the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Terrestrial methane emissions from the Last Glacial Maximum to the preindustrial period

Thomas Kleinen

Uwe Mikolajewicz

Victor Brovkin

We investigate the changes in terrestrial natural methane emissions between the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM) and preindustrial (PI) periods by performing time-slice experiments with a methane-enabled version of MPI-ESM, the Max Planck Institute Earth System Model. We consider all natural sources of methane except for emissions from wild animals and geological sources, i.e. emissions from wetlands, fires, and termites. Changes are dominated by changes in tropical wetland emissions, with mid-to-high-latitude wetlands playing a secondary role, and all other natural sources being of minor importance. The emissions are determined by the interplay of vegetation productivity, a function of CO2 and temperature; source area size, affected by sea level and ice sheet extent; and the state of the West African monsoon, with increased emissions from northern Africa during strong monsoon phases.

We show that it is possible to explain the difference in atmospheric methane between LGM and PI purely by changes in emissions. As emissions more than double between LGM and PI, changes in the atmospheric lifetime of CH4, as proposed in other studies, are not required.

- Article

(6404 KB) - Full-text XML

- BibTeX

- EndNote

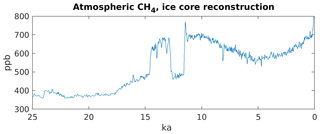

The atmospheric concentration of methane underwent major changes in the time between the last glacial maximum (LGM) and preindustrial (PI) periods. Between LGM and 10 ka (before 1950 CE) atmospheric CH4, as reconstructed from ice cores, nearly doubled from ∼ 380 ppb at LGM to 695 ppb at 10 ka (Köhler et al., 2017), with very rapid concentration changes of about 150 ppb occurring during the transitions from the Older Dryas to the Bølling–Allerød (BA), from the BA to the Younger Dryas (YD), and from the YD to the Preboreal (PB) or early Holocene (Fig. 1). Furthermore, while Holocene atmospheric CH4 was very similar for 10 ka and PI (694 ppb, mean concentration for 300 to 200 a BP), CH4 decreased linearly by 15 % from 10 to 5 ka and increased again linearly towards PI. If we assume that the atmospheric lifetime of CH4 did not change dramatically between the LGM and the present, these changes in atmospheric CH4 would require large changes in CH4 emissions.

The change in methane between LGM and PI has been investigated in a number of studies. Some have used box models to explain the methane changes observed in ice cores. Recently Bock et al. (2017), for example, pointed to tropical wetlands as the main driver of glacial–interglacial CH4 change from a study of methane isotopes from ice cores. In addition there are studies with comprehensive models. Kaplan (2002) investigated wetland CH4 emissions during the LGM and the present using the BIOME4 model. He finds wetland emissions of 140 Tg CH4 yr−1 (1 Tg=1012 g) for the present-day situation and 107 Tg CH4 yr−1 (−24 %) for the LGM, with wetland areas at the LGM slightly larger than at present. Valdes et al. (2005) performed time-slice experiments with the Hadley Centre Coupled Model (HadCM3), using the Sheffield Dynamic Global Vegetation Model (SDGVM) as a fire and wetland methane emission model, as well as an atmospheric chemistry model. They find PI wetland CH4 emissions of 148 Tg CH4 yr−1 and LGM emissions of 108 Tg CH4 yr−1 (−27 %), with tropical sources changing rather little and Northern Hemisphere (NH) high latitudes contributing most of the change in emissions. Emissions from biomass burning changed from 11 Tg CH4 yr−1 at PI to 7 Tg CH4 yr−1 at LGM (−36 %), contributing to the total emission change from 199 Tg CH4 yr−1 at PI to 152 Tg CH4 yr−1 at LGM (−24 %). Weber et al. (2010) investigated wetland emissions for PI and LGM time slices with climate forcings from the Palaeoclimate Modelling Intercomparison Project (PMIP2) ensemble, which is applied to an offline wetland CH4 model. They found an overall reduction by 29 %–42 %, with sources in the NH extratropics reduced by 51 %–60 %, while tropical sources were reduced by 22 %–36 %. Finally Hopcroft et al. (2017) investigated methane emission changes between LGM and PI using the Hadley Centre Global Environmental Model (HadGEM2-ES), considering wetlands, termites, and biomass burning as CH4 sources, along with ocean and geological emissions. They obtain an overall source reduction by 28 %–42 %, with LGM wetland emissions (97 and 80 Tg CH4 yr−1 if northern peatlands are considered explicitly) reduced by 30 % in comparison to PI (138 Tg CH4 yr−1), and termite emissions reduced by 40 %.

Figure 1Atmospheric CH4 as reconstructed from ice cores (Köhler et al., 2017, and references therein).

Studies of time slices between the LGM and PI are much sparser. Kaplan et al. (2006), using BIOME4-TG as a terrestrial methane emission model also determining emissions of biogenic volatile organic compounds (BVOCs) and an atmospheric chemistry model, investigated time slices every 1000 years from LGM to the present. They found that changes in atmospheric CH4 are largely due to a changed lifetime, mainly through BVOC emission changes. Interestingly, they find a larger wetland area for the LGM than for present day, with emissions roughly the same (∼110 Tg CH4 yr−1), and an emission maximum around 10 ka. Finally, Singarayer et al. (2011) investigated methane for 65 time slices between 130 ka and PI with HadCM3 and SDGVM as a methane emission model. They point to orbital changes driving the methane increase between 5 ka and PI, as insolation increases in the SH tropics.

What these studies have in common is that they require (in some cases substantial) changes in the atmospheric lifetime of methane to explain the changes in atmospheric CH4 reconstructed from ice cores. However, Levine et al. (2011) found very small changes in CH4 lifetime between LGM and PI using the TOMCAT (Toulouse Off-line Model of Chemistry And Transport) atmospheric chemistry model, which had also been found by Murray et al. (2014) and Hopcroft et al. (2017), who investigated CH4 lifetime using different atmospheric chemistry models. This small change in CH4 lifetime arises from the balance of several competing influences, such as changes in reactive compounds, changes in reaction rates due to temperature changes, and changes in atmospheric OH due to water vapour changes. As a result, substantial changes in emissions are required to explain the changes in atmospheric methane as seen in ice cores, and none of the previous studies have managed to obtain the required changes in methane emissions, while fulfilling the constraints of the present-day methane budget at the same time.

In the present-day top-down CH4 budget (Saunois et al., 2016), 59 % of the emissions are from anthropogenic sources can therefore be ignored for pre-anthropogenic times. However, 41 % (231 Tg CH4 yr−1) of the emissions are from natural sources and are therefore relevant for the entire time since the LGM. In the top-down budget, 167 Tg CH4 yr−1 (72 % of the natural emissions) are emitted from natural wetlands, and 64 Tg CH4 yr−1 come from “other” sources. These are not differentiated further in the top-down budget, but the bottom-up budget (Saunois et al., 2016) lists freshwater bodies (lakes), geological sources, wild animals, wildfires, permafrost soils, and vegetation as further onshore (land) sources and geological and other as offshore (oceanic) sources.

We aim to assess the changes in the natural sources of methane from the LGM to the present in order to determine the factors driving the changes in atmospheric CH4. We use a methane-enabled version of MPI-ESM, the Max Planck Institute Earth System Model, to investigate changes in natural methane emissions for six time slices from the LGM to the present. In this model we include submodels for methane fluxes from wetlands, termites, and wildfires, but the other natural methane fluxes listed above cannot easily be derived from the climate model state; therefore, they are neglected for now. As time slice experiments very likely are not helpful for looking into the BA–YD and YD–PB transitions, we neglect these at present, focusing instead on the longer timescale changes in methane.

2.1 MPI-ESM 1.2

We use the Max Planck Institute Earth System Model (MPI-ESM) in version 1.2 (Mauritsen et al., 2019), the version to be used in CMIP6. All experiments are performed in resolution T31GR30 (Mikolajewicz et al., 2018). In comparison to the CMIP5 version (Giorgetta et al., 2013), a number of errors were corrected in the atmosphere and ocean models, and the land surface scheme JSBACH (Reick et al., 2013; Brovkin et al., 2013; Schneck et al., 2013) has been updated with a multilayer hydrology scheme (Hagemann and Stacke, 2015), the SPITFIRE fire model (Thonicke et al., 2010; Lasslop et al., 2014), and the improved soil carbon model YASSO (Tuomi et al., 2009; Goll et al., 2015).

2.2 Wetland methane emission model

The present-day area that wetland methane emissions originate from is highly uncertain. The generation of methane in the soil is dependent on plant composition, carbon content, and carbon quality, essentially ecosystem properties, as well as the degree of anoxia in the soil, which depends on soil structure and water content, essentially hydrological properties. As there is no better estimate of the methane-generating area available, we determine the surface inundation and assume that this is a useful approximation of the areas where methane is generated.

2.2.1 Dynamic inundation model

We use an approach based on the TOPMODEL hydrological framework (Beven and Kirkby, 1979) to determine inundation extent dynamically. TOPMODEL is a conceptual rainfall–runoff model, based on the compound topographic index (CTI), , with αi being a dimensionless index for the area draining through point i and βi being the local slope at that point. TOPMODEL determines the local water table zi at point i in relation to the grid-cell-mean water table :

with χi being the local CTI index at point i, being the grid-cell-mean CTI index, and f being a parameter describing the exponential decline of transmissivity with depth. From Eq. (1) we determine the grid-cell fraction with a local water table depth zi≥0. Since inundated areas become unreasonably large in some locations, we limit the valid range of CTI values by introducing the constraint χi≥χmin following Stocker et al. (2014), with χmin being constant in space and time. We assume this to be the inundated and therefore methane-emitting area Ainun, unless soils are frozen. In these cases we determine the fraction of liquid water in the soil fliq from the soil temperature Tsoil

(limiting fliq to for numerical reasons), and we determine the inundated area as , reducing the inundated area under freezing conditions, as frozen soils emit less methane, similar to Gedney and Cox (2003).

To determine the grid-cell-mean water table position , we determine the layer saturation, , for each soil layer k by dividing the volumetric moisture content Θk by the field capacity Θfc. Starting from the bottom of the soil column, is located in the first soil layer l with layer saturation Ψl less than the saturation threshold Ψthres. The final water table position then is

with zb,l being the bottom of soil layer l, and Δzl being the height of soil layer l.

