the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

The elusive 8.2 ka event in speleothems from southern France

Maddalena Passelergue

Isabelle Couchoud

Russell N. Drysdale

John Hellstrom

Dirk L. Hoffmann

Alan Greig

The Holocene is generally considered a climatically stable period, yet a prominent perturbation occurred around 8.2 ka BP. Evidence of its impacts has been identified in many palaeoclimate archives across Europe. However, outside the Atlantic seaboard, no clear high-resolution signal for this event has emerged from southwestern Europe. Here, we investigate the potential impact of the 8.2 ka event in southern France through high-resolution multiproxy analyses of two speleothems from the Ardèche region. Variations in Mg Ca and Sr Ca of the speleothem calcite are mainly attributed to the prior calcite precipitation effect and indicate switches between drier and wetter conditions. The δ13C signal is likely influenced by soil development and biological activity, integrating both regional climate conditions and local geomorphology and hydrology. The pattern of speleothem δ18O changes do not correlate with regional palaeotemperature reconstructions and is therefore more likely related to hydrology, such as variations in the seasonality of karst recharge and/or the moisture source. During the 8.2 ka event, no distinct geochemical anomaly is recorded by the Ardèche speleothems, suggesting either a limited climatic impact in southern France or a lack of sensitivity of these speleothem proxies to respond to an event of this magnitude. While the muted δ18O response may be explained by its insensitivity to temperature changes and buffering by Mediterranean influences at the time, the absence of a clear hydrological response in Mg Ca, Sr Ca and δ13C remains unresolved. Therefore, despite a likely southward displacement of the mid-latitude westerlies induced by the 8.2 ka event, the Ardèche region may have remained under their influence, preventing a marked shift towards drier conditions. Consistent with other records from southern France, the lack of significant changes in our results that time challenges the spatial extent and uniformity of the impacts of the 8.2 ka event across western Europe.

- Article

(17142 KB) - Full-text XML

- BibTeX

- EndNote

The transition between the last glacial period and the Holocene is marked by significant climate and environmental changes, including increasing temperatures and greenhouse gases, ice-sheet melting and sea-level rise, and alteration of atmospheric and ocean circulation patterns (Bradley, 2005; Shi et al., 2020; Smith et al., 2011). Although the Holocene is characterised by a more stable regime, a series of major climate anomalies occurred (Bradley, 2005; Shi et al., 2020; Smith et al., 2011), the most prominent of which is the ∼ 8.2 ka event (where ka is thousands of year before 1950 CE, as with all dates mentioned hereafter) (Alley et al., 1997; Rohling and Pälike, 2005; Thomas et al., 2007). A widely accepted trigger for the 8.2 ka event is a substantial release of freshwater from proglacial Lake Agassiz-Ojibway into the Hudson Bay during the late stages of the Laurentide ice-sheet retreat (Barber et al., 1999). This massive freshwater discharge is believed to have altered the density and temperature of the ocean surface of the North Atlantic. The consequent slowing of the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC) and displacement of the deep-water convection zone (Barber et al., 1999; Ellison et al., 2006; Shi et al., 2020) resulted in a decrease in poleward heat transport and a cooling of Greenland surface air temperatures. This cooling, as well as the freshening of the ocean surface water recorded by lower δ18O and δ15N values in Greenland ice-cores, ultimately constrain the timing and duration of the 8.2 ka event to between 8.25 ± 0.05 and 8.09 ± 0.05 ka (Kobashi et al., 2007; North Greenland Ice Core Project members, 2004; Thomas et al., 2007). Due to its brief duration (∼ 160 years; Thomas et al., 2007), studying the impacts of the 8.2 ka event requires well-dated, high-resolution palaeoenvironmental records.

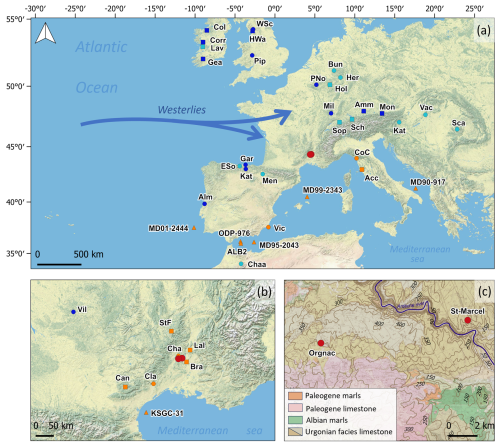

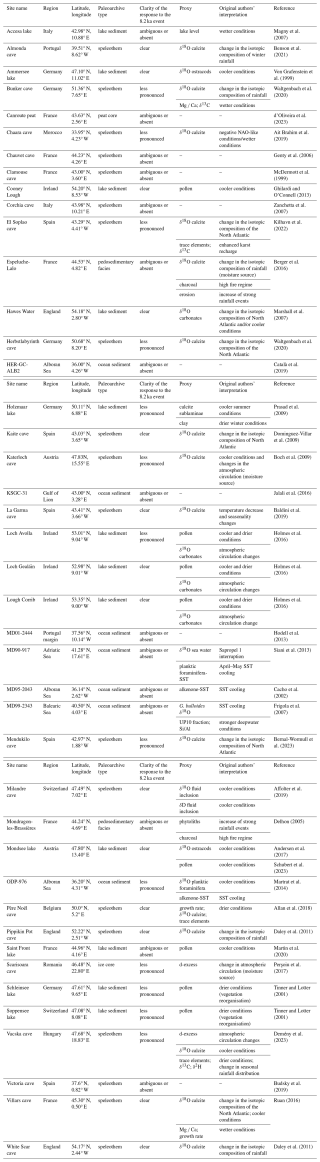

Figure 1(a) Location of Aven d'Orgnac and St-Marcel Cave (red dots; this study) and other European sites mentioned in the text (basemap: ESRI | Powered by Esri). (b) Regional location of the two caves in this study (red dots) and other southern France paleo-records cited in the text (basemap: ESRI | Powered by Esri). (c) Geological and topographical settings (modified after the Bureau de Recherches Géologiques et Minières) of the study sites (red dots). Dots represent cave records, squares represent terrestrial sediments records and triangles represent marine sediment records. Colours indicates clarity level of paleoclimate proxy response to the 8.2 event (blue: clear signal; light blue: less pronounced signal; orange: ambiguous or absent signal). Details on the paleoproxy type and their interpretation are given Table A1. Acc: Accesa lake (Magny et al., 2007); ALB-2: Alboran Sea – core HER-GC-ALB2 (Català et al., 2019). Alm: Almonda cave (Benson et al., 2021); Amm: Ammersee lake (Von Grafenstein et al., 1999); Bra: Mondragon-Les Brassières (Delhon, 2005); Bun: Bunker Cave (Waltgenbach et al., 2020); Can: Canroute peat (d'Oliveira et al., 2023); Cha: Chauvet Cave (Genty et al., 2006); Chaa: Chaara Cave (Ait Brahim et al., 2019); Cla: Clamouse Cave (McDermott et al., 1999); CoC: Corchia Cave (Zanchetta et al., 2007) CoL: Cooney Lough (Ghilardi and O'Connell, 2013); Corr: Lough Corrib (Holmes et al., 2016); ESo: El Soplao Cave (Kilhavn et al., 2022); Gar: La Garma Cave (Baldini et al., 2019); Gea: Loch Gealain (Holmes et al., 2016); Her: Herbstlabyrinth Cave (Waltgenbach et al., 2020); Hol: Holzmaar lake (Prasad et al., 2009); HWa: Hawes Water (Marshall et al., 2007); Kai: Kaite Cave (Dominguez-Villar et al., 2009); Kat: Katerloch Cave (Boch et al., 2009); KSGC-31: Gulf of Lion (Jalali et al., 2016); Lal: Espeluche-Lalo archeological site (Berger et al., 2016); Lav: Loch Avolla (Holmes et al., 2016); MD01-2444: Portuguese margin (Hodell et al., 2013); MD90-917: Adriatic Sea (Siani et al., 2013); MD95-2043: Alboran Sea (Cacho et al., 2002); MD99-2343: Balearic Sea (Frigola et al., 2007); Men: Mendukilo Cave (Bernal-Wormull et al. 2023); Mil: Milandre Cave (Affolter et al., 2019); Mon: Mondsee lake (Andersen et al., 2017; Schubert et al., 2023); ODP-976: Alboran Sea (Martrat et al., 2014) Pip: Pippikin Cave (Daley et al., 2011); PNo: Père Noël cave (Allan et al., 2018); Sca: Scarisoara Cave (Perşoiu et al., 2017); Sch: Schleinsee lake (Tinner and Lotter, 2001); Sop: Soppensee lake (Tinner and Lotter, 2001); StF: Saint Front lake (Martin et al., 2020); Vac: Vacska Cave (Demény et al., 2023); Vil: Villars Cave (Genty et al., 2006); Vic: Victoria Cave (Budsky et al., 2019); WSc: White Scar Cave (Daley et al., 2011).

Europe is strongly impacted by conditions in the North Atlantic, particularly via the influence of the westerlies. Thus, the 8.2 ka event is clearly recorded on the Atlantic seaboard as a decrease in the δ18O of stalagmites from the Iberian Peninsula (Baldini et al., 2019; Benson et al., 2021; Dominguez-Villar et al., 2009; Kilhavn et al., 2022) to as far north as the British Isles (Daley et al., 2011). Although less pronounced, similar signals are evident in stalagmite proxies (e.g. Allan et al., 2018; Demény et al., 2023; Waltgenbach et al., 2020; Fig. 1a) and ice cores (e.g. Perşoiu et al., 2017) located north and east of the Alps. Other palaeoenvironmental archives (Ghilardi and O'Connell, 2013; Von Grafenstein et al., 1999; Holmes et al., 2016; Marshall et al., 2007; Prasad et al., 2009; Schubert et al., 2023; Tinner and Lotter, 2001) also record the influence of the 8.2 ka event in northern and continental Europe. In contrast, in the north-western Mediterranean area, evidence for clear climatic changes linked to the 8.2 ka event is more ambiguous (Fig. 1a, b). In the western Mediterranean Sea, a possible link between a period of intensification of westerly winds around 9–7 ka and the 8.2 ka event has been inferred (Cacho et al., 2002; Frigola et al., 2007). However, inconsistency in the duration of the two events, as well as inadequate chronological constraints, make such a connection unclear. Similarly, a cooling between 9.0 and 8.2 ka has been recorded in the alkenone-derived SST record of MD95-2043 (Alboran Sea; Cacho et al., 2002), but this is not supported by the G. bulloides-Mg Ca derived SST record from the same core (Català et al., 2019), nor by SST records of other sediment cores from Gulf of Lion, Alboran Sea and Balearic Sea (Català et al., 2019; Jalali et al., 2016). Some records suggest that the climatic effects associated with deposition of sapropel S1, a time interval within which the 8.2 ka event occurred, masks the possible influence of the latter in Italy and the Adriatic Sea (e.g. Magny et al., 2007; Siani et al., 2013; Zanchetta et al., 2007). However, at a similar latitude, but outside the region affected by sapropel-related climate changes, the Atlantic core MD01-2444 (Iberian margin) shows no clear evidence of the 8.2 ka event (Hodell et al., 2013). More generally, there are no high-resolution records in the western Mediterranean region showing significant changes that can be attributed unequivocally to the 8.2 ka event (e.g. Budsky et al., 2019; Català et al., 2019; d'Oliveira et al., 2023; Jalali et al., 2016; Fig. 1a, b).

