the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Carbon export and burial pathways driven by a low-latitude arc-continent collision

Thierry Adatte

Shraddha Band

Romain Vaucher

Brahimsamba Bomou

Laszlo Kocsis

Pei-Ling Wang

Samuel Jaccard

Chemical weathering of silicate rocks of low-latitude arc–continent collisions has been hypothesized as a driver of global cooling since the Neogene. In mid- to low-latitude regions, monsoon and tropical cyclone precipitation also drive intense physical erosion that contribute to terrestrial carbon export and nutrient-stimulated marine productivity. Despite this, the role of physical erosion on carbon sequestration has largely been overlooked. To address this gap, we analyse late Miocene–early Pleistocene sedimentary and geochemical records from the Taiwan Western Foreland Basin and time-equivalent records from the northern South China Sea.

Along the continental slope, organic carbon accumulation is largely controlled by long-term sea-level fall and shoreline progradation. In contrast, on the continental rise, organic carbon burial is controlled by high sedimentation rates related to Taiwan's uplift and erosion (since ∼ 5.4 Ma). Despite increased terrestrial erosion of Taiwan, the organic material remains mainly marine in origin, suggesting that primary production was enhanced along the coast by nutrient exported from Taiwan. Marine organic matter along Taiwan's shore was subsequently remobilized by turbidity currents through submarine canyon systems and accumulating on the continental rise of Eurasia. The onset of Northern Hemisphere Glaciation (∼ 3 Ma) and subsequent intensification of the East Asian Summer Monsoon during interglacial periods, and persistent tropical cyclone activity all further amplified nutrient export across the basin, further stimulating marine primary production.

Our findings demonstrate that arc–continent collision influences carbon sequestration through two pathways: (1) direct burial of terrestrial organic matter and (2) nutrient-fuelled marine productivity and burial. This work establishes a direct link between the erosion of an arc-continent collision and long-term carbon burial in adjacent ocean basins.

- Article

(5308 KB) - Full-text XML

-

Supplement

(810 KB) - BibTeX

- EndNote

Global cooling since the late Eocene has traditionally been attributed to tectonic forcing and enhanced chemical weathering of silicate rock from the Himalayan and Tibetan Plateau (Raymo and Ruddiman, 1992), which results in the removal of atmospheric CO2 (Walker et al., 1981). However, weathering fluxes have decreased in both regions during the Neogene (Clift and Jonell, 2021; Clift et al., 2024a), and global silicate fluxes appear to have remained near steady-state through the Cenozoic (Caves et al., 2016) even as global cooling continued. To reconcile stable or declining chemical weathering rates with decreasing atmospheric CO2, an alternative hypothesis emphasized chemical erosion of arc-continent collisional orogens in low-latitude, tropical regions (Clift et al., 2024b; Jagoutz et al., 2016; Macdonald et al., 2019; Bayon et al., 2023). In such environments, warm and humid conditions amplify chemical weathering, enhancing carbon removal and sequestration. While existing studies support a correlation between the growth and weathering of low-latitude orogens and long-term atmospheric CO2 concentration and global temperature records, they have yet to fully account for the roles of physical erosion, terrestrial organic carbon burial, and changes in marine productivity.

In low-latitude regions, tropical cyclones and monsoons are the primary drivers of erosion and sediment dispersal, delivering elevated sediment loads to adjacent seas via intense precipitation and high river discharge from steep mountainous catchments (Chen et al., 2018; Milliman and Kao, 2005). Warm sea-surface temperatures and reduced polar ice volumes under greenhouse climates would likely amplify monsoon variability and produce frequent and intense tropical cyclones (Fedorov et al., 2013). These conditions of elevated humidity and precipitation would have promoted not only enhanced chemical weathering of silicate rocks, but also greater terrestrial biomass production.