Values for f, χmin, and Ψthres were determined from sensitivity experiments. In the experiments described here, we use f=2.6, χmin=8.5, and Ψthres=0.95. Furthermore, comparison with remote-sensing data (Prigent et al., 2012) showed that inundated area in grid cells with a mean CTI index, , is negligible. Inundation is therefore only determined for grid cells with .

We use the CTI index product by Marthews et al. (2015) for the CTI index at a resolution of 15 arcsec in all present-day land areas, while we determine CTI index values for shelf areas that are below sea level at present, but above sea level under glacial conditions, from the ETOPO1 dataset (Amante and Eakins, 2009) using the TOPMODEL library for R (Buytaert, 2011). In order to reduce storage requirements, we approximate the distribution of CTI values within a model grid cell by fitting a gamma distribution, following Sivapalan et al. (1987).

2.2.2 Wetland methane production and transport

We use the methane transport model by Riley et al. (2011) to determine wetland methane emissions, with minor modifications to adapt the model to the vegetation and carbon cycle representation in JSBACH. The Riley et al. (2011) model determines CO2 and CH4 production in the soil; transport of CO2, CH4, and O2 through the three pathways (diffusion, ebullition, and and plant aerenchyma), and the oxidation of methane during transport.

Adaptations are described in the following. In the grid-cell fraction determined to be inundated by the inundation model, soil organic matter (SOM) is decomposed under anaerobic conditions in the YASSO soil carbon model (Goll et al., 2015), assuming a reduction of decomposition by a factor of 0.35 (Wania et al., 2010) in comparison to the aerobic case. As YASSO is a zero-dimensional representation of soil C processes, we distribute the decomposition product to the soil layers according to the root distribution from Jackson et al. (1996). Partitioning of the anaerobic decomposition product into CO2 and CH4 is temperature dependent, as in the original Riley model, with a baseline fraction of CH4 production fCH4=0.35 and a Q10 factor for fCH4 of Q10=1.8, with a reference temperature of 295 K.

For each grid cell, the methane model determines CH4 production and transport for two grid-cell fractions: the aerobic (non-inundated) and the anaerobic (inundated) fraction of the grid cell. If the inundated fraction changes, the amounts of CO2, CH4, and O2 are conserved, transferring gases from the shrinking fraction to the growing fraction (proportional to the area change). While vegetation in JSBACH is determined for vegetation tiles, allowing a fractional coverage of plant functional types, the relevant properties (root distribution, SOM decomposition) are aggregated to grid-cell level for the methane transport model for performance reasons. Previous sensitivity experiments showed that differences to a tile-resolving formulation are negligible.

2.3 Methane emissions from wildfires

To determine methane emissions from wildfires, we use the biomass burned, diagnosed from the SPITFIRE module (Thonicke et al., 2010; Lasslop et al., 2014), and information on vegetation composition from the dynamical vegetation model. We use the methane emission factors from Kaiser et al. (2012), mapped to the JSBACH plant functional types, to determine the fraction of burned biomass emitted as methane. Therefore, changes in fire-related methane emissions are completely determined by changes in fire carbon emissions. Fire occurrence in the SPITFIRE model is determined as a function of flammability (higher under dryer or warmer conditions) and ignition probability, with ignition probability a function of lightning frequency and population density. We are currently limited to a fixed lightning distribution reflecting modern conditions, and we are assuming a population density of zero for all time slices earlier than preindustrial. Therefore, the main factors affecting fire-related methane emissions are carbon content and moisture conditions.

For PI and PD, we use an estimate of population density to determine the ignition probability, with ignition probability increasing with population density. However, under very high population densities it is assumed that fire suppression increases, thus decreasing fire probability and thus fire methane emissions, for very high population densities.

2.4 Methane emissions from termites

Methane emissions from termites are determined following the approach developed by Kirschke et al. (2013) and elaborated by Saunois et al. (2016), adapted for the use in a dynamical vegetation model. They distinguish between termite emissions from tropical and nontropical areas, using different parameterisations for determining the termite biomass, Mtermite, and different emission factors for the two areas. For tropical areas, in our case defined as areas covered by the plant functional types (PFTs) tropical broadleaf evergreen tree, tropical broadleaf deciduous tree, and C4 grass, we determine Mtermite from the annual gross primary production GPP using (Kirschke et al., 2013). From Mtermite we determine methane emissions using an emission factor of 2.8 (Saunois et al., 2016). We define the nontropical areas with termite emissions, i.e. the areas where the tropical PFTs do not occur, as the areas suitable for temperate broadleaf evergreen trees using bioclimatic limits from Sitch et al. (2003): temperature of the coldest month, , and a growing-degree-day (GDD) sum on the basis of 5 ∘C (). In these areas we assume a constant termite biomass, , and an emission factor of 1.7 (Saunois et al., 2016). If croplands occur in any particular grid cell (not relevant for experiments presented here), emissions from the cropland tile are reduced to 40 % of the non-cropland grid-cell-mean emissions (also following Saunois et al., 2016).

2.5 Model experiments

We performed model experiments for five time slices at 20, 15, 10, 5 ka, and PI (in this case defined as the year 1850 CE). In addition we performed one transient historical experiment for the years 1850–2010 CE, starting from the PI time slice, in order to obtain a present-day (PD) climate state for evaluation purposes. All model experiments use prescribed orbital forcing from Berger (1978) and greenhouse gas forcings from Köhler et al. (2017). Orbital parameters and greenhouse gas concentrations are supplied to the model as 10-year mean values and are updated every 10 model years. Atmospheric aerosols were constant at 1850 conditions (Kinne et al., 2013), with the exception of the historical experiment, and we considered no anthropogenic land use.

The time slice experiments were initialised from a – so far unpublished – transient model experiment from 26 ka to PI with prescribed ice sheet extent from the GLAC-1D ice sheet reconstruction (Tarasov et al., 2012; Briggs et al., 2014; Ivanovic et al., 2016). This model experiment was initiated at 26 ka and run transiently from then to PI, i.e. the year 1850 CE. Ice sheet extent, as well as bathymetry and topography (Meccia and Mikolajewicz, 2018), and river routing (Riddick et al., 2018) were continuously updated throughout the deglaciation.

As the original transient experiments did not contain the methane code required for the experiments described here, the time slice experiments were initialised from the transient experiment with a three-step procedure to minimise climate drift from the original experiment. In the first step, all model components were initialised from the transient experiment, with the exception of the inundation and the methane model, which were initialised from scratch. The model was integrated for 20 years from this initial state. This was repeated for a second time, but using the inundation and methane states reached at the end of the initial experiment. In a third step, the model was run for 40 years, using the inundation and methane state reached at the end of step two, while using the conditions of the transient model experiments for all other model components. In this way we ensured that the state of the physical model, as well as the biogeochemistry, would always be as close as possible to the model state in the fully transient experiment.

We assess present-day (PD) conditions by performing a historical experiment for 1850–2010, initialised from the PI state of the transient deglaciation experiment. In the PD experiment we change greenhouse gas (GHG) and atmospheric aerosol transiently, using the Stevens et al. (2017) aerosol parameterisation, but we do not consider anthropogenic land use.

In order to further assess the changes in methane emissions between PI and 20 ka, we have performed additional sensitivity experiments, starting from the PI state. In experiment PI-C-LGM we impose 20 ka land carbon stocks in all grid points that are common between 20 ka and PI, and in experiment PI-CO2-LGM we impose 20 ka atmospheric CO2 on the land biogeochemistry but not on the atmospheric physics. These experiments allow us to assess the effects of soil carbon and CO2 changes on CH4 emissions while keeping climate unchanged. In experiments PI-noQ10 and 20k-noQ10, finally, we modified the CH4 production parameters (fCH4=0.28 and Q10=1.0) in such a way that partitioning between CO2 and CH4 is no longer temperature dependent, while giving similar total emissions in the PI state, thus mimicking the behaviour of models that do not take this factor into account.

Climate in the preindustrial state is very similar to the preindustrial control experiment described in Mauritsen et al. (2019) and Mikolajewicz et al. (2018). However, the orography used in the present experiments is different from that in the published preindustrial control experiments. The latter experiments employ a mean orography, while the orography in the transient deglaciation experiment that we used as starting conditions for our time slice experiments is an envelope orography. In the envelope orography, the grid-cell elevation is increased in comparison to the mean orography in order to better represent the influence of topography on atmospheric circulation in the coarse model resolution we are using. Technically, this is achieved by adding the standard deviation of elevation to the mean.

For all experiments, we analyse a 30-year mean climatology, with the exception of the PD experiment where we analyse a 10-year mean climatology obtained from years 2000 to 2009. All plots of absolute emissions are shown on the land–sea mask appropriate for the time interval under consideration, while difference plots show the outline of the PI land–sea mask.

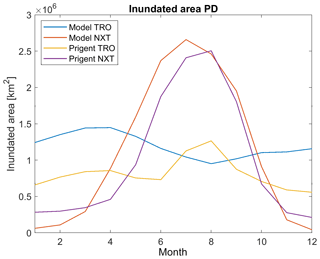

Figure 2Climatology of monthly-mean inundated area for model years 2000–2009 and Prigent et al. (2012) observations (1993–2007), which is separated for the tropics (TRO) and NH extratropics (NXT).

3.1 Evaluation of present-day methane emissions

3.1.1 Surface inundation

For the assessment of wetland methane emissions, the wetland area can to some extent be measured directly from satellites. Remote-sensing products of surface inundation are available, e.g. by Prigent et al. (2012) and Schroeder et al. (2015). To assess the quality of the modelled surface inundation, we rely on the Prigent et al. (2012) dataset. However, four points need to be considered when comparing these data to model results:

-

The remote-sensing process is unable to penetrate snow cover, so snow-covered areas are considered non-inundated.

-

The remote-sensing product shows all inundated areas, including areas flooded as a result of anthropogenic processes, such as the creation of reservoirs and rice paddies, which are not considered in the model.

-

Remote sensing may be unable to penetrate dense forest canopy, implying that inundation estimates may be biased in forested areas.

-

Not all methane-generating areas have water tables above the surface. Water tables in northern peatlands, for example, tend to be below the surface for part of the year, especially in the summer.