Despite its proximity to the Atlantic Ocean and the dominance of the mid-latitude westerlies, few high-resolution data are available for this period from France. Of these, only the δ18O from a Villars Cave speleothem appears to have recorded variations that could be related to the 8.2 ka event (Jiaoyang Ruan, unpublished thesis, 2016; Fig. 1b). Further south, in the Rhône Valley, evidence from anthracological, geomorphological and phytolith data from Lalo and Les Brassières sites suggests the occurrence of more frequent, short and intense rainfall during the 8.2–8.1 ka period, synchronous with a high fire regime. These conditions, occurring during a period marked by an overall dry climate, led to soil degradation and erosion, and may be linked to the hydrological impact of the 8.2 ka event (Berger et al., 2016; Delhon, 2005). However, anthracological assemblages from both Lalo and Les Brassières do not support perturbations of sufficient intensity to alter vegetation dynamics at 8.2 ka (Delhon, 2005). The speleothem isotopic records from Chauvet (Genty et al., 2006) and Clamouse (McDermott et al., 1999) Caves do not show any clear response to the 8.2 ka event. Similarly, high-resolution molecular biomarkers (brGDGTs), pollen (Canroute peat bog; d'Oliveira et al., 2023), TERR-alkanes and alkenone-SSTs records (Gulf of Lion; Jalali et al., 2016) from Southern France sediment cores do not indicate any significant changes that could be associated with the event. Therefore, the nature of the impacts of the 8.2 ka event in France, and more broadly in southern Europe, needs further substantiation.

This study aims to contribute to the pool of data for this region by presenting new well-dated, high-resolution stalagmite records from southeastern France. We applied a multiproxy approach on two stalagmites collected from neighbouring caves in Ardèche, with a particular focus on the period 11.5 to 5.5 ka, in order to contextualise the 8.2 ka event and investigate the potential climatic impact of the event in southeastern France.

2.1 Study sites

The studied stalagmite samples come from two caves located on the Ardèche limestone plateau, approximately 15 km west of the Rhône Valley (Fig. 1). The Upper Cretaceous limestone (Urgonian facies, very pure and massive reef limestone) plateau is incised by the Ardèche River, creating a gorge that meanders down to Pont Saint-Esprit. The surface of the plateau displays extensive karren and other dissolution features, and is characterised by thin soil or bare karst, with pockets of soil trapped in the surface dissolution features. A typical Mediterranean garrigue vegetation (low, thermophilic, and dominated by Quercus ilex) is present on the plateau. Saint-Marcel Cave is a several-km-long network located in the Ardèche gorge (natural entrance: 44°19′37′′ N, 4°32′20′′ E; Fig. 1c), extending under a watershed lying between ∼ 280 and 80 m a.s.l. The Aven d'Orgnac, situated 10 km further west, has a natural sinkhole entrance open on the plateau at 312 m a.s.l (44°19′11′′ N, 4°24′43′′ E; Fig. 1c). The proximity to the Mediterranean Sea (about 100 km to the south) results in a mixed meteorological influence, with rain-bearing air masses coming from both the Atlantic and the Mediterranean (Celle-Jeanton et al., 2001). More specifically, a 2-year daily precipitation study at Avignon (∼ 50 km south of Orgnac and St-Marcel caves) indicates that, despite a similar proportion of rain events from the Atlantic, the Mediterranean or of mixed origin (i.e. mid-latitude Atlantic Ocean, Western Mediterranean and Iberian peninsula origin), 52 % of the total precipitation is of Mediterranean origin, 12 % from the North Atlantic and the rest of mixed origin (Celle-Jeanton et al., 2001). In Ardèche, the meteorological station located at Orgnac (Genty et al., 2014) highlights a climate characterised by hot, dry summers followed by a significant increase in Mediterranean-origin precipitation in autumn (the so-called “Cevenol episodes”), which contributes notably to the karst recharge. The annual mean air temperature at Orgnac is 14.1 ± 0.5 °C, while the annual precipitation averages 934 ± 328 mm (data collected between 2001 and 2011; Genty et al., 2014).

Drip water monitoring could not be implemented at the study sites because the collected speleothems were either inactive or broken, with original in situ positions impossible to determine. Instead, the 10-year-long monitoring carried out at Chauvet Cave, a few kilometres away, is informative (Genty et al., 2014). In this region, the annual distribution of rainfall is biased towards autumn and winter months, with temperatures significantly higher in summer. Under such typically Mediterranean conditions, karst recharge is expected to be seasonally biased towards autumn and winter rainfall. Nevertheless, modern monitoring has shown that, despite its smaller contribution to karst recharge, summer rainfall needs to be considered to fully explain the δ18O of drip water (Genty et al., 2014). The study also reveals significant inter-annual mixing of the infiltrating rainwater.

Given the proximity to Chauvet, and the similar environmental context (i.e. air temperature, vegetation, nature and structure of the host rock), we can expect a similar composition of the recharge water at our sites. This does not, however, eliminate the potential influence of local soil and host rock variations (e.g. transmissivity, thickness of overburden) on the mixing time of infiltration water.

2.2 Speleothem samples

SM1-A is a fragment of a larger broken stalagmite collected on the floor of a large gallery within Network 1 of Saint-Marcel Cave (site called the “Gothic chapel”; ∼ 1400 m from the natural entrance; 120 m deep below the surface) in 2016. This stalagmite, whose base is missing, grew episodically since at least 123 ka. Only the upper 24 cm, formed during the Holocene, were investigated for this study. The growth period of this segment spans 11.3 to 0.2 ka. Its growth axis displays very subtle lateral shifts (of a few millimetres) and displays several faint discontinuities, potentially associated with brief growth hiatuses. The Holocene section is characterised by compact, translucent calcite while the faintly discernible lamination appears mostly in the milkier sections (i.e. enhanced micro-porosity), often limited to the axial zone (Fig. A1).

Stalagmite OR09-A was collected in 2009 from the Aven d'Orgnac, in the chamber “Salle 1” of the network section called “Orgnac II” (∼ 200 m from the natural entrance, a large sinkhole that likely opened during the Pleistocene; ∼ 110 m deep below the surface). It was standing in situ as a single piece at the time of collection and grew on a mud embankment. It exhibits a growth period between 11.1 and 0.5 ka without any visible hiatus over its 44 cm length (Fig. A2). This stalagmite grew very regularly and straight. It is similarly composed of calcite with a compact columnar fabric, with more variations in hue associated with either microporosity (milkier vs. more translucent sections) or the incorporation of red clay deposited during episodes of submersion by rising groundwaters when the Ardeche River was in flood. Detrital clay layers are more frequent at the base of the stalagmite and gradually diminish through the first third of the stalagmite until they totally disappear. They are not associated with identifiable deposition hiatuses.

2.3 U-Th dating

Age models were constructed from 17 uranium-thorium (U-Th) dates for SM1-A and 23 dates for OR09-A (Tables 1 and 2; Fig. 2). Samples were extracted using a dental air drill, yielding prisms of calcite each weighing approximately 200 mg. With the exception of eight OR09-A dating samples that were chemically prepared following the method detailed in Hoffmann et al. (2016), all other OR09-A and SM1-A dating samples were prepared following the method of Hellstrom (2003). The U and Th isotopic ratios were measured using a Thermo Finnigan Neptune MC-ICP-MS at the National Centre for Research on Human Evolution (CENIEH) in Burgos (Spain) following methods outlined in Hoffmann et al. (2007), and Nu Instruments Plasma MC-ICP-MS at the University of Melbourne (Australia) following methods outlined in Hellstrom (2003, 2006). An empirically derived initial thorium (230Th 232Thinitial) correction was applied to the ages, as described by Corrick et al. (2020), to reduce analytical error due to the presence of detrital thorium. An age-depth model for each stalagmite was built from these dates using the Finite Positive Growth Rate algorithm described by Corrick et al. (2020).

Table 1Uranium series analysis on stalagmite SM1-A determined by Hellstrom (2006) procedure. The analytical errors are provided with a 95 % uncertainty. Age in ka before 1950 AD corrected for initial 230Th using Eq. (1) of Hellstrom (2006), the decay constants of Cheng et al. (2013) and [230Th 232Th]i of 0.48 ± 0.32.

Table 2Uranium series analysis on stalagmite OR09-A determined by Hellstrom (2006; dates marked with an asterisk) or Hoffmann et al. (2007, 2016) procedure. The analytical errors are provided with a 95 % uncertainty. Age in ka before 1950 AD corrected for initial 230Th using Eq. (1) of Hellstrom (2006), the decay constants of Cheng et al. (2013) and [230Th 232Th]i of 0.48 ± 0.24.

Figure 2Age-depth models of (a) SM1-A (St-Marcel Cave, France) and (b) OR09-A (Aven d'Orgnac, France), calculated following the method described in Corrick et al. (2020). Dark and light red shaded areas correspond to 66 % and 95 % uncertainty envelopes. Depth is relative to the top of the stalagmite, and age is expressed in ka BP (1950).

