the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Early Holocene cold snaps and their expression in the moraine record of the eastern European Alps

Sandra M. Braumann

Joerg M. Schaefer

Stephanie M. Neuhuber

Christopher Lüthgens

Alan J. Hidy

Markus Fiebig

Glaciers preserve climate variations in their geological and geomorphological records, which makes them prime candidates for climate reconstructions. Investigating the glacier–climate system over the past millennia is particularly relevant first because the amplitude and frequency of natural climate variability during the Holocene provides the climatic context against which modern, human-induced climate change must be assessed. Second, the transition from the last glacial to the current interglacial promises important insights into the climate system during warming, which is of particular interest with respect to ongoing climate change.

Evidence of stable ice margin positions that record cooling during the past 12 kyr are preserved in two glaciated valleys of the Silvretta Massif in the eastern European Alps, the Jamtal (JAM) and the Laraintal (LAR). We mapped and dated moraines in these catchments including historical ridges using beryllium-10 surface exposure dating (10Be SED) techniques and correlate resulting moraine formation intervals with climate proxy records to evaluate the spatial and temporal scale of these cold phases. The new geochronologies indicate the formation of moraines during the early Holocene (EH), ca. 11.0 ± 0.7 ka (n = 19). Boulder ages along historical moraines (n = 6) suggest at least two glacier advances during the Little Ice Age (LIA; ca. 1250–1850 CE) around 1300 CE and in the second half of the 18th century. An earlier advance to the same position may have occurred around 500 CE.

The Jamtal and Laraintal moraine chronologies provide evidence that millennial-scale EH warming was superimposed by centennial-scale cooling. The timing of EH moraine formation coincides with brief temperature drops identified in local and regional paleoproxy records, most prominently with the Preboreal Oscillation (PBO) and is consistent with moraine deposition in other catchments in the European Alps and in the Arctic region. This consistency points to cooling beyond the local scale and therefore a regional or even hemispheric climate driver. Freshwater input sourced from the Laurentide Ice Sheet (LIS), which changed circulation patterns in the North Atlantic, is a plausible explanation for EH cooling and moraine formation in the Nordic region and in Europe.

- Article

(19215 KB) - Full-text XML

-

Supplement

(13186 KB) - BibTeX

- EndNote

The transition from the Younger Dryas (YD; 12.9–11.7 ka; e.g., Alley, 2000) to the Holocene (ca. 11.7 ka to present, e.g., Walker et al., 2008) is an important period for studying the climate system, its forcings and its feedbacks. Climatic conditions shifted from glacial to full interglacial conditions within approximately 2 millennia, between 12 and 10 ka (e.g., Cheng et al., 2020; Marcott et al., 2013; Rasmussen et al., 2006). This general warming trend was interrupted by abrupt centennial-scale cooling that appears linked to freshwater input into the North Atlantic (e.g., Bjorck et al., 1997; Hald and Hagen, 1998; Nesje et al., 2004; Thornalley et al., 2010). The climatic shift from the YD to the early Holocene (EH) was accompanied by a multitude of major environmental changes that are interconnected, including the melting of ice caps and glaciers in both hemispheres, changes in the atmospheric composition and in circulation patterns, and the reorganization of ocean currents (e.g., Clark et al., 2012; Denton et al., 2021; Shakun et al., 2015). Human-induced warming since the beginning of the industrial era is on a trajectory to lead to changes of similar magnitude in our environmental system, yet at an even faster pace (Beniston et al., 2018; Gobiet et al., 2014). By investigating the timing of YD–EH warming and its perturbations, we can broaden our knowledge on natural drivers and physical mechanisms that modulated the climate system at that time. Information on climate oscillations obtained from this major natural transition – from glacial to interglacial conditions – provides a valuable foundation for disentangling natural and anthropogenic forcings and their respective relevance. New knowledge in this field is particularly useful in the light of the ongoing transition from an interglacial to an industrialized world.

Glaciers respond to climate fluctuations sensitively and are important elements for understanding the climate of the past (Huston et al., 2021; Roe et al., 2017). Reconstructing former ice margins allows for deciphering glacier fluctuations across time and space and informs us of climate variations that drove these changes. Mountain glaciers in alpine, melt-dominated regimes are most sensitive to changes in summer temperature and to a lesser extent to changes in precipitation (e.g., Oerlemans, 2005; Rupper and Roe, 2008; Steiner et al., 2008). At the end of the Late Glacial (LG), YD cooling resulted in glacier stabilization or readvance in the European Alps and led to the deposition of moraine sets, whose estimated Equilibrium Line Altitudes (ELAs) are approximately 250 to 350 m below ELAs of glaciers during the Little Ice Age (LIA; e.g., Ivy-Ochs, 2015). These moraines are termed “Egesen” moraines and have been subject of numerous cosmogenic nuclide studies that have advanced our understanding of glacier responses to cooling during the LG (e.g., Cossart et al., 2012; Federici et al., 2008; Ivy-Ochs et al., 2009, 2006; Kelly et al., 2004; Kerschner and Ivy-Ochs, 2008). In parallel, the first attempts had been made to produce direct ages of younger moraines that were identified inboard the presumable Egesen moraines but outboard historical LIA margins (Ivy-Ochs et al., 2006; Kerschner et al., 2006). Based on their morphostratigraphy, these moraine ridges were postulated as type localities for Preboreal glacier advance, for instance the Kartell moraines in the Verwall area and the Kromer moraines in the Silvretta Massif, both in the Eastern Alps (e.g., Faedrich, 1979; Gross et al., 1978). Kartell moraines are today placed into the latest YD (Egesen-III). Recalculated 10Be ages of Kromer moraines suggest moraine deposition during the EH around 10 ka (Ivy-Ochs et al., 2006; Kerschner et al., 2006; Moran et al., 2016b). Dating efforts that address presumable EH moraines continued toward the Central Alps and Western Alps and have produced chronologies that substantiate moraine formation between 12 and 10 ka, although not necessarily synchronously (Baroni et al., 2017; Boxleitner et al., 2019a, b; Cossart et al., 2012; Hofmann et al., 2019; Moran et al., 2016a, b, 2017; Protin et al., 2021, 2019; Schimmelpfennig et al., 2012, 2014; Schindelwig et al., 2012). In a few recent studies this pattern of moraine deposition has been confirmed in the Eastern Alpine region (Bichler et al., 2016; Moran et al., 2016a, 2017). The youngest dated EH moraine is located in the Ochsental, a valley adjacent to the sites discussed in this study (Braumann et al., 2020). The relevance of this chronology lies in the finding that glaciers in the valley had melted back to historical sizes around 10 ka and that they have remained within these limits throughout the Holocene, which is consistent with complementary paleoproxy records from the Eastern Alps (e.g., Dietre et al., 2014; Nicolussi and Patzelt, 2000; Patzelt, 2016).

To intensify our knowledge on EH glacier configurations in the Eastern Alps, where directly dated moraine ages remain sparser compared to the Western Alps and Central Alps, we conducted a geochronological study in two glaciated catchments in the Silvretta region in the Eastern Alps. We applied state-of-the-art cosmogenic nuclide techniques to date moraines inboard presumable LG ice margins to constrain the timing of Holocene cold phases recorded in the moraine record. We chose this region for two reasons: first, moraine sets that postdate the LG phase are well preserved in the Silvretta Massif and show multi-ridge structures. These geomorphological features promise insights into repeated Holocene cooling at times when glaciers were larger than during the LIA. Second, in addition to comparable cosmogenic nuclide records in the region (Braumann et al., 2020; Ivy-Ochs et al., 2006; Moran et al., 2016b), high-quality paleoenvironmental, archeological, and historical information on Holocene climate, which complements the moraine record, is available (Dietre et al., 2014; Kasper, 2015, 2013; Nicolussi, 2010; Patzelt, 2019).

The primary objective of this study is to generate more detailed and robust moraine chronologies in the eastern Alpine region, which contribute to our understanding of the spatial and temporal pattern of glacier advances throughout the Holocene with an emphasis on the EH. We correlate the new moraine chronologies with moraine records and climate proxy data from the Alpine region and from other glaciated regions in the Northern Hemisphere and identify climate signals that are coherent with Holocene glacier and climate evolution in the Silvretta Massif. Finally, we discuss possible links between climatic trigger events and EH cold snaps, which manifest in the moraine record of the Northern Hemisphere.

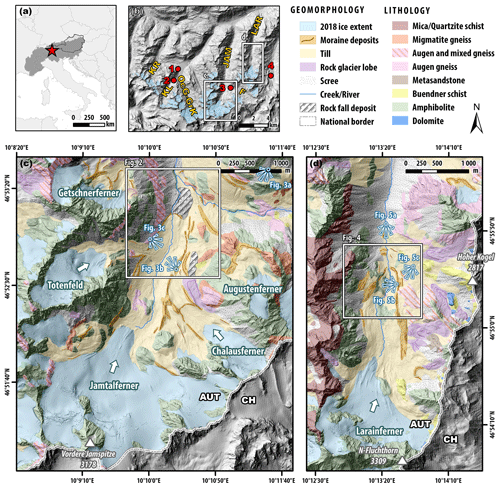

The study sites are located at the north-facing side of the Silvretta Massif, a mountain range in the transition zone between the eastern European Alps and western European Alps at the border of Austria and Switzerland (Fig. 1a). Moraine sets from two adjacent valleys, the Jamtal (JAM) and the Laraintal (LAR), were investigated and used for glacier reconstructions. Both valleys are north–south oriented, drain northwards into the Danube catchment, and are at present glaciated only in their highest sections (> 2400 m a.s.l.; Fig. 1b). The main and most prominent glacier of the Jamtal is the Jamtalferner, with an area of approximately 2.8 km2 (DEM 2018, provided by Land Tirol – tiris, 2018). Smaller glaciers, such as the Totenfeld, the Getschnerferner, and the Augustenferner, have retreated to cirque positions and are not connected to the valley glacier today (Fig. 1c). The situation is different in the neighboring Laraintal, where the Larainferner, which covers about 1 km2 (DEM 2018), is the only glacier still present in the valley (Fig. 1d).

Figure 1Location and lithology of investigated glaciated catchments. (a) Central Europe with the Alpine mountain range highlighted in dark gray and Austria outlined with black line. The Silvretta Massif (star symbol) is located in the westernmost part of the Eastern Alps. (b) North-facing section of the Silvretta Massif. Blue shading illustrates glacier extents in the year 2012 (Fischer et al., 2015). Jamtal (JAM) and Laraintal (LAR) are subject of this study. Moraine chronologies of Kromertal (KR), Klostertal (KL), and Ochsental (OcG-GrK) will be discussed later in this article (Braumann et al., 2020; Moran et al., 2016b). Red circles mark locations of subfossil tree findings: Bielerhöhe (1; Patzelt, 2019), Klostertal (2; Nicolussi, 2010), Futschöltal (F) (3; Patzelt, 2019), Las Gondas (4; Dietre et al., 2014; Nicolussi, 2010). (c) Updated geological and geomorphological maps of Jamtal and (d) Laraintal, modified from Fuchs and Oberhauser (1990). Viewpoints from which photos in Figs. 3 and 5 were taken are denoted with white and blue symbols. AUT stands for Austria, and CH stands for Switzerland. Digital elevation models (DEMs) provided by © Land Tirol (resolution 1 m) and © swisstopo (resolution 0.5 m).