In order to make model output and remote-sensing data comparable, we therefore mask all snow-covered areas in the model output, and we use data on rice-growing areas by Monfreda et al. (2008) to mask all rice-growing areas from both the remote-sensing data and the model output. After these modifications, modelled inundated areas for the present-day period (mean over 2000–2009) are slightly larger than those observed by Prigent et al. (2012) (mean over 1993–2007) (Fig. 2). For the tropics (TRO, here for simplicity defined as latitudes between 30∘ N and 30∘ S) the annual mean inundated area is 1.2×106 km2 in the model results, while Prigent et al. (2012) show 0.8×106 km2. The seasonality is phase shifted, with the model showing the peak inundation in April, while Prigent et al. (2012) show the inundation peak in August (Fig. 2). For the glacier-free NH extratropics (NXT, here defined as north of 30∘ N), the seasonality of inundation is similar in observations and model, but the summer peak in inundation is larger in the model (2.5×106 km2 for the JJA mean) than in the observations (2.3×106 km2).

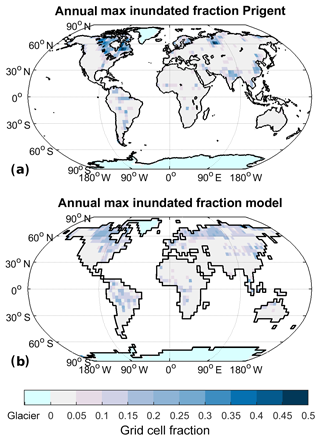

Figure 3Annual maximum of mean monthly inundated fraction for Prigent et al. (2012) (a) and model (b).

Comparing the spatial pattern of the annual maximum inundation (Fig. 3), the overall pattern is rather similar, although two major differences are apparent: (1) the annual maximum inundation is more localised in the observations, while it is less clearly defined and reaching lower maximum values in the model, and (2) after removal of the rice-growing areas the model does not show a significant inundation maximum in India. These differences are likely due to the low resolution of the model we are employing. At higher resolutions, inundation becomes more localised and thus (1) appears clearly related to resolution and (2) is due to an underestimate of the Indian monsoon precipitation, also likely due to the low model resolution. We thus judge the methane-generating areas produced by the model as reasonable, keeping in mind the likely low bias of the remote-sensing inundation product.

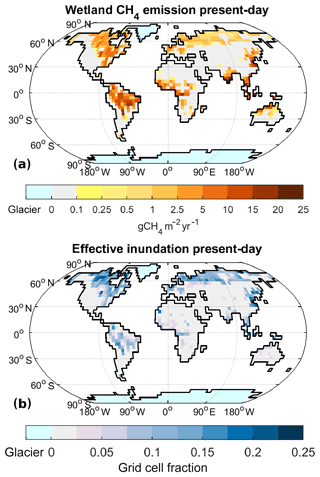

As described above, we use the inundated area to determine the methane-emitting area. To evaluate the inundated areas leading to the wetland emissions, it has to be kept in mind that NXT emissions mainly are from the summer season, implying that the JJA (June, July, August) mean inundation is relevant for these, while the seasonality of TRO emissions is much less pronounced, implying that the annual mean inundation is relevant. In the following we therefore assess the effective inundated area, which is defined as the annual mean inundated area in tropical latitudes (TRO, between 30∘ N and 30∘ S), and the JJA (June, July, August) mean inundated area in the glacier-free NH extratropics (NXT, north of 30∘ N). For the present-day climate state, the effective inundated area is 1.5×106 km2 in TRO and 2.6×106 km2 in NXT (differences to the numbers shown above due to the removal of rice-growing areas in the comparison to observations).

3.1.2 Natural methane emissions

So far it has not been possible to directly measure the quantity – surface methane fluxes – that we aim to assess in this publication on appropriate scales. Methane flux measurements exist for single sites on the scale of meters, mainly using measurement chambers, and for slightly larger scales, using eddy-covariance towers, but so far the scales relevant for global-scale modelling, from the model grid cell to global scales, have not been covered by direct methane flux measurements (Melton et al., 2013; Saunois et al., 2016; Poulter et al., 2017). For assessment of our model experiments, we therefore need to rely on global assessments (Saunois et al., 2016), and we can gain some additional insight from atmospheric inversions (Bousquet et al., 2011).

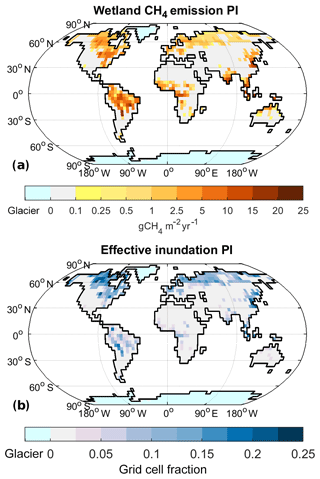

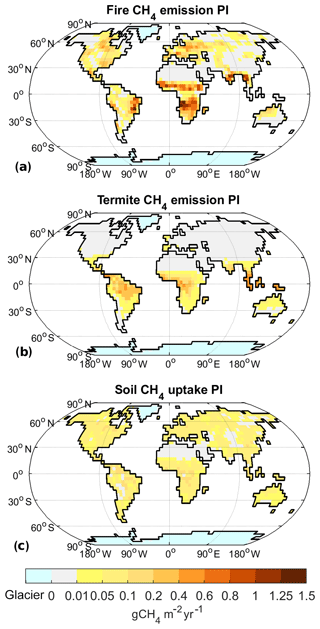

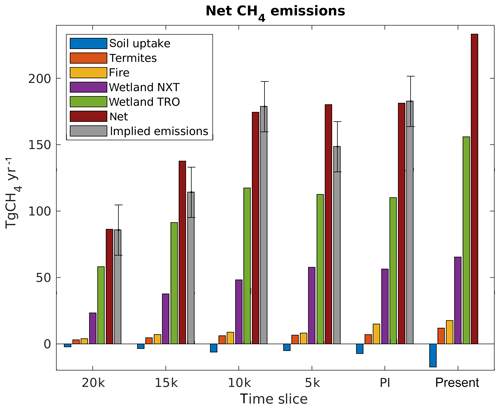

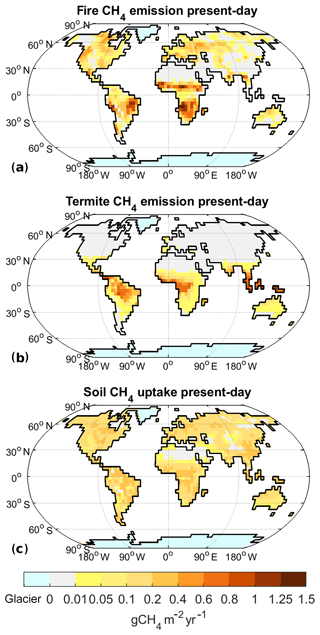

Under present-day (PD) climatic conditions (i.e. years 2000–2009 in the transient historical experiment), the model simulates wetland methane emissions of 222 Tg CH4 yr−1 (209–239 Tg CH4 yr−1), fire emissions of 17.6 Tg CH4 yr−1 (15.6–18.8 Tg CH4 yr−1), termite emissions of 11.7 Tg CH4 yr−1 (10.8–12.2 Tg CH4 yr−1), and a soil uptake of 17.5 Tg CH4 yr−1 (17.4–17.7 Tg CH4 yr−1). The values shown are mean values over the years 2000–2009 of the historical experiment, with the value in brackets giving the minimum and maximum annual emissions occurring in the model results. These values fall well within the ranges reported by Saunois et al. (2016), who report 153–227 Tg CH4 yr−1 for natural wetlands; 27–35 Tg CH4 yr−1 for biomass and biofuel burning, with biofuel burning making up 30 %–50 %; 3–15 Tg CH4 yr−1 for termites; and 9–47 Tg CH4 yr−1 for the soil uptake. Spatial patterns of modern emissions (Figs. B1 and B2) are generally similar to those shown by Saunois et al. (2016).

Furthermore, wetland methane emission estimates from atmospheric inversions (Bousquet et al., 2011) show that the majority (62 %–77 %) of the PD emissions come from the TRO region, while a much smaller part (20 %–33 %) are emitted from NXT. Of the modelled total wetland CH4 emissions for PD conditions, 156 Tg CH4 yr−1 (70 %) is from TRO and 65 Tg CH4 yr−1 (29 %) is from NXT, while emissions from the SH extratropics (here defined as south of 30∘ S) are negligible. The latitudinal distribution of modelled PD wetland methane emissions, therefore, is well within the range obtained from atmospheric inversions.

Overall, the PD state is rather similar to the PI state assessed in the following section, with very small differences in the distribution of emissions (Figs. B1 and B2), but generally higher methane emissions. At 287.4 K, the global mean temperature in the PD climate state is 0.5 K warmer than preindustrial (Table 1). Precipitation is similar, leading to negligible differences in the effective inundation. With 1140 Pg C, 8 % larger than PI, the global soil C stock is also rather similar. However, vegetation productivity is enhanced in comparison to PI, due to warmer temperatures and higher CO2 concentrations. The net methane emissions in the PD climate are 29 % larger than PI (Table 2). Wetland methane emissions are 33 % larger, with a larger increase (+42 %) in TRO than in NXT (+16 %). Fire emissions are 18 % larger than PI, termite emissions increase by 66 %, and the soil uptake increases by 140 %. The latter increase is largely due to the higher atmospheric concentration of CH4, which drives additional methane into the soils in comparison to the lower-CH4 PI state. The larger fire emissions are mainly due to higher population densities in the 2000s than in 1850, although the very high population densities in eastern North America, Europe, and southern Asia are assumed to drive an increase in fire suppression in the SPITFIRE model (Lasslop et al., 2014). Thus fire emissions are decreased here, despite the general increase in most other places. Termite emissions are higher in the modern climate due to an increase in GPP under higher CO2, while wetland emissions largely increase due to the higher temperatures of the modern climate, with CO2-fertilisation playing an additional role.

3.2 Preindustrial methane emissions

The climate in our PI experiment is very similar to the one described by Mikolajewicz et al. (2018). The global mean near-surface air temperature is 286.9 K (Table 1). The annual mean temperature in the TRO area, TTRO, is 294.5 K, while TNXT, the annual mean temperature in the NXT area, is 275.2 K. The NH ice sheet area is limited to Greenland, with the ice sheet having an area of 1.8×106 km2 in our model setup. Under these climatic boundary conditions, we obtain total net methane emissions of 181 Tg CH4 yr−1 (Table 2), with wetlands contributing 167 Tg CH4 yr−1 (Fig. 4a), fire and termites 15 and 7.0 Tg CH4 yr−1, respectively (Fig. 5a and b), and the soil uptake is 7.3 Tg CH4 yr−1 (Fig. 5c).