2.4 Stable isotopes of carbon and oxygen

To obtain the variation over time of δ18O and δ13C, calcite samples were taken along the growth axis of the stalagmites. The samples were collected in powder form (∼ 1 mg) using a CNC Micromilling lathe equipped with a 1 mm drill bit, and moving with a 1 mm step along the growth axis. The samples were analysed at the University of Melbourne on a continuous-flow IRMS (Analytical Precision AP2003) after digestion in 105 % orthophosphoric acid. Normalisation to the VPDB scale was carried out using two standards (NEW1 and NEW12), previously calibrated against the standard international reference materials, NBS18 and NBS19. The 1σ analytical uncertainty on the sample measurements is 0.05 ‰ for δ13C and 0.1 ‰ for δ18O.

2.5 Trace elements

The analysis of magnesium (Mg) and strontium (Sr) concentrations relative to calcium (Ca) was carried out for SM1-A and OR09-A on subsamples of the same calcite powders used for isotopic analyses (i.e. at 1 mm step), making them directly comparable. Approximately 0.3 to 0.5 mg of calcite was dissolved in 15 mL of 2.5 % twice-distilled HNO3. Measurements were obtained using an Agilent 7700x quadrupole ICP-MS at the University of Melbourne. A mixed solution of sample digests was used to determine appropriate concentrations for the calibration standards and this mixture was also analysed every 10 samples to correct for instrument drift. The ratio of trace elements relative to 43Ca are based on 10 replicates of 500 measurements for each sample. Standards were run as unknowns every 19 samples to estimate the reproducibility, which presents a Relative Standard Deviation (RSD) of 0.13 % and 0.40 % for Mg Ca and Sr Ca respectively.

3.1 Dating, age model, and growth rates

All ages from the two stalagmites are in stratigraphic order and expressed in ka BP (1950). The concentration of 238U ranges from 80 to 161 ng g−1 for SM1-A and from 42 to 126 ng g−1 for OR09-A. SM1-A consists mostly of relatively clean calcite (high 230Th 232U activity ratios; Table 1). In contrast, the 230Th 232U activity ratios for OR09-A are generally below 100, even below 10 in some cases, indicating significant detrital contamination (Table 2). An empirically derived (230Th 232Thinitial) correction of 0.48 ± 0.24 was applied for OR09-A, however obtaining a similarly derived (230Th 232Thinitial) correction for SM1-A was challenging due to its low detrital Th concentration. Since Orgnac and St-Marcel caves are located nearby and have developed in the same bedrock, we applied the (230Th 232Thinitial) correction of OR09-A to SM1-A (0.48), but with an increased uncertainty of ±0.32 (2 SE).

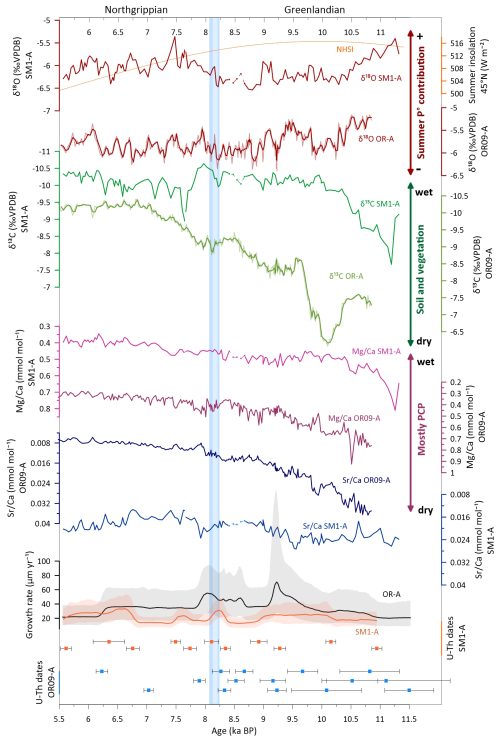

Figure 3Palaeoclimate proxy data from SM1-A (St-Marcel Cave, southern France) and OR09-A (Aven d'Orgnac, southern France) for the period targeted in this study (11.5 to 5.5 ka). From top to bottom: July insolation at 45° N (Laskar et al., 2004); δ18O of SM1-A and OR09-A; δ13C of SM1-A and OR09-A; Mg Ca and Sr Ca of SM1-A and OR09-A; growth rate of OR09-A and SM1-A; U-Th ages with their 2σ uncertainties for SM1-A and OR09-A. The shaded blue bar marks the 8.2 event period (Thomas et al., 2007), and the lightest part highlights the small variations questioned in SM1-A and OR09-A proxies. Dots and broken lines in SM1-A times series represent possible discontinuities not resolved by age-depth model. The δ18O and δ13C time-series of OR09-A have been smoothed (running average with a window of two values, thick lines) in order to display a similar temporal resolution to SM1-A time-series.

As Fig. 2 shows, the age-depth relationship for both stalagmites through the target interval of 11.5 to 5.5 ka is relatively constant, with SM1-A growth rates varying between 13 and 30 µm yr−1 and those for OR09-A, which grew ∼ twice faster, varying between 28 and 67 µm yr−1 (Fig. 3). The faint discontinuities observed in SM1-A, as noted above, cannot be resolved by the age-depth model. However, brief growth hiatuses cannot be excluded just before ∼ 8.4 ka and between ∼ 7.7 and 7.5 ka (Fig. A1).

3.2 Variations in stable isotopes and trace elements

The SM1-A δ18O varies from −6.5 to −5.4 ‰, while that of OR09-A varies from −6.4 to −5.2 ‰ during the period 11.5–5.5 ka. Generally, both δ18O signals follow similar trends: beyond secular variations, a decrease is observed during the Greenlandian, followed by stabilisation during the Northgrippian (Fig. 3). However, two periods of diverging δ18O patterns, at 9.7–9.3 and 8.0–7.6 ka, must be noted.

The δ13C values of both SM1-A and OR09-A show a decreasing trend during the Greenlandian; however, the major changes occur at different times (Fig. 3). Both records show, at first, a rapid increase of δ13C values, reaching a peak at ∼ 11.2 ka in SM1-A and ∼ 1100 years later in OR09-A. Then, the δ13C decreases sharply, until ∼ 9.9 ka in SM1-A, and ∼ 9.6 ka in OR09-A. Despite a peak at 7.6 ± 0.1 ka in SM1-A (Fig. 3), likely related to the growth discontinuity identified on the polished section (Fig. A1), the δ13C of SM1-A stabilises through the rest of the record, averaging around −10.2 ‰. In contrast, the δ13C of OR09-A first shows a gentle increase between ∼ 9.6 and ∼ 9.3 ka before a progressive decrease until ∼ 7.1 ka, after which it stabilises at around the same values as SM1 (Fig. 3).

The OR09-A Mg Ca ranges from 0.22 to 0.92 mmol mol−1, while Sr Ca values range between 0.003 and 0.037 mmol mol−1, except for one outlier (excluded from our results), presenting higher Mg and Sr concentration, likely due to laminae rich in detrital material. Both OR09-A trace elements show a general decreasing trend between 11.5 and 5.5 ka. Interestingly, several synchronous short-term and low-amplitude variations appear, seemingly in antiphase, the most prominent of which are centered on 10.5, 9.9 and 7.9 ka.

SM1-A magnesium concentration ranges from 0.35 to 0.81 mmol mol−1. Similar to OR09-A trace elements records, Mg Ca displays a decreasing trend over the period of interest. It notably shows a peak centred at ∼ 11.2 ka, synchronous with the δ13C peak in the same stalagmite (Fig. 3). In contrast, SM1-A Sr Ca shows a different behaviour: ranging from 0.013 to 0.027 mmol mol−1, it lacks a consistent long-term trend but rather contains several low-amplitude variations. The highest values are between ∼ 11.3 and ∼ 9.5 ka, after which they generally decrease until ∼ 6.7 ka, interrupted by a short interval of rising values between 8.3 to 7.9 ka, and before slightly increasing again until ∼ 5.5 ka (Fig. 3).

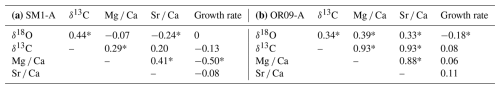

Table 3Spearman correlation coefficients (ρ) calculated among the different proxies of SM1-A (a) and of OR09-A (b). These tests were conducted on data from the period 11.5–5.5 ka BP, except for correlation tests involving the growth rate of SM1-A, which is only available for the period 10.9–5.5 ka BP. Asterisks indicate correlation coefficients that are statistically significant at the 5 % significance level (p < 0.05).

Spearman ρ correlation coefficients were calculated between each of the four SM1-A and OR09-A proxies and growth rate over the entire considered period (i.e. 11.5 to 5.5 ka) except for the SM1-A growth rate correlation coefficients, which cover the 10.9–5.5 ka period (i.e. the non-extrapolated limits of the age-depth model). The coefficients for SM1-A have values equal to or below , indicating weak to moderate correlation of the different proxies (Table 3a). In contrast, with the exception of the growth rate and δ18O, OR09-A proxies exhibit strong positive ρ values (> 0.88; Table 3b). To investigate the possibility of non-stationary covariance between speleothem proxies, running Spearman coefficients were calculated using windows of approximatively 1.2 ka, corresponding to 30 and 60 data points for SM1-A and OR09-A respectively (Fig. A3). The results differ widely between both stalagmites, with running ρ coefficients mostly showing weak to moderate correlations, punctuated by brief periods of strong and statistically significant correlation. However, such a time-specific approach in OR09-A and SM1-A reveals no additional information about proxy correlations.

In the time range corresponding to the 8.2 ka event defined by Thomas et al. (2007), i.e. between 8.25 ± 0.05 and 8.09 ± 0.05 ka, no significant changes can be identified in either the running correlation coefficients or the individual trace element time series. A slight increase of δ18O is present between ∼ 8.2 and ∼ 8.1 ka in both SM1-A and OR09-A, synchronous with a slight δ13C increase in OR09-A. However, these variations do not exceed the signal amplitude of the previous 1000-year period (9.3–8.3 ka; Fig. 3), and the other proxies show no significant excursions. Thus, the 8.2 ka event is not clearly identifiable in any proxy series of either of these speleothems.