The closest meteorological station recorded a mean annual atmospheric temperature of 3.1 ∘C averaged over the period 1981–2010 (station number 101949; 1587 m a.s.l.; BMNT, 2016). The mean annual precipitation measured at the same station amounts to 1087 mm yr−1 for the same reference period, with snow cover present on 175 d yr−1 on average. Precipitation is also measured in proximity to the Jamtalferner tongue (2400 m a.s.l.) and yields an annual mean of 1507 mm yr−1 (reference period 1989–2017; Fischer et al., 2019). Since the end of the LIA, all Silvretta glaciers have retreated in response to almost continuous warming and have lost about two-thirds of their areas relative to the LIA maximum (Fischer et al., 2021; WGMS, 2018). Geodetic mass balance estimates of Silvretta glaciers document increased losses within recent decades (Fischer et al., 2021). While geodetic mass balance averaged across all Silvretta glaciers amounted to −0.2 ± 0.1 m w.e. yr−1 in the reference period from 1969–2002, this value increased to −0.8 ± 0.2 m w.e. yr−1 between 2006–2018. For Jamtalferner and Larainferner, mass losses from 2006–2018 are quantified to −1.0 ± 0.2 and −0.8 ± 0.2 m w.e. yr−1, respectively.

The Silvretta Massif contains some of the oldest rocks of the Eastern Alps with a presumed depositional age in the Precambrian followed by several metamorphic events (Bertle, 1973; Maggetti and Flisch, 1993). Lithology in the region consists of crystalline rocks, which are part of the Upper Eastern Alpine tectonic unit, more precisely the Silvretta–Seckau nappe (Fuchs and Oberhauser, 1990; Schuster, 2015). Rocks at the Jamtal and Laraintal formed during the Permian and experienced repeated faulting prior to and throughout the Alpine orogeny and are thus metamorphic (Friebe, 2007, and references therein). Predominant rock types in the study area are different gneiss variations and amphibolites (Fig. 1c and d). Rock samples that were collected from moraines had quartz yields – the target mineral for the applied cosmogenic nuclide method – ranging from 0.3 % to 26.1 %, with a median of 3.9 % (Table S1 in the Supplement).

3.1 Principle of 10Be surface exposure dating (SED)

Glaciers erode into bedrock and transport rock material to their margins. When glaciers are stationary for several years (or longer), linear landforms – moraines – that consist of glacial debris accumulate at their ice margins. Dating these moraines unravels the timing of glacier stabilization or rather the beginning of glacier retreat and allows the reconstruction of glacier configurations of the past. For 10Be SED – the cosmogenic nuclide approach used in this study – rock samples were extracted from boulder surfaces deposited along moraines. Sub-rounded to rounded boulders were prioritized for sampling. Compared to angular boulders, (sub-)rounded ones are more likely to have been carved out of bedrock by glacial flow. When these englacially or subglacially transported boulders melted out of glacial ice, their surfaces were for the first time exposed to high-energy cosmic radiation. Secondary cosmic rays interact with Si and O in quartz and produce radionuclides, among others 10Be (Lal, 1988). The annual production rate of 10Be is well constrained today, and the accumulation of the radionuclide is used to determine the duration of exposure by quantifying 10Be in rock surfaces of moraine boulders (Gosse and Phillips, 2001).

3.2 Geomorphological mapping and rock sample collection

We build upon geological and geomorphological maps, which were produced in previous studies and which were the basis for further detailed field investigations in the years of 2018 to 2020 (Fischer et al., 2019, 2015; Fuchs and Oberhauser, 1990; Hertl, 2001). In the course of a general survey of the Jamtal and the Laraintal area, we updated preexisting maps according to our own mapping. We then focused on the mapping of glacial features and placed particular emphasis on the fine structure of moraines that were presumably deposited during the LIA, and ridges that were identified outboard these moraines. The dating of these structures promises to shed light onto the timing of climate perturbations, which favored moraine formation when glaciers were still relatively large compared to their present-day configurations. In order to ensure robust landform age calculations, we took three or more rock samples from each selected ridge, provided that they fulfilled our sample selection criteria described in detail in Braumann et al. (2020; their Appendix S-Table 1). In total, 27 samples were extracted from boulders using hammer and chisel and an electric saw. Geographic coordinates of sampled boulders were measured using a hand-held GPS device. Strike and dip of sampled surfaces were quantified with a geological compass. Sample elevations were taken from the DEM of 2018 (x–y–z resolution 1 m, © Land Tirol). Shielding was calculated using the ArcGIS “Skyline” toolbox.

3.3 Sample preparation and age calculation

All samples were processed at the Cosmogenic Isotope Laboratory of the Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory (LDEO) following the geochemical standard protocol for quartz preparation and the extraction of 10Be (LDEO, 2012a, b; Schaefer et al., 2009). Prior to quartz digestion using concentrated hydrofluoric acid, approximately 180 µg of the LDEO 9Be carrier made of deep-mine beryl was added to the samples (carrier concentration ca. 1000 ppm). Samples LAR-19-14 and LAR-19-16 with extremely low quartz yields of 0.3 %–0.4 %, equivalent to ca. 2.6–2.7 g of purified quartz per sample, were treated differently. Due to their small sample sizes combined with our EH age estimates, we expected low total numbers of cosmogenic 10Be atoms in the samples. For these samples we adopted a sample preparation procedure where 9Be carrier is reduced and replaced with Fe carrier. Only ca. 100 µg 9Be carrier was added during digestion and then ca. 100 µg of Fe (concentration 1000 mg L−1) was added to the samples prior to hydroxide precipitation (as Be(OH)2 + Fe(OH)2), subsequent to the cation columns step. The Fe addition allowed us to maintain manageable sample volumes, which facilitates the handling of the samples. This procedure was recommended for exceptionally low-level samples based on unpublished experimental data that suggests it optimizes 10Be counting efficiency at the Center for Accelerator Mass Spectrometry (CAMS) facility, Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (LLNL) (Alan J. Hidy, personal communication, 2020). We proceeded with subsequent steps of sample preparation according to the LDEO protocol (LDEO, 2012a). Isotope ratios (10Be 9Be) in samples were measured at CAMS-LLNL using the 07KNDSTD3110 standard with a 10Be 9Be ratio of 2.85 × 10−12 (Nishiizumi et al., 2007).

Exposure ages were calculated using the online calculator formerly known as the CRONUS-Earth online calculator (v3; Balco et al., 2008). We applied the regional Swiss production rate (Claude et al., 2014), and “Lm” scaling to account for site-specific nuclide production. All 10Be boulder ages are based on the arithmetic mean of three to five replicate AMS measurements and are presented with 1σ analytical uncertainties, including a 1 % uncertainty on the carrier concentration. Moraine ages represent arithmetic means of exposure ages of three or more boulder ages. Uncertainties reported with moraine ages include the production rate uncertainty (for the Swiss production rate ca. 6.3 %) in addition to the analytical and carrier uncertainty and were propagated in quadrature. Identification of potential outliers was accomplished following the χ2 statistics implemented in the online calculator.

Corrections of exposure ages for seasonal snow cover were not applied. First, samples were primarily taken from boulder tops or their upper sections, preferably located at windswept locations to minimize potential snow cover (see Supplement, Sect. S5). Second, if exposure ages were significantly influenced by snow effects, age dispersion would be expected among boulders embedded in the same moraine but whose shapes and exposures vary. Our data do not show a significant bias of this type; therefore, snow cover effects appear to be insignificant at our study sites. However, if a snow correction was applied to a boulder assuming a 1 m thick snowpack that is preserved over 4 months and has a snow density of ca. 0.3 g cm−3 (estimates based on modern values; BMLRT, 2021), its exposure age would become around 5 %–6 % older (Gosse and Phillips, 2001).

The preservation of striations on rock surfaces and the general condition of boulder surfaces in the valleys suggest that erosion has not significantly impacted their surfaces since deposition. Therefore, all ages that are presented and discussed in the following represent values without any erosion correction applied. However, in some studies addressing the Holocene timescale, an erosion rate of 1 mm ka−1 is used (André, 2002). To test the sensitivity of our ages to this erosion rate, we recalculated our data using this value and find that ages become at most 1 % older (median 0.8 %; Table S3), an age shift that is not significant on the 1σ level and that does not change our interpretation of the data.

4.1 Geomorphology

In both valleys, distinct moraine sets, which mark Holocene paleo-ice margins, are preserved. We numbered the moraines from the youngest (J0) to the oldest (J5) at Jamtal and moraines at Laraintal from L1 to L5 in analogy.

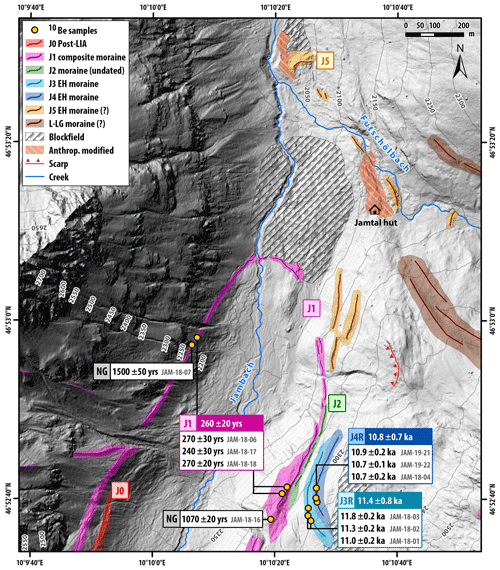

4.1.1 Jamtal

At Jamtal, the innermost moraine we address in this article is J0. The moraine was deposited at the left-lateral valley flank, inboard the presumable LIA moraine (J1; Fig. 2). The age of deposition of J0 falls into the period between the end of the LIA and the turn of the 20th century according to Fischer et al. (2019) and a historical map that was composed in the years between 1870–1877 (K. u. k. Militärgeographisches Institut, 1870–1887). J0 and J1 are punctuated by an approximately 100 m wide drainage channel, which evolved along the flowline of a former tributary glacier (Totenfeld, Figs. 3a and A1c). With numerous bedrock outcrops along the valley flank and a slope of > 35∘, the terrain is steep and impedes the accumulation moraines higher up (Fig. 3b). On the right-lateral side slope angles are in turn lower (5–35∘) and allowed the formation and preservation of multi-ridge moraine complexes (J1 to J4; Figs. 2, A1d and f). J1 consists of fresh, blocky debris with little to no lichen colonialization. Pioneer plants grow in voids in between blocks, whereas segments with more fine sediment are covered with a thin vegetation layer (Fig. A1a–c). In some sections, J1 is several tens of meters wide, which contrasts with the adjacent J2, which has a maximum width of about 8 m. J2 is located in a depression between J1 and a till-covered slope, on top of which J3 and J4 were deposited (Fig. A1e–f). J2 is rich in fine sediment but does not feature boulders that meet our 10Be sample selection criteria.

