the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Wet–dry status change in global closed basins between the mid-Holocene and the Last Glacial Maximum and its implication for future projection

Xinzhong Zhang

Yu Li

Wangting Ye

Simin Peng

Yuxin Zhang

Hebin Liu

Yichan Li

Qin Han

Lingmei Xu

Closed basins, mainly located in subtropical and temperate drylands, have experienced alarming declines in water storage in recent years. An assessment of long-term hydroclimate change in those regions remains unquantified at a global scale as of yet. By integrating lake records, PMIP3–CMIP5 simulations and modern observations, we assess the wet–dry status of global closed basins during the Last Glacial Maximum, mid-Holocene, pre-industrial, and 20th and 21st century periods. Results show comparable patterns of general wetter climate during the mid-Holocene and near-future warm period, mainly attributed to the boreal summer and winter precipitation increasing, respectively. The long-term pattern of moisture change is highly related to the high-latitude ice sheets and low-latitude solar radiation, which leads to the poleward moving of westerlies and strengthening of monsoons during the interglacial period. However, modern moisture changes show correlations with El Niño–Southern Oscillation in most closed basins, such as the opposite significant correlations between North America and southern Africa and between central Eurasia and Australia, indicating strong connection with ocean oscillation. The strategy for combating future climate change should be more resilient to diversified hydroclimate responses in different closed basins.

- Article

(2640 KB) - Full-text XML

-

Supplement

(187 KB) - BibTeX

- EndNote

A great number of observations in the last 100 years show that the Earth's climate is now experiencing significant change characterized by global warming (Hansen et al., 2010; Trenberth et al., 2013; Dai et al., 2015; Huang et al., 2016; Li et al., 2018), which is unequivocally induced by the increase in concentrations of greenhouse gases according to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC, 2013). Recent studies have indicated increasing drought and accelerated dryland expansion under modern global warming resulting from a higher vapour pressure deficit and evaporative demand (Dai, 2013; Feng and Fu, 2013; Huang et al., 2017). Assessing the impacts of global warming especially on the terrestrial moisture balance is not only one of the most important social and environmental issues but also the basis of future climate projections.

According to Held's hypothesis, rising atmospheric humidity will cause the existing patterns of atmospheric moisture divergence and convergence to intensify, thereby making effective precipitation more negative in the drylands and more positive in the tropics, now referred to as the “dry gets drier, wet gets wetter” (DGDWGW) paradigm (Held and Soden, 2006; Hu et al., 2019). However, this mechanism may be more complex regionally, especially over terrestrial environments, where wet–dry pattern changes over the past decades and in future projections do not follow the proposed intensification trend (Greve et al. 2014; Roderick et al. 2014). To accurately project future terrestrial hydroclimatic changes, past climates may aid in understanding the regional nuances of the DGDWGW effect (Lowry and Morrill, 2019). Quade and Broecker (2009) have verified Held's hypothesis by taking the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM) as a reverse analogue for modern global warming and point out that the hydroclimate changes in subtropical regions are more complicated. Besides, the African Humid Period and a following mid-Holocene (MH) thermal maximum are also the focused key periods (Lézine et al., 2011), and related research proves that gradual climate forcing can result in rapid climate responses and a remarkable transformation of the hydrologic cycle (deMenocal and Tierney, 2012). Furthermore, Burke et al. (2018) compared the six warm periods in the past including the early Eocene, mid-Pliocene, last interglacial, mid-Holocene, pre-industrial (PI) and 20th century with the simulated future scenario to find the best analogue for near-future climate. A long-term and large-scale evaluation on global hydroclimate change is of vital significance for a comprehensive understanding of the impact of global warming and for future climate projections.

Closed basins account for about one-fifth of the global land areas and are mainly located in the arid and semi-arid climate zones. As there is no outlet or hydrological connection to the oceans, the terminal lakes function as the ocean for closed basins and concentrate the sedimentary information of the whole basin (Li et al., 2015), which makes them ideal candidates for studying the hydroclimate change of the past. Besides, they play an important role in mitigating global changes by influencing the trend and interannual variability of the terrestrial carbon sink (Ahlström et al., 2015; Li et al., 2017), though the hydrological cycle of the closed basins is fragile and sensitive to climate change. In the most recent IPCC sea level budgets, changes in terrestrial water storage driven by the climate have been assumed to be too small to be included (IPCC, 2013; Zhan et al., 2019). However, recent advances in gravity satellite measurement enabled a quantification that water storage in closed basins is declining at alarming rates, which not only exacerbates local water stress but also imposes excess water on exorheic basins, leading to a potential sea level rise that matches the contribution of nearly half of the land glacier retreat (excluding Greenland and Antarctica; Wurtsbaugh et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2018). The influence of global warming on water availability in closed basins is far more serious than that in other regions, and understanding the pattern and mechanism of hydroclimate change in the past and modern warm periods will be the key to assessing the impact of future climate change.

In this paper, we focus on the wet–dry status change between the LGM, MH and modern warm period in global closed basins to improve our knowledge of regional responses to climate change. Based on the lake records, modern observations and simulations of the key periods from the Paleoclimate Modelling Intercomparison Project Phase 3 (PMIP3) and Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 5 (CMIP5), an assessment of hydroclimate change at different timescales from the LGM to MH and from the PI to late 21st century is conducted. The possible linkages of these moisture change patterns and their underlying physical mechanisms are also discussed. This assessment is essential for future climate projection and regional water management, especially in the dry hinterland.

2.1 Water level and moisture change inferred from lake records

The following criteria were used for the selection of the proxy records in this study (Chen et al., 2015):

-

The proxies should be indicative of moisture changes.

-

The records should cover both the LGM and MH time slices.

-

The dominant driving mechanism of the variation in proxy records should be climatic changes.

-

The records should have a dating control level of 6 or better for the LGM and MH time slices according to the Cooperative Holocene Mapping (COHMAP) project dating scheme.

A dating control level of 6 for continuous sequences was based on the following criteria: bracketing dates, one within 6000 years and the other within 8000 years or one within 4000 years and the other within 10 000 years of the selected date (21 and 6 ka). The same control level applied to discontinuous sequences requires at least one date within 2000 years of the time being assessed (Street-Perrott et al., 1989; COHMAP Members, 1994; Lowry and Morrill, 2019).

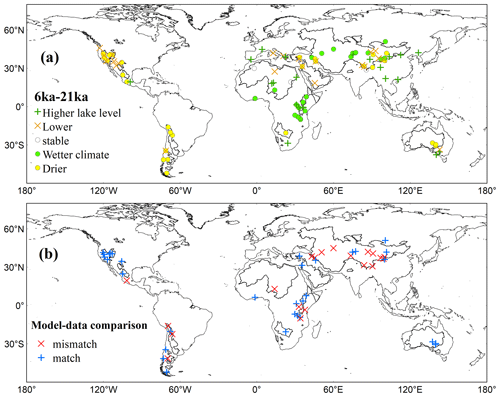

We then compared our new compilation of proxy records (Table S1 in the Supplement) to 50 water level records from the Global Lake Status Data Base (Street-Perrott et al., 1989; COHMAP Members, 1994; Harrison and Digerfeldt, 1993; Kohfeld and Harrison, 2000) and the Chinese Lake Status Data Base (Yu et al., 2001; Xue et al., 2017) in global closed basins and surrounding areas (Fig. 1). To capture the general spatial pattern, the differences of lake status between the LGM and MH in individual records were classified into three grades (higher–wetter, moderate, lower–drier). Similarly, the differences of simulated effective precipitation between the LGM and MH from PMIP3–CMIP5 multi-models in certain grids of the lake site were classified into positive, no change and negative and compared with the records.