4.1 Relevance of stable isotope ratios as palaeoclimatic proxies

The Hendy test (Hendy, 1971) had traditionally been used to evaluate whether speleothem calcite exhibits evidence of significant kinetic isotopic fractionation, which can interfere with the palaeoclimate information preserved in the δ13C and δ18O profiles. However, it has been demonstrated that the test criteria are not always reliable, and the accurate sampling required to apply the test is difficult to perform (Dorale and Liu, 2009). It has also been suggested that a “failed” Hendy test can be due to climate-driven changes in drip water chemistry that results in shifts speleothem isotopic values in the same direction (e.g. Hellstrom et al., 1998; Drysdale et al., 2006). Furthermore, there is evidence that the study of speleothems collected in cave chambers where strong kinetic fractionation is possible (due to, for example, rapid CO2 degassing and/or evaporation) may yield useful time series with large signal-to-noise ratios (Carlson et al., 2018), enhancing their palaeoclimatological value. Accordingly, owing to the mounting evidence that the Hendy test has fallen out of favour with the speleothem community, it was not performed on SM1-A and OR09-A.

Figure 4(a, c) SM1-A (St-Marcel Cave; light red and green lines with circles) and OR09-A (Aven d'Orgnac; dark red and green lines with triangles) δ18O and δ13C. The shaded envelopes are the modelled 95 % uncertainties derived from Monte Carlo simulations (10 000 iterations) that incorporate both age and stable isotope measurement errors. (b, d) Difference between both time series (Δδ18O and Δδ13C of OR09-A – SM1-A; grey solid lines) after interpolating the OR09-A series to the same age steps as SM1-A. The dashed grey lines (0 value) indicate the absence of difference between the δ18O or δ13C of both stalagmites. The shaded yellow area indicates the timing of the convergence of the δ18O and δ13C profiles of both stalagmites.

An arguably more convincing test for the lack of significant kinetic isotopic fractionation is how well the δ18O profiles of two or more coeval speleothems from the same cave or karst system compare. For most of the time interval, the δ18O signals of these stalagmites show similar trends with a limited amplitude (Fig. 4a). This is expected because δ18O is less susceptible than δ13C to the nuances of drip-water catchment heterogeneities (e.g. vegetation cover, soil thickness, karst plumbing). The offset in the δ18O profiles for the first part of the Holocene, when OR09-A shows generally higher values than SM1-A (Fig. 4a and b), may be due to local edaphic factors, where infiltration waters may have been subjected to higher evapotranspiration as they traversed the epikarst. The fact that the offset decreases with time until the two profiles converge at ∼ 7.7 ka (Fig. 4a and b) suggests that any effect of higher evapotranspiration diminished through time. This is consistent with the more pronounced offset between the two δ13C profiles across this same period, with the timing of the convergence of the two δ13C profiles almost identical to that for the δ18O profiles (Fig. 4c and d). Some brief divergence in δ18O also occurs during the periods 9.7–9.3 and 8.0–7.6 ka, but aside from this the two δ18O patterns are very similar.

In addition, the absence of consistent covariation between δ13C and δ18O in each of the stalagmites (Fig. 3) supports that calcite precipitation was not associated with significant kinetic fractionation. In summary, it is plausible that the progressive decrease in the offset in δ18O (and δ13C) between the two stalagmites (Fig. 4) is due to edaphic/vegetation-cover differences between their respective recharge zones catchments. For these reasons, we argue against significant in-cave kinetic fractionation and affirm the robustness of the records as potential palaeoclimate indicators (Couchoud, 2008; Lachniet, 2009).

4.2 Interpretation of proxies

4.2.1 Carbon isotopes

The δ13C of speleothem calcite can vary due to several, often competing, factors, including vegetation type, soil biogenic activity, and prior calcite precipitation (PCP), each of which is affected by the hydrological regime (McDermott, 2004). Considering that C3 vegetation taxa predominantly prevailed in the south of France during the Holocene (e.g. Berger et al., 2016; Martin et al., 2020), it is unlikely that the observed δ13C variations were significantly influenced by changes in vegetation type. Instead, a link between soil biogenic activity and the δ13C of Ardèche stalagmites seems more likely. The significant decrease in δ13C values at the beginning of the Holocene can be attributed to the resurgence of soil biogenic activity following post-glacial warming above the cave. As alluded to above, dissimilarities observed in the timing of the initial variations in OR09-A and SM1-A δ13C may reflect spatial differences in the Ardèche surface karst landscape, which is characterised by rugged terrain, steep slopes and abundant karstic dissolution features. These would give rise to intense spatial variations in soil thickness and development, and consequently variations in the evolution of vegetation cover and therefore potential biogenic CO2 supply. The δ13C is therefore likely primarily linked to the response of local environmental parameters to climate change, which would have evolved in a spatio-temporally heterogeneous manner across the plateau.

4.2.2 Trace elements

Magnesium and strontium concentrations in calcite can reflect hydrological variations in the vadose environment above the cave and/or variations in the proportion of host rock versus non-host rock (e.g. aerosol) contributions (Dredge et al., 2013; Regattieri et al., 2014; Verheyden et al., 2000). Excessive residence time of percolation water in the karst, which for a given flow path is directly related to water balance, is known to influence speleothem trace element concentrations (Regattieri et al., 2014; Verheyden et al., 2000). However, long residence times leave their mark most prominently in dolomitic terrains due to incongruent dissolution processes (Fairchild et al., 2000). The lack of dolomite in Ardeche makes it unlikely that this process strongly influences the trace element variations in SM1-A and OR09-A.

Figure 5Simple linear regression performed between ln(Sr Ca) and ln(Mg Ca) for SM1-A (a) and OR09-A (b) for the 11.5–5.5 ka period (equations and r2 values in blue) and the 11.0–6.5/9.6–6.1 ka periods (SM1-A and OR09-A respectively; equations and r2 values in red). Data removed for this second test are indicated by triangles.

Alternatively, PCP may explain the variations in Mg Ca and Sr Ca. The incidence of PCP can significantly affect percolation-water Mg Ca and Sr Ca during dry periods by reducing Ca concentrations along the flow path to the stalagmite, resulting in increased calcite Mg Ca and Sr Ca (McMillan et al., 2005; Regattieri et al., 2014; Verheyden et al., 2000). When trace element concentrations are linked to hydrological changes via PCP, strong positive covariation between Sr Ca and Mg Ca can be observed (e.g. Fairchild et al., 2000; McMillan et al., 2005; Regattieri et al., 2014). This can be further evaluated by applying the “Sinclair test” (Sinclair et al., 2012), where the slope of ln(Mg Ca) vs. ln(Sr Ca) should range between 0.71 and 1.45 (Wassenburg et al., 2020). In the Ardeche speleothems, the slope is lower than this range for SM1-A (0.5; Fig. 5a) but higher for OR09-A (1.6; Fig. 5b), suggesting the influence of processes other than PCP. Since such processes can potentially vary over time, we investigated piecewise variations in the slope of ln(Mg Ca) vs. ln(Sr Ca). In SM1-A, this reveals a slope of 0.88 for the period 11.0–6.5 ka, implying that PCP is likely the main driver of SM1-A Mg and Sr during this time interval (Fig. 5a). For the periods 11.5–11 and 6.5–5.5 ka, PCP may also have been occurring, but other processes had a significant influence. When applying the same approach to OR09-A, however, significant changes in the ln(Mg Ca) vs. ln(Sr Ca) slope are less obvious, which is reflected in the stronger overall correlation (Fig. 5b). This suggests that the processes modulating the Mg Ca and Sr Ca in the drip water feeding OR09-A remained relatively invariant throughout the 11.5–5.5 ka period (Fig. 5b). In spite of this, the ln(Mg Ca) vs. ln(Sr Ca) slope between 9.6 and 6.1 ka lies within the Sinclair range, with the slope being lower prior to 9.6 ka and higher after 6.1 ka.

A possible contribution from exotic sources of Mg and Sr, such as dust, may have occurred during periods where the ln(Mg Ca) vs. ln(Sr Ca) slope exceeds the 0.71–1.45 range. Loess deposits of Last Glacial age have been confirmed around the Ardeche region, and extend along the lower Rhone valley (Bosq et al., 2018). However, a full geochemical investigation is required to link these deposits as transient sources of trace elements in the Ardeche speleothems. This is beyond the scope of this paper.

It must be noted that growth rates can also influence Sr Ca values by altering the partitioning coefficient (Gabitov et al., 2014), but the correlation coefficient between the two variables for both stalagmites is very low (Table 3). Similar to results from natural-cave and cave-analogue laboratory studies (e.g. Huang and Fairchild, 2001; Tremaine and Froelich, 2013; Wassenburg et al., 2020), the absence of a clear relationship between Sr Ca and growth rate in SM1-A can be explained by a growth rate that is generally too low (i.e. less than 30 µm yr−1; Gabitov et al., 2014) and insufficiently variable to significantly impact Sr partitioning. Drip-water Sr and Mg concentration from monitoring would be useful to further investigate the relationship between growth rate and Sr Ca of Ardèche speleothem calcite (Huang and Fairchild, 2001).

In summary, the evidence suggests that for the period of interest, variations in Mg Ca and Sr Ca of SM1-A and OR09-A may mainly reflect PCP through changes in site moisture balance. This is particularly evident for the period surrounding the 8.2 ka event (i.e. between 9.6 and 6.1 ka). However, for the entirety of the 11.5–5.5 ka period, trace element variations cannot be fully explained by PCP alone, thus implying a significant impact of other factors, such as non-bedrock sources, on Mg and Sr incorporated in SM1-A and OR09-A.

4.2.3 Oxygen isotopes

The δ18O of speleothem calcite is primarily linked to the δ18O of local precipitation and the cave air temperature during drip-water-to-calcite isotopic fractionation. Numerous mechanisms perturb the rainfall δ18O signal between the moisture-source region and the cave (McDermott, 2004). At some sites, the calcite δ18O can be interpreted more or less as a direct proxy for air temperature (e.g. Fohlmeister et al., 2012; Parker and Harrison, 2022). This is typically the case in the high latitudes or at high altitudes because fractionation during air-mass rainout and condensation is accentuated as temperature falls (Dansgaard, 1964). However, in Ardèche, considering the local gradient between air temperature and precipitation δ18O of +0.18 ‰ °C−1 (Genty et al., 2014) and a drip-water-to-calcite fractionation of −0.18 ‰ °C−1 in the cave (Tremaine et al., 2011), there is currently approximately zero net effect of local air temperature on the calcite δ18O; this is probably the case for most, if not all of the Holocene. The lack of resemblance between the δ18O of our speleothems and some palaeotemperature reconstructions from southern France and the Gulf of Lion (e.g. d'Oliveira et al., 2023; Jalali et al., 2016; Martin et al., 2020) supports the idea that regional air-temperature change was not the main forcing parameter for the δ18O. Considering the general trend of SM1-A and OR09-A δ18O and the information provided by the other proxies, it is more likely that the δ18O variations were related to hydrological changes.