Figure 2Holocene moraine chronology of Jamtal. J0 (red) has been deposited after the LIA but prior to the 20th century (Fischer et al., 2019; K. u. k. Militärgeographisches Institut, 1870–1887). J1, J3R, and J4R were dated in this study. Ages along the J1 moraine (pink) indicate that Jamtalferner reached its historical maximum during the second half of the 18th century and during the Neoglacial (NG). Earlier phases of glacier stabilization that exceeded subsequent Holocene culminations are evidenced by moraines J3R and J4R, which both date to the EH. DEM provided by © Land Tirol (resolution 1 m).

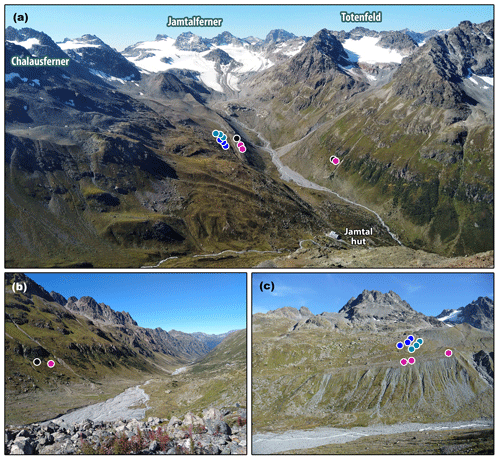

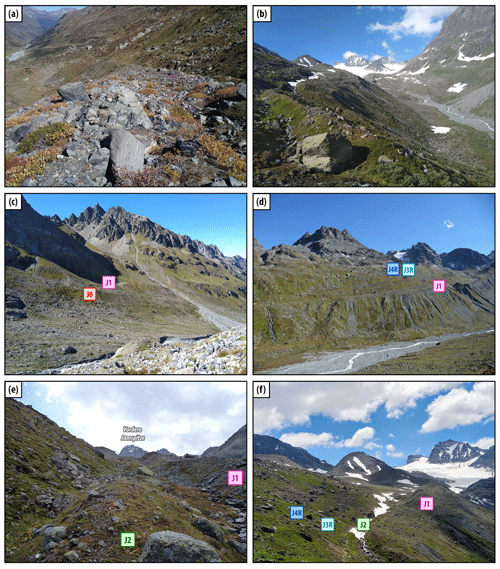

Figure 3Photographs of Jamtal. (a) View toward Jamtalferner and Totenfeld. 10Be sample locations are marked with colored circles (pink represents LIA; black represents Neoglacial, cyan and blue represent EH). (b) Down-valley view depicting sample locations JAM-18-06 (pink) and JAM-18-07 (black). (c) Valley flank below Chalausferner and Augustenferner with sampled boulders along the innermost (pink), middle (cyan), and outer (blue) right lateral moraine of former Chaulausferner. For the broader context of the individual sites, see Fig. 1c.

J3 and J4, two parallel, curved moraines about 20 to 30 m further uphill relative to J2, are right-lateral moraines of Chalausferner and evidence the convergence of this tributary glacier and the Jamtalferner (Fig. 3c). Boulder surfaces embedded in these moraines are populated with black and green lichens and show signs of weathering, for instance cracks and exfoliation. On the valley floor, a moraine with a frontal position at an altitude of about 2120 m a.s.l. is preserved. The ridge consists of weakly weathered material and is in this respect and with respect to geometry the terminal equivalent of the lateral J1 moraine (Figs. 2 and A2c). This correlation is in accordance with glacier outlines of the Austrian Glacier Inventory (AGI; Fischer et al., 2015), with a geomorphological map compiled by Hertl (2001, p. 226), and with results from a recent study on vegetation dynamics at the Jamtal, which includes ice margin reconstructions since the end of the LIA (Fischer et al., 2019). North of the terminal section of J1 is an area covered with angular and subangular blocks, whose surfaces are significantly more weathered compared to J1 and which exhibit extensive lichen population (Fig. A2c–e). Many blocks have cracks and are fractured, which may indicate impacts associated with gravitational movement. The morphology outboard J1 is convex – unusual for in situ rockfall deposits, which typically form lobate structures with large boulders in frontal positions. We therefore hypothesize that these deposits stem from rock failures along one (or both) valley flank(s) farther uphill. The material collapsed onto the formerly larger glacier and was transported downstream through glacial flow. As the glacier retreated, these rockfall deposits melted out and accumulated on the valley floor. An additional argument supporting this scenario is the provenance area of a potential rockfall event, which could not clearly be identified along the surrounding walls and peaks. The blockfield was in part overprinted by one (or multiple) glacier advances, as evidenced by the position of moraine J1.

A set of ridges in the right latero-frontal section outboard the J1 moraine appears to be somewhat displaced (Figs. 2 and A2f). A scarp above this moraine set and a stabilized sliding mass below caused an offset of formerly connected crests. Together with rockfall deposits from bedrock outcrops in higher-up sections, these moraines are not considered as prime candidates for 10Be sampling. We also avoided structures close to the Jamtal hut. Even though we identified several ridges in its vicinity, which were presumably deposited during the Holocene, land surfaces in this area have been anthropogenically altered. For instance, the road leading up to the hut and the hut itself are built on moraines (Hertl, 2001, p. 78). The same argument applies to a ridge at an elevation of approximately 2045 m a.s.l. denoted as J5 in (Figs. 2 and A2a–b). Although the structure may be interpreted as a Holocene terminal moraine, it was rejected for sample collection as it is in part anthropogenically overprinted and may comprise boulders disintegrated from the right-lateral slope above.

Evidence of older, LG terminal positions farther downstream is scarce. Hertl (2001, p. 77) describes a lineament that dips to the valley floor about 2.5 km downstream of J5, at an elevation of 1900–1920 m a.s.l. The author tentatively interprets the structure as a latero-frontal moraine deposited towards the YD termination. Around 8 km down valley from J5, a tripartite moraine set (Gaffelar settlement) is attributed to an earlier YD phase but not the YD maximum. Lateral LG moraines are absent in the main valley but are preserved in the Futschöl tributary valley, which joins the Jamtal from the east in the area of the Jamtal hut (Fig. 1b).

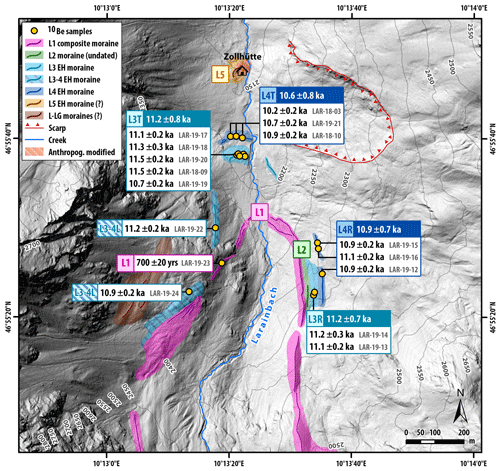

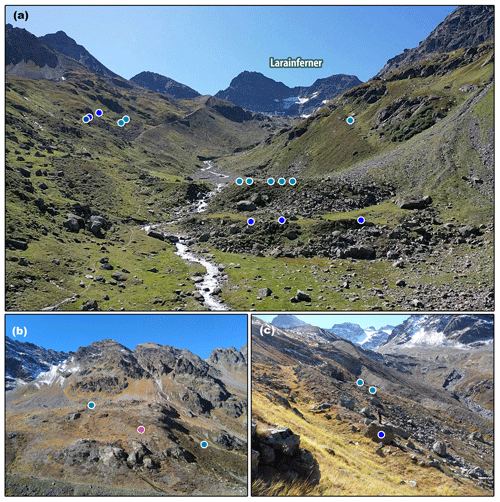

4.1.2 Laraintal

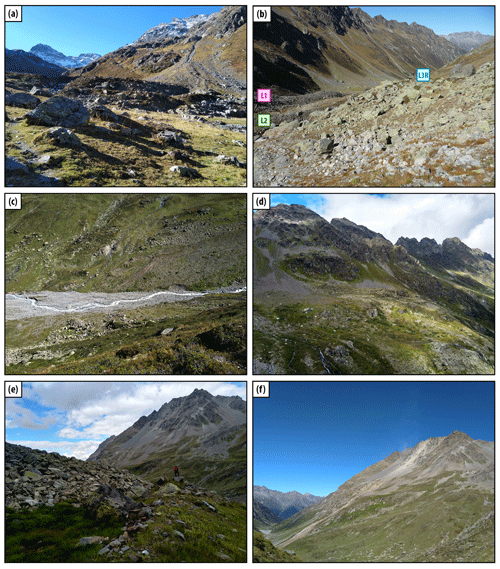

At Laraintal, we focused on valley sections outlined in Fig. 1d and detailed in Fig. 4. Texture, relative positions, and structure of moraines in this valley resemble moraine sets at the Jamtal. L1 – the presumable LIA ridge – consists of fresh, sparsely vegetated debris and is traceable along both valley flanks. On the eastern side, we identified a fine-structured set of moraines that we refer to as L2, L3R, and L4R in Fig. 4. Similar to J2, L2 with a width of approximately 8–10 m is less prominent compared to L1 (> 20 m; Fig. A3b). In addition, L2 has a high fine-sediment content with no large boulders on the crest. The fine-grained texture of L2 contrasts the subsequent outer L3R and L4R ridges, which are both blockier. The distinct nature of L2 (and also J2) in comparison with the outer moraines allows speculation about the different ice dynamics that led to their formation, for instance glacier advance (push moraine) versus glaciers in equilibrium (dump moraines). LR3 has a broader but less pronounced crest compared to LR4, the outermost moraine in this valley section (Fig. 5c). Boulders of both moraines, L3R and L4R, were sampled for 10Be extraction. Vegetation cover has developed on the surfaces of both ridges, and soil formation processes are advanced on the glacier-distal side of L4R.

Figure 4Holocene moraine chronology of Laraintal with moraine ages displayed. The 10Be sample collected from the L1 suggests an early LIA advance around 1300 CE. Lateral and terminal moraines outboard L1 yield EH ages, which agree well with the Jamtal moraine record. DEM provided by © Land Tirol (resolution 1 m; Land Tirol – tiris, 2018).