2.2 Modern data sources and analyses

Closed-basin extents were acquired from HydroBASINS product, a series of polygon layers that depict watershed boundaries and sub-basin delineations at a global scale by using the HydroSHEDS (Hydrological data and maps based on SHuttle Elevation Derivatives at multiple Scales) database at 15 arcsec resolution (Lehner and Grill, 2013). There were some exceptions we did not take them into account in this study:

-

Ten landlocked watersheds in the Inner Tibetan Plateau, northeastern China, Siberia and western United States were captured only in Global Drainage Basin Database (Masutomi et al., 2009; Wang et al., 2018).

-

Sporadic landlocked watersheds smaller than 100 km2, embedded in the exorheic regions, were not considered independent units.

-

Some of the contemporary endorheic watersheds were exorheic in the past, such as the Wuyuer River basin in northeastern China.

Primary variables of mean precipitation (P) and potential evapotranspiration (PET) from Climatic Research Unit Time Series version 4.01 (CRU TS4.01), a gridded time-series dataset of month-by-month variation in climate covering all land areas (excluding Antarctica) at 0.5∘ resolution over the period 1901–2016 (Harris et al., 2014), were used for modern climate analysis. The aridity index (AI), defined as the ratio of annual precipitation to annual potential evapotranspiration by the United Nations Environment Programme (Middleton and Thomas, 1997), was applied. Furthermore, to explore the possible relationship between the ocean and closed basins in modern times, we carried out the Pearson correlation analysis between monthly AI and multivariate El Niño–Southern Oscillation (ENSO) index (MEI; Kobayashi et al., 2015) and other indexes such as the North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO), Southern Oscillation Index (SOI), Pacific Decadal Oscillation (PDO) and Tripole Index for the Interdecadal Pacific Oscillation (TPI; Supplement Table S2) for different endorheic regions. Linear trend of AI change in global closed basins during 1979–2016 was provided, and a trend was considered statistically significant at a significance level of 5 %.

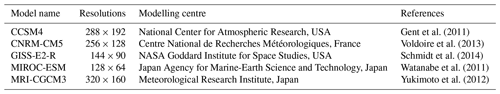

2.3 Debiasing and downscaling of PMIP3–CMIP5 multi-model ensemble

Experiments of the LGM, MH and PI from the PMIP3 and projection experiment of 21st century under Representative Concentration Pathway 8.5 (RCP8.5) from the CMIP5 were used in this study (Braconnot et al., 2012; Taylor et al., 2012). To ensure the consistency and precision of simulations as much as possible, we used the outputs from five global climate models (Table 1) which have all completed the above key period experiments at a spatial resolution of less than 3∘. The periods of 2006–2015 and 2091–2100 were defined as the representatives of early and late 21 century (E21 and L21), respectively.

Statistical downscaling and debiasing followed a multi-step approach described by Tabor and Williams (2010). The primary climate variables were first debiased by differencing each paleoclimate (LGM, MH, PI) or future climate (2017–2100) simulation from a present climate simulation (2006–2015). These anomalies are then downscaled through spline interpolation to a 0.5∘ resolution grid corresponding to the modern observational CRU dataset. The anomalies are then added to the observational data (2006–2015) to produce the debiased and downscaled primary variables for the paleoclimate or future climate simulation. This differencing removes any systematic difference as long as that bias is constant through time (Lorenz et al., 2016). The effective precipitation calculated by precipitation minus evaporation was introduced to compare with the lake status during the LGM and MH and predict future changes in moisture balance.

3.1 Wet–dry status changes from lake records

Generally, lake level changes match climate changes from the proxy records well except for central Asia (Fig. 1). In the North and South American continents, almost all closed basins experience a wetter LGM compared to the MH status, and the same situations exist in some closed basins of the eastern Mediterranean, Tibetan Plateau and Australia. On the contrary, eastern African highlands and the Sahel region show a prevailing wetter MH, which may be highly attributed to the African Humid Period. Changes in central Eurasia are more complicated. The monsoonal eastern Asia and arid central Asia both record wetter MH, while in the middle area between them, there are some contradictory records synchronously showing lower lake level and wetter climate. Though evidence from southern Africa and Australia are insufficient, several records tend to support a wetter LGM. Hereto, it is worth noting that there are two belt regions around latitude 30∘ in both hemispheres, where substantial high lake levels during the LGM disappeared or subsided during the MH. And the low-latitude Africa and mid-latitude Asia basically experienced an opposite pattern of a wetter MH.

Figure 1Wet–dry status changes between the LGM and MH from lake records (a) and comparison with the simulated effective precipitation from PMIP3–CMIP5 multi-models (b). The green and yellow cross sites are from lake status databases; the green and yellow point sites are from recently published literature; the hollow points indicate that there is no significant change in lake level or climate condition between the LGM and MH.

Comparison between the wet–dry status change from new compilation of proxy records and simulated effective precipitation from PMIP3–CMIP5 multi-models is shown in Fig. 1b. The model ensemble does particularly well in simulating the direction of hydroclimate change in most closed basins of Americas, Africa and Australia. The most mismatches exist in the central Eurasia, since many lake records suggest wetter climate during MH, whereas the model ensemble does not. Some minor mismatches occur in the eastern Africa and South America, where the altitude changes dramatically so that the models may appear to miss the details of climate change.

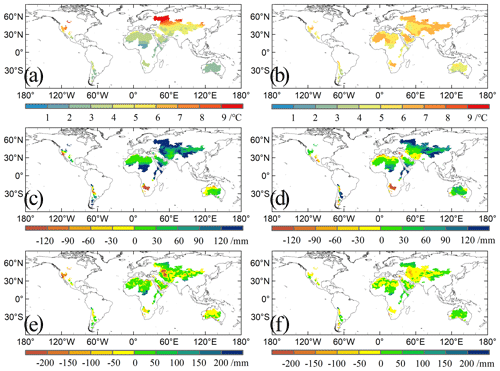

3.2 Simulated climate changes under the past and future warming

Spatial patterns of hydroclimate change for MH–LGM and L21–PI are shown in Fig. 2. It is apparent that the MH warming is characterized by strong latitudinal zonality, while future warming is more homogeneous over all closed basins. The temperature rise by the end of this century will exceed that during the period of LGM–MH in most closed basins under RCP8.5 scenario (excluding the high latitudes of North America and central Asia). On the contrary, precipitation increasing under future warming is lighter and keeps the similar distribution pattern of MH. The dramatic shifts of precipitation change between the two periods exist in the subtropics such as the dry–wet shifts in the Mediterranean coast, Mexican Plateau and Iranian Plateau. For the pattern of effective precipitation change, it is substantially fragmented. The prevailing wetter climate in northern Africa and central Eurasia during the MH is weakened, while Australia gets wetter in the future. As a consequence, the core area of drought is moved from western United States during the MH to central Asia by the end of this century.