During the Greenlandian, warm temperatures (strong Northern Hemisphere summer insolation) and increased humidity (decreasing Mg Ca and Sr Ca) allowed for the development of soil and vegetation above the caves, leading to decreasing speleothem δ13C. Due to the summer water deficit and higher evapotranspiration rates characteristic of the Mediterranean climate, vegetation development may have significantly reduced the proportion of summer rainfall contributing to karst recharge. Thus, the combined effect of rainfall seasonality and vegetation cover development could have reduced the proportion of isotopically heavier summer rainfall contributing to the annually integrated δ18O of the karst recharge, which would explain the observed decrease in calcite δ18O during the Greenlandian. Finally, the Mediterranean influence is also noted by the fact that the absolute values of δ18O in our stalagmites are similar to other Mediterranean speleothems (Bernal-Wormull et al., 2023; Genty et al., 2014; McDermott et al., 1999), for which the input of Mediterranean-sourced precipitation has been invoked to explain higher values than those of other European archives situated beyond Mediterranean influence (Affolter et al., 2019; Fohlmeister et al., 2012; Waltgenbach et al., 2020).

4.3 The 8.2 ka event in southern France: a subtle event or an archival issue?

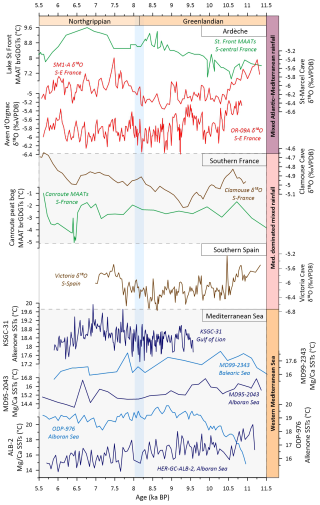

The high-resolution stable isotope and trace element time series of SM1-A and OR09-A display no significant change in Ardèche during the 8.2 ka event time frame. The lack of an unambiguous, prominent variation suggests a limited climatic impact of the 8.2 ka event in southern France. This would be consistent with the absence of clear responses recorded by other southern French stalagmites (Genty et al., 2006; McDermott et al., 1999; Fig. 6), pollen records (Jouffroy-Bapicot et al., 2007; Martin et al., 2020; d'Oliveira et al., 2023; Fig. 6), and marine sediment cores (Jalali et al., 2016; Fig. 6). Nevertheless, this conclusion seems to be at odds with palaeoenvironmental archives in other parts of western Europe (Fig. 7). Some of these records were interpreted in terms of a temperature decrease (e.g. Boch et al., 2009; Von Grafenstein et al., 1999; Tinner and Lotter, 2001). The low sensitivity of the investigated proxies of SM1-A and OR09-A to temperature changes, particularly as they were likely subtle (∼ −0.5 °C during the 8.2 ka event in the Mediterranean basin; Morrill et al., 2013; Wiersma and Renssen, 2006), would explain the absence of a clear temperature-driven 8.2 ka signal in Ardeche stalagmites.

Figure 6Selected palaeoclimate records cited in the text that show no clear evidence of changes associated with the 8.2 ka event. Green lines correspond to temperature values (MAAT) inferred from molecular biomarkers (brGDGTs) analysed from terrestrial lake and peat bog records; brown lines correspond to stable oxygen isotope values analysed from speleothem records; and blue lines correspond to sea-surface temperature (SST) values inferred from alkenones or Mg Ca ratios analysed from ocean-sediment records. Speleothem records from this study are shown in red. From top: Lake St. Front brGDGTs Mean Annual Air Temperature (MAAT; Martin et al., 2020); St-Marcel Cave calcite δ18O (SM1-A; this study); Aven d'Orgnac Cave calcite δ18O (OR09-A; this study); Clamouse Cave calcite δ18O (Cl-26; McDermott et al., 1999); Canroute peat bog brGDGTs MAAT (CAN02; d'Oliveira et al., 2023); Victoria Cave calcite δ18O (Vic-III-4; Budsky et al., 2019); Gulf of Lion SST (KSGC-31; Jalali et al., 2016); Balearic sea SST (MD99-2343; Català et al., 2019); and Alboran Sea SST (MD95-2043, ODP-976, HER-GC-ALB-2; Català et al., 2019; Martrat et al., 2014). All ocean-sediment core chronologies have been updated using the marine radiocarbon calibration curve Marine20 (Heaton et al., 2020), and age models calculated using the Bacon R package (Blaauw and Christen, 2011). The light-blue bar represents the time interval of the 8.2 ka event (after Thomas et al., 2007).

Figure 7Selection of European sites cited in the text that record the 8.2 ka event. The grey and black lines are the NGRIP stable oxygen isotope series (North Greenland Ice Core Project members, 2004) and the high-resolution Greenland ice-core composite (Thomas et al., 2007), respectively; the brown lines are stable oxygen isotope or temperature values (MAT) inferred from speleothems from White Scar Cave (WSC-97-10-5; Daley et al., 2011), Pippikin Pot Cave (YD01; Daley et al., 2011), Père Noël Cave (PN; Allan et al., 2018), Milandre Cave (Affolter et al., 2019), Katerloch Cave (K1; Boch et al., 2009), La Garma Cave (GAR-01; Baldini et al., 2019), Kaite Cave (LV5; Dominguez-Villar et al., 2009), and Mendukilo Cave (MEN2; Bernal-Wormull et al., 2023); and the green lines are ostracod stable oxygen isotope values from Lake Ammersee (A-S92-5; Von Grafenstein et al., 1999) and Lake Mondsee (MO_05; Andersen et al., 2017). Speleothem records from this study (Aven d'Orgnac and St-Marcel Caves) are shown in red. The light-blue vertical bar represents the time interval of the 8.2 ka event (after Thomas et al., 2007).

Other studies (e.g. Bernal-Wormull et al., 2023; Kilhavn et al., 2022; Waltgenbach et al., 2020) have interpreted the δ18O decrease associated with the 8.2 ka event as a change in the isotopic composition of the vapour source (i.e. freshening of the Atlantic Ocean surface; Ellison et al., 2006), which is supported by models simulating precipitation δ18O anomalies during the event (Holmes et al., 2016; Tindall and Valdes, 2011). Such a δ18O change is not recorded in SM1-A and OR09-A, although Ardèche is relatively close to the Atlantic Ocean and falls under the influence of the mid-latitude westerlies. This is likely explained by a significant proportion (if not the majority) of Mediterranean-sourced precipitation reaching the region: this carries a higher δ18O signature and thus would buffer a reduced δ18O signal from Atlantic moisture at the time of the 8.2 ka event (Celle-Jeanton et al., 2001; Genty et al., 2014).

The 8.2 ka event in Europe has also been associated with a drier climate (e.g. Allan et al., 2018; Baldini et al., 2002), which is supported by a model-data comparison (Wiersma and Renssen, 2006) and interpreted as the result of a decrease in the strength of the westerlies and their southward displacement, typical of negative NAO-like conditions (e.g. Ait Brahim et al., 2019; Benson et al., 2021; Holmes et al., 2016). The lack of a significant change at 8.2 ka recorded by our speleothem proxies could thus also be explained by Ardèche being situated in a less sensitive position to a westerlies shift. Indeed, if a southward shift occurred during the 8.2 ka event, it is likely that southern France was still under the westerlies path, but at its northern limit (Wassenburg et al., 2016). Thus, being situated in the transition zone, Ardèche climate may not have experienced a significant change to a drier climate. This is consistent with the finding of Tindall and Valdes (2011), who showed that the 8.2 ka event effect on precipitation change seems to have been geographically variable, and needs to be considered as a local rather than a regional marker (Tindall and Valdes, 2011).

At the local scale, the Ardèche climate may have experienced an increase in the frequency of intense hydrological events, as supported by phytolytic observations at two sites near the caves (i.e. Lalo, ∼ 40 km and Les Brassières, ∼ 25 km away; Berger et al., 2016; Delhon, 2005). These events notably appear during a period of frequent fires and increased Mediterranean-sourced precipitation (Berger et al., 2016). This is consistent with the small positive variation between 8.2 and 8.1 ka observed in the δ18O of both SM1-A and OR09-A, which could reflect a period of intensified summer rainfall events sourced from the Mediterranean Sea (e.g. as the aforementioned “Cevenol” rainfall episodes). Although the Lalo and Les Brassières studies highlight that this was not sufficient to overturn the local vegetation, these events may have significantly increased soil leaching and erosion (Berger et al., 2016; Delhon, 2005), which could have triggered the small δ13C increase in OR09-A. However, these δ18O and δ13C oscillations are insignificant when viewed against the millennial periods either side, precluding a confident conclusion about these influences.

In contrast with the idea of a major climatic disruption, the results of this study support a more subtle impact of the 8.2 ka event in southeastern France, with minimal if any discernible variations in temperature and precipitation. This statement is not incompatible with the clear 8.2 ka signal recorded at some European sites (Fig. 7). Indeed, most records showing a distinct negative δ18O anomaly are located near the Atlantic margin (e.g. Almonda Cave, Kaite Cave, White Scar Cave, Hawes Water Lake; Benson et al., 2021; Daley et al., 2011; Dominguez-Villar et al., 2009; Marshall et al., 2007; Fig. 7), making them directly exposed to δ18O-depleted Atlantic-sourced precipitation. These sites have high sensitivity to changes in the δ18O composition of the Atlantic Ocean and may have recorded an isotopic event without any abrupt changes in regional climate. Similarly, sites recording a cooling at 8.2 ka are mostly located in or near the Alps, or in northern Europe (e.g. Milandre Cave, Mondsee Lake, Ammersee Lake, Lough Corrib Lake; Andersen et al., 2017; Affolter et al., 2019; Von Grafenstein et al., 1999; Holmes et al., 2016; Fig. 7). In those areas, higher latitude, altitude or proximity to the Alps could explain an amplified cooling, allowing the event to be clearly recorded.

