlantic Ocean (Ocean Drilling Program Sites 982, 925, and 1088), Paleoceanography, 20, https://doi.org/10.1029/2005PA001139, 2005.

Di Stefano, A., Baldassini, N., Raffi, I., Fornaciari, E., Incarbona, A., Negri, A., Bonomo, S., Villa, G., Di Stefano, E., and Rio, D.: Neogene-Quaternary Mediterranean calcareous nannofossil biozonation and biochronology: A review, Stratigraphy, 20, 259–302, https://doi.org/10.29041/strat.20.4.02, 2023.

Elderfield, H.: Strontium isotope stratigraphy, Palaeogeogr. Palaeocl., 57, 71–90, https://doi.org/10.1016/0031-0182(86)90007-6, 1986.

Flecker, R. and Ellam, R. M.: Distinguishing climatic and tectonic signals in the sedimentary successions of marginal basins using Sr isotopes: An example from the Messinian salinity crisis, Eastern Mediterranean, J. Geol. Soc. London, 156, 847–854, https://doi.org/10.1144/GSJGS.156.4.0847, 1999.

Flecker, R. and Ellam, R. M.: Identifying Late Miocene episodes of connection and isolation in the Mediterranean–Paratethyan realm using Sr isotopes, Sediment. Geol., 189–203, https://doi.org/10.1016/J.SEDGEO.2006.03.005, 2006.

Flecker, R., De Villiers, S., and Ellam, R. M.: Modelling the effect of evaporation on the salinity-87Sr 86Sr relationship in modern and ancient marginal-marine systems: The Mediterranean Messinian Salinity Crisis, Earth Planet. Sc. Lett., 203, 221–233, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0012-821X(02)00848-8, 2002.

Flecker, R., Krijgsman, W., Capella, W., de Castro Martíns, C., Dmitrieva, E., Mayser, J. P., Marzocchi, A., Modestu, S., Ochoa, D., Simon, D., Tulbure, M., van den Berg, B., van der Schee, M., de Lange, G., Ellam, R., Govers, R., Gutjahr, M., Hilgen, F., Kouwenhoven, T., Lofi, J., Meijer, P., Sierro, F. J., Bachiri, N., Barhoun, N., Alami, A. C., Chacon, B., Flores, J. A., Gregory, J., Howard, J., Lunt, D., Ochoa, M., Pancost, R., Vincent, S., and Yousfi, M. Z.: Evolution of the Late Miocene Mediterranean–Atlantic gateways and their impact on regional and global environmental change, Earth-Sci. Rev., 150, 365–392, https://doi.org/10.1016/J.EARSCIREV.2015.08.007, 2015.

Flower, B. P. and Kennett, J. P.: Middle Miocene ocean-climate transition: High-resolution oxygen and carbon isotopic records from Deep Sea Drilling Project Site 588A, southwest Pacific, Paleoceanography, 8, 811–843, https://doi.org/10.1029/93PA02196, 1993.

Flower, B. P. and Kennett, J. P.: The middle Miocene climatic transition: East Antarctic ice sheet development, deep ocean circulation and global carbon cycling, Palaeogeogr. Palaeocl., 108, 537–555, https://doi.org/10.1016/0031-0182(94)90251-8, 1994.

Follows, E. J.: Patterns of reef sedimentation and diagenesis in the Miocene of Cyprus, Sediment. Geol., 79, 225–253, https://doi.org/10.1016/0037-0738(92)90013-H, 1992.

Follows, E. J. and Robertson, A. H. F.: Sedimentology and structural setting of Miocene reefal limestones in Cyprus, Troodos 1987. Symposium, edited by: Malpas, J., Moore, E.M., Panagiotou, A., Xenophontos, C., Cyprus Geological Survey Department, Nicosia, 207–215, INIST 19716441, 1990.

Follows, E. J., Robertson, A. H. F., and Scoffin, T. P.: Tectonic controls on Miocene reefs and related carbonate facies in Cyprus, Models for carbonate stratigraphy from Miocene reef complexes of Mediterranean regions, edited by: Franseen, E. K., Esteban, M., Ward, W. C., and Rouchy, J.-M., SEPM Society for Sedimentary Geology, 295–315, https://doi.org/10.2110/csp.96.01.0295, 1996.

Foster, G. L., Lear, C. H., and Rae, J. W. B.: The evolution of pCO2, ice volume and climate during the middle Miocene, Earth Planet. Sc. Lett., 341, 243–254, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2012.06.007, 2012.

Garcés, M., Krijgsman, W., and Agustí, J.: Chronology of the late Turolian deposits of the Fortuna basin (SE Spain): implications for the Messinian evolution of the eastern Betics, Earth Planet. Sc. Lett., 163, 69–81, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0012-821X(98)00176-9, 1998.

Gass, I. G. and Masson-Smith, D.: The geology and gravity anomalies of the Troodos Massif, Cyprus, Philos. T. Roy. Soc. S.-A, 255, 417–467, 1963.

Hakyemez, Y., Turhan, N., Sonmez, I., and Sumengen, M.: Kuzey Kıbrıs Turk Cumhuriyeti'nin Jeolojisi [Geology of the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus], unpublished report of MTA (Maden Tektik ve Arama), Genel Mudurlugu Jeoloji Etutleri Diaresi, Ankara, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/283461780_KUZEY_KIBRIS'IN_TEMEL_JEOLOJIK_OZELLIKLERI_-_MAIN_GEOLOGICAL_CHARACTERISTICS_OF_NORTHERN_CYPRUS (last access: 6 October 2025), 2000.