Figure 2Annual mean temperature (a, b), precipitation (c, d) and effective precipitation (e, f) differences for MH–LGM (a, c, e) and L21–PI (b, d, f) in global closed basins based on the PMIP3–CMIP5 multi-model ensemble.

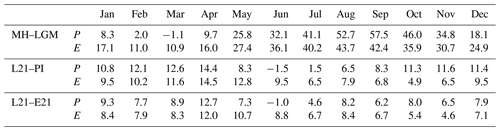

Table 2Percentage changes of monthly precipitation (P) and evaporation (E) between different periods from the multi-models.

To investigate the seasonal difference of hydroclimate change, we assess the percentage changes of monthly precipitation and evaporation during the MH, modern and future warm periods at a global scale (Table 2). It turns out that remarkable increases of precipitation and evaporation mainly occur in the boreal summer half-year during the MH, while in modern and future warm periods they are concentrated in the boreal winter half-year. The precipitation increases about 50 % from the LGM to the MH in the wettest months of July–October and 13 % from PI to L21 in the wettest months of February–April. Seasonal variation in evaporation is smaller than that in precipitation but keeps the same pattern. In addition, precipitation and evaporation changes from E21 to L21 make significant contributions to the increasing of precipitation and evaporation from PI to L21, especially in the boreal summer half-year.

3.3 Moisture trends and connections of modern observations

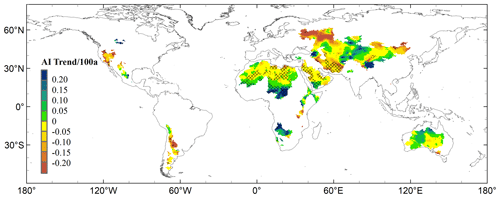

Over the past four decades, as shown in Fig. 3, about 70 % of the total areas of global closed basins are getting drier. The severe drying regions include the Great Basin and the Patagonia in Americas and the Upper Volga River basin and Iranian Plateau in central Eurasia. The wetting trends mainly occur in the low latitudes of Africa and the high altitudes of Asia including the Caucasus Mountains, the Tian Shan, the Pamir Mountains and Tibetan Plateau. Besides, the marginal closed basins of eastern Asia and northern Australia as well as the Mexican Plateau and the Altiplano in the Americas show lighter wetting trends. It is worth noting that the future pattern of effective precipitation change (Fig. 2f) mainly continues the trends of modern moisture change, with the most significant mismatch in southern Africa. That means the mechanism of future hydroclimate change likely stays the same as modern times in most closed basins.

Figure 3Linear trends of modern observational AI for the period of 1979–2016 in global closed basins. Gridded areas are where the trends are statistically significant at 5 % level.

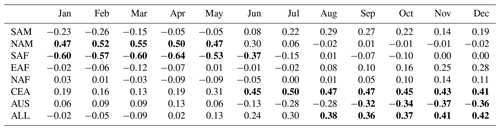

Table 3Pearson correlation coefficients between annual AI and monthly MEI during 1979–2016. The bold numbers mean that correlation coefficients are statistically significant at 5 % level. SAM – South America, NAM – North America, SAF – southern Africa, EAF – eastern Africa, NAF – northern Africa and Arabian peninsula, CEA – central Eurasia, AUS – Australia, ALL – global closed basins.

By calculating the Pearson correlation coefficients between annual AI and monthly MEI, NAO, SOI, PDO and TPI, we seek the potential connections of moisture change in closed basins with ocean oscillation. As a result, the performance of NAO, SOI and PDO is comparatively weak, and the MEI responds the best and shows a similar pattern to TPI, both indicating the dominant role of the Pacific Ocean oscillation in controlling the moisture change of global closed basins (Table 3, Table S2). For the global closed basins as a whole, the AI change is significantly positive related to monthly MEI from August to December, and the correlation coefficient reaches its highest in December of boreal winter season. As the biggest part of global closed basins, central Eurasia apparently contributed the most in this positive feedback. On the contrary, in the Australian closed basins it is slightly negatively correlated with monthly MEI during almost the same seasons. Among the seven separated endorheic regions, AI changes in South America, eastern Africa and northern Africa show no significant correlation with MEI at all. For the other four regions, they are seemingly coupled between North America and southern Africa and between central Eurasia and Australia with the opposite significant AI–MEI relationships. During the first half of the year, North America responds positively, whereas southern Africa shows a negative response to the MEI change. The same pattern turns to central Eurasia and Australia in the second half of the year. This provides a potential perspective on the teleconnections in different closed basins globally.

Closed basins are mainly located in subtropical and temperate drylands, where the hydroclimate changes deeply depend on the limited moisture transport via atmospheric circulation. Based on this, among the seven separated endorheic regions mentioned before, most of them can be divided into two parts: the westerlies-dominated area and the monsoon-influenced area, such as central Asia and eastern Asia in central Eurasia as well as the western United States and the Mexican Plateau in North America. Thus, their climate changes are strongly influenced by the interactions of mid-latitude westerlies and low-latitude monsoon especially on a long-term timescale (Li et al., 2013, 2017, 2020; Chen et al., 2019). On a shorter timescale of modern times, internal variability of climate system like the ocean oscillations rather than the external forcing plays a more important role in controlling the regional moisture change (Wang et al., 2018). Though the driving mechanism may be extensively changed, our results show that hydroclimate changes in some closed basins respond in the same pattern to the past and future warming, indicating deeper connections at different timescales. More importantly, the long-term hydroclimate change patterns provide the baseline for modern and future climate change assessment (IPCC, 2013).

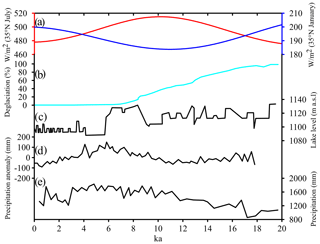

Figure 4Changes of insolation, ice sheet and typical lake records since the LGM. (a) Summer and winter insolation variations at 35∘ N (Laskar et al., 2004); (b) percent area change of ice sheets in North America (Dyke, 2004); (c) lake-level variation from Owens Lake, western USA (Bacon et al., 2020); (d) pollen-based annual mean precipitation record for lakes Dalianhai and Qinghai on the northeastern Tibetan Plateau, western China (Li et al., 2017); (e) pollen-based annual precipitation change (modern analogues technique) at Lake Barombi Mbo, northern Africa (Lebamba et al., 2012).