Additionally, it should be noted that some records from continental Europe (e.g. Holzmaar Lake, Prasad et al., 2009: Scarisoara Cave, Perşoiu et al., 2017) support the possibility of a seasonally biased impact of the 8.2 ka event, with stronger changes occurring during summer. This may explain the inconsistency of responses to the 8.2 ka event among paleorecords from the same region, some of whose proxies may be incapable of detecting seasonal changes. However, in the Western Mediterranean basin, the lack of clear evidence for the 8.2 ka event in both summer-biased and winter-biased, and local and regional, paleorecords suggests that the climatic changes associated with the event were of insufficient intensity and/or duration to register a proxy response (Fig. 6).

Therefore, the spatial distribution and characteristics of the 8.2 ka signals across Europe suggest a reconsideration of the generalised climatic expression of the event in favour of an isotopic perturbation of the North Atlantic moisture source associated with subtle and possibly seasonally biased climatic variations, with clearer expressions confined to regions either within or close to high-altitude (Alpine) areas, and to higher-latitude (northwestern European) regions.

Our multiproxy analysis (δ18O, δ13C, Mg Ca, Sr Ca) of stalagmites from St-Marcel Cave and Aven d'Orgnac in southeastern France does not reveal a significant climatic anomaly that can be linked to the 8.2 ka event, in spite of the caves being situated in close proximity to the Atlantic Ocean and falling under the influence of the westerlies. A lack of sensitivity of the stalagmites to air temperature changes in this region may explain partly the absence of a clear response in the calcite δ18O. A significant Mediterranean influence may have also contributed to attenuating or masking the effects of any North Atlantic freshening on the δ18O signal, but it does not explain the absence of a hydrological response from the δ13C, Mg Ca and Sr Ca. Whilst it is well known that these ratios do not always yield meaningful hydrological information at all cave sites, the positive covariance of Mg Ca and δ13C over the whole 11–5.5 ka interval suggests SM1-A and OR09-A were sensitive to hydrological change during their growth history, at least over the long term. This finding underscores the importance of multiproxy analyses to deconvolve climatic information and reduce interpretation errors.

The lack of a convincing climate response to the 8.2 ka event from this study is consistent with proxy data from several other sites in southern France and from the broader western Mediterranean basin. However, the results of this study stand in contrast to records obtained from some other European sites, particularly those near the Atlantic margin and in Alpine massif regions, where the event is clearly marked. This questions the nature and distribution of the impacts of the 8.2 ka climatic event. Modelling coupled with data provided by a range of archive types could help reconcile regional discrepancies between proxy records, provided that biases introduced by different archives/proxies and site effects are considered. Acquiring new high-resolution and precisely dated data from regions with complex hydrological regimes, like southeastern France, would be a considerable asset for better understanding the impacts of this event.

Table A1Summary of paleorecords shown in Fig. 1. For records capturing the 8.2 ka event (as reported by the original authors), the proxies that recorded the event and their interpretation are provided.

Figure A1Polished section of SM-1 stalagmite (St-Marcel Cave, France). At left, the U-Th dating samples and their ages (±95 % uncertainties) are indicated (ka BP; colour switching better facilitates matching age and sample position). Red dashed lines correspond to possible discontinuities that are unresolved by the age depth model.

Figure A2Polished section of OR09-A stalagmite (Aven d'Orgnac, France). At right, the U-Th dating samples and their ages (±95 % uncertainties) are indicated (ka BP; colour switching better facilitates matching age and sample position).

Figure A3Spearman running coefficients of (a) SM1-A (window = 30 values) and (b) OR09-A (window = 60 values) δ18O and δ13C (yellow); δ18O and Mg Ca (green); δ18O and Sr Ca (purple); δ13C and Mg Ca (grey); δ13C and Sr Ca (pink) and Mg Ca and Sr Ca (blue). The grey shaded areas indicate values of Spearman ρ that are not statistically significant at p < 0.05 (critical Spearman ρ value = and for SM1-A and OR09-A respectively). Variables are considered as strongly correlated when their Spearman correlation coefficients are above (below) (red dashed lines).

Data will be made available upon request.

IC conceived the project, and prepared and sampled the speleothems for analyses. RD performed the stable isotope measurements. JH and DH made the U-Th measurements. AG carried out the trace element analyses. MP analysed and interpreted the data with guidance from IC and RD. MP prepared the manuscript and created figures. IC and RD supervised analysis of all proxy data and helped to write the manuscript. All authors edited the final version.

At least one of the (co-)authors is a member of the editorial board of Climate of the Past. The peer-review process was guided by an independent editor, and the authors also have no other competing interests to declare.

Publisher's note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims made in the text, published maps, institutional affiliations, or any other geographical representation in this paper. The authors bear the ultimate responsibility for providing appropriate place names. Views expressed in the text are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher.

We sincerely thank the entire teams at Aven d'Orgnac and St-Marcel Cave for their hospitality during our various field visits and for their interest in this work, especially Joël Ughetto, Stéphane Tocino, Françoise Prud'homme, and Delphine Dupuy. We are also grateful to colleagues and students who occasionally lent a helping hand in the field or provided some of their time by participating in sample preparation in the various laboratories: Didier Cailhol, Ellen Corrick, Stéphane Jaillet, Petra Bajo, Serene Paul, Timothy Pollard, Jérémie Gaillard, Maeva Monnier and Cloé Inzaina.

EDYTEM, UMR 5204 CNRS lab supported the master internship of MP.

This research has been supported by the French National program LEFE (Les Enveloppes Fluides et l'Environnement).

This paper was edited by Odile Peyron and reviewed by three anonymous referees.

Affolter, S., Häuselmann, A., Fleitmann, D., Edwards, R. L., Cheng, H., and Leuenberger, M.: Central Europe temperature constrained by speleothem fluid inclusion water isotopes over the past 14 000 years, Sci. Adv., 5, eaav3809, https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aav3809, 2019.

Ait Brahim, Y., Wassenburg, J. A., Sha, L., Cruz, F. W., Deininger, M., Sifeddine, A., Bouchaou, L., Spötl, C., Edwards, R. L., and Cheng, H.: North Atlantic Ice-Rafting, Ocean and Atmospheric Circulation During the Holocene: Insights From Western Mediterranean Speleothems, Geophysical Research Letters, 46, 7614–7623, https://doi.org/10.1029/2019GL082405, 2019.

Allan, M., Fagel, N., Van Der Lubbe, H. J. L., Vonhof, H. B., Cheng, H., Edwards, R. L., and Verheyden, S.: High-resolution reconstruction of 8.2-ka BP event documented in Père Noël cave, southern Belgium, J. Quaternary Science, 33, 840–852, https://doi.org/10.1002/jqs.3064, 2018.

Alley, R. B., Mayewski, P. A., Sowers, T., Stuiver, M., Taylor, K. C., and Clark, P. U.: Holocene climatic instability: A prominent, widespread event 8200 yr ago, Geol., 25, 483, https://doi.org/10.1130/0091-7613(1997)025<0483:HCIAPW>2.3.CO;2, 1997.

Andersen, N., Lauterbach, S., Erlenkeuser, H., Danielopol, D. L., Namiotko, T., Hüls, M., Belmecheri, S., Dulski, P., Nantke, C., Meyer, H., Chapligin, B., Von Grafenstein, U., and Brauer, A.: Evidence for higher-than-average air temperatures after the 8.2 ka event provided by a Central European δ18O record, Quaternary Science Reviews, 172, 96–108, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2017.08.001, 2017.

Baldini, J. U. L., McDermott, F., and Fairchild, I. J.: Structure of the 8200-year cold event revealed by a speleothem trace element record, Science, 296, 2203–2206, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1071776, 2002.

Baldini, L. M., Baldini, J. U. L., McDermott, F., Arias, P., Cueto, M., Fairchild, I. J., Hoffmann, D. L., Mattey, D. P., Müller, W., Nita, D. C., Ontañón, R., Garciá-Moncó, C., and Richards, D. A.: North Iberian temperature and rainfall seasonality over the Younger Dryas and Holocene, Quaternary Science Reviews, 226, 105998, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2019.105998, 2019.

Barber, D. C., Dyke, A., Hillaire-Marcel, C., Jennings, A. E., Andrews, J. T., Kerwin, M. W., Bilodeau, G., McNeely, R., Southon, J., Morehead, M. D., and Gagnon, J.-M.: Forcing of the cold event of 8200 years ago by catastrophic drainage of Laurentide lakes, Nature, 400, 344–348, https://doi.org/10.1038/22504, 1999.

Benson, A., Hoffmann, D. L., Daura, J., Sanz, M., Rodrigues, F., Souto, P., and Zilhão, J.: A speleothem record from Portugal reveals phases of increased winter precipitation in western Iberia during the Holocene, The Holocene, 31, 1339–1350, https://doi.org/10.1177/09596836211011666, 2021.

Berger, J.-F., Delhon, C., Magnin, F., Bonté, S., Peyric, D., Thiébault, S., Guilbert, R., and Beeching, A.: A fluvial record of the mid-Holocene rapid climatic changes in the middle Rhone valley (Espeluche-Lalo, France) and of their impact on Late Mesolithic and Early Neolithic societies, Quaternary Science Reviews, 136, 66–84, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2015.11.019, 2016.

Bernal-Wormull, J. L., Moreno, A., Bartolomé, M., Arriolabengoa, M., Pérez-Mejías, C., Iriarte, E., Osácar, C., Spötl, C., Stoll, H., Cacho, I., Edwards, R. L., and Cheng, H.: New insights into the climate of northern Iberia during the Younger Dryas and Holocene: The Mendukilo multi-speleothem record, Quaternary Science Reviews, 305, 108006, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2023.108006, 2023.

Blaauw, M. and Christen, J. A.: Flexible paleoclimate age-depth models using an autoregressive gamma process, Bayesian Analysis, 6, 457–474, https://doi.org/10.1214/11-BA618, 2011.

Boch, R., Spötl, C., and Kramers, J.: High-resolution isotope records of early Holocene rapid climate change from two coeval stalagmites of Katerloch Cave, Austria, Quaternary Science Reviews, 28, 2527–2538, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2009.05.015, 2009.