Wetland emissions, the dominant natural component of the terrestrial methane fluxes, mainly originate in TRO (110 Tg CH4 yr−1), while emissions from NXT are 56 Tg CH4 yr−1 (Table 2). The main factors determining wetland methane fluxes, apart from temperature, are the emitting area and the soil carbon stock that the soil respiration (and thus methane production) is derived from. In the PI state the global effective inundated area is 4.0×106 km2 (Fig. 4b), of which 2.7×106 km2 is located in NXT, while 1.3×106 km2 is in TRO (Table 1). For soil carbon, on the other hand, the global stock is 1054 Pg C (1 Pg=1015 g), with most of the soil carbon (588 Pg C) located in NXT, while it is 439 Pg C in TRO.

Methane emissions from fires (Fig. 5a) closely follow the fire distribution, with most fire methane emissions coming from subtropical Africa and South America, although some emissions also originate in North America, Southern Europe, and southern Asia. Termite emissions, on the other hand, mainly originate from tropical regions, especially southern Asia, with minor contributions from subtropical regions on all continents (Fig. 5b). Methane uptake by upland soils (Fig. 5c), finally, is distributed widely with no large regional variations.

3.3 Wetland methane emissions

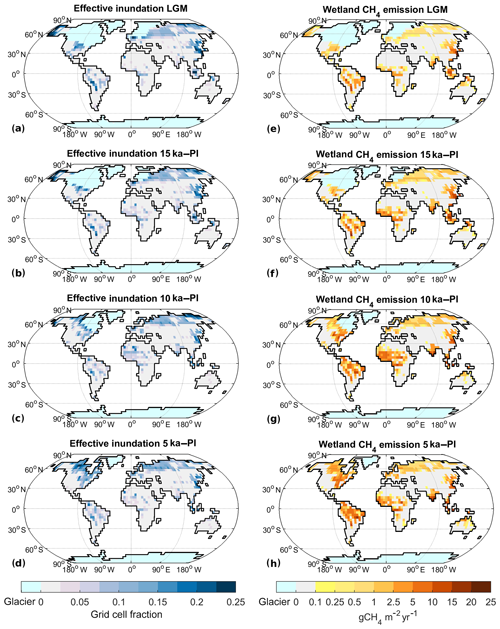

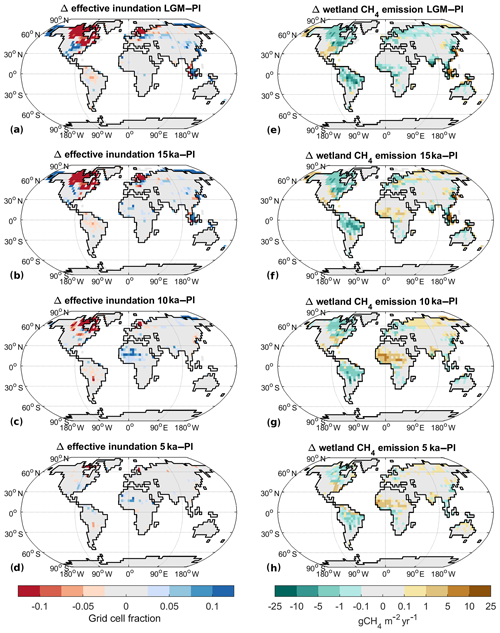

Figure 6Change in effective inundation and wetland methane emissions for past climate states: (a–d) inundation difference to PI, (e–h) CH4 emission difference to PI. (a, e) LGM, (b, f) 15 ka, (c, g) 10 ka, and (d, h) 5 ka.

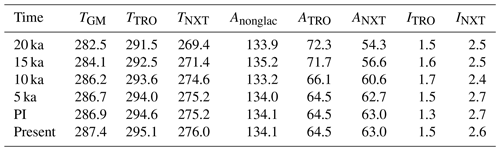

Table 1Climate and areas given in experiments. Global mean annual temperature TGM, TRO temperature TTRO, and NXT temperature TNXT (all in kelvin). Global nonglaciated land area Anonglac, TRO area ATRO, NXT area ANXT, TRO effective inundated area ITRO, and NXT effective inundated area INXT (all in 106 km2).

Under LGM boundary conditions the global mean temperature is 4.4 K colder than under PI conditions (Table 1). Extensive glaciers cover the NH extratropics and sea level is lower, leading to a 15 % increase in total land area, although total glacier-free area is nearly identical (Table 1). Thus, the TRO area, ATRO, is 12 % larger than PI, while the NXT area, ANXT (by definition glacier free), is 14 % smaller. The temperature decrease is less pronounced in TRO (−3.1 K) than in NXT (−5.8 K). Precipitation decreases by 10 % in the global mean, with an 11 % decrease in TRO and a 19 % decrease in NXT. TRO effective inundated area ITRO thus increases by 19 % (Table 1, Figs. 6a, B3a), while NXT effective inundated area INXT decreases by 6 %. The global soil C stock is 617 Pg C, substantially smaller (−41 %) than at PI, with the decrease smaller in TRO (−33 %) than in NXT (−49 %). As a result of these climate changes, wetland methane emissions decrease by 51 % (Table 2, Figs. 6e, B3e), with a TRO emission decrease of 47 %, while NXT emissions decrease by 59 %, with the majority of the latter emissions coming from areas in East Asia adjacent to the Yellow Sea and North America south of the Laurentide ice sheet. The wetland CH4 emissions therefore decrease nearly everywhere (Fig. 6e), with one major exception: the continental shelf areas that are exposed due to the lower sea level become significant sources of methane, especially in Indonesia but also in Africa and Asia. At 29 Tg CH4 yr−1, they contribute about 35 % of the total wetland CH4 emissions at the LGM.

Analysing the factors leading to the reduction in 20 ka wetland CH4 emissions further (see Appendix A for details), we can explain a reduction of emissions by 42 % in comparison to PI by the changes in land carbon and atmospheric CO2. Changes in temperature lead to a further reduction by about 20 %, while changes in available land points actually lead to an increase in emissions, as the available land points in the northern high latitudes (with low emissions) are reduced, while the available land points in the tropics (with high emissions) are increased.

For 15 ka, the global mean temperature change is −2.8 K relative to PI. NH ice sheet extent is 24 % lower than at LGM but still extensive. The total land area is 12 % larger than PI due to the lower sea level, but Anonglac is only larger by 1 %. ANXT is thus reduced by 10 % (Table 1), while ATRO is increased by 11 %. The change in TTRO is −2.0 K (Table 1), while it is −3.8 K for TNXT. Precipitation decreases by 6 % in the global mean, with a 4 % decrease in TRO and a 10 % decrease in NXT. Precipitation in NH Africa is slightly increased due to a stronger West African monsoon. ITRO thus is larger by 29 %, while INXT is 8 % smaller than PI (Table 1, Figs. 6b, B3b). Global soil C is at 815 Pg C (−23 %), with TRO C stocks at 398 Pg C (−9 %), while NXT stocks are at 392 Pg C (−33 %). Total wetland methane emissions decrease by −22 % as a result, with TRO emissions decreasing by 17 % and NXT emissions of by 33 % (Table 2, Figs. 6f, B3f). In contrast to the LGM situation, there is an increase in CH4 emissions from NH (sub)tropical Africa (Fig. 6f) to 19 Tg CH4 yr−1 (+58 %), due to wetter conditions in the Sahel area. The exposed shelf areas emit about 38 Tg CH4 yr−1 overall (29 % of the total emissions).

For 10 ka, our model indicates a global mean temperature change of −0.7 K (Table 1). Glacial area is much reduced in comparison to the LGM, but remains of the Laurentide ice sheet still cover parts of northeastern Canada, leading to a lower sea level than at PI. Thus, the total land area is 3 % larger than at PI (Anonglac−1 %), with ATRO 3 % larger due to lower sea level and ANXT 4 % smaller due to the remaining ice sheet coverage. The temperature decrease is larger in TRO (−1.0 K) than in NXT (−0.6 K). Precipitation is near PI levels in the global mean (−1 %), with a 6 % increase in TRO and a 1 % decrease in NXT. Precipitation in NH Africa is strongly increased due to a strong West African monsoon. ITRO is increased by 35 %, mainly due to the wetter conditions in north Africa, while INXT is decreased by 12 % in NXT (Table 1, Figs. 6c, B3c). Global soil C is at 983 Pg C, quite near the PI total stock (−7 %), with a TRO soil C stock of 449 Pg C (+2 %) and a NXT stock of 510 Pg C (−13 %). As a result, wetland CH4 emissions are very similar to PI (Table 2), with +7 % in TRO wetland emissions and −14 % in NXT emissions (Table 2, Figs. 6g, B3g). The increase in TRO emissions mainly occurs in the Sahel area, where the West African monsoon is strongly increased, leading to more precipitation, increased inundated area, and more biomass and soil C. Emissions from NH Africa are 37 Tg CH4 yr−1 (+208 %), which is an increase larger than the total increase in TRO emissions. Emissions from the (small) exposed shelf areas are at 8 Tg CH4 yr−1 (5 % of the total wetland CH4 emissions). NXT emissions are smaller than PI in North America and Europe, but they are larger than PI in northern Asia, due to the summer warming from the changed insolation at 10 ka.

At 5 ka, global mean temperature change is at −0.2 K (Table 1). Ice sheet areas are as in the PI state; thus, TRO and NXT areas are unchanged. TTRO is slightly lower (−0.6 K), but TNXT is very similar to PI. Precipitation changes are very small in the global mean, with a 4 % increase in TRO and a 2 % increase in NXT, with the West African monsoon slightly stronger than PI. ITRO increases by 15 %, while INXT decreases by 1 % (Table 1, Figs. 6d, B3d). Global soil C stocks are 1043 Pg C, slightly smaller than preindustrial (−1 %), with an increase by 4 % in TRO, especially in the southern Sahel region, while NXT is 4 % lower than PI. Total wetland methane emissions increase by 2 %, with TRO and NXT wetland emissions both increasing by 2 % (Table 2). Emissions from NH Africa are 21 Tg CH4 yr−1 (+75 % compared to PI, 19 % of TRO emissions), while emissions from the SH are generally decreased. NXT emissions are decreased in northern North America, while emissions from northern Asia and southern North America are increased.