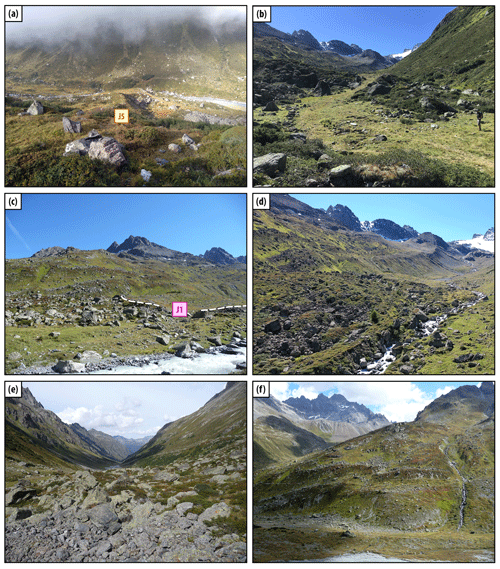

Figure 5Photographs of Laraintal. (a) Terminal moraine section with sample locations marked with circles. (b) Left lateral valley flank with LAR-19-22 (cyan), LAR-19-23 (pink), and LAR-19-22 (cyan) from left to right. (c) Right lateral moraine set with LAR-19-15 in blue in the foreground and LAR-19-13 and LAR-19-14 in the background (cyan). For the broader context of the individual sites, see Fig. 1d.

Analogous to the Jamtal, the terrain at the western valley side is generally steeper compared to the eastern side, with slope angles of ca. > 30∘. One exception is a riegel (bedrock bar) consisting of amphibolite that forms the basis for a relatively flat area (Fig. 5b and A3d). Geomorphology in this section has been influenced and shaped by debris flows, slope erosion, and the thawing of permafrost, in addition to glacial processes. Two ridges were deposited directly below the headwall amid a mix of scree, till, and rockfall deposits. According to Hertl (2001, p. 69), these ridges may mark late LG ice margins (Fig. 4) with a terminal equivalent around 4 km downstream at an elevation of ca. 1870 m a.s.l. In contrast to this complex section, ridges L1 and L3-4L farther away from the headwall and closer to the western edge of the riegel are well preserved and continue northwards and below the riegel. L3-4L can be traced along the valley flank until it is cut by a debris cone. L1 dips towards the valley floor, where its frontal segment splits up into at least two ridges. The area outboard the L1 terminus is covered with glaciofluvial sediments and is delimited by an arc-shaped blocky structure traversing the valley downstream at an altitude of ca. 2180 m a.s.l. (Fig. 5a, L3T). On the structure's glacier-proximal side, fine sediment has accumulated and gives this landform an almost terrace-like character with the blocky ridge acting as a barrier. The ridge is dissected by a creek (Larainbach); its western end is partly overburdened by the same debris cone, which cuts into L3-4L. Overall, the sedimentary composition, shape, and orientation of the ridge indicate that L3T is a moraine. An almost identical landform (L4T) replicates outside L3T at a horizontal distance of 50–60 m and with its crest at an elevation of about 2170 m a.s.l. (Fig. 5a). Both moraines (L3T and L4T) evidence former terminal positions of Larainferner and are correlated with lateral moraines L3-4L at the left-lateral side and with L3R and L4R at the right-lateral side.

Approximately 200–250 m further downstream, at an elevation of 2130 m a.s.l., is another set of ridges on one of which a small hut (“Zollhütte”) was built (Fig. 4). This Zollhütte ridge (L5) is framed by a blockfield consisting of a blend of angular and rounded boulders. A massive debris cone west of Zollhütte, which has a layer of coarse and medium-sized fresh material on top, points to continuous sediment supply from the left-lateral wall. To the east, a scarp with a concave surface below indicates former (and possibly ongoing) sliding processes directed towards Zollhütte. Moreover, rockfall events with material disintegrating from the wall below the “Hoher Kogel” peak have been witnessed during field work in the year 2019, with boulder volumes of multiple cubic meters that have crashed on the valley floor (Figs. 1d and A4a–b). Such events have probably also occurred in the past as the wall exhibits multiple lighter sections, which are indicative of removed material and thus of previous rock failures. Due to the manifold processes that impacted the Zollhütte area, the J5 ridge is scientifically risky to tackle with SED of boulders, even though it probably delimits a terminal glacier position.

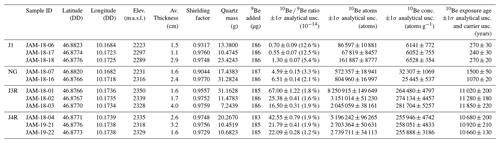

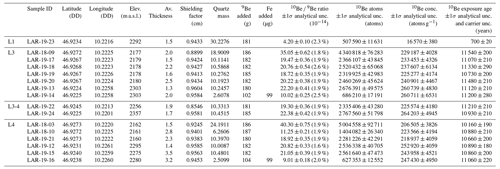

4.2 10Be results

10Be analytical data of all 27 boulder samples and corresponding age information are listed in Table 1 (Jamtal) and Table 2 (Laraintal). Kernel plots of moraine ages are displayed in Fig. 6 (LIA) and Fig. 7 (EH). Ages are reported for each valley individually and are discussed according to their landform number in ascending order, from J1 to J4 and from L1 to L4. All exposure ages fall into three periods of high(er) glacier activity within the past 12 kyr: the LIA, the first millennium CE, and the EH.

Table 110Be analytical data and corresponding exposure ages of Jamtal samples. Samples were analyzed at the CAMS-LLNL. All samples were measured against the 07KNSTD3110 standard with a ratio of 2.85 × 10−12 (Nishiizumi et al., 2007). Two procedural blanks were processed with each batch of samples with ratios ranging from 2.8 to 9.1 × 10−16 (Supplement Table S2). The10Be background contaminations measured in the blanks were subtracted from the samples. Exposure ages were calculated with the calculator formerly known as CRONUS-Earth online calculator (v3; Balco et al., 2008), using the Swiss 10Be production rate (Claude et al., 2014) and choosing the “Lm” scaling scheme. Ages are calculated relative to the sampling year, denoted by the first number in the sample ID, and are rounded to the nearest 10 years. Uncertainties of boulder ages include the 1σ analytical error and a 1 % uncertainty on the carrier concentration.

Table 210Be analytical data and corresponding exposure ages of Laraintal samples. For details on analytics, processing or age calculation see the captions of Tables 1, S1, and S2. Samples LAR-19-14 and LAR-19-16 were spiked with Fe in addition to (a reduced amount of) 9Be carrier.

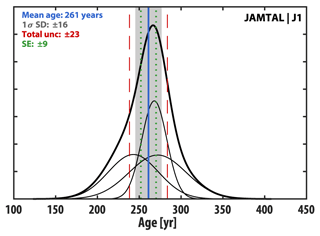

Figure 6Kernel plot of LIA ages produced from boulders embedded in the historical moraine at Jamtal. The gray-shaded bar illustrates the 1σ standard deviation (SD) of the landform age calculated from analytical uncertainties of individual samples. Dashed red lines add the production rate uncertainty and the uncertainty of the carrier concentration to the 1σ SD and indicate the total uncertainty. Dotted green lines show the standard error (SE), which describes the dispersion of different sample means from the population mean.

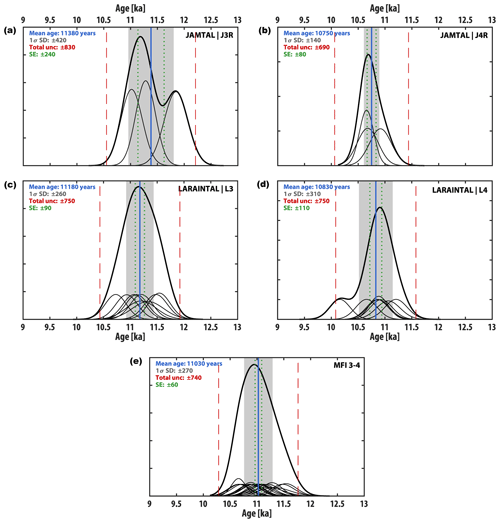

Figure 7Kernel plots of Holocene moraine ages. (a, c) Inner dated EH moraines at Jamtal and Laraintal. (b, d) Outermost dated EH moraines at Jamtal and Laraintal. (e) Synthesis of moraine ages across both valleys grouped into moraine formation intervals (MFI) MFI 3–4 yielding an age of 11 030 ± 740 years rounded to 11.0 ± 0.7 ka (n = 19; outliers: JAM-18-03 and LAR-18-03). Gray-shaded bars illustrate 1σ standard deviations (SDs) of landform age uncertainties calculated from analytical uncertainties of individual samples. Dashed red lines add the production rate uncertainty (ca. 6.3 %) and the uncertainty of the carrier concentration to the 1σ SD and indicate total uncertainties, which results in conservative uncertainty estimates. Dotted green lines indicate standard errors (SEs).

4.2.1 Jamtal

Five samples were collected from boulders along moraine J1 (Fig. 2, Table 1). Three of them (JAM-18-06, JAM-18-17, JAM-18-18) were deposited during the second half of the 18th century and yield a rounded mean age of 260 ± 20 years (Fig. 6). The other two samples, JAM-18-07 (1500 ± 50 years) and JAM-18-16 (1070 ± 20 years), both produce neoglacial ages. Since J2 lacks suitable boulders for 10Be sampling, the subsequent dated ridge is J3R. Based on three boulder ages of moraine J3R (JAM-18-01: 11,020 ± 200 years; JAM-18-02: 11 280 ± 180 years; JAM-18-03: 11,850 ± 220 years), we calculate a landform age of 11 380 ± 830 years, rounded to 11.4 ± 0.8 ka. J4R outside J3R gives a moraine age of 10 750 ± 690 years (10.8 ± 0.7 ka) derived from boulder ages of samples JAM-18-04 (10 680 ± 200 years), JAM-19-21 (10 920 ± 210 years), and JAM-19-22 (10 660 ± 130 years) (Fig. 7a–b).

4.2.2 Laraintal

Sample LAR-19-23 (700 ± 20 years) stems from L1 and might capture a LIA maximum early in the 14th century (Fig. 4, Table 2). The deposition of the left-lateral L3-4L moraine is constrained by LAR-19-22 with a boulder age of 11 210 ± 210 years and by LAR-19-24 dated to 10 930 ± 210 years. These ages are statistically indistinguishable and cannot clearly be assigned to either the inner moraine (L3) or the outer one (L4). Therefore, they are included in landform age calculations of both ridges. The right-lateral L3R ridge yields boulder ages of 11 120 ± 210 years (LAR-19-13) and 11 200 ± 280 years (LAR-19-14). The age of the terminal segment of L3-4L – L3T – is derived from samples LAR-18-09 (11 540 ± 200 years), LAR-19-17 (11 070 ± 210 years), LAR-19-18 (11 330 ± 290 years), LAR-19-19 (10 730 ± 200 years), LAR-19-20 (11 480 ± 210 years) and results in a landform age of 11 230 ± 780 years. Based on our mapping and dating results, we are confident that moraine segments L3R and L3T and potentially L3-4L can be attributed to the same glacier advance or stabilization. Therefore, we aggregate all nine boulder ages and compute a moraine age of 11 180 ± 750 years (L3: 11.2 ± 0.8 ka; Fig. 7c). Based on the same reasoning, we combine L3-4L, L4R (LAR-19-12: 10 890 ± 180 years; LAR-19-15: 10 860 ± 200 years; LAR-19-16: 11 060 ± 220 years; landform age 10 940 ± 690 years), and L4T (LAR-18-03: 10 160 ± 190 years; LAR-18-10: 10 880 ± 210 years; LAR-19-21: 10 660 ± 200 years; landform age 10 570 ± 760 years) and suggest a moraine age of 10 830 ± 750 years (L4: 10.8 ± 0.8 ka; Fig. 7d).