Previous studies have indicated that the hydroclimate change patterns in different latitudes at the millennial, centurial and decadal timescales show considerable connection with the general atmospheric circulation, which is mainly forced by the external forcing at a long-term timescale and by the internal factors of climate system at a shorter timescale (Kohfeld et al., 2013; Tierney et al., 2013; Ljungqvist et al., 2016; Zhang et al., 2017). From the perspective of paleoclimatology, the MH was extremely different from the LGM in the strengths and positions of monsoons and westerlies induced by the primary drivers such as solar insolation, Arctic warming and continental ice sheets (Sime et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2017; Bhattacharya et al., 2018; Routson et al., 2019; Jansen et al., 2020). Besides, it was also considered that the increase of atmospheric CO2 concentration and early human activities have been important driving forces for the changes of climate and lake level since the LGM (Shakun et al., 2010; Li et al., 2013; Miebach et al., 2016; Jenny et al., 2019). From the LGM to the early Holocene, it was characterized with retreat of continental ice sheets and increasing of summer insolation in the Northern Hemisphere (Fig. 4). During the LGM, the westerlies in the Northern Hemisphere moved south, reaching the southwest of the United States, the eastern Mediterranean region and southern Tibetan Plateau because of the development of continental ice sheets in the Northern Hemisphere such as the Laurentide Ice Sheet in North America (Rambeau, 2010; Lachniet et al., 2014; Lowry and Morrill, 2019; Batchelor et al., 2019). Also, the high winter insolation enhanced evaporation and moisture transport, resulting in higher winter precipitation compared to the MH. Thus, many lakes in western United States such as Owens Lake maintain high lake levels during the whole deglaciation period (Fig. 4c). On the contrary, summer insolation in the Northern Hemisphere reached its highest status during the early Holocene, leading to strengthening and expansion of monsoon by amplifying regional sea–land thermal contrast (An et al., 2000; Li and Harrison, 2008; Wang et al., 2017).

Evidence from paleoclimatic records and simulations in northern Africa had shown that the world's largest desert in modern times experienced a humid period and was covered by forests and lakes due to the strengthening of the African monsoon during the early and middle Holocene (Lézine et al., 2011; Lebamba et al., 2012; Contoux et al., 2013; Hély et al., 2014; Shanahan et al., 2015). And this kind of shifts was recorded in many monsoonal regions globally, including closed basins in Americas, Asia and Australia (Magee et al., 2004; Zhang et al., 2011; Kuhnt et al., 2015; Metcalfe et al., 2015; Bernal et al., 2016). As the most typical monsoon system, Asian summer monsoon even reached as far as the Tian Shan and Kunlun Mountains of central Asia during the Holocene (Wang et al., 2014; Ramisch et al., 2016), bringing monsoon precipitation and reforming the hydroclimate pattern in the eastern closed basins of central Eurasia. Even in modern times, the monsoon moisture could invade western Qilian Mountains and impact on precipitation especially the heavy-precipitation events (Du et al., 2020). However, from the LGM to MH, hydroclimate changes in central Eurasia were more complicated than that in other regions, due to the strong interactions of westerlies and monsoon in the middle region between the arid central Asia and monsoonal eastern Asia. As a consequence of moving of westerlies, the effective precipitation in arid central Asia did not increase until the middle and late Holocene, leading to a large number of low lake levels and showing different climate response pattern compared with that in monsoonal eastern Asia corresponding to the summer insolation change (Chen et al., 2008, 2019; Ran and Feng, 2013; Huang et al., 2014).

The difference in moisture change between the arid central Asia and monsoonal Asia still exists in modern times and near-future warm period, and it is more apparent between the high altitudes and lower basins from the modern observations (Fig. 3). On a shorter timescale of modern times, strengthening and moving of monsoons and westerlies are largely limited compared to that from the LGM to MH. As results have shown before, ocean oscillation – especially the Pacific Ocean oscillation – emphasizes its impact on controlling the moisture change of global closed basins, with two couples of the opposite significant AI–MEI relationships between North America and southern Africa and between central Eurasia and Australia (Table 3). The ENSO-based composite analyses have shown that the water vapour fluxes of seasonal precipitation in central Eurasia are mainly generated in Indian and North Atlantic oceans and transported by enhanced westerlies during El Niño events (Mariotti, 2007; Rana et al., 2017, 2019; Chen et al., 2018). Based on the simulation of future climate change, evidence shows that winter precipitation plays a dominant role in determining the wet–dry pattern change in global closed basins, implying the significance of westerlies instead of monsoons. These patterns provide some new perspectives to understand the differences and connections over global closed basins and remind us that we should focus more on the ocean oscillations in order to address the challenges of future climate change.

This study presents a new compilation of lake records and analyses of hydroclimate change at different timescales in global closed basins. Though it is well known that the forcing mechanisms between mid-Holocene and future warming are different, the patterns of hydroclimate changes of them show comparable spatial consistency in closed basins. From the LGM to the MH, the westerlies-dominated areas usually experience wet to dry shift, whereas the monsoon-influenced areas shift from drier to wetter climate. The hydroclimate changes from the PI to the late 21st century show similar patterns in most closed basins, except for central Asia, where it is wetter during the MH but drier during the future warm period. For the global closed basins as a whole, they are wetter both in the MH and L21 than during the LGM and PI. However, they are mainly attributed to the boreal summer and winter precipitation increasing, respectively. The seasonal difference of precipitation increasing indicates the different dominant roles of westerly winds and monsoons during the two periods. That is, the long-term regional differences of hydroclimate change are mainly controlled by the high-latitude ice sheets and low-latitude solar radiation, which leads to equatorward moving of the westerlies during the glacial period and the strengthening of monsoons during the interglacial period. An analysis of modern moisture change matching with the timescale of future warming suggests that it is related to ocean oscillations especially the Pacific Ocean oscillation, such as the two coupled opposite significant AI–MEI relationships between North America and southern Africa and between central Eurasia and Australia. Though the dryland expansion may be accelerated under the near-future warming in the hinterland globally, we cannot ignore the hydroclimate response differences within these regions, which largely affect the local strategies of economic development and environmental protection. We must be more resilient to tackle the future climate change corresponding to diversified hydroclimate changes in different closed basins.

Boundaries of closed basins are available from the Hydrological data and maps based on SHuttle Elevation Derivatives at multiple Scales (HydroSHEDS) website: https://www.hydrosheds.org/page/hydrobasins (last access: 28 October 2020; WWF, 2020). The Global Lake Status Data Base and the Chinese Lake Status Data Base are available from the Paleoclimatology Datasets of NOAA's National Centers for Environmental Information (NCEI): https://www.ncdc.noaa.gov/data-access/paleoclimatology-data/datasets (last access: 28 October 2020; NOAA, 2020). PMIP3–CMIP5 simulations are available from the Earth System Grid Federation (ESGF) Peer-to-Peer (P2P) enterprise system website: https://esgf-node.llnl.gov/projects/esgf-llnl/ (last access: 28 October 2020; Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, 2020). CRU TS4.01 data are available from https://crudata.uea.ac.uk/cru/data/hrg/ (last access: 28 October 2020; Climatic Research Unit, 2020). The values of MEI, NAO, SOI, PDO and TPI are available from https://psl.noaa.gov/data/climateindices/list/ (last access: 28 October 2020, Physical Sciences Laboratory, 2020). Details about the new compilation of proxy records are available in the Supplement.