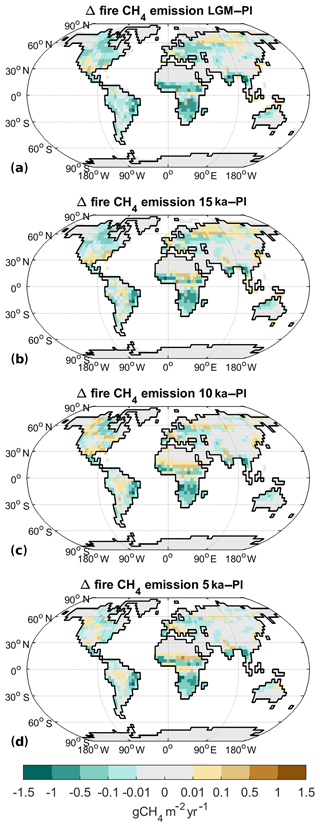

3.4 Methane emissions from wildfires

For all time slices before PI, we assume that no humans were present, leading to a generally decreased probability of fire ignition in comparison to PI and PD. For the LGM (Fig. 7a), fire CH4 emissions (Table 2) are 73 % smaller. As biomass is reduced strongly under the cold and low-CO2 conditions of the LGM, fire-related C emissions are also reduced. At 15 ka (Fig. 7b) fire emissions are 53 % lower than PI, while they are 40 % lower at 10 ka (Fig. 7c). Generally, the spatial pattern of emission changes at 15 and 10 ka mainly reflects precipitation changes: enhanced emissions occur in areas where precipitation is reduced, enhancing vegetation flammability. In the Sahel area, this relationship is different, though. Here, the enhanced rainfall leads to an increase in vegetation cover, especially grass cover. As a result, more biomass is available for combustion, leading to enhanced emissions. At 5 ka, finally, fire emissions are reduced by 45 %. As climate is already relatively similar to the PI situation, the main reason for the fire emission reduction here is the smaller ignition probability due to the absence of humans.

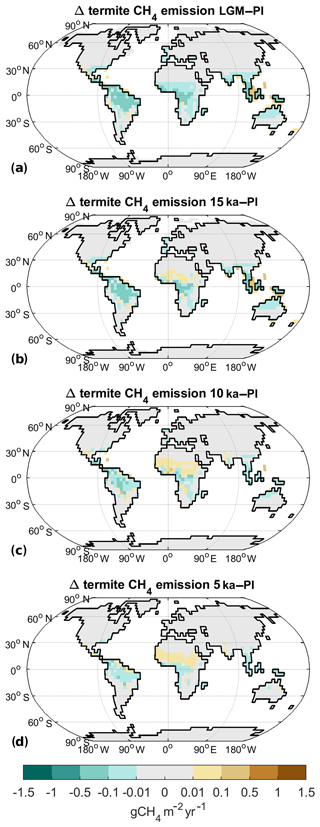

3.5 Methane emissions from termites

Termite emissions are mainly determined by gross primary productivity (GPP) in tropical and subtropical areas. The lower atmospheric CO2 and temperature under LGM conditions decrease GPP everywhere. Therefore, termite CH4 emissions are reduced by 58 % relative to the PI level (Table 2). For 15 ka, there also is a general reduction in termite emissions, with 4.6 Tg CH4 yr−1 in total (−34 %). However, the enhanced rainfall in the Sahel area leads to an increase in termite methane in this area. The latter is similar at 10 ka, where total emissions are 13 % smaller in comparison to PI. The enhanced productivity in the Sahel, therefore, more than compensates the decrease in termite methane from the Amazon and African rain forests. At 5 ka, finally, termite emissions are slightly smaller than PI (−7 %), with minor decreases in the rain forest areas and a slight increase in the Sahel.

3.6 Methane uptake by soils

The soil continually exchanges methane and oxygen with the atmosphere through diffusion. In areas where soil conditions are aerobic, methane concentrations in the soil are smaller than atmospheric concentrations, thus driving a flux of methane into the soil. In the soil the methane is oxidised, with oxidation rates dependent on the concentrations of CH4 and O2, as well as temperature. The gas exchange between soil and atmosphere is also modified by the presence of plants, as some plant tissues can transport gases between plant roots and leaves.

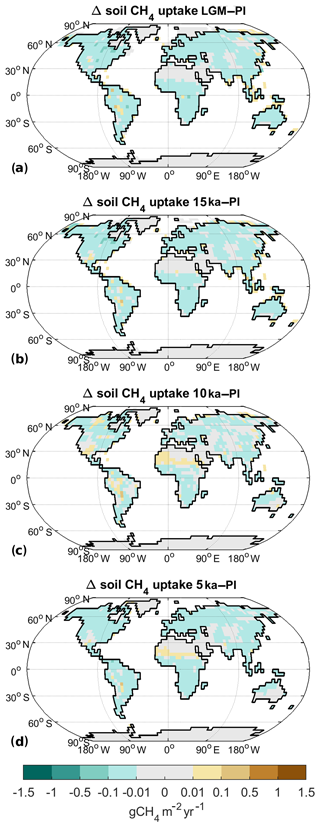

In our experiments, we find that the soil uptake of methane is to a large extent determined by the gradient of methane between soil and atmosphere. Thus higher atmospheric concentrations of methane directly lead to a larger soil uptake of methane. Under LGM conditions, the atmospheric CH4 concentration is 370 ppb, which is slightly less than half the PI concentration. Consequently soil methane uptake decreases by 68 % compared to PI (Table 2), with decreased temperatures being an additional factor (Fig. 9a). At 15 ka (atmospheric CH4 of 464 ppb), the soil uptake is 52 % smaller, while it is changed by −14 % at 10 ka (688 ppb) and −28 % at 5 ka (579 ppb). Spatially, the change in methane uptake is rather uniform, showing a similar reduction in uptake in most locations (Fig. 9). The exception to this is, once again, the Sahel area, which shows an increase in methane uptake most pronounced for 10 ka (Fig. 9c) but also for 5 ka (Fig. 9d). For these time slices, the increase in vegetation cover in the Sahel region leads to a localised increase in methane uptake.

3.7 Time slice comparison

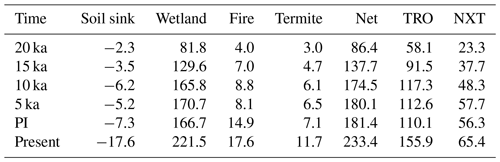

The net natural methane flux, i.e. the sum of all flux components, increases from 86 Tg CH4 yr−1 at 20 ka (−52 % compared to PI) to 181 Tg CH4 yr−1 in the PI state (and 233 Tg CH4 yr−1 (+29 %) at present).

Table 2Methane emissions for all time slices (in Tg CH4 yr−1). Shown are soil uptake, total wetland emissions, fire and termite emissions, net emissions, and wetland emissions from TRO and NXT.

The wetland emissions from TRO are the most important component of the net methane flux during all time slices. Their contribution is smallest at PI (61 % of total net emissions) and largest at 20 ka (67 %). The contribution from NXT ranges from 27 % at 20 ka to 32 % at 5 ka. Fire emissions make up 4 %–5 % in the purely natural states between 20 and 5 ka and about 8 % for the anthropogenically influenced states at PI and PD. Termite emissions make up between 3.4 % and 5.0 % of net emissions, and soil uptake reduces the emissions by between 2.5 % at 15 ka and 7.0 % in the PD state (Table 2). Our modelled CH4 emissions are also supported by the interpolar gradient in methane, as reconstructed by Baumgartner et al. (2012) for the LGM and Mitchell et al. (2013) for PI. Mitchell et al. infer tropical emissions of about 125 Tg CH4 yr−1 and NXT emissions of about 66 Tg CH4 yr−1 for the PI state (estimated from their Fig. 1), while Baumgartner et al. infer tropical emissions of about 60 Tg CH4 yr−1 and NXT emissions of about 25 Tg CH4 yr−1 for the LGM (estimated from their Fig. 5b).

In the modelled emissions, we are missing two components of the natural methane cycle: wild animals and geological sources. For geological emissions, estimates vary widely, with bottom-up estimates in Saunois et al. (2016) of 35–76 Tg CH4 yr−1 for on- and offshore sources, while Petrenko et al. (2017), estimating methane 14C for the YD from ice cores, constrain methane stemming from old carbon reservoirs to the range 0–18.1 Tg CH4 yr−1 at the YD. These fluxes likely are constant in time, although there might be changes during periods of sea level rise and fall, as hypothesised for CO2 by Huybers and Langmuir (2009). Methane emissions from wild animals, especially ruminants, are very difficult to estimate; current estimates for the present span a range 2–15 Tg CH4 yr−1 (Saunois et al., 2016), and estimates for other time slices are even less confident but might be of the order of 15–20 Tg CH4 yr−1 for times before significant human influence (Chappellaz et al., 1993). In principle, these emissions should somehow be related to the net primary productivity, as this would determine the carrying capacity of the ecosystem, implying smaller fluxes in the glacial than in the Holocene. Adopting the ice-core-based estimate by Petrenko et al. (2017) for the geological fluxes, we can thus hypothesise these to be , while wild animals might add . The total unaccounted fluxes might therefore be of the order of .

To compare the net fluxes to the reconstructed atmospheric CH4 concentrations from ice cores, we determined the implied methane emissions (Fig. 10). We converted the methane concentrations into a methane burden, using a conversion factor of 2.767 Tg CH4 ppb−1 (Dlugokencky et al., 1998). With a tropospheric lifetime of 9.3 years (range given 7.1–10.6 years) – an approximation for the present-day situation (Saunois et al., 2016) – we then determined the methane flux required to obtain the CH4 concentration reconstructed for all time slices except the present-day period, which is dominated by anthropogenic emissions. From this flux, we subtracted the unaccounted sources, as described above, to determine the implied emissions. Uncertainties from the unaccounted fluxes are represented as error bars; however, the uncertainty in tropospheric lifetime is not considered here but would roughly add another 15 %.