Analytical results from samples, which were spiked with Fe, show that ages calculated from both samples are consistent with boulder ages obtained for the same landforms but processed according to the standard protocol (L3R: LAR-19-13; L4R: LAR-19-12 and LAR-19-15). Analytical uncertainties of corresponding samples amount to 2.0 % (LAR-19-16) and 2.5 % (LAR-19-14) and are within the expected range of 10Be AMS measurement uncertainties at LLNL-CAMS (Rood et al., 2013). By replacing a portion of the 9Be carrier with Fe, we achieved similar analytical precision as with routinely processed samples but with only a quarter of the sample mass used. Our results suggest that the substitution of a fraction of 9Be carrier using Fe is a viable and promising advancement in the sample preparation protocol that extends the application field of the 10Be SED method to younger samples and more challenging lithologies.

5.1 The moraine record of the past two millennia

The classical LIA moraines of both valleys (J1 and L1) feature boulders deposited within the expected time interval, i.e. between 1250 and 1850 CE (Fig. 8f; e.g., Grove, 2004; PAGES 2k Consortium, 2013). An early LIA advance of Larainferner to L1's position is suggested by LAR-19-23 and may have occurred at the beginning of the 14th century. Three consistent boulder ages from J1 are aggregated to a mean age of 260 ± 20 years and indicate an advance of Jamtalferner between ca. 1735 and 1790 CE. A recent geochronological study in the adjacent Ochsental comes to remarkably similar results, with boulder ages from the LIA moraine yielding a mean age of 260 ± 30 years (Fig. 8e; Braumann et al., 2020). Glacier advances during this period are also documented in the Eastern Alps, for instance at the Zillertal and at the Ötztal (Nicolussi, 2013; Pindur and Heuberger, 2010), in the Central Alps at the Lower Grindelwald glacier (Zumbühl and Nussbaumer, 2018), and in the Western Alps at the Mer de Glace (Nussbaumer et al., 2007). High glacial activity during the second half of the 18th century with termini coming close to or reaching their LIA maximum is congruent with a phase of decreased summer temperatures detected in proxy records in the vicinity of our study site (Fig. 8a–b; Fohlmeister et al., 2013; Ilyashuk et al., 2019; Larocque-Tobler et al., 2010a; Vollweiler et al., 2006) and with reconstructed summer and mean annual temperatures from Greenland ice cores (Fig. 8d; Buizert et al., 2018; Kobashi et al., 2017).

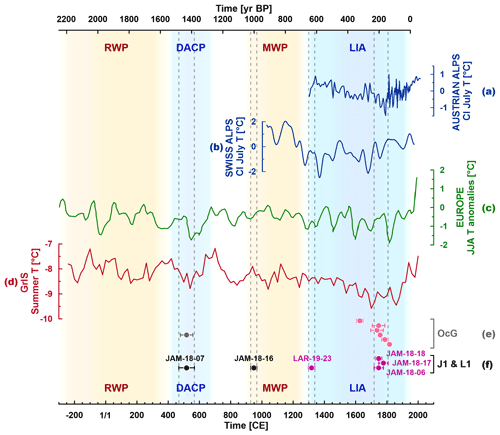

Figure 8The youngest part of the 10Be chronology from Jamtal and Laraintal correlated with climate proxy data from the Alps (local records in dark blue), Europe (green), and the Greenland Ice Sheet (GrIS in red) covering the past ca. 2000 years. Proxy records indicate cooler climate conditions during the Dark Ages Cold Period (DACP) and during the Little Ice Age (LIA), synchronous with periods of moraine formation in the Silvretta region. Chironomid-inferred (CI) July temperatures from (a) Mutterbergersee in the Stubai Alps, Austria (Ilyashuk et al., 2019), approximately 70 km east of study site (north of the Alpine drainage divide) and (b) lake Silvaplana, around 60 km southwest of study site (Engadin, Switzerland; south of the Alpine drainage divide) (Larocque-Tobler et al., 2010a). (c) European summer temperature anomalies (reference period 1961–1990, 60-year low-pass filter) identified in tree-ring chronologies (Büntgen et al., 2011). (d) Mean summer temperature reconstructions (JJA) derived from nine Greenland ice cores (Buizert et al., 2018). (e) 10Be ages of boulders sampled from the presumable LIA (Holocene composite moraine) from Ochsental (OcG) (Braumann et al., 2020) and from (f) Jamtal and Laraintal (this study). RWP stands for Roman Warm Period, and MWP stands for Medieval Warm Period.

Besides LIA-aged boulders along the LIA moraine, we sampled two blocks of J1 that were deposited during the first millennium of the Common Era. The younger boulder, JAM-18-16, dates to the beginning of the Medieval Warm Period (MWP). By that time, glaciers in the region were likely smaller relative to their LIA maxima (e.g., Solomina et al., 2016). The boulder's position and its bedding were re-evaluated in the field after age calculation, and we cannot exclude that the boulder has tilted (Fig. S7). Therefore, we interpret the exposure age as a minimum age. The older neoglacial boulder, JAM-18-07, was exposed 1500 ± 50 years ago, which is again in good agreement with the neighboring Ochsental chronology, where a block in an identical setting (embedded in the classical LIA moraine) was dated to 1500 ± 40 years (Fig. 8e; Braumann et al., 2020). There is a possibility of pre-exposure of both samples that could produce erroneous Neoglacial ages. However, evidence for a period of glacier advance in the Eastern Alps during the 5th and 6th centuries CE was found beyond the Silvretta region, for instance in sediment profiles and peat cores in the forefield of Fernauferner, Mittelbergferner, and Simonykees (Patzelt, 2016; Patzelt and Bortenschlager, 1973). This timing coincides with prominent episodes of glacier advance in the Western Alps, most notably at the Aletsch glacier (Holzhauser et al., 2005) and at the Miage and Mer de Glace, both in the Mont Blanc massif (Deline and Orombelli, 2005; Le Roy et al., 2015). Concurrent glacier advances have also been reported from Alaska, Iceland, Scandinavia, and Greenland (Barclay et al., 2009; Biette et al., 2020; Solomina et al., 2016). Glacier advance during this period is consistent with decreasing summer temperatures (Fig. 8c–d) and higher precipitation rates in Europe (e.g., Büntgen et al., 2011). This regional climate perturbation, which is often referred to as Dark Ages Cold Period (DACP) and occurred in tandem with the migration period in Europe, began around 400 CE and lasted into the 8th century CE in the region (e.g., Helama et al., 2017). During that time, the Atlantic meridional overturning circulation (AMOC), which transports heat from the South Atlantic towards the north, was weakened (Thornalley et al., 2018), which led to cooling in the Nordic region. Potential volcanic eruption(s) in the Northern Hemisphere in the year 536 CE may have amplified cooling across Europe and defined the onset of the recently postulated Late Antique Little Ice Age (LALIA; 536 to ca. 660 CE; Büntgen et al., 2016). Consistent with the timing of the regional DACP, Helama et al. (2021) suggests centennial-scale phases in Northern Europe during the Holocene that resemble the LIA climatic regime, with one of them beginning around 540 CE.

In summary, samples collected along the classical LIA moraine at the Jamtal (this study) and at the adjacent Ochsental (Braumann et al., 2020) yield ages that fall into the regional DACP and the LIA. These results are consistent with the timing of glacier advances across the Alps and in other places of the Northern Hemisphere. The advance of Silvretta glaciers coincides with cooling trends captured in local, regional, and hemispheric proxy data. Moraines J1 and L1 are probably composite moraines that have represented ice margins at least once prior to the LIA. J1 and L1, in the following sections termed “Holocene composite moraines”, mark the maximum of glacier advances and corresponding temperature minima since the end of the YD–EH transition.

5.2 The moraine record of the early Holocene

5.2.1 Local correlation

Moraine records at Jamtal and at Laraintal are remarkably similar and point to synchronous glacier dynamics throughout the Holocene, particularly during its onset. In both valleys, we identified up to three lateral ridges just outboard the J1 and L1 composite moraines and their terminal equivalents, albeit in varying states of preservation. The outermost ridges in both valleys, J3R and L3, and J4R and L4, respectively, yield statistically identical landform ages (Fig. 7a–d). Interestingly, they are chronostratigraphically inverse, i.e., JR3 and L3 are systematically several centuries older than JR4 and L4. An explanation for this age pattern may be decadal- to centennial-scale pre-exposure of J3R and L3 boulders, which would lead to an overestimation of ages. However, if pre-exposure was a problem in the data set, we would expect greater scatter in boulder ages inferred for the same moraine. Another explanation for age inversion is post-depositional displacement such as sacking or tilting of J4R and L4 boulders, for instance through the thawing of permafrost, which would lead to underestimation of corresponding ages. Yet again boulder ages along JR4 and L4 are in good agreement, making this explanation unlikely. A process, which may have affected JR4 and L4 boulder surfaces and could cause a systematic shift towards younger ages, is katabatic winds, when the glacier abandoned moraines JR4 and L4 and halted for a few centuries at the positions of or close to JR3 and L3. Consolidation of the age difference between moraines JR3/L3 and J4R/L4 would necessitate the removal of approximately 2.5 mm of rock from boulder surfaces along the outermost moraines (J4R and L4) within 500 years.

The age pattern of EH moraines in the Jamtal and Laraintal is noteworthy, but we emphasize that moraine ages of JR3, L3, JR4, and L4 overlap within 1σ uncertainties and that age inversion is non-existent from a statistical point of view. As we attribute the landforms to a climatic state, we group them across both valleys and refer to them as moraine formation intervals (MFI) 3–4, equivalent to 11 030 ± 740 years, rounded to 11.0 ± 0.7 ka (Fig. 7f).