The supplement related to this article is available online at: https://doi.org/10.5194/cp-16-1987-2020-supplement.

YL and XZ designed this study and carried it out. WY, YZ and SP contributed to the data processing, analysis and discussion of results. XZ prepared the manuscript with contributions from all co-authors.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest

We acknowledge Keely Mills, Cody Routson and one anonymous reviewer for constructive comments.

This research has been supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant nos. 42077415, 41822708), the Second Tibetan Plateau Scientific Expedition and Research Program (STEP) (grant no. 2019QZKK0202), and the Strategic Priority Research Program of Chinese Academy of Sciences (grant no. XDA20100102).

This paper was edited by Keely Mills and reviewed by Cody Routson and one anonymous referee.

Ahlström, A., Raupach, M. R., Schurgers, G., Smith, B., Arneth, A., Jung, M., Reichstein, M., Canadell, J. G., Friedlingstein, P., Jain, A. K., Kato, E., Poulter, B., Sitch, S., Stocker, B. D., Viovy, N., Wang, Y., Wiltshire, A., Zaehle, S., and Zeng, N.: The dominant role of semi-arid ecosystems in the trend and variability of the land CO2 sink, Science, 348, 895–899, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aaa1668, 2015.

An, Z., Porter, S. C., Kutzbach, J. E., Wu, X., Wang, S., Liu, X., Li, X., and Zhou, W.: Asynchronous Holocene optimum of the East Asian monsoon, Quaternary Sci. Rev., 19, 743–762, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0277-3791(99)00031-1, 2000.

Bacon, S., Jayko, A., Owen, L., Lindvall, S., Rhodes, E., Schumer, R., and Decker, D.: A 50,000-year record of lake-level variations and overflow from Owens Lake, eastern California, USA, Quaternary Sci. Rev., 238, 106312, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2020.106312, 2020.

Batchelor, C. L., Margold, M., Krapp, M., Murton, D. K., Dalton, A. S., Gibbard, P. L., Stokes, C. R., Murton, J. B., and Manica, A.:. The configuration of Northern Hemisphere ice sheets through the Quaternary, Nat. Commun., 10, 1–10, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-11601-2, 2019.

Bernal, J. P., Cruz, F. W., Stríkis, N. M., Wang, X., Deininger, M., Catunda, M. C. A., Ortega-Obregóna, C., Cheng, H., Edwards, R. L., and Auler, A. S.: High-resolution Holocene South American monsoon history recorded by a speleothem from Botuverá Cave, Brazil, Earth Planet. Sci. Lett., 450, 186–196, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2016.06.008, 2016.

Bhattacharya, T., Tierney, J. E., Addison, J. A., and Murray, J. W.: Ice-sheet modulation of deglacial North American monsoon intensification, Nat. Geosci., 11, 848–852, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41561-018-0220-7, 2018.

Braconnot, P., Harrison, S. P., Kageyama, M., Bartlein, P. J., Masson-Delmotte, V., Abe-Ouchi, A., and Zhao, Y.: Evaluation of climate models using palaeoclimatic data, Nat. Clim. Chang., 2, 417–424, https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate1456, 2012.

Burke, K. D., Williams, J. W., Chandler, M. A., Haywood, A. M., Lunt, D. J., and Otto-Bliesner, B. L.: Pliocene and Eocene provide best analogs for near-future climates, P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA., 115, 13288–13293, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1809600115, 2018.

Chen, F., Yu, Z., Yang, M., Ito, E., Wang, S., Madsen, D. B., and Boomer, I.: Holocene moisture evolution in arid central Asia and its out-of-phase relationship with Asian monsoon history, Quaternary Sci. Rev., 27, 351–364, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2007.10.017, 2008.

Chen, F., Chen, J., Huang, W., Chen, S., Huang, X., Jin, L., Jia, J., Zhang, X., An, C., Zhang, J., Zhao, Y., Yu, Z., Zhang, R., Liu, J., Zhou, A., and Feng, S.: Westerlies Asia and monsoonal Asia: Spatiotemporal differences in climate change and possible mechanisms on decadal to sub-orbital timescales, Earth-Sci. Rev., 192, 337–354, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earscirev.2019.03.005, 2019.

Chen, J., Chen, F., Feng, S., Huang, W., Liu, J., and Zhou, A.: Hydroclimatic changes in China and surroundings during the Medieval Climate Anomaly and Little Ice Age: spatial patterns and possible mechanisms, Quaternary Sci. Rev., 107, 98–111, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2014.10.012, 2015.

Chen, X., Wang, S., Hu, Z., Zhou, Q., and Qi, H.: Spatiotemporal characteristics of seasonal precipitation and their relationships with enso in central asia during 1901–2013, J. Geogr. Sci., 28, 1341–1368, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11442-018-1529-2, 2018.

Climatic Research Unit: High-resolution gridded datasets (and derived products), available at: https://crudata.uea.ac.uk/cru/data/hrg/, last access: 28 October 2020.

COHMAP Members: Oxford Lake Levels Database, IGBP PAGES/World Data Center- A for Paleoclimatology Data Contribution Series # 94-028, NOAA/NGDC Paleoclimatology Program, Boulder CO, USA, 1994.

Contoux, C., Jost, A., Ramstein, G., Sepulchre, P., Krinner, G., and Schuster, M.: Megalake Chad impact on climate and vegetation during the late Pliocene and the mid-Holocene, Clim. Past, 9, 1417–1430, https://doi.org/10.5194/cp-9-1417-2013, 2013.

Dai, A.: Increasing drought under global warming in observations and models, Nat. Clim. Chang., 3, 52–58, https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate1633, 2013.

Dai, A., Fyfe, J. C., Xie, S. P., and Dai, X.: Decadal modulation of global surface temperature by internal climate variability, Nat. Clim. Chang., 5, 555–559, https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate2605, 2015.

deMenocal, P. B. and Tierney, J. E.: Green Sahara: African Humid Periods Paced by Earth's Orbital Changes, Nature Education Knowledge, 3, 1–6, 2012.

Du, W., Kang, S., Qin, X., Ji, Z., Sun, W., Chen, J., Yang, J., and Chen, D.: Can summer monsoon moisture invade the Jade Pass in Northwestern China? Clim. Dynam., 55, 3101–3115, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00382-020-05423-y, 2020.

Dyke, A. S.: An outline of North American deglaciation with emphasis on central and northern Canada, in: Developments in Quaternary Sciences, edited by: Ehlers, J. and Gibbard, P. L., 373–424, https://doi.org/10.1016/s1571-0866(04)80209-4, 2004.

Feng, S. and Fu, Q.: Expansion of global drylands under a warming climate, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 13, 10081–10094, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-13-10081-2013, 2013.

Gent, P. R., Danabasoglu, G., Donner, L. J., Holland, M. M., Hunke, E. C., Jayne, S. R., Lawrence, D. M., Neale, R. B., Rasch, P. J., and Vertenstein, M.: The community climate system model version 4, J. Climate., 24, 4973–4991, https://doi.org/10.1175/2011JCLI4083.1, 2011.