Comparing the modelled net emissions to the implied emissions (Fig. 10), the modelled fluxes are within the range of uncertainty for all time slices except for 15 and 5 ka, with modelled net emissions larger than the implied fluxes for these time slices. The net emissions increase by more than 100 % going from 20 to 10 ka (and PI); we can thus explain the methane increase from LGM to Holocene with CH4 emissions only and not requiring changes in methane lifetime. However, we so far cannot explain the Holocene changes in atmospheric CH4: decreasing between 10 and 5 ka and increasing subsequently. For 5 ka, Singarayer et al. (2011) explain the decreased emissions in comparison to PI by reduced SH precipitation, leading to lower wetland CH4 emissions. We obtain a similar result in our model, with SH wetland emissions reduced by 10 Tg CH4 yr−1 in comparison to PI. However, our NH emissions are substantially larger than at PI, due to substantial increases in Sahel precipitation and wetland emissions. We assume that this is due to an overestimate of the West African monsoon and its impact on African methane emissions, as a general reduction in the West African monsoon would lead to decreases in TRO emissions for 15, 10, and 5 ka, bringing model results more in line with the implied emissions determined from ice core CH4. However, this is speculative at this point and would require further experiments.

In this assessment we considered all natural emissions of methane, with the exception of emissions from wild animals and geological sources. In our experiments we found that it is possible to explain the difference between LGM (20 ka) and PI methane concentrations purely by changes in the emissions of methane, without requiring changes in the atmospheric lifetime of CH4. The time slice experiments we performed suggest that there are three main drivers to changes in methane emissions over the time from the LGM to the present:

-

The first main driver is global mean temperature and CO2. Higher atmospheric CO2 concentrations increase net primary production (NPP) and thus also soil carbon available for anaerobic decomposition to CH4. Similarly, higher global mean temperature also increases NPP and soil C decomposition, and it furthermore increases the ratio of CH4 to CO2 production in anaerobic decomposition. Thus, higher atmospheric CO2 and higher global mean temperature lead to larger wetland emissions of CH4. This affects emissions from wildfires and termites in a similar way, as fire C release is dependent on biomass and termite biomass is dependent on GPP and thus CO2 and temperature.

-

The second main driver is ice sheet area and sea level. Larger ice sheets remove CH4 sources in the Northern Hemisphere extratropics as these are covered by the ice sheets, which is especially important for wetland methane emissions from North America. At the same time large ice sheets lower sea level, enlarging tropical wetland area as the continental shelf is exposed and becomes a significant source of methane. This is mainly relevant in the tropics, as high-latitude shelf areas exposed under glacial conditions, e.g. the Laptev Sea shelf, experience extremely cold conditions in glacial climate, leading to negligible methane emissions. Exposed shelf areas in Indonesia, Africa, and South America, on the other hand, emit significant amounts of methane. Thus lower sea level leads to larger emitting areas and thus higher emissions of methane.

-

The third main driver is the West African monsoon. During the time slices when the West African monsoon is stronger than at present, i.e. at 15, 10, and 5 ka, precipitation in the Sahel region is significantly enhanced in comparison to the PI state, leading to an increase in vegetation cover, productivity, and biomass burning. As a result, methane emissions at these times are stronger than at present, leading to a significant increase in (sub)tropical CH4 emissions, with all natural methane sources increased.

For methane emissions from wildfires, a further factor influencing the emissions is the human population density, as this strongly affects the fire probability in the SPITFIRE model employed in JSBACH (Fig. 10). The soil uptake of methane, on the other hand, is strongly dependent on the atmospheric concentration of methane (Fig. 10).

The changes in methane from LGM to the present are dominated by changes in tropical wetland emissions, with mid- and high-latitude wetland emissions being a significant but secondary factor, gaining in importance as the high latitudes become ice free. Wetland emissions make up 93 %–96 % of the net CH4 flux, and all other methane sources are thus of minor importance.

The large changes in wetland methane emissions between PI and 20 ka are due to a combination of several factors. While climate change is the ultimate cause of all of these influences, it is possible to identify several individual factors that likely contributed, and may have led to, the larger changes in methane emissions than in some previous studies. (1) Due to sea level fall and glacier expansion, the ice-free land domain changes appreciably; (2) reduced soil carbon at 20 ka leads to less organic matter being available to be decomposed; and (3) reduced atmospheric CO2 leads to lower vegetation productivity and litterfall, and thus reducing both the plant transport of methane and the availability of soil organic matter for decomposition. In addition, (4) the temperature dependence of the ratio of CH4 and CO2 production in anaerobic soil organic matter decomposition is a relatively recent finding not considered in all methane transport models yet (Xu et al., 2016), and it may also have played a role. In order to further assess these factors, we conducted a set of sensitivity experiments, as detailed in Sect. 2.5.

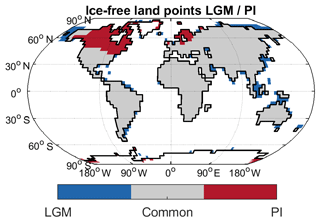

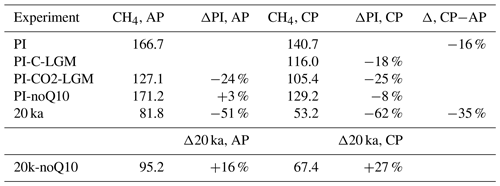

The ice-free land domain changes appreciably between PI and 20 ka (Fig. A1), with expanded ice sheets reducing the available area in the NH high latitudes, and lower sea level exposing additional land both in the high latitudes and in the tropics. Restricting analysis to the glacier-free land points common to both the PI and 20 ka time slices leads to a reduction in emissions by 16 % for the PI state and by 35 % for the LGM state (Table A1). The change in ice sheets and sea level thus leads to an increase in 20 ka wetland emissions compared to a state where the land–sea mask does not change, as some of the additional 20 ka grid points are located in the tropics, where large amounts of methane are emitted.

Table A1Sensitivity experiment results: wetland CH4 emissions (Tg CH4 yr−1) on all grid points (AP), emission change ( %) with regard to PI state on all points, wetland emissions (Tg CH4 yr−1) on the common grid points (CP), emission change ( %) with regard to PI state on the common points, and emission change between common points and all points (%). The reference state for emission change in experiment 20k-noQ10 is the 20 ka state.

Imposing 20 ka land carbon stocks in experiment PI-C-LGM leads to a further reduction by 18 % (evaluated for the common grid points), while imposing 20 ka atmospheric CO2 for the land biogeochemistry in experiment PI-CO2-LGM leads to a CH4 emission reduction by 24 % and 25 %, evaluated for all grid points and the common grid points, respectively. The combined effect of 20 ka land carbon and CO2 is thus a 42 % reduction in emissions (common grid points). The remaining reduction by 20 % of the PI emissions on the common grid points thus needs to be explained by other factors, with temperature change being most important.

Another factor that may be different in our model in comparison to the models previously employed is the temperature dependence of the CO2-to-CH4 partitioning during anaerobic decomposition. Disabling this temperature dependence in experiment 20k-noQ10 leads to a 16 % increase in CH4 emissions, with parameters chosen in such a way that the change is negligible (+3 %) for the PI state. The enabled temperature dependence of the CO2 to CH4 partitioning in the standard setup is thus a factor that reduces 20 ka emissions further.

For the convenience of readers, who are more interested in absolute emissions than in the differences to the PI state, we also provide an overview over the absolute emissions for the present-day situation (Figs. B1 and B2), as well as the absolute wetland emissions for the past time slices (Fig. B3).

Figure B1Wetland CH4 emissions for present-day climate (2000–2009): annual emissions of CH4 from wetlands (a) and effective inundation (b). Please note the different colour scale for (b) in comparison to Fig. 3.

The primary data, i.e. the model code for MPI-ESM, are freely available to the scientific community and can be accessed with a license on the MPI-M model distribution website http://www.mpimet.mpg.de/en/science/models (last access: 20 March 2020). In addition, secondary data and scripts that may be useful in reproducing the authors' work are archived by the Max Planck Institute for Meteorology. They can be obtained by contacting the first author or publications@mpimet.mpg.de.

TK developed the methane module, performed model experiments, and wrote the paper. UM performed the transient model experiment that the climate states were derived from and contributed to climate model development. VB contributed to methane module development. TK and VB planned the study; all authors discussed the analysis and the paper.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interests.

We acknowledge support through the project PalMod, funded by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF). Computational resources were made available by Deutsches Klimarechenzentrum (DKRZ). We thank Anne Dallmeyer for comments on an earlier version of the paper. We also thank two anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments.

This research has been supported by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) (grant no. 01LP1507B).

The article processing charges for this open-access publication were covered by the Max Planck Society.

This paper was edited by Ed Brook and reviewed by two anonymous referees.

Amante, C. and Eakins, B.: ETOPO1 1 Arc-Minute Global Relief Model: Procedures, Data Sources and Analysis, NOAA technical memorandum NESDIS NGDC-24, National Geophysical Data Center, NOAA, https://doi.org/10.7289/V5C8276M, 2009. a

Baumgartner, M., Schilt, A., Eicher, O., Schmitt, J., Schwander, J., Spahni, R., Fischer, H., and Stocker, T. F.: High-resolution interpolar difference of atmospheric methane around the Last Glacial Maximum, Biogeosciences, 9, 3961–3977, https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-9-3961-2012, 2012. a

Berger, A. L.: Long-Term Variations of Daily Insolation and Quaternary Climatic Changes, J. Atmos. Sci., 35, 2362–2367, https://doi.org/10.1175/1520-0469(1978)035<2362:LTVODI>2.0.CO;2, 1978. a

Beven, K. J. and Kirkby, M. J.: A physically based, variable contributing area model of basin hydrology, Hydrol. Sci. B., 24, 43–69, 1979. a

Bock, M., Schmitt, J., Beck, J., Seth, B., Chappellaz, J., and Fischer, H.: Glacial/interglacial wetland, biomass burning, and geologic methane emissions constrained by dual stable isotopic CH4 ice core records, P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 114, E5778–E5786, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1613883114, 2017. a

Bousquet, P., Ringeval, B., Pison, I., Dlugokencky, E. J., Brunke, E.-G., Carouge, C., Chevallier, F., Fortems-Cheiney, A., Frankenberg, C., Hauglustaine, D. A., Krummel, P. B., Langenfelds, R. L., Ramonet, M., Schmidt, M., Steele, L. P., Szopa, S., Yver, C., Viovy, N., and Ciais, P.: Source attribution of the changes in atmospheric methane for 2006–2008, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 11, 3689–3700, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-11-3689-2011, 2011. a, b

Briggs, R. D., Pollard, D., and Tarasov, L.: A data-constrained large ensemble analysis of Antarctic evolution since the Eemian, Quaternary Sci. Rev., 103, 91–115, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2014.09.003, 2014. a