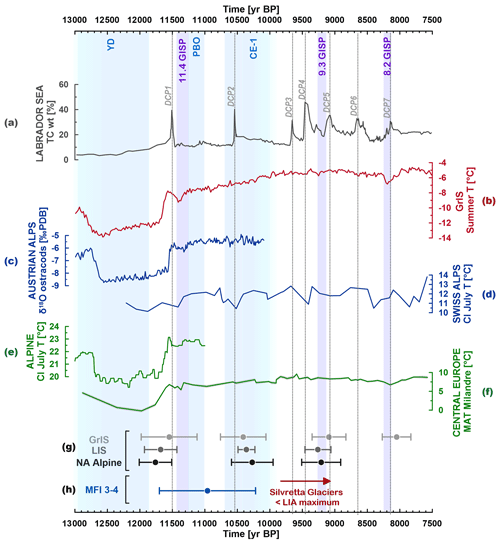

Figure 9Proxy records capturing the YD-EH transition. (a) Detrital Carbonate Peaks (DCPs) identified in marine sediment cores from the Labrador Sea (Jennings et al., 2015); TC stands for total carbonate. (b) Mean summer temperature reconstructions (JJA) derived from nine Greenland ice cores (Buizert et al., 2018). (c) Ostracods record extracted from lake sediments of Mondsee (Austrian Alps) (Lauterbach et al., 2011). (d) Chironomid-inferred (CI) atmospheric July temperatures from lake sediments of Hinterburgsee in the Swiss Alps. (e) Stacked CI July temperatures in the European Alps (Heiri et al., 2014). (f) Mean annual temperatures (MATs) in central Europe reconstructed based on speleothems from Milandre Cave, Switzerland (Affolter et al., 2019). (g) Arctic moraine record: GrIS indicates Greenland Ice Sheet moraines, LIS indicates Laurentide Ice Sheet (LIS) moraines, and NA Alpine indicates North American Alpine mountain glacier moraines (Young et al., 2020). (h) Moraine formation intervals (MFI) identified in this study. Purple bars highlight Holocene cold events detected in Greenland ice cores (Rasmussen et al., 2007).

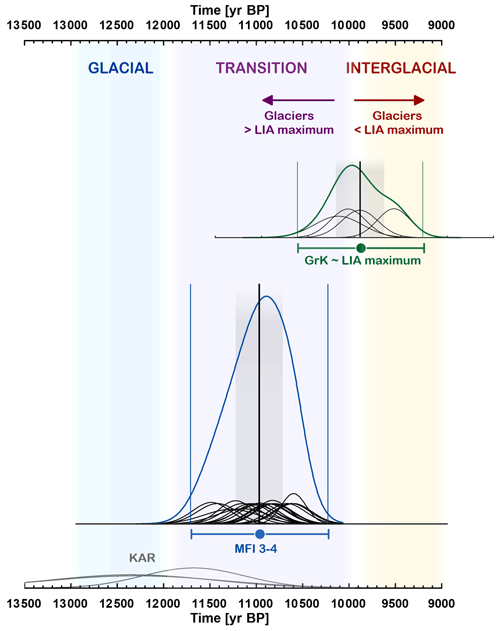

We correlate EH Jamtal and Laraintal moraine chronologies with moraine chronologies and glacier proxy records at the local scale and propose a concept of YD–EH deglaciation. MFI 3–4 falls well into the EH and is different from advances during the LG. Presumable YD moraines are identified at considerable distance downstream and outboard of landforms addressed in this study (Hertl, 2001, pp. 220 and 225), which implies that glaciers shrank from their LG ice margin to a position close to the LIA maximum within a few centuries. Rapid deglaciation is a direct response of glaciers to an increase of summer temperatures by several degrees during the YD–EH transition in the eastern Alpine region and across the Alps (Fig. 9c–f; e.g., Affolter et al., 2019; Heiri et al., 2014; Ilyashuk et al., 2009; Larocque-Tobler et al., 2010b; Samartin et al., 2012). This warming trend was interrupted by brief cold spells, which manifest in moraine records in the Silvretta Massif and in the adjacent Verwall mountains to the northeast. Based on these moraine chronologies, the following local YD–EH glacier history emerges (Fig. 10).

- i.

Latest YD – Kartell moraines (Verwall).

Moraines that formed within this period in the region have been dated at the Kartell site, which is around 15–20 km northeast of Jamtal and Laraintal (Ivy-Ochs et al., 2006). Because of the previously higher 10Be production rate estimate, Kartell moraines were initially placed into the EH. Recalculations using the updated production rate yield boulder ages ranging between 11.8 ± 0.6 and 12.5 ± 0.9 ka with the production rate uncertainty excluded. The age update now assigns Kartell moraines to the late(st) YD (Boxleitner et al., 2019b; Ivy-Ochs, 2015). A local lowering of the ELA of approximately 110–120 m relative to the historical moraine that was calculated using the accumulation area ratio (AAR) method (Gross et al., 1978), was reported by Sailer and Kerschner (1999) and Ivy-Ochs et al. (2006).

- ii.

YD–EH transition (Preboreal) – MFI 3–4.

The shift from glacial to interglacial conditions is captured at the Jamtal and Laraintal. Corresponding moraine chronologies indicate ice margins at terminal positions some hundreds of meters outboard of the LIA maximum, equivalent to an estimated ELA depression of approximately 70 m (AAR method; Hertl, 2001, p. 80). These chronologies evidence abrupt cold snaps, which punctuated the general warming trend during the EH and which caused decadal- to centennial-scale glacier oscillations. The mean age of MFI 3–4 (11.0 ± 0.7 ka) follows the Preboreal oscillation (PBO) as defined based on paleoenvironmental records from Europe (11.30–11.15 ka; e.g., Bjorck et al., 1997; Joannin et al., 2013; Magny et al., 2007; Schwander et al., 2000). Evidence of subsequent summer cooling between 10 700 and 10 500 cal BP is detected in lake sediments in the Swiss and Austrian Alps (Fig. 9c–d; Heiri et al., 2003; Lauterbach et al., 2011).

Kromer moraines identified in valleys 10–15 km further towards the west (Fig. 1b) were originally placed into the Preboreal (Gross et al., 1978). Morphologically, these moraines resemble the blocky, multi-ridge structures of J3R and J4R at the Jamtal and L3 and L4 at the Laraintal and yield similar snowline depression estimates of 70–90 m. Updated 10Be moraine ages of 9.9 ± 0.7 and 10.2 ± 0.7 ka fall within a somewhat younger age spectrum compared to the Jamtal and Laraintal moraines (Kerschner et al., 2006; Moran et al., 2016b). However, the age discrepancy between Kromer moraines and Jamtal and Laraintal moraines could be reconciled considering age uncertainties.

- iii.

Interglacial (Holocene) mode – Ochsental–Grüne Kuppe (GrK).

Deglaciation patterns in the Ochsental to the west suggest ice margin configurations similar to the LIA around 10 ka. The timing of moraine formation adjacent to the lateral Holocene composite moraine (equivalent to J1 and L1 in this study) was constrained to 9.9 ± 0.7 ka (Grüne Kuppe site, n = 4) (Braumann et al., 2020). In addition, two boulders of the same age were found in latero-frontal sections of the Holocene composite moraine and point to similar ice margins around 10 ka and during the LIA. Although no exposure ages are available for J2 and L2, and despite the fact that these moraines could have been deposited within any cold phase between MFI 3–4 and the LIA, we note that J2 and L2 potentially may correlate with the Grüne Kuppe moraine, particularly as the ridges are in a morphostratigraphically similar position. The timing of the Grüne Kuppe moraine stabilization aligns with a climate anomaly detected in some proxy records of the Alps around 10.5 ka that persisted for several centuries, sometimes termed the central European cold phase 1 (CE-1; e.g., Boch et al., 2009; Haas et al., 1998; Schmidt et al., 2006). This phase was followed by deglaciation, and glaciers in the Alps receded to sizes smaller than their historical maximum (Patzelt, 2019; Solomina et al., 2015). Glacier retreat led to a vegetation change, with trees spreading to high(er) elevations. At the Las Gondas bog in the adjacent Fimbatal (Fig. 1b), subfossil wood and tree logs were found up to an elevation of 2370 m a.s.l., with the oldest sample dated to 8620–8480 cal BP at 2355 m a.s.l. (Nicolussi, 2010). In close vicinity to our study sites (Futschöltal), evidence of Pinus cembra populations growing at an elevation of ca. 2290 m a.s.l. within the period between ca. 5580 and 4970 cal BP was found (Patzelt, 2019). Consistent results were reported from other valleys in the region, for instance from the Klostertal and the Bielerhöhe sites (Nicolussi, 2010), and from Kaunertal (Nicolussi et al., 2005) (Fig. 1b).

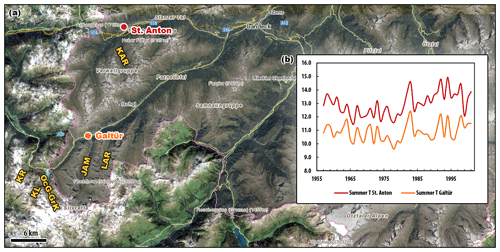

The timing of moraine formation at the Kartell site overlaps with MFI 3–4, just as MFI 3–4 overlaps with moraine formation at GrK in the Ochsental. Instead of indicating individual phases of glacier advance or stabilization, differences in the landforms' central ages could also be owed to uncertainties of the dating method, which we cannot exclude, or to catchment-specific effects such as shading or bedrock topography. We note that catchments where the evaluated 10Be moraine chronologies were generated are comparable in terms of elevation, glacier size, exposure, geographical location (north of the Alpine drainage divide), and orientation (Fig. B1a). Furthermore, summer temperature time series of meteorological stations at St. Anton in the Verwall region and at Galtür in the Silvretta region show similar trends in the period from 1957 to 2001 (Fig. B1b). We assume that glaciers in the region respond(ed) to the same temperature forcing and probably at a similar level of sensitivity not only in recent decades but also before then. Hence, the multiphase age structure of EH moraine formation in the Verwall and Silvretta regions points to distinct episodes of glacier advance or stabilization.

Figure 10Glacier retreat during the transition from glacial to interglacial conditions evidenced in moraine chronologies from the Silvretta and Verwall regions. KAR indicates Kartell moraines (Ivy-Ochs, 2015; Ivy-Ochs et al., 2006). The site is located approximately 15–20 km northeast of Jamtal and Laraintal. MFI 3–4 are as described in this study. GrK indicates the Grüne Kuppe moraine identified in the adjacent Ochsental, suggesting LIA-like glacier extents around 10 000 cal BP (Braumann et al., 2020).