Land-to-sea export of terrestrial organic material from vegetation, soil, and rock is enhanced under high precipitation regimes, with steep mountain rivers efficiently transporting this material for burial in adjacent ocean basins (Milliman et al., 2017; Hilton et al., 2011). The global terrestrial carbon pool accounts for ∼ 7.5 % of the Earth's total carbon stock, excluding lithospheric carbon, and is more than five times larger than the atmospheric carbon pool (Canadell et al., 2021). As a result, even modest changes in the terrestrial carbon storage can significantly alter atmospheric CO2 concentrations (Houghton, 2003). In particular, physical erosion by water is widely recognized as a dominant control of land–atmosphere carbon exchange (Hilton and West, 2020; Van Oost et al., 2012). Elevated sediment discharge to the oceans would facilitate the export and burial of terrestrial organic carbon (Galy et al., 2007; Hilton et al., 2011; Liu et al., 2013; Aumont et al., 2001; Dagg et al., 2004; Jin et al., 2023), and also deliver bioessential nutrients that stimulate marine productivity (Hoshiba and Yamanaka, 2013; Krumins et al., 2013; Dürr et al., 2011; Beusen et al., 2016). However, the role of fluvial nutrient export in fuelling marine primary productivity is generally thought to be limited to coastal regions (Froelich, 1988; Stepanauskas et al., 2002; Dagg et al., 2004). This oversimplification in ocean biogeochemical models leads to a poorly constrained link between terrestrial nutrient supply, open-ocean productivity, and deep-sea carbon burial.

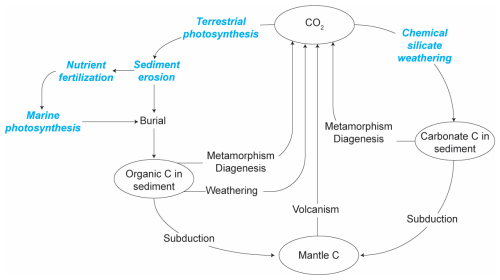

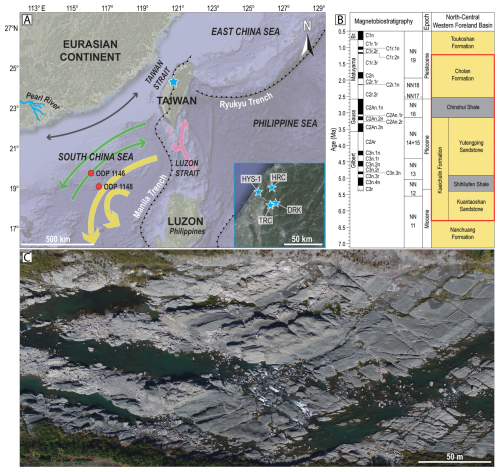

This research aims to address these knowledge gaps by disentangling the different mechanisms through which carbon is sequestered as a result of low-latitude arc-continent collisions (Fig. 1). A clearer understanding of these processes will provide stronger constraints on both reconstructed and predictive carbon budget models. The study area focuses on the northern South China Sea (SCS) region, specifically late Miocene to early Pleistocene (∼ 6.3–2 Ma) strata of the Taiwan Western Foreland Basin (TWFB, i.e., paleo-Taiwan Strait; Fig. 2) and time-equivalent sediment core records obtained from the Ocean Drilling Program (ODP Sites 1146 and 1148; Fig. 2). Since its emergence in the early Pliocene, Taiwan has been characterized by exceptionally high denudation rates and rapidly became the dominant sediment source to the adjacent TWFB, overwhelming contributions from southeast Eurasia (Hsieh et al., 2023b). Hyperpycnal flows triggered by intense precipitation transported Taiwan-derived sediments over 1000 km into the SCS, leaving a distinct signature in deep-sea deposits (Hsieh et al., 2024; Liu et al., 2012). Strata of the TWFB capture the evolution of the Taiwan Orogen (Lin and Watts, 2002), and thus provide insight into how changes in weathering and erosion processes modulated carbon burial in the SCS sediments across successive orogenesis stages.

Figure 1Conceptual model of geologic carbon (C) sources and sinks, modified from (Berner, 2003). This research focuses on two main pathways of carbon sequestration often associated with arc-continent collisions, highlighted in blue: (1) direct burial of terrestrial organic matter, and (2) nutrient-fuelled marine productivity followed by the burial of marine organic matter. These processes play a crucial role in the long-term carbon cycle and the regulation of atmospheric CO2.

Figure 2(A) Map of the study area showing the locations of the Late Miocene–Early Pleistocene records from Ocean Drilling Program (ODP) sediment cores (orange circles) in the South China Sea, and outcrop locations from the Taiwan Western Foreland Basin (TWFB, blue stars). The inset map outlined in blue show the locations of the borehole (HYS-1) and outcrop locations (DRK = Da'an River, Kueichulin Formation; TRC = Tachia River, Chinshui Shale; HRC = Houlong River, Cholan Formation) of the TWFB strata used in this study. Modern-day circulation in the SCS is shown in arrows: black = alongshore surface current, green = surface- and intermediate-water currents, yellow = deep- and bottom-water current, pink = Kuroshio current, pink (dashed) = Taiwan warm current (modified from Hu et al., 2010; Liu et al., 2010a; Liu et al., 2016; Yin et al., 2023). (B) Chronostratigraphy of the TWFB is modified after Chen (2016), Hsieh et al. (2023a), and Teng et al. (1991). The red box highlights the targeted study section. Yellow denotes sandstone-dominated strata, and grey indicates mudstone-dominated strata. (C) Outcrop photo of the Chinshui Shale at Tachia River (this study).