Brovkin, V., Boysen, L., Raddatz, T., Gayler, V., Loew, A., and Claussen, M.: Evaluation of vegetation cover and land-surface albedo in MPI-ESM CMIP5 simulations, J. Adv. Model. Earth Syst., 5, 48–57, https://doi.org/10.1029/2012MS000169, 2013. a

Buytaert, W.: Topmodel, available at: http://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/topmodel/index.html (last access: 21 December 2016), 2011. a

Chappellaz, J. A., Fung, I. Y., and Thompson, A. M.: The atmospheric CH4 increase since the Last Glacial Maximum, Tellus B, 45, 228–241, https://doi.org/10.3402/tellusb.v45i3.15726, 1993. a

Dlugokencky, E. J., Masarie, K. A., Lang, P. M., and Tans, P. P.: Continuing decline in the growth rate of the atmospheric methane burden, Nature, 393, 447–450, https://doi.org/10.1038/30934, 1998. a

Gedney, N. and Cox, P. M.: The Sensitivity of Global Climate Model Simulations to the Representation of Soil Moisture Heterogeneity, J. Hydrometeorol., 4, 1265–1275, https://doi.org/10.1175/1525-7541(2003)004<1265:TSOGCM>2.0.CO;2, 2003. a

Giorgetta, M. A., Jungclaus, J., Reick, C. H., Legutke, S., Bader, J., Böttinger, M., Brovkin, V., Crueger, T., Esch, M., Fieg, K., Glushak, K., Gayler, V., Haak, H., Hollweg, H.-D., Ilyina, T., Kinne, S., Kornblueh, L., Matei, D., Mauritsen, T., Mikolajewicz, U., Mueller, W., Notz, D., Pithan, F., Raddatz, T., Rast, S., Redler, R., Roeckner, E., Schmidt, H., Schnur, R., Segschneider, J., Six, K. D., Stockhause, M., Timmreck, C., Wegner, J., Widmann, H., Wieners, K.-H., Claussen, M., Marotzke, J., and Stevens, B.: Climate and carbon cycle changes from 1850 to 2100 in MPI-ESM simulations for the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project phase 5, J. Adv. Model. Earth Syst., 5, 572–597, https://doi.org/10.1002/jame.20038, 2013. a

Goll, D. S., Brovkin, V., Liski, J., Raddatz, T., Thum, T., and Todd-Brown, K. E. O.: Strong dependence of CO2 emissions from anthropogenic land cover change on initial land cover and soil carbon parametrization, Global Biogeochem. Cycles, 29, 1511–1523, https://doi.org/10.1002/2014GB004988, 2015. a, b

Hagemann, S. and Stacke, T.: Impact of the soil hydrology scheme on simulated soil moisture memory, Clim. Dyna., 44, 1731–1750, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00382-014-2221-6, 2015. a

Hopcroft, P. O., Valdes, P. J., O'Connor, F. M., Kaplan, J. O., and Beerling, D. J.: Understanding the glacial methane cycle, Nat. Commun., 8, 14383, https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms14383, 2017. a, b

Huybers, P. and Langmuir, C.: Feedback between deglaciation, volcanism, and atmospheric CO2, Earth Planet. Sci. Lett., 286, 479–491, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2009.07.014, 2009. a

Ivanovic, R. F., Gregoire, L. J., Kageyama, M., Roche, D. M., Valdes, P. J., Burke, A., Drummond, R., Peltier, W. R., and Tarasov, L.: Transient climate simulations of the deglaciation 21–9 thousand years before present (version 1) – PMIP4 Core experiment design and boundary conditions, Geosci. Model Dev., 9, 2563–2587, https://doi.org/10.5194/gmd-9-2563-2016, 2016. a

Jackson, R. B., Canadell, J., Ehleringer, J. R., Mooney, H. A., Sala, O. E., and Schulze, E. D.: A global analysis of root distributions for terrestrial biomes, Oecologia, 108, 389–411, https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00333714, 1996. a

Kaiser, J. W., Heil, A., Andreae, M. O., Benedetti, A., Chubarova, N., Jones, L., Morcrette, J.-J., Razinger, M., Schultz, M. G., Suttie, M., and van der Werf, G. R.: Biomass burning emissions estimated with a global fire assimilation system based on observed fire radiative power, Biogeosciences, 9, 527–554, https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-9-527-2012, 2012. a

Kaplan, J. O.: Wetlands at the Last Glacial Maximum: Distribution and methane emissions, Geophys. Res. Lett., 29, 1079, https://doi.org/10.1029/2001GL013366, 2002. a

Kaplan, J. O., Folberth, G., and Hauglustaine, D. A.: Role of methane and biogenic volatile organic compound sources in late glacial and Holocene fluctuations of atmospheric methane concentrations, Global Biogeochem. Cycles, 20, GB2016, https://doi.org/10.1029/2005GB002590, 2006. a

Kinne, S., O'Donnel, D., Stier, P., Kloster, S., Zhang, K., Schmidt, H., Rast, S., Giorgetta, M., Eck, T. F., and Stevens, B.: MAC-v1: A new global aerosol climatology for climate studies, J. Adv. Model. Earth Syst., 5, 704–740, https://doi.org/10.1002/jame.20035, 2013. a

Kirschke, S., Bousquet, P., Ciais, P., Saunois, M., Canadell, J. G., Dlugokencky, E. J., Bergamaschi, P., Bergmann, D., Blake, D. R., Bruhwiler, L., Cameron-Smith, P., Castaldi, S., Chevallier, F., Feng, L., Fraser, A., Heimann, M., Hodson, E. L., Houweling, S., Josse, B., Fraser, P. J., Krummel, P. B., Lamarque, J.-F., Langenfelds, R. L., Le Quere, C., Naik, V., O'Doherty, S., Palmer, P. I., Pison, I., Plummer, D., Poulter, B., Prinn, R. G., Rigby, M., Ringeval, B., Santini, M., Schmidt, M., Shindell, D. T., Simpson, I. J., Spahni, R., Steele, L. P., Strode, S. A., Sudo, K., Szopa, S., van der Werf, G. R., Voulgarakis, A., van Weele, M., Weiss, R. F., Williams, J. E., and Zeng, G.: Three decades of global methane sources and sinks, Nat. Geosci., 6, 813–823, 2013. a, b

Köhler, P., Nehrbass-Ahles, C., Schmitt, J., Stocker, T. F., and Fischer, H.: A 156 kyr smoothed history of the atmospheric greenhouse gases CO2, CH4, and N2O and their radiative forcing, Earth Syst. Sci. Data, 9, 363–387, https://doi.org/10.5194/essd-9-363-2017, 2017. a, b, c

Lasslop, G., Thonicke, K., and Kloster, S.: SPITFIRE within the MPI Earth system model: Model development and evaluation, J. Adv. Model. Earth Syst., 6, 740–755, https://doi.org/10.1002/2013MS000284, 2014. a, b, c

Levine, J. G., Wolff, E. W., Jones, A. E., Sime, L. C., Valdes, P. J., Archibald, A. T., Carver, G. D., Warwick, N. J., and Pyle, J. A.: Reconciling the changes in atmospheric methane sources and sinks between the Last Glacial Maximum and the pre-industrial era, Geophys. Res. Lett., 38, L23804, https://doi.org/10.1029/2011GL049545, 2011. a

Marthews, T. R., Dadson, S. J., Lehner, B., Abele, S., and Gedney, N.: High-resolution global topographic index values for use in large-scale hydrological modelling, Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci., 19, 91–104, https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-19-91-2015, 2015. a

Mauritsen, T., Bader, J., Becker, T., Behrens, J., Bittner, M., Brokopf, R., Brovkin, V., Claussen, M., Crueger, T., Esch, M., Fast, I., Fiedler, S., Fläschner, D., Gayler, V., Giorgetta, M., Goll, D. S., Haak, H., Hagemann, S., Hedemann, C., Hohenegger, C., Ilyina, T., Jahns, T., Jimenéz-de-la Cuesta, D., Jungclaus, J., Kleinen, T., Kloster, S., Kracher, D., Kinne, S., Kleberg, D., Lasslop, G., Kornblueh, L., Marotzke, J., Matei, D., Meraner, K., Mikolajewicz, U., Modali, K., Möbis, B., Müller, W. A., Nabel, J. E. M. S., Nam, C. C. W., Notz, D., Nyawira, S.-S., Paulsen, H., Peters, K., Pincus, R., Pohlmann, H., Pongratz, J., Popp, M., Raddatz, T. J., Rast, S., Redler, R., Reick, C. H., Rohrschneider, T., Schemann, V., Schmidt, H., Schnur, R., Schulzweida, U., Six, K. D., Stein, L., Stemmler, I., Stevens, B., von Storch, J.-S., Tian, F., Voigt, A., Vrese, P., Wieners, K.-H., Wilkenskjeld, S., Winkler, A., and Roeckner, E.: Developments in the MPI-M Earth System Model version 1.2 (MPI-ESM1.2) and its response to increasing CO2, J. Adv. Model. Earth Syst., 11, 998–1038, https://doi.org/10.1029/2018MS001400, 2019. a, b

Meccia, V. L. and Mikolajewicz, U.: Interactive ocean bathymetry and coastlines for simulating the last deglaciation with the Max Planck Institute Earth System Model (MPI-ESM-v1.2), Geosci. Model Dev., 11, 4677–4692, https://doi.org/10.5194/gmd-11-4677-2018, 2018. a

Melton, J. R., Wania, R., Hodson, E. L., Poulter, B., Ringeval, B., Spahni, R., Bohn, T., Avis, C. A., Beerling, D. J., Chen, G., Eliseev, A. V., Denisov, S. N., Hopcroft, P. O., Lettenmaier, D. P., Riley, W. J., Singarayer, J. S., Subin, Z. M., Tian, H., Zürcher, S., Brovkin, V., van Bodegom, P. M., Kleinen, T., Yu, Z. C., and Kaplan, J. O.: Present state of global wetland extent and wetland methane modelling: conclusions from a model inter-comparison project (WETCHIMP), Biogeosciences, 10, 753–788, https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-10-753-2013, 2013. a