Bosq, M., Bertran, P., Degeai, J.-P., Kreutzer, S., Queffelec, A., Moine, O., and Morin, E.: Last Glacial aeolian landforms and deposits in the Rhône Valley (SE France): Spatial distribution and grain-size characterization, Geomorphology, 318, 250–269, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geomorph.2018.06.010, 2018.

Bradley, R.: Climate forcing during Holocene, in: Global Change in the Holocene, edited by: Mackay A., Battarbee R., Birks J., and Oldfield F., Routledge, London, UK, https://doi.org/10.22498/pages.11.2-3.18, 2005.

Budsky, A., Scholz, D., Wassenburg, J. A., Mertz-Kraus, R., Spötl, C., Riechelmann, D. F., Gibert, L., Jochum, K. P., and Andreae, M. O.: Speleothem δ13C record suggests enhanced spring/summer drought in south-eastern Spain between 9.7 and 7.8 ka – A circum-Western Mediterranean anomaly?, The Holocene, https://doi.org/10.1177/0959683619838021, 2019.

Cacho, I., Grimalt, J. O., and Canals, M.: Response of the Western Mediterranean Sea to rapid climatic variability during the last 50 000 years: a molecular biomarker approach, Journal of Marine Systems, 33–34, 253–272, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0924-7963(02)00061-1, 2002.

Carlson, P. E., Miller, N. R., Banner, J. L., Breecker, D. O., and Casteel, R. C.: The potential of near-entrance stalagmites as high-resolution terrestrial paleoclimate proxies: Application of isotope and trace-element geochemistry to seasonally-resolved chronology, Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 235, 55–75, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gca.2018.04.036, 2018.

Català, A., Cacho, I., Frigola, J., Pena, L. D., and Lirer, F.: Holocene hydrography evolution in the Alboran Sea: a multi-record and multi-proxy comparison, Clim. Past, 15, 927–942, https://doi.org/10.5194/cp-15-927-2019, 2019.

Celle-Jeanton, H., Travi, Y., and Blavoux, B.: Isotopic typology of the precipitation in the Western Mediterranean Region at three different time scales, Geophysical Research Letters, 28, 1215–1218, https://doi.org/10.1029/2000GL012407, 2001.

Cheng, H., Lawrence Edwards, R., Shen, C.-C., Polyak, V. J., Asmerom, Y., Woodhead, J., Hellstrom, J., Wang, Y., Kong, X., Spötl, C., Wang, X., and Calvin Alexander, E.: Improvements in 230Th dating, 230Th and 234U half-life values, and U–Th isotopic measurements by multi-collector inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry, Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 371–372, 82–91, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2013.04.006, 2013.

Corrick, E. C., Drysdale, R. N., Hellstrom, J. C., Capron, E., Rasmussen, S. O., Zhang, X., Fleitmann, D., Couchoud, I., and Wolff, E.: Synchronous timing of abrupt climate changes during the last glacial period, Science, 369, 963–969, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aay5538, 2020.

Couchoud, I.: Les isotopes stables de l'oxygène et du carbone dans les spéléothèmes: des archives paléoenvironnementales, Quaternaire, 275–291, https://doi.org/10.4000/quaternaire.4532, 2008.

Daley, T. J., Thomas, E. R., Holmes, J. A., Street-Perrott, F. A., Chapman, M. R., Tindall, J. C., Valdes, P. J., Loader, N. J., Marshall, J. D., Wolff, E. W., Hopley, P. J., Atkinson, T., Barber, K. E., Fisher, E. H., Robertson, I., Hughes, P. D. M., and Roberts, C. N.: The 8200 yr BP cold event in stable isotope records from the North Atlantic region, Global and Planetary Change, 79, 288–302, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloplacha.2011.03.006, 2011.

Dansgaard, W.: Stable isotopes in precipitation, Tellus, 16, 436–468, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2153-3490.1964.tb00181.x, 1964.

Delhon, C.: Anthropisation et paléoclimats du tardiglaciaire à l'Holocène en moyenne vallée du Rhône: études pluridisciplinaires des spectres phytolithiques et pédo-anthracologiques de séquences naturelles et de sites archéologiques, PhD thesis, University Paris 1, https://theses.fr/2005PA010511 (last access: 6 February 2026), 2005.

Demény, A., Czuppon, G., Kern, Z., Hatvani, I. G., Topál, D., Karlik, M., Surányi, G., Molnár, M., Kiss, G. I., Szabó, M., Shen, C.-C., Hu, H.-M., and May, Z.: A speleothem record of seasonality and moisture transport around the 8.2 ka event in Central Europe (Vacska Cave, Hungary), Quat. Res., 1–16, https://doi.org/10.1017/qua.2023.33, 2023.

d'Oliveira, L., Dugerdil, L., Ménot, G., Evin, A., Muller, S. D., Ansanay-Alex, S., Azuara, J., Bonnet, C., Bremond, L., Shah, M., and Peyron, O.: Reconstructing 15 000 years of southern France temperatures from coupled pollen and molecular (branched glycerol dialkyl glycerol tetraether) markers (Canroute, Massif Central), Clim. Past, 19, 2127–2156, https://doi.org/10.5194/cp-19-2127-2023, 2023.

Dominguez-Villar, D., Fairchild, I. J., Baker, A., Wang, X., Edwards, R. L., and Cheng, H.: Oxygen isotope precipitation anomaly in the North Atlantic region during the 8.2 ka event, Geology, 37, 1095–1098, https://doi.org/10.1130/G30393A.1, 2009.

Dorale, J. and Liu, Z.: Limitations of Hendy Test criteria in judging the paleoclimatic suitability of speleothems and the need for replication, Journal of Cave and Karst Studies, 71, 73–80, 2009.

Dredge, J., Fairchild, I. J., Harrison, R. M., Fernandez-Cortes, A., Sanchez-Moral, S., Jurado, V., Gunn, J., Smith, A., Spötl, C., Mattey, D., Wynn, P. M., and Grassineau, N.: Cave aerosols: distribution and contribution to speleothem geochemistry, Quaternary Science Reviews, 63, 23–41, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2012.11.016, 2013.

Drysdale, R., Zanchetta, G., Hellstrom, J., Maas, R., Fallick, A., Pickett, M., Cartwright, I., and Piccini, L.: Late Holocene drought responsible for the collapse of Old World civilizations is recorded in an Italian cave flowstone, Geology, 34, 101–104, https://doi.org/10.1130/G22103.1, 2006.

Ellison, C. R. W., Chapman, M. R., and Hall, I. R.: Surface and Deep Ocean Interactions During the Cold Climate Event 8200 Years Ago, Science, 312, 1929–1932, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1127213, 2006.

Fairchild, I. J., Borsato, A., Tooth, A. F., Frisia, S., Hawkesworth, C. J., Huang, Y., McDermott, F., and Spiro, B.: Controls on trace element (Sr–Mg) compositions of carbonate cave waters: implications for speleothem climatic records, Chemical Geology, 166, 255–269, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0009-2541(99)00216-8, 2000.

Fohlmeister, J., Schröder-Ritzrau, A., Scholz, D., Spötl, C., Riechelmann, D. F. C., Mudelsee, M., Wackerbarth, A., Gerdes, A., Riechelmann, S., Immenhauser, A., Richter, D. K., and Mangini, A.: Bunker Cave stalagmites: an archive for central European Holocene climate variability, Clim. Past, 8, 1751–1764, https://doi.org/10.5194/cp-8-1751-2012, 2012.

Frigola, J., Moreno, A., Cacho, I., Canals, M., Sierro, F. J., Flores, J. A., Grimalt, J. O., Hodell, D. A., and Curtis, J. H.: Holocene climate variability in the western Mediterranean region from a deepwater sediment record, Paleoceanography, 22, https://doi.org/10.1029/2006PA001307, 2007.

Gabitov, R. I., Sadekov, A., and Leinweber, A.: Crystal growth rate effect on Mg Ca and Sr Ca partitioning between calcite and fluid: An in situ approach, Chemical Geology, 367, 70–82, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemgeo.2013.12.019, 2014.

Genty, D., Blamart, D., Ghaleb, B., Plagnes, V., Causse, Ch., Bakalowicz, M., Zouari, K., Chkir, N., Hellstrom, J., and Wainer, K.: Timing and dynamics of the last deglaciation from European and North African δ13C stalagmite profiles – comparison with Chinese and South Hemisphere stalagmites, Quaternary Science Reviews, 25, 2118–2142, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2006.01.030, 2006.

Genty, D., Labuhn, I., Hoffmann, G., Danis, P. A., Mestre, O., Bourges, F., Wainer, K., Massault, M., Van Exter, S., Régnier, E., Orengo, Ph., Falourd, S., and Minster, B.: Rainfall and cave water isotopic relationships in two South-France sites, Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 131, 323–343, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gca.2014.01.043, 2014.

Ghilardi, B. and O'Connell, M.: Early Holocene vegetation and climate dynamics with particular reference to the 8.2 ka event: pollen and macrofossil evidence from a small lake in western Ireland, Veget. Hist. Archaeobot., 22, 99–114, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00334-012-0367-x, 2013.

Heaton, T. J., Köhler, P., Butzin, M., Bard, E., Reimer, R. W., Austin, W. E. N., Ramsey, C. B., Grootes, P. M., Hughen, K. A., Kromer, B., Reimer, P. J., Adkins, J., Burke, A., Cook, M. S., Olsen, J., and Skinner, L. C.: Marine20 – The Marine Radiocarbon Age Calibration Curve (0–55 000 cal BP), Radiocarbon, 62, 779–820, https://doi.org/10.1017/RDC.2020.68, 2020.

Hellstrom, J.: Rapid and accurate U/Th dating using parallel ion-counting multi-collector ICP-MS, J. Anal. At. Spectrom., 18, 1346, https://doi.org/10.1039/b308781f, 2003.

Hellstrom, J.: U–Th dating of speleothems with high initial 230Th using stratigraphical constraint, Quaternary Geochronology, 1, 289–295, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quageo.2007.01.004, 2006.

Hellstrom, J., McCulloch, M., and Stone, J.: A Detailed 31,000-Year Record of Climate and Vegetation Change, from the Isotope Geochemistry of Two New Zealand Speleothems, Quaternary Research, 50, 167–178, https://doi.org/10.1006/qres.1998.1991, 1998.