Greve, P., Orlowsky, B., Mueller, B., Sheffield, J., Reichstein, M., and Seneviratne, S. I.: Global assessment of trends in wetting and drying over land, Nat. Geosci., 7, 716–721, https://doi.org/10.1038/ngeo2247, 2014.

Hansen, J., Ruedy, R., Sato, M., and Lo, K.: Global surface temperature change, Rev. Geophys., 48, RG4004, https://doi.org/10.1029/2010RG000345, 2010.

Harris, I., Jones, P. D., Osborn, T. J., and Lister, D. H.: Updated high-resolution grids of monthly climatic observations – the CRU TS3.10 Dataset, Int. J. Climatol., 34, 623–642, https://doi.org/10.1002/joc.3711, 2014.

Harrison, S. P. and Digerfeldt, G.: European lakes as paleohydrological and paleoclimatic indicators, Quaternary Sci. Rev., 12, 233–248, https://doi.org/10.1016/0277-3791(93)90079-2, 1993.

Held, I. M. and Soden, B. J.: Robust responses of the hydrological cycle to global warming, J. Climate., 19, 5686–5699, https://doi.org/10.1175/jcli3990.1, 2006.

Hély, C., Lézine, A.-M., and contributors, A.: Holocene changes in African vegetation: tradeoff between climate and water availability, Clim. Past, 10, 681–686, https://doi.org/10.5194/cp-10-681-2014, 2014.

Hu, Z., Chen, X., Chen, D., Li, J., Wang, S., Zhou, Q., Yin, G., and Guo, M.: “Dry gets drier, wet gets wetter”: A case study over the arid regions of central Asia, Int. J. Climatol., 39, 1072–1091, https://doi.org/10.1002/joc.5863, 2019.

Huang, J., Yu, H., Guan, X., Wang, G., and Guo, R.: Accelerated dryland expansion under climate change, Nat. Clim. Chang., 6, 166–171, https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate2837, 2016.

Huang, J., Li, Y., Fu, C., Chen, F., Fu, Q., Dai, A., Shinoda, M., Ma, Z., Guo, W., Li, Z., Zhang, L., Liu, Y., Yu, H., He, Y., Xie, Y., Guan, X., Ji, M., Lin, L., Wang, S., Yan, H., and Wang, G.: Dryland climate change: Recent progress and challenges, Rev. Geophys., 55, 719–778, https://doi.org/10.1002/2016rg000550, 2017.

Huang, X., Oberhansli, H., Von Suchodoletz, H., Prasad, S., Sorrel, P., Plessen, B., Mathis, M., and Usubaliev, R.: Hydrological changes in western Central Asia (Kyrgyzstan) during the Holocene as inferred from a palaeolimnological study in lake Son Kul, Quaternary Sci. Rev., 103, 134–152, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2014.09.012, 2014.

IPCC: Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis, Contribution of Working Group I to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom, 2013.

Jansen, E., Christensen, J. H., Dokken, T., Nisancioglu, K. H., Vinther, B. M., Capron, E., Guo, C., Jensen, M. F., Langen, P. L., Pedersen, R. A., Yang, S., Bentsen, M., Kjær, H. A., Sadatzki, H., Sessford, E., and Stendel, M.: Past perspectives on the present era of abrupt Arctic climate change, Nat. Clim. Chang., 10, 714–721, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-020-0860-7, 2020.

Jenny, J. P., Koirala, S., Gregory-Eaves, I., Francus, P., Niemann, C., Ahrens, B., Brovkin, V., Baud, A., Ojala, A., Normandeau, A., Zolitschka, B., and Carvalhais, N.: Human and climate global-scale imprint on sediment transfer during the Holocene, P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA., 116, 22972–22976, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1908179116, 2019.

Kobayashi, S., Ota, Y., Harada, Y., Ebita, A., Moriya, M., Onoda, H., Onogi, K., Kamahori, H., Kobayashi, C., Endo, H., Miyaoka, K., and Takahashi, K.: The JRA-55 Reanalysis: general specifications and basic characteristics, J. Meteorol. Soc. Jpn., 93, 5–48, https://doi.org/10.2151/jmsj.2015-001, 2015.

Kohfeld, K. E. and Harrison, S. P.: How well can we simulate past climates? Evaluating the models using global palaeoenvironmental datasets, Quaternary Sci. Rev., 19, 321–346, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0277-3791(99)00068-2, 2000.

Kohfeld, K. E., Graham, R. M., Boer, A. M. D., Sime, L. C., Wolff, E. W., Quéré, C. L., and Boop, L.: Southern hemisphere westerly wind changes during the last glacial maximum: paleo-data synthesis, Quaternary Sci. Rev., 68, 76–95, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2013.01.017, 2013.

Kuhnt, W., Holbourn, A., Xu, J., Opdyke, B., De Deckker, P., Röhl, U., and Mudelsee, M.: Southern Hemisphere control on Australian monsoon variability during the late deglaciation and Holocene, Nat. Commun., 6, 1–7, https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms6916, 2015.

Lachniet, M. S., Denniston, R. F., Asmerom, Y., and Polyak, V. J.: Orbital control of western North America atmospheric circulation and climate over two glacial cycles, Nat. Commun., 5, 1–8, https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms4805, 2014.

Laskar, J., Robutel, P., Joutel, F., Gastineau, M., Correia, A.C.M., and Levrard, B.: A long term numerical solution for the insolation quantities of the Earth, Astron. Astr., 428, 261–285, https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361:20041335, 2004.

Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory: ESGF@DOE/LLNL, available at: https://esgf-node.llnl.gov/projects/esgf-llnl/, last access: 28 October 2020.

Lebamba, J., Vincens, A., and Maley, J.: Pollen, vegetation change and climate at Lake Barombi Mbo (Cameroon) during the last ca. 33 000 cal yr BP: a numerical approach, Clim. Past, 8, 59–78, https://doi.org/10.5194/cp-8-59-2012, 2012.

Lehner, B. and Grill G.: Global river hydrography and network routing: baseline data and new approaches to study the world's large river systems, Hydrol. Process., 27, 2171–2186, https://doi.org/10.1002/hyp.9740, 2013.

Lézine, A. M., Hély, C., Grenier, C., Braconnot, P., and Krinner, G.: Sahara and Sahel vulnerability to climate changes, lessons from Holocene hydrological data, Quaternary Sci. Rev., 30, 3001–3012, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2011.07.006, 2011.

Li, G., Zhang, H., Liu, X., Yang, H., Wang, X., Zhang, X., Jonell, T., Zhang, Y., Huang, X., Wang, Z., Wang, Y., Yu, L., and Xia, D.: Paleoclimatic changes and modulation of East Asian summer monsoon by high-latitude forcing over the last 130,000 years as revealed by independently dated loess-paleosol sequences on the NE Tibetan Plateau, Quaternary Sci. Rev., 237, 106283, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2020.106283, 2020.