Harzhauser, M., Kroh, A., Mandic, O., Piller, W. E., Göhlich, U., Reuter, M., and Berning, B.: Biogeographic responses to geodynamics:: A key study all around the Oligo-Miocene Tethyan Seaway, Zool. Anz., 246, 241–256, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcz.2007.05.001, 2007.

Henson, F. R. S., Browne, R. V., and McGinty, J.: A synopsis of the stratigraphy and geological history of Cyprus, Quarterly Journal of the Geological Society, 105, 1–41, https://doi.org/10.1144/GSL.JGS.1949.105.01-04.03, 1949.

Herbert, T. D., Lawrence, K. T., Tzanova, A., Peterson, L. C., Caballero-Gill, R., and Kelly, C. S.: Late Miocene global cooling and the rise of modern ecosystems, Nat. Geosci., 9, 843–847, https://doi.org/10.1038/ngeo2813, 2016.

Herbert, T. D., Dalton, C. A., Liu, Z., Salazar, A., Si, W., and Wilson, D. S.: Tectonic degassing drove global temperature trends since 20 Ma, Science, 377, 116–119, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abl4353, 2022.

Hodell, D. A., Benson, R. H., Kent, D. V., Boersma, A., and Rakic-El Bied, K.: Magnetostratigraphic, biostratigraphic, and stable isotope stratigraphy of an Upper Miocene drill core from the Salé Briqueterie (northwestern Morocco): A high-resolution chronology for the Messinian stage, Paleoceanography, 9, 835–855, https://doi.org/10.1029/94PA01838, 1994.

Holbourn, A., Kuhnt, W., Schulz, M., and Erlenkeuser, H.: Impacts of orbital forcing and atmospheric carbon dioxide on Miocene ice-sheet expansion, Nature, 438, 483–487, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature04123, 2005.

Holbourn, A., Kuhnt, W., Schulz, M., Flores, J.-A., and Andersen, N.: Orbitally-paced climate evolution during the middle Miocene “Monterey” carbon-isotope excursion, Earth Planet. Sc. Lett., 261, 534–550, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2007.07.026, 2007.

Holbourn, A., Kuhnt, W., Clemens, S., Prell, W., and Andersen, N.: Middle to late Miocene stepwise climate cooling: Evidence from a high-resolution deep water isotope curve spanning 8 million years, Paleoceanography, 28, https://doi.org/10.1002/2013PA002538, 2013.

Holbourn, A., Kuhnt, W., Kochhann, K. G. D., Andersen, N., and Sebastian Meier, K. J.: Global perturbation of the carbon cycle at the onset of the Miocene Climatic Optimum, Geology, 43, 123–126, https://doi.org/10.1130/G36317.1, 2015.

Holbourn, A. E., Kuhnt, W., Clemens, S. C., Kochhann, K. G. D., Jöhnck, J., Lübbers, J., and Andersen, N.: Late Miocene climate cooling and intensification of southeast Asian winter monsoon, Nat. Commun., 9, 1584, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-03950-1, 2018.

Holbourn, A., Kuhnt, W., Clemens, S. C., and Heslop, D.: A ∼ 12 Myr Miocene record of East Asian monsoon variability from the South China Sea, Paleoceanography and Paleoclimatology, 36, https://doi.org/10.1029/2021PA004267, 2021.

Holbourn, A., Kuhnt, W., Kochhann, K. G. D., Matsuzaki, K. M., and Andersen, N.: Middle Miocene climate–carbon cycle dynamics: Keys for understanding future trends on a warmer Earth?, Understanding the Monterey Formation and similar biosiliceous units across space and time, edited by: Aiello, I. W., Barron, J. A., and Ravelo, A. C., Geological Society of America, https://doi.org/10.1130/2022.2556(05), 2022.

Hsü, K. J.: The Messinian salinity crisis – Evidence of Late Miocene eustatic changes in the world ocean, Naturwissenschaften, 65, 151–151, https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00440344, 1978.

Hsü, K. J., Cita, M. B., and Ryan, W. B. F.: 43. The origin of the Mediterranean evaporites, Initial Reports of the Deep Sea Drilling Project, U.S. Government Printing Office, 13, 1203–1231, https://doi.org/10.2973/dsdp.proc.13.143.1973, 1973a.

Hsü, K. J., Ryan, W. B. F., and Cita, M. B.: Late Miocene desiccation of the Mediterranean, Nature, 242, 240–244, https://doi.org/10.1038/242240a0, 1973b.

Hüsing, S. K., Zachariasse, W. J., Van Hinsbergen, D. J. J., Krijgsman, W., Inceöz, M., Harzhauser, M., Mandic, O., and Kroh, A.: Oligocene-Miocene basin evolution in SE Anatolia, Turkey: Constraints on the closure of the eastern Tethys gateway, edited by: van Hinsbergen, D. J. J., Edwards, M. A., and Govers, R., Geol. Soc. Spec. Publ., 311, 107–132, https://doi.org/10.1144/SP311.4, 2009.

Jacobs, E., Weissert, H., Shields, G., and Stille, P.: The Monterey event in the Mediterranean: A record from shelf sediments of Malta, Paleoceanography, 11, https://doi.org/10.1029/96PA02230, 1996.