5.2.2 Alpine-wide and hemispheric correlation

Moraine formation during the transition from glacial to interglacial climatic conditions that is presented in Fig. 10 builds on glacier records in the Silvretta Massif and in the Verwall mountains in the Eastern Alps. This model is consistent with results of previous studies that have addressed glacier evolution during the LG and EH based on moraine chronologies (e.g., Baroni et al., 2017; Hofmann et al., 2019; Moran et al., 2016a, 2017; Protin et al., 2021, 2019; Schimmelpfennig et al., 2012, 2014; Schindelwig et al., 2012). Investigated moraine sets may differ with respect to their structure, state of preservation, or distance relative to the LIA maximum, but they share their position (outboard the LIA maximum but inboard the presumable LG ice margin) and their age of deposition between ca. 12 and 10 ka, which implies substantial large-scale cooling during this period. This pattern of EH moraine stabilization is not limited to the Alpine realm but has been observed in other places in the North Atlantic and Arctic region, for instance along the Fennoscandian ice sheet (e.g., Briner et al., 2014; Nesje, 2009), the Icelandic ice sheet (e.g., Sigfusdottir and Benediktsson, 2020), at Svalbard (e.g., Farnsworth et al., 2020), along the eastern part of the LIS (e.g., Corbett et al., 2016; Ullman et al., 2016; Young et al., 2020), and along the Greenland ice sheet (e.g., Biette et al., 2020; Levy et al., 2016; Young et al., 2020) (Fig. 9g). Atmospheric temperatures were certainly different in these regions during the EH (Fig. 9b–f), and glaciers in the European Alps retreated much earlier to positions inboard their subsequent historical margin compared to Arctic glaciers, which continued to deposit moraines outboard their LIA at least 2 millennia longer. However, concurrent moraine stabilization during the EH raises the question what caused this synchronicity in climatic cooling during the first millennia of the Holocene.

5.2.3 Climatic drivers of EH moraine formation in the Northern Hemisphere

Freshwater influx into the North Atlantic and into the Arctic Ocean is known as a driver for climate of the Northern Hemisphere and acts as a plausible cause for abrupt centennial-scale cold snaps during the LG and the EH (e.g., Bjorck et al., 1997; Fisher et al., 2002; Hald and Hagen, 1998; Nesje et al., 2004). Prominent examples are repeated outbursts of the North American proglacial Agassiz lake, whose final drainage caused a sharp temperature drop in the Northern Hemisphere, the 8.2 ka event detected in Greenland ice cores (Alley and Agustsdottir, 2005; Clarke et al., 2009; Hillaire-Marcel et al., 2007; Teller et al., 2002; Thornalley et al., 2010). Besides abrupt high-volume releases of freshwater to the North Atlantic or Arctic Ocean via major lake drainages or iceberg armadas, there is evidence of more subdued glacial discharge during the EH that results in a deceleration of the thermohaline circulation (Bamberg et al., 2010; Renssen et al., 2010; Thornalley et al., 2009). Weakening of the AMOC leads to less heat transported to the North Atlantic region, which can prompt brief decadal-to-centennial-scale cold snaps in the north and also at lower latitudes. During the PBO and subsequent centennial-scale cold phases, harsher climate conditions are reported in the North Atlantic region (e.g., Bos et al., 2007; Knudsen et al., 2008; Paus et al., 2015; Timms et al., 2021), with cooling extending towards western and central Europe (Fig. 9c–f). Glaciers in North Atlantic regions and in the Alps responded to these climate perturbations with stabilization or advance and hence moraine deposition.

To test the linkage between EH moraine formation and freshwater discharge of the LIS, we review corresponding markers in marine sediment cores, temperature proxy records, and moraine records in these regions. We begin with the YD termination, when icebergs and meltwater plumes were released into the North Atlantic, evidenced by ice-rafted debris and layers of “foreign” sediment enriched with detrital carbonates in marine sediments. These layers, often referred to as Heinrich-0 (H0) and characterized by a detrital carbonate peak (DCP) date to the earliest Holocene, were identified in Baffin Bay (Simon et al., 2014), in the Labrador Sea (Andrews et al., 1995; Rashid et al., 2011), and at the coast of Newfoundland (Pearce et al., 2015) including the Flemish cap (Li and Piper, 2015). Jennings et al. (2015) found multiple subsequent detrital carbonate peaks (DCP 1–7 in Fig. 9a) between 11 500 and 8000 cal BP in a core from the Labrador shelf, which is attributed to freshwater sourced from Hudson Strait. DCP1 detected around 11 500 cal BP coincides with the end of H0 and with the onset of 11.4 ka event (ca. 11 450 to 11 350 cal BP; Rasmussen et al., 2007). During the subsequent PBO captured in Nordic records, mean annual and summer temperatures in the European Alps declined (Fig. 9e–f; e.g., Affolter et al., 2019; Heiri et al., 2014; Lauterbach et al., 2011). The propagation of this cooling trend towards western and central Europe is supported by cooler and more humid climate conditions in these regions ca. 11 300–11 150 cal BP (Magny et al., 2007). In parallel, 10Be concentration in Greenland ice cores, a proxy for solar activity, decreases towards a minimum (Adolphi et al., 2014; Finkel and Nishiizumi, 1997; Mekhaldi et al., 2020). Low solar activity may have amplified the cooling imposed by freshening of the Atlantic Ocean or vice versa. Glaciers in the North Atlantic region and in the European Alps advanced or stabilized repeatedly during the first millennia of the Holocene and deposited moraines, as evidenced by landforms dated in this study (Fig. 9h).

A similar chain of events may have occurred some centuries later. The deposition of the DCP2 ca. 10 600 cal BP was preceded by the so-called Gold Cove advance of the LIS's Labrador sector across the Hudson Strait and its subsequent retreat (Jennings et al., 2015; Kaufman et al., 1993; Rashid et al., 2014). The resulting freshwater input may have weakened the AMOC, which in turn led to a drop in mean annual temperatures in Greenland and moraine formation in the Arctic (e.g., Biette et al., 2020; Young et al., 2020). Temperatures in the Alps decreased or stagnated around that time (Fig. 9c–d, f). Moraine formation between 10 700 and 10 500 cal BP, concurrent with DCP2, is observed across the European Alps (e.g., Moran et al., 2017; Protin et al., 2019; Schimmelpfennig et al., 2012, 2014).

The linkage between DCPs, freshwater input into the Atlantic and Arctic Ocean, and subsequent EH glacier advances has been put forward before in the context of the North American and Arctic region (e.g., Andrews et al., 2014; Nesje, 2009; Young et al., 2020). The authors of a recent geochronological study carried out in the Western Alps go a step further and propose that freshwater forcing in the North Atlantic region acted as a driver for moraine formation in the Mont Blanc Massif (Protin et al., 2021). They suggest that a decrease in AMOC strength led to extended sea ice periods during winter in the North Atlantic, which in turn caused a southwards shift of the westerlies. Cold air was then transported to Europe and led to moraine deposition in the European Alps. With our new moraine chronologies from the Silvretta region, we complement the glacier record from the Western Alps with robust evidence for EH moraine formation in the Eastern Alps and corroborate the hypothesis that centennial-scale cold phases occurred at a regional (hemispheric) scale between 12 and 10 ka.

-

Glaciers at both study sites, the Jamtal and the Laraintal, stabilized or advanced at least twice during the EH, which is evidenced by moraines deposited outboard the historical moraine (LIA maximum) and inboard the presumable LG ice margin. The timing of moraine formation is consistent across both valleys and is constrained with 10Be SED, yielding a combined age of 11.0 ± 0.7 ka (MFI 3–4, n = 19). EH moraines in the Silvretta region indicate repeated punctuation of the general postglacial warming trend by short cold episodes in Europe. These cold snaps, most prominently the PBO, appear to have their origin in the North Atlantic region. Layers of ice-rafted debris and DCPs in marine sediment cores along the eastern margin of the LIS point to glacial discharge during the earliest Holocene. Resulting freshwater released into the North Atlantic probably caused a drop in salinity and led to a slowdown of the AMOC. Reduced heat transport northwards caused cooling in the North Atlantic region, which propagated toward Europe. Glaciers and ice sheets in the Northern Hemisphere responded to this cooling via moraine deposition.

-

Based on Holocene moraine chronologies of the Silvretta Massif and the adjacent Verwall mountains, we propose the following local model that describes alternating phases of glacier retreat and stabilization between 12 and 10 ka: the YD termination (Kartell; Ivy-Ochs, 2015; Ivy-Ochs et al., 2006), the YD–EH transition (MFI 3–4, this study), and the Holocene mode (GrK; Braumann et al., 2020). The proposed concept confirms the hypothesis formulated by Patzelt and Bortenschlager (1973) almost 50 years ago that glaciers in the Eastern Alps deposited moraines during the Preboreal and had retreated to their subsequent historical ice margins by ca. 10 to 9.5 ka. During the rest of the Holocene, the magnitude of cooling was most likely too small in the Eastern Alps to force advances which exceeded dimensions that glaciers had around 10 ka.

-

Our data suggests that glaciers in the Silvretta region advanced to a position close or equivalent to their LIA maximum around 500 CE. The timing of this advance is concurrent with the migration period in Europe, which is often associated with regional climate deterioration. In the Silvretta Massif, this hypothesis rests on a few 10Be exposure ages of the Jamtal (this study) and the Ochsental (Braumann et al., 2020), but there is growing evidence that many glaciers in the Alps, North America, and the Nordic region advanced at that time and reached their historical margin (e.g., Barclay et al., 2009; Holzhauser et al., 2005; Le Roy et al., 2015; Patzelt, 2016).

-

Silvretta glaciers may have advanced to their LIA maximum as early as ca. 1300 CE. A subsequent advance to the same position took place in the second half of the 18th century, documented by three boulders along the historic moraine yielding a mean age of ca. 260 ± 20 years. This result agrees well with an advance of glaciers in the adjacent Ochsental (Braumann et al., 2020). Contemporaneous advances have also been reported for glaciated areas beyond the Silvretta region, e.g., the Lower Grindelwald glacier, Mer de Glace, and glaciers in the Ötztal (Nicolussi, 2013; Nussbaumer et al., 2007; Pindur and Heuberger, 2010; Zumbühl and Nussbaumer, 2018).

-

The classical LIA moraine in the European Alps, traditionally referred to as the “1850 moraine”, marks the LIA maximum glacier extent that was reached multiple times during the LIA but perhaps also earlier during the Holocene, most likely around 500 CE. As the moraine comprises glacial sediments deposited during several glacier advances during the past millennia, we propose that these landforms should rather be viewed as “Holocene composite moraines” instead of “1850 moraines” or “LIA moraines”.

-

Our observations document sensitive glacier response to the natural warming in the early Holocene. Accelerating anthropogenic warming has been driving the rapid retreat of highly temperature-sensitive glaciers over the last century (e.g., Oerlemans, 2005; Zemp et al., 2019) and will lead to the disappearance of most glaciers in the European Alps unless greenhouse gas forcing is substantially reduced in the very near future (Zekollari et al., 2019).