Hendy, C. H.: The isotopic geochemistry of speleothems – I. The calculation of the effects of different modes of formation on the isotopic composition of speleothems and their applicability as palaeoclimatic indicators, Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 35, 801–824, https://doi.org/10.1016/0016-7037(71)90127-X, 1971.

Hodell, D., Crowhurst, S., Skinner, L., Tzedakis, P. C., Margari, V., Channell, J. E. T., Kamenov, G., Maclachlan, S., and Rothwell, G.: Response of Iberian Margin sediments to orbital and suborbital forcing over the past 420 ka, Paleoceanography, 28, 185–199, https://doi.org/10.1002/palo.20017, 2013.

Hoffmann, D. L., Prytulak, J., Richards, D. A., Elliott, T., Coath, C. D., Smart, P. L., and Scholz, D.: Procedures for accurate U and Th isotope measurements by high precision MC-ICPMS, International Journal of Mass Spectrometry, 264, 97–109, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijms.2007.03.020, 2007.

Hoffmann, D. L., Pike, A. W. G., García-Diez, M., Pettitt, P. B., and Zilhão, J.: Methods for U-series dating of CaCO3 crusts associated with Palaeolithic cave art and application to Iberian sites, Quaternary Geochronology, 36, 104–119, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quageo.2016.07.004, 2016.

Holmes, J. A., Tindall, J., Roberts, N., Marshall, W., Marshall, J. D., Bingham, A., Feeser, I., O'Connell, M., Atkinson, T., Jourdan, A.-L., March, A., and Fisher, E. H.: Lake isotope records of the 8200-year cooling event in western Ireland: Comparison with model simulations, Quaternary Science Reviews, 131, 341–349, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2015.06.027, 2016.

Huang, Y. and Fairchild, I.: Partitioning of Sr2+ and Mg2+ into calcite in karst-analogue experimental solutions, Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 65, 47–62, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0016-7037(00)00513-5, 2001.

Jalali, B., Sicre, M.-A., Bassetti, M.-A., and Kallel, N.: Holocene climate variability in the North-Western Mediterranean Sea (Gulf of Lions), Clim. Past, 12, 91–101, https://doi.org/10.5194/cp-12-91-2016, 2016.

Jouffroy-Bapicot, I., Pulido, M., Baron, S., Galop, D., Monna, F., Lavoie, M., Ploquin, A., Petit, C., de Beaulieu, J.-L., and Richard, H.: Environmental impact of early palaeometallurgy: Pollen and geochemical analysis, Vegetation History and Archaeobotany, 16, 251–258, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00334-006-0039-9, 2007.

Kilhavn, H., Couchoud, I., Drysdale, R. N., Rossi, C., Hellstrom, J., Arnaud, F., and Wong, H.: The 8.2 ka event in northern Spain: timing, structure and climatic impact from a multi-proxy speleothem record, Clim. Past, 18, 2321–2344, https://doi.org/10.5194/cp-18-2321-2022, 2022.

Kobashi, T., Severinghaus, J. P., Brook, E. J., Barnola, J.-M., and Grachev, A. M.: Precise timing and characterization of abrupt climate change 8200 years ago from air trapped in polar ice, Quaternary Science Reviews, 26, 1212–1222, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2007.01.009, 2007.

Lachniet, M. S.: Climatic and environmental controls on speleothem oxygen-isotope values, Quaternary Science Reviews, 28, 412–432, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2008.10.021, 2009.

Laskar, J., Robutel, P., Joutel, F., Gastineau, M., Correia, A. C. M., and Levrard, B.: A long-term numerical solution for the insolation quantities of the Earth, Astronomy & Astrophysics, 428, 261–285, https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361:20041335, 2004.

Magny, M., de Beaulieu, J.-L., Drescher-Schneider, R., Vannière, B., Walter-Simonnet, A.-V., Miras, Y., Millet, L., Bossuet, G., Peyron, O., Brugiapaglia, E., and Leroux, A.: Holocene climate changes in the central Mediterranean as recorded by lake-level fluctuations at Lake Accesa (Tuscany, Italy), Quaternary Science Reviews, 26, 1736–1758, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2007.04.014, 2007.

Marshall, J. D., Lang, B., Crowley, S. F., Weedon, G. P., Van Calsteren, P., Fisher, E. H., Holme, R., Holmes, J. A., Jones, R. T., Bedford, A., Brooks, S. J., Bloemendal, J., Kiriakoulakis, K., and Ball, J. D.: Terrestrial impact of abrupt changes in the North Atlantic thermohaline circulation: Early Holocene, UK, Geol., 35, 639, https://doi.org/10.1130/G23498A.1, 2007.

Martin, C., Ménot, G., Thouveny, N., Peyron, O., Andrieu-Ponel, V., Montade, V., Davtian, N., Reille, M., and Bard, E.: Early Holocene Thermal Maximum recorded by branched tetraethers and pollen in Western Europe (Massif Central, France), Quaternary Science Reviews, 228, 106109, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2019.106109, 2020.

Martrat, B., Jimenez-Amat, P., Zahn, R., and Grimalt, J. O.: Similarities and dissimilarities between the last two deglaciations and interglaciations in the North Atlantic region, Quaternary Science Reviews, 99, 122–134, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2014.06.016, 2014.

McDermott, F.: Palaeo-climate reconstruction from stable isotope variations in speleothems: a review, Quaternary Science Reviews, 23, 901–918, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2003.06.021, 2004.

McDermott, F., Frisia, S., Huang, Y., Longinelli, A., Spiro, B., Heaton, T. H. E., Hawkesworth, C. J., Borsato, A., Keppens, E., and Fairchild, I. J.: Holocene climate variability in Europe: Evidence from O, textural and extension-rate variations in three speleothems, Quaternary Science Reviews, 18, 1021–1038, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0277-3791(98)00107-3, 1999.

McMillan, E. A., Fairchild, I. J., Frisia, S., Borsato, A., and McDermott, F.: Annual trace element cycles in calcite-aragonite speleothems: evidence of drought in the western Mediterranean 1200–1100 yr BP, J. Quaternary Sci., 20, 423–433, https://doi.org/10.1002/jqs.943, 2005.

Morrill, C., Anderson, D. M., Bauer, B. A., Buckner, R., Gille, E. P., Gross, W. S., Hartman, M., and Shah, A.: Proxy benchmarks for intercomparison of 8.2 ka simulations, Clim. Past, 9, 423–432, https://doi.org/10.5194/cp-9-423-2013, 2013.

North Greenland Ice Core Project members: High-resolution record of Northern Hemisphere climate extending into the last interglacial period, Nature, 431, 147–151, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature02805, 2004.

Parker, S. E. and Harrison, S. P.: The timing, duration and magnitude of the 8.2 ka event in global speleothem records, Sci. Rep., 12, 10542, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-14684-y, 2022.

Perşoiu, A., Onac, B. P., Wynn, J. G., Blaauw, M., Ionita, M., and Hansson, M.: Holocene winter climate variability in Central and Eastern Europe, Sci. Rep., 7, 1196, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-01397-w, 2017.

Prasad, S., Witt, A., Kienel, U., Dulski, P., Bauer, E., and Yancheva, G.: The 8.2 ka event: Evidence for seasonal differences and the rate of climate change in western Europe, Global and Planetary Change, 67, 218–226, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloplacha.2009.03.011, 2009.

Regattieri, E., Zanchetta, G., Drysdale, R. N., Isola, I., Hellstrom, J. C., and Dallai, L.: Lateglacial to Holocene trace element record (Ba, Mg, Sr) from Corchia Cave (Apuan Alps, central Italy): paleoenvironmental implications: Trace element record from Corchia Cave, central Italy, J. Quaternary Sci., 29, 381–392, https://doi.org/10.1002/jqs.2712, 2014.

Rohling, E. J. and Pälike, H.: Centennial-scale climate cooling with a sudden cold event around 8200 years ago, Nature, 434, 975–979, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature03421, 2005.

Ruan, J.: Characterization of Holocene climate variability in the west of Europe and Mediterranean basin using high-resolution stalagmite records, PhD thesis, University Paris-Saclay (ComUE), https://theses.fr/2016SACLS223 (last access: 6 February 2026), 2016.

Schubert, A., Lauterbach, S., Leipe, C., Brauer, A., and Tarasov, P. E.: Visible or not? Reflection of the 8.2 ka BP event and the Greenlandian–Northgrippian boundary in a new high-resolution pollen record from the varved sediments of Lake Mondsee, Austria, Quaternary Science Reviews, 308, 108073, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2023.108073, 2023.

Shi, X., Lohmann, G., Sidorenko, D., and Yang, H.: Early-Holocene simulations using different forcings and resolutions in AWI-ESM, The Holocene, 30, 996–1015, https://doi.org/10.1177/0959683620908634, 2020.

Siani, G., Magny, M., Paterne, M., Debret, M., and Fontugne, M.: Paleohydrology reconstruction and Holocene climate variability in the South Adriatic Sea, Clim. Past, 9, 499–515, https://doi.org/10.5194/cp-9-499-2013, 2013.

Sinclair, D. J., Banner, J. L., Taylor, F. W., Partin, J., Jenson, J., Mylroie, J., Goddard, E., Quinn, T., Jocson, J., and Miklavič, B.: Magnesium and strontium systematics in tropical speleothems from the Western Pacific, Chemical Geology, 294–295, 1–17, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemgeo.2011.10.008, 2012.

Smith, D. E., Harrison, S., Firth, C. R., and Jordan, J. T.: The early Holocene sea level rise, Quaternary Science Reviews, 30, 1846–1860, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2011.04.019, 2011.

Thomas, E. R., Wolff, E. W., Mulvaney, R., Steffensen, J. P., Johnsen, S. J., Arrowsmith, C., White, J. W. C., Vaughn, B., and Popp, T.: The 8.2ka event from Greenland ice cores, Quaternary Science Reviews, 26, 70–81, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2006.07.017, 2007.

Tindall, J. C. and Valdes, P. J.: Modeling the 8.2 ka event using a coupled atmosphere–ocean GCM, Global and Planetary Change, 79, 312–321, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloplacha.2011.02.004, 2011.

Tinner, W. and Lotter, A. F.: Central European vegetation response to abrupt climate change at 8.2 ka, Geol., 29, 551, https://doi.org/10.1130/0091-7613(2001)029<0551:CEVRTA>2.0.CO;2, 2001.