Li, J., Dodson, J., Yan, H., Cheng, B., Zhang, X., Xu, Q., Ni, J., and Lu, F.: Quantitative precipitation estimates for the northeastern Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau over the last 18,000 years, J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos., 122, 5132–5143, https://doi.org/10.1002/2016jd026333, 2017.

Li, X., Liu, X., Qiu, L., An, Z., and Yin, Z. Y.: Transient simulation of orbital-scale precipitation variation in monsoonal East Asia and arid central Asia during the last 150 ka, J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos., 118, 7481–7488, https://doi.org/10.1002/jgrd.50611, 2013.

Li, Y. and Harrison, S. P.: Simulations of the impact of orbital forcing and ocean on the Asian summer monsoon during the Holocene, Global. Planet. Change., 60, 505–522, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloplacha.2007.06.002, 2008.

Li, Y. and Morrill, C.: Lake levels in Asia at the Last Glacial Maximum as indicators of hydrologic sensitivity to greenhouse gas concentrations, Quaternary Sci. Rev., 60, 1–12, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2012.10.045, 2013.

Li, Y., Wang, Y. G., Houghton, R. A., and Tang, L. S.: Hidden carbon sink beneath desert, Geophys. Res. Lett., 42, 5880–5887, https://doi.org/10.1002/2015gl064222, 2015.

Li, Y., Zhang, C., Wang, N., Han, Q., Zhang, X., Liu, Y., Xu, L., and Ye, W.: Substantial inorganic carbon sink in closed drainage basins globally, Nat. Geosci., 10, 501–506, https://doi.org/10.1038/ngeo2972, 2017.

Li, Y., Liu, Y., Ye, W., Xu, L., Zhu, G., Zhang, X., and Zhang, C.: A new assessment of modern climate change, China – An approach based on paleo-climate, Earth-Sci. Rev., 177, 458–477, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earscirev.2017.12.017, 2018.

Ljungqvist, F. C., Krusic, P. J., Sundqvist, H. S., Zorita, E., Brattstr, M, G., and Frank, D.: Northern hemisphere hydroclimate variability over the past twelve centuries, Nature, 532, 94–98, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature17418, 2016.

Lorenz, D. J., Nieto-Lugilde, D., Blois, J. L., Fitzpatrick, M. C., and Williams, J. W.: Downscaled and debiased climate simulations for North America from 21,000 years ago to 2100AD, Sci. Data., 3, 160048, https://doi.org/10.1038/sdata.2016.48, 2016.

Lowry, D. P. and Morrill, C.: Is the Last Glacial Maximum a reverse analog for future hydroclimate changes in the Americas?, Clim. Dynam., 52, 4407–4427, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00382-018-4385-y, 2019.

Magee, J. W., Miller, G. H., Spooner, N. A., and Questiaux, D.: Continuous 150 ky monsoon record from Lake Eyre, Australia: insolation-forcing implications and unexpected Holocene failure, Geology, 32, 885–888, https://doi.org/10.1130/g20672.1, 2004.

Mariotti, A.: How ENSO impacts precipitation in southwest central Asia, Geophys. Res. Lett., 34, L16706, https://doi.org/10.1029/2007gl030078, 2007.

Masutomi, Y., Inui, Y., Takahashi, K. and Matsuoka, Y.: Development of highly accurate global polygonal drainage basin data, Hydrol. Process., 23, 572–584, https://doi.org/10.1002/hyp.7186, 2009.

Metcalfe, S. E., Barron, J. A., and Davies, S. J.: The Holocene history of the North American Monsoon:`known knowns' and `known unknowns' in understanding its spatial and temporal complexity, Quaternary Sci. Rev., 120, 1–27, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2015.04.004, 2015.

Middleton, N. J. and Thomas, D. S. G. (Eds.): World Atlas of Desertification, Edward Arnold, London, The United Kingdom, 1997.

Miebach, A., Niestrath, P., Roeser, P., and Litt, T.: Impacts of climate and humans on the vegetation in northwestern Turkey: palynological insights from Lake Iznik since the Last Glacial, Clim. Past, 12, 575–593, https://doi.org/10.5194/cp-12-575-2016, 2016.

NOAA: Paleoclimatology Datasets, available at: https://www.ncdc.noaa.gov/data-access/paleoclimatology-data/datasets, last access: 28 October 2020.

Physical Sciences Laboratory: Climate Indices: Monthly Atmospheric and Ocean Time-Series, available at: https://psl.noaa.gov/data/climateindices/list/, last access: 28 October 2020.

Quade, J. and Broecker, W. S.: Dryland hydrology in a warmer world: Lessons from the Last Glacial period, Eur. Phys. J. Spec. Top., 176, 21–36, https://doi.org/10.1140/epjst/e2009-01146-y, 2009.

Rambeau, C. M. C.: Palaeoenvironmental reconstruction in the Southern Levant: synthesis, challenges, recent developments and perspectives, Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A., 368, 5225–5248, https://doi.org/10.1098/rsta.2010.0190, 2010.

Ramisch, A., Lockot, G., Haberzettl, T., Hartmann, K., Kuhn, G., Lehmkuhl, F., Schimpf, S., Schulte, P., Stauch, G., Wang, R., Wünnemann, B., Yan, D., Zhang, Y., and Diekmann, B.: A persistent northern boundary of Indian Summer Monsoon precipitation over Central Asia during the Holocene, Sci. Rep., 6, 1–7, https://doi.org/10.1038/srep25791, 2016.

Ran, M. and Feng, Z.: Holocene moisture variations across china and driving mechanisms: a synthesis of climatic records, Quaternary Int., 313–314, 179–193, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quaint.2013.09.034, 2013.

Rana, S., Mcgregor, J., and Renwick, J.: Wintertime precipitation climatology and ENSO sensitivity over central southwest Asia, Int. J. Climatol., 37, 1494–1509, https://doi.org/10.1002/joc.4793, 2017.

Rana, S., McGregor, J., and Renwick, J.: Dominant modes of winter precipitation variability over Central Southwest Asia and inter-decadal change in the ENSO teleconnection, Clim. Dynam., 53, 5689–5707, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00382-019-04889-9, 2019.

Roderick, M. L., Sun, F., Lim, W. H., and Farquhar, G. D.: A general framework for understanding the response of the water cycle to global warming over land and ocean, Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci., 18, 1575–1589, https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-18-1575-2014, 2014.

Routson, C. C., McKay, N. P., Kaufman, D. S., Erb, M. P., Goosse, H., Shuman, B. N., Rodysill, J. R., and Ault, T.: Mid-latitude net precipitation decreased with Arctic warming during the Holocene, Nature, 568, 83–87, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-019-1060-3, 2019.