Figure A1Jamtal. (a) J1 moraine with Jamtal hut in the background. Boulder surfaces are fresh and are not colonized by lichens; pioneer plants are growing on the moraine. (b) J1 multi-ridge structure with view towards with Jamtalferner in the back. (c) Left-lateral side of Jamtal below Totenfeld glacier. (d) View towards Chalausferner (in the background); J1 is in the foreground, J3R and J4R outboard J1 are curved lateral moraines of former Chalausferner. (e) J2 moraine (undated) is at the center with a till-covered slope to the left and J1 to the right. (f) Right-lateral moraine sets. J4R and J3R date to the early Holocene, and J1 is comprised of debris that was deposited during the LIA and during at least one earlier glacier advance around 500 CE.

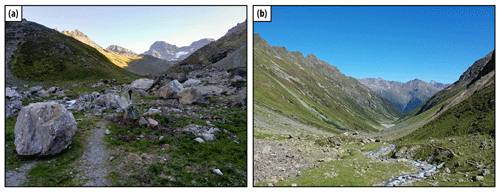

Figure A2Jamtal. (a) J5 ridge view from right-lateral valley side towards the west and a (b) view from a down-valley position southwards. The structure was reworked in the course of trail construction and maintenance. (c) Transition zone between J1 terminal moraine and the blockfield. We speculate that the blockfield originates from rock failures along valley flanks farther up valley. Corresponding debris was transported downstream by the glacier. During glacier retreat, the blocks melted out and covered the valley floor. The blockfield (at least its uppermost section) was then partly overprinted by subsequent glacier advances. (d) Blockfield consisting of coarse, angular to subangular components with a view towards the southeast. (e) Transition zone between fresh J1 moraine deposits and the blockfield, whose blocks are populated by lichens and are partly overgrown with vegetation. (f) Displaced moraines along the right-lateral valley side outboard J1; Futschöltal (tributary valley) is shown in the back.

Figure A3Laraintal. (a) Terminal moraines L3T and L4T dissected by a creek (Larainbach). (b) Right-lateral moraine set: L1, L2 (undated), and L3R. (c) Larainbach, with the modern river plane with L1 double-ridge structure identified on both sides of the creek. (d) Left-lateral flatter valley section, where moraines L3L and L1 and presumably Late Glacial moraines accumulated. (e) Left-lateral glacier side. Person standing on L1 ridge with L3L to the left. Hoher Kogel peak is in the background. (f) Provenance area of the rockfall event in 2019 near Hoher Kogel peak.

Figure A4Laraintal. (a) Fresh rockfall deposits (2019) in the Zollhütte area. Note the person at the center of the photograph for scale. (b) Zollhütte area (L5) with unweathered scree on the left side of the photograph, a mass movement slab to the right of the hiking trail, and fresh rockfall path behind the slab.

Figure B1Overview of Silvretta and Verwall regions addressed in local correlation of moraine records (Sect. 5.2.1). (a) 10Be moraine records generated in the following valleys: KAR is Kartell (Ivy-Ochs et al., 2006), KL is Klostertal, KR is Kromertal (Moran et al., 2016b), OcG-GrK is Ochsental/Grüne Kuppe (Braumann et al., 2020), JAM is Jamtal, and LAR is Laraintal (this study). Locations of meteorological stations in the Verwall region (St. Anton, station no. 14300) and in the Silvretta region (Galtür; homogenized HISTALP data) (Auer et al., 2007). Distance between the two stations amounts to approximately 20 km. Orthophoto of 2020 provided by © Land Tirol (Land Tirol – tiris, 2020). (b) Summer (JJA) temperature time series (1957–2001) from the two stations that exhibit similar trends in the period between 1957–2001 (data provided by Austrian Weather Service ZAMG).

All analytical information associated with cosmogenic nuclide measurements is listed in the tables within the paper and the Supplement.

The supplement related to this article is available online at: https://doi.org/10.5194/cp-17-2451-2021-supplement.

SMB and JMS designed the study. SMB, MF, and JMS carried out field work. SMB was responsible for cosmogenic nuclide sample preparation. AJH performed sample measurements and developed the strategy for low-level 10Be sample processing. All authors were involved in data interpretation. SMB wrote the manuscript, which was revised and edited by all authors.

The contact author has declared that neither they nor their co-authors have any competing interests.

Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.

Publisher’s note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Sandra M. Braumann is grateful to the LDEO cosmogenic nuclide laboratory staff Roseanne Schwartz and Jean Hanley for their help and advice during sample processing. Furthermore, Sandra M. Braumann thanks Günther Gross for helpful discussions on the Holocene moraine record in the Silvretta Massif, Dominik Blasenbauer for assistance during fieldwork, and Herbert Formayer for providing meteorological data. The authors express their gratitude to their hosts at the Jamtal hut, at Larainalpe, and at Pension Türtscher, who have facilitated the field campaigns. Finally, the authors thank two anonymous reviewers, whose comments greatly improved the manuscript, and Alberto Reyes, who was the editor of the manuscript. This work was performed in part under the auspices of the U.S. Department of Energy by Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory under Contract DE-AC52-07NA27344; this is LLNL-JRNL-821951.

This research has been supported by inatura Museum GmbH Dornbirn (funding period 2017–2019) and is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under grant no. NSF-1853881. Sandra M. Braumann is a recipient of a DOC Fellowship of the Austrian Academy of Sciences (OeAW) at the Institute of Applied Geology, University of Natural Resources and Life Sciences (BOKU) Vienna (grant no. 24709). For research visits at the LDEO, Sandra M. Braumann received a Marietta Blau scholarship sponsored by OeAD GmbH (grant no. ICM-2018-11638), a Marshall Plan scholarship provided by the Austrian Marshall Plan Foundation (grant no. 967116921 222019), and financial support from BOKU's “Transitions to Sustainability” (T2S) doctoral school.

This paper was edited by Alberto Reyes and reviewed by two anonymous referees.

Adolphi, F., Muscheler, R., Svensson, A., Aldahan, A., Possnert, G., Beer, J., Sjolte, J., Bjorck, S., Matthes, K., and Thieblemont, R.: Persistent link between solar activity and Greenland climate during the Last Glacial Maximum, Nat. Geosci., 7, 662–666, 2014.

Affolter, S., Hauselmann, A., Fleitmann, D., Edwards, R. L., Cheng, H., and Leuenberger, M.: Central Europe temperature constrained by speleothem fluid inclusion water isotopes over the past 14 000 years, Sci. Adv., 5, eaav3809, https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aav3809, 2019.

Alley, R. B.: The Younger Dryas cold interval as viewed from central Greenland, Quaternary Sci. Rev., 19, 213–226, 2000.

Alley, R. B. and Agustsdottir, A. M.: The 8k event: cause and consequences of a major Holocene abrupt climate change, Quaternary Sci. Rev., 24, 1123–1149, 2005.

André, M. F.: Rates of postglacial rock weathering on glacially scoured outcrops (Abisko-Riksgransen area, 68 degrees N), Geogr. Ann. A, 84A, 139–150, 2002.

Andrews, J. T., Jennings, A. E., Kerwin, M., Kirby, M., Manley, W., Miller, G. H., Bond, G., and Maclean, B.: A Heinrich-Like Event, H-0 (Dc-0) – Source(S) for Detrital Carbonate in the North-Atlantic during the Younger Dryas Chronozone, Paleoceanography, 10, 943–952, 1995.

Andrews, J. T., Gibb, O. T., Jennings, A. E., and Simon, Q.: Variations in the provenance of sediment from ice sheets surrounding Baffin Bay during MIS 2 and 3 and export to the Labrador Shelf Sea: site HU 2008029-0008 Davis Strait, J. Quaternary Sci., 29, 3–13, 2014.

Auer, I., Böhm, R., Jurkovic, A., Lipa, W., Orlik, A., Potzmann, R., Schöner, W., Ungersböck, M., Matulla, C., Briffa, K., Jones, P., Efthymiadis, D., Brunetti, M., Nanni, T., Maugeri, M., Mercalli, L., Mestre, O., Moisselin, J. M., Begert, M., Müller-Westermeier, G., Kveton, V., Bochnicek, O., Stastny, P., Lapin, M., Szalai, S., Szentimrey, T., Cegnar, T., Dolinar, M., Gajic-Capka, M., Zaninovic, K., Majstorovic, Z., and Nieplova, E.: HISTALP – historical instrumental climatological surface time series of the Greater Alpine Region, Int. J. Climatol., 27, 17–46, 2007.

Balco, G., Stone, J. O., Lifton, N. A., and Dunai, T. J.: A complete and easily accessible means of calculating surface exposure ages or erosion rates from Be-10 and Al-26 measurements, Quat. Geochronol., 3, 174–195, 2008.

Bamberg, A., Rosenthal, Y., Paul, A., Heslop, D., Mulitza, S., Ruhlemann, C., and Schulz, M.: Reduced North Atlantic Central Water formation in response to early Holocene ice-sheet melting, Geophys. Res. Lett., 37, L17705, https://doi.org/10.1029/2010GL043878, 2010.

Barclay, D. J., Wiles, G. C., and Calkin, P. E.: Holocene glacier fluctuations in Alaska, Quaternary Sci. Rev., 28, 2034–2048, 2009.

Baroni, C., Casale, S., Salvatore, M. C., Ivy-Ochs, S., Christl, M., Carturan, L., Seppi, R., and Carton, A.: Double response of glaciers in the Upper Peio Valley (Rhaetian Alps, Italy) to the Younger Dryas climatic deterioration, Boreas, 46, 783–798, 2017.

Beniston, M., Farinotti, D., Stoffel, M., Andreassen, L. M., Coppola, E., Eckert, N., Fantini, A., Giacona, F., Hauck, C., Huss, M., Huwald, H., Lehning, M., López-Moreno, J.-I., Magnusson, J., Marty, C., Morán-Tejéda, E., Morin, S., Naaim, M., Provenzale, A., Rabatel, A., Six, D., Stötter, J., Strasser, U., Terzago, S., and Vincent, C.: The European mountain cryosphere: a review of its current state, trends, and future challenges, The Cryosphere, 12, 759–794, https://doi.org/10.5194/tc-12-759-2018, 2018.

Bertle, H.: Zur Geologie des Fensters von Gargellen (Vorarlberg) und seines Kristallinen Rahmens – Österreich, Mitt. Ges. Geol. Berbaustud., 22, 1–60, 1973.

Bichler, M. G., Reindl, M., Reitner, J. M., Drescher-Schneider, R., Wirsig, C., Christl, M., Hajdas, I., and Ivy-Ochs, S.: Landslide deposits as stratigraphical markers for a sequence-based glacial stratigraphy: a case study of a Younger Dryas system in the Eastern Alps, Boreas, 45, 537–551, 2016.

Biette, M., Jomelli, V., Chenet, M., Braucher, R., Rinterknecht, V., Lane, T., and Team, A.: Mountain glacier fluctuations during the Lateglacial and Holocene on Clavering Island (northeastern Greenland) from(10)Be moraine dating, Boreas, 49, 873–885, 2020.