Mikolajewicz, U., Ziemen, F., Cioni, G., Claussen, M., Fraedrich, K., Heidkamp, M., Hohenegger, C., Jimenez de la Cuesta, D., Kapsch, M.-L., Lemburg, A., Mauritsen, T., Meraner, K., Röber, N., Schmidt, H., Six, K. D., Stemmler, I., Tamarin-Brodsky, T., Winkler, A., Zhu, X., and Stevens, B.: The climate of a retrograde rotating Earth, Earth Syst. Dynam., 9, 1191–1215, https://doi.org/10.5194/esd-9-1191-2018, 2018. a, b, c

Mitchell, L., Brook, E., Lee, J. E., Buizert, C., and Sowers, T.: Constraints on the Late Holocene Anthropogenic Contribution to the Atmospheric Methane Budget, Science, 342, 964–966, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1238920, 2013. a

Monfreda, C., Ramankutty, N., and Foley, J. A.: Farming the planet: 2. Geographic distribution of crop areas, yields, physiological types, and net primary production in the year 2000, Global Biogeochem. Cycles, 22, GB1022, https://doi.org/10.1029/2007GB002947, 2008. a

Murray, L. T., Mickley, L. J., Kaplan, J. O., Sofen, E. D., Pfeiffer, M., and Alexander, B.: Factors controlling variability in the oxidative capacity of the troposphere since the Last Glacial Maximum, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 14, 3589–3622, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-14-3589-2014, 2014. a

Petrenko, V. V., Smith, A. M., Schaefer, H., Riedel, K., Brook, E., Baggenstos, D., Harth, C., Hua, Q., Buizert, C., Schilt, A., Fain, X., Mitchell, L., Bauska, T., Orsi, A., Weiss, R. F., and Severinghaus, J. P.: Minimal geological methane emissions during the Younger Dryas–Preboreal abrupt warming event, Nature, 548, 443–446, 2017. a, b

Poulter, B., Bousquet, P., Canadell, J. G., Ciais, P., Peregon, A., Saunois, M., Arora, V. K., Beerling, D. J., Brovkin, V., Jones, C. D., Joos, F., Gedney, N., Ito, A., Kleinen, T., Koven, C. D., McDonald, K., Melton, J. R., Peng, C., Peng, S., Prigent, C., Schroeder, R., Riley, W. J., Saito, M., Spahni, R., Tian, H., Taylor, L., Viovy, N., Wilton, D., Wiltshire, A., Xu, X., Zhang, B., Zhang, Z., and Zhu, Q.: Global wetland contribution to 2000–2012 atmospheric methane growth rate dynamics, Environ. Res. Lett., 12, 094013, https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/aa8391, 2017. a

Prigent, C., Papa, F., Aires, F., Jimenez, C., Rossow, W. B., and Matthews, E.: Changes in land surface water dynamics since the 1990s and relation to population pressure, Geophys. Res. Lett., 39, L08403, https://doi.org/10.1029/2012GL051276, 2012. a, b, c, d, e, f, g, h

Reick, C. H., Raddatz, T., Brovkin, V., and Gayler, V.: Representation of natural and anthropogenic land cover change in MPI-ESM, J. Adv. Model. Earth Syst., 5, 459–482, https://doi.org/10.1002/jame.20022, 2013. a

Riddick, T., Brovkin, V., Hagemann, S., and Mikolajewicz, U.: Dynamic hydrological discharge modelling for coupled climate model simulations of the last glacial cycle: the MPI-DynamicHD model version 3.0, Geosci. Model Dev., 11, 4291–4316, https://doi.org/10.5194/gmd-11-4291-2018, 2018. a

Riley, W. J., Subin, Z. M., Lawrence, D. M., Swenson, S. C., Torn, M. S., Meng, L., Mahowald, N. M., and Hess, P.: Barriers to predicting changes in global terrestrial methane fluxes: analyses using CLM4Me, a methane biogeochemistry model integrated in CESM, Biogeosciences, 8, 1925–1953, https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-8-1925-2011, 2011. a, b

Saunois, M., Bousquet, P., Poulter, B., Peregon, A., Ciais, P., Canadell, J. G., Dlugokencky, E. J., Etiope, G., Bastviken, D., Houweling, S., Janssens-Maenhout, G., Tubiello, F. N., Castaldi, S., Jackson, R. B., Alexe, M., Arora, V. K., Beerling, D. J., Bergamaschi, P., Blake, D. R., Brailsford, G., Brovkin, V., Bruhwiler, L., Crevoisier, C., Crill, P., Covey, K., Curry, C., Frankenberg, C., Gedney, N., Höglund-Isaksson, L., Ishizawa, M., Ito, A., Joos, F., Kim, H.-S., Kleinen, T., Krummel, P., Lamarque, J.-F., Langenfelds, R., Locatelli, R., Machida, T., Maksyutov, S., McDonald, K. C., Marshall, J., Melton, J. R., Morino, I., Naik, V., O'Doherty, S., Parmentier, F.-J. W., Patra, P. K., Peng, C., Peng, S., Peters, G. P., Pison, I., Prigent, C., Prinn, R., Ramonet, M., Riley, W. J., Saito, M., Santini, M., Schroeder, R., Simpson, I. J., Spahni, R., Steele, P., Takizawa, A., Thornton, B. F., Tian, H., Tohjima, Y., Viovy, N., Voulgarakis, A., van Weele, M., van der Werf, G. R., Weiss, R., Wiedinmyer, C., Wilton, D. J., Wiltshire, A., Worthy, D., Wunch, D., Xu, X., Yoshida, Y., Zhang, B., Zhang, Z., and Zhu, Q.: The global methane budget 2000–2012, Earth Syst. Sci. Data, 8, 697–751, https://doi.org/10.5194/essd-8-697-2016, 2016. a, b, c, d, e, f, g, h, i, j, k, l, m

Schneck, R., Reick, C. H., and Raddatz, T.: Land contribution to natural CO2 variability on time scales of centuries, J. Adv. Model. Earth Syst., 5, 354–365, https://doi.org/10.1002/jame.20029, 2013. a

Schroeder, R., McDonald, K. C., Chapman, B. D., Jensen, K., Podest, E., Tessler, Z. D., Bohn, T. J., and Zimmermann, R.: Development and Evaluation of a Multi-Year Fractional Surface Water Data Set Derived from Active/Passive Microwave Remote Sensing Data, Remote Sens., 7, 15843, https://doi.org/10.3390/rs71215843, 2015. a

Singarayer, J. S., Valdes, P. J., Friedlingstein, P., Nelson, S., and Beerling, D. J.: Late Holocene methane rise caused by orbitally controlled increase in tropical sources, Nature, 470, 82–85, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature09739, 2011. a, b

Sitch, S., Smith, B., Prentice, I. C., Arneth, A., Bondeau, A., Cramer, W., Kaplan, J. O., Levis, S., Lucht, W., Sykes, M. T., Thonicke, K., and Venevsky, S.: Evaluation of ecosystem dynamics, plant geography and terrestrial carbon cycling in the LPJ dynamic global vegetation model, Global Change Biol., 9, 161–185, 2003. a

Sivapalan, M., Beven, K., and Wood, E. F.: On Hydrologic Similarity. 2. A Scaled Model of Storm Runoff Production, Water Resour. Res., 23, 2266–2278, https://doi.org/10.1029/WR023i012p02266, 1987. a

Stevens, B., Fiedler, S., Kinne, S., Peters, K., Rast, S., Müsse, J., Smith, S. J., and Mauritsen, T.: MACv2-SP: a parameterization of anthropogenic aerosol optical properties and an associated Twomey effect for use in CMIP6, Geosci. Model Dev., 10, 433–452, https://doi.org/10.5194/gmd-10-433-2017, 2017. a

Stocker, B. D., Spahni, R., and Joos, F.: DYPTOP: a cost-efficient TOPMODEL implementation to simulate sub-grid spatio-temporal dynamics of global wetlands and peatlands, Geosci. Model Dev., 7, 3089–3110, https://doi.org/10.5194/gmd-7-3089-2014, 2014. a

Tarasov, L., Dyke, A. S., Neal, R. M., and Peltier, W.: A data-calibrated distribution of deglacial chronologies for the North American ice complex from glaciological modeling, Earth Plane. Sc. Lett., 315–316, 30–40, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2011.09.010, 2012. a

Thonicke, K., Spessa, A., Prentice, I. C., Harrison, S. P., Dong, L., and Carmona-Moreno, C.: The influence of vegetation, fire spread and fire behaviour on biomass burning and trace gas emissions: results from a process-based model, Biogeosciences, 7, 1991–2011, https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-7-1991-2010, 2010. a, b

Tuomi, M., Thum, T., Järvinen, H., Fronzek, S., Berg, B., Harmon, M., Trofymow, J., Sevanto, S., and Liski, J.: Leaf litter decomposition – Estimates of global variability based on Yasso07 model, Ecol. Model., 220, 3362–3371, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolmodel.2009.05.016, 2009. a

Valdes, P. J., Beerling, D. J., and Johnson, C. E.: The ice age methane budget, Geophys. Res. Lett., 32, L02704, https://doi.org/10.1029/2004GL021004, 2005. a

Wania, R., Ross, I., and Prentice, I. C.: Implementation and evaluation of a new methane model within a dynamic global vegetation model: LPJ-WHyMe v1.3.1, Geosci. Model Dev., 3, 565–584, https://doi.org/10.5194/gmd-3-565-2010, 2010. a

Weber, S. L., Drury, A. J., Toonen, W. H. J., and van Weele, M.: Wetland methane emissions during the Last Glacial Maximum estimated from PMIP2 simulations: Climate, vegetation, and geographic controls, J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos., 115, D06111, https://doi.org/10.1029/2009JD012110, 2010. a

Xu, X., Yuan, F., Hanson, P. J., Wullschleger, S. D., Thornton, P. E., Riley, W. J., Song, X., Graham, D. E., Song, C., and Tian, H.: Reviews and syntheses: Four decades of modeling methane cycling in terrestrial ecosystems, Biogeosciences, 13, 3735–3755, https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-13-3735-2016, 2016. a

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Model and experiments

- Results and discussion

- Conclusions

- Appendix A: Sensitivity of LGM wetland fluxes

- Appendix B: Overview over absolute emissions

- Code and data availability

- Author contributions

- Competing interests

- Acknowledgements

- Financial support

- Review statement

- References

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Model and experiments

- Results and discussion

- Conclusions

- Appendix A: Sensitivity of LGM wetland fluxes

- Appendix B: Overview over absolute emissions

- Code and data availability

- Author contributions

- Competing interests

- Acknowledgements

- Financial support

- Review statement

- References