Schmidt, G. A., Kelley, M., Nazarenko, L., Ruedy, R., Russell, G. L., Aleinov, I., Bauer, M., Bauer, S. E., Bhat, M. K., Bleck, R., Canuto, V., Chen, Y. H., Cheng, Y., Clune, T. L., Genio, A. D., de Fainchtein, R., Faluvegi, G., Hansen, J. E., Healy, R. J., Kiang, N. Y., Koch, D., Lacis, A. A., LeGrande, A. N., Lerner, J., Lo, K. K., Matthews, E. E., Menon, S., Miller, R. L., Oinas, V., Oloso, A. O., Perlwitz, J. P., Puma, M. J., Putman, W. M., Rind, D., Romanou, A., Sato, M., Shindell, D. T., Sun, S., Syed, R. A., Tausnev, N., Tsigaridis, K., Unger, N., Voulgarakis, A., Yao, M. S., and Zhang, J. L.: Configuration and assessment of the GISS ModelE2 contributions to the CMIP5 archive. J. Adv. Model. Earth Sy., 6, 141–184, https://doi.org/10.1002/2013ms000265, 2014.

Shakun, J. D. and Carlson, A. E.: A global perspective on Last Glacial Maximum to Holocene climate change, Quaternary Sci. Rev., 29, 1801–1816, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2010.03.016, 2010.

Shanahan, T. M., McKay, N. P., Hughen, K. A., Overpeck, J. T., Otto-Bliesner, B., Heil, C. W., King, J., Scholz, C. A., and Peck, J.: The time-transgressive termination of the African Humid Period, Nat. Geosci., 8, 140–144, https://doi.org/10.1038/ngeo2329, 2015.

Sime, L. C., Hodgson, D., Bracegirdle, T. J., Allen, C., Perren, B., Roberts, S., and de Boer, A. M.: Sea ice led to poleward-shifted winds at the Last Glacial Maximum: the influence of state dependency on CMIP5 and PMIP3 models, Clim. Past, 12, 2241–2253, https://doi.org/10.5194/cp-12-2241-2016, 2016.

Street-Perrott, F. A., Marchand, D. S., Roberts, N., and Harisson, S. P.: Global Lake-Level Variations from 18,000 to 0 Years Ago: A Paleoclimatic Analysis. U.S. Department of Energy Technical Report 46, Washington, D.C. 20545. Distributed by National Technical Information Service, Springfield, VA 22161, 1989.

Tabor, K. and Williams, J. W.: Globally downscaled climate projections for assessing the conservation impacts of climate change, Ecol. Appl., 20, 554–565, https://doi.org/10.1890/09-0173.1, 2010.

Taylor, K. E., Stouffer, R. J., and Meehl, G. A.: An overview of CMIP5 and the experiment design. B. Am. Meteorol. Soc., 93, 485–498, https://doi.org/10.1175/bams-d-11-00094.1, 2012.

Tierney, J. E., Smerdon, J. E., Anchukaitis, K. J., and Seager, R.: Multidecadal variability in east african hydroclimate controlled by the indian ocean, Nature, 493, 389–392, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature11785, 2013.

Trenberth, K. E., Dai, A., Schrier, G. V. D., Jones, P. D., Barichivich, J., Briffa, K. R., and Sheffield, J.: Global warming and changes in drought, Nat. Clim. Chang., 4, 17–22, https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate2067, 2013.

Voldoire, A., Sanchez-Gomez, E., Salas y Mélia, D., Decharme, B., Cassou, C., Sénési, S., Valcke, S., Beau, I., Alias, A., Chevallier, M., Déqué, M., Deshayes, J., Douville, H., Fernandez, E., Madec, G., Maisonnave, E., Moine, M.-P., Planton, S., Saint-Martin, D., Szopa, S., Tyteca, S., Alkama, R., Belamari, S., Braun, A., Coquart, L., and Chauvin, F.: The CNRM-CM5.1 global climate model: description and basic evaluation, Clim. Dynam., 40, 2091–2121, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00382-011-1259-y, 2013.

Wang, J., Song, C., Reager, J. T., Yao, F., Famiglietti, J. S., Sheng, Y., MacDonald, G. M., Brun, F., Schmied, H. M., Marston, R. A., and Wada, Y.: Recent global decline in endorheic basin water storages, Nat. Geosci., 11, 926–932, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41561-018-0265-7, 2018.

Wang, P. X., Wang, B., Cheng, H., Fasullo, J., Guo, Z. T., Kiefer, T., and Liu, Z. Y.: The global monsoon across timescales: coherent variability of regional monsoons, Clim. Past, 10, 2007–2052, https://doi.org/10.5194/cp-10-2007-2014, 2014.

Wang, P. X., Wang, B., Cheng, H., Fasullo, J., Guo, Z., Kiefer, T., and Liu, Z.: The global monsoon across time scales: Mechanisms and outstanding issues, Earth-Sci. Rev., 174, 84–121, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earscirev.2017.07.006, 2017.

Watanabe, S., Hajima, T., Sudo, K., Nagashima, T., Takemura, T., Okajima, H., Nozawa, T., Kawase, H., Abe, M., Yokohata, T., Ise, T., Sato, H., Kato, E., Takata, K., Emori, S., and Kawamiya, M.: MIROC-ESM 2010: model description and basic results of CMIP5-20c3m experiments, Geosci. Model Dev., 4, 845–872, https://doi.org/10.5194/gmd-4-845-2011, 2011.

Wurtsbaugh, W. A., Miller, C., Null, S. E., DeRose, R. J., Wilcock, P., Hahnenberger, M., Howe, F., and Moore, J.: Decline of the world's saline lakes, Nat. Geosci., 10, 816–821, https://doi.org/10.1038/ngeo3052, 2017.

WWF: HydroSHEDS, HydroBASINS Version 1.0, available at: https://www.hydrosheds.org/page/hydrobasins, last access: 28 October 2020.

Xue, B., Yu, G., and Zhang, F. J.: Late quaternary lake database in China, Science Press, Beijing, 2017 (in Chinese).

Yu, G., Harrison, S. P., and Xue, B.: Lake status records from China: data base documentation, MPI-BGC Tech Rep 4, 2001.

Yukimoto, S., Adachi, Y., Hosaka, M., Sakami, T., Yoshimura, H., Hirabara, M., Tanaka, T. Y., Shindo, E., Tsujino, H., and Deushi, M.: A new global climate model of the Meteorological Research Institute: MRI-CGCM3: Model description and basic performance, J. Meteorol. Soc. Jpn., 90, 23–64, https://doi.org/10.2151/jmsj.2012-a02, 2012.

Zhan, S., Song, C., Wang, J., Sheng, Y., and Quan, J.: A global assessment of terrestrial evapotranspiration increase due to surface water area change, Earth's future, 7, 266–282, https://doi.org/10.1029/2018ef001066, 2019.

Zhang, J., Chen, F., Holmes, J. A., Li, H., Guo, X., Wang, J., Li, S., Lü, Y., Zhao, Y., and Qiang, M.: Holocene monsoon climate documented by oxygen and carbon isotopes from lake sediments and peat bogs in China: a review and synthesis, Quaternary Sci. Rev., 30, 1973–1987, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2011.04.023, 2011.

Zhang, E,, Zhao, C., Xue, B., Liu, Z., Yu, Z., Chen, R., and Shen, J.: Millennial-scale hydroclimate variations in southwest China linked to tropical Indian Ocean since the Last Glacial Maximum, Geology, 45, 435–438, https://doi.org/10.1130/g38309.1, 2017.