The base of the TWFB stratigraphic fill is composed of the Kueichulin Formation, a sandstone-dominated unit deposited between the late Miocene–early Pliocene in shallow-marine and deltaic environments under the influence of wave and tidal processes, and composed of three members (from base to top): the Kuantaoshan Sandstone, Shihliufen Shale, and Yutengping Sandstone (Fig. 2; Castelltort et al., 2011; Nagel et al., 2013; Hsieh et al., 2025). Overlying the Kueichulin Formation is the Chinshui Shale, a mudstone-rich succession deposited in the late Pliocene with uncommon wavy-laminated sandstone interbeds that accumulated in an offshore setting during a phase of maximum flooding and enhanced subsidence in the TWFB (Castelltort et al., 2011; Nagel et al., 2013; Pan et al., 2015). The Chinshui Shale is overlain by the Cholan Formation during the early Pleistocene, which consists of heterolithic sediments deposited in shallow-marine environments influenced by waves, rivers, and tides (Covey, 1986; Nagel et al., 2013; Pan et al., 2015; Vaucher et al., 2023a).

The time interval between ∼ 6.27 and 1.95 Ma was targeted because it spans the initiation of Taiwan's emergence and uplift by the ongoing Eurasian-Philippine plate collision. It also includes the Pliocene (5.33–2.58 Ma), which may be the most recent time in Earth's history when atmospheric CO2 last reached or exceeded present-day concentrations (> 400 ppm; Tierney et al., 2019), and the subsequent transition toward Pleistocene icehouse conditions. Additionally, since tectonic configurations, insolation, and major floral and faunal assemblages have remained broadly unchanged since the mid-Pliocene (Dowsett, 2007; Robinson et al., 2008), this period also provides a critical Earth system analogue for evaluating future climate hazards (e.g., Burke et al., 2018), including sea-level rise and extreme weather events.

3.1 Data acquisition and analysis

A total of 553 samples were collected from outcrops of the TWFB exposed along rivers in southwestern Taiwan, including 272 collected from the Kueichulin Formation by Dashtgard et al. (2021) and Hsieh et al. (2023b) along the Da'an River (Fig. 2A). This was combined with new data from the Chinshui Shale (n = 90; Tachia River) and the Cholan Formation (n = 191; Houlong River) (Fig. 2A). Data between 4.13 and 3.15 Ma are not available as no outcrop sections were accessible. Gamma-ray data were obtained from the HYS-1 borehole drilled through the TWFB. Age-equivalent material was also obtained from deep-sea sediment cores ODP Site 1146 (19°27.40′ N, 116°16.37′ E, 2092 m water depth, 179.8–343.1 m core depth; Holbourn et al., 2005, 2007) and Site 1148 (18°50.169′ N, 116°33.939′ E, 3294 m water depth, 118.9–206 m core depth; Tian et al., 2008; Cheng et al., 2004), archived in international core repositories. Sampling resolution averaged ∼ 1.4 m vertically through the TWFB stratigraphic sections, and ∼ 0.65 and ∼ 0.35 m through the ODP Sites 1146 and 1148 cores, respectively.

Samples from the Chinshui Shale and ODP sites were analysed for organic geochemistry and paleomagnetism. For the Chinshui Shale, total organic carbon (TOC) and total nitrogen (TN) concentrations were determined from pulverized rock samples in the Department of Geosciences at National Taiwan University (NTU) using an elemental analyser (Elementar TOC analyser soli TOC® cube; Lin et al., 2025). Total carbon (TC) and TN abundances for ODP samples were determined with a CHNS Elemental Analyser (Thermo Finnigan Flash EA 1112) at the Institute of Earth Sciences (ISTE) at the University of Lausanne in Switzerland on oven-dried sieved and crushed sediment samples. The samples were heated to 900 °C, after which the combustion products were extracted into a chromatographic column where they were converted into simpler components: CO2 and N2. These components were then measured by a thermal conductivity detector, and the results were expressed as a weight percentage. Analytical precision and accuracy were determined by replicate analyses and by comparison with an organic analytical standard composed of purified L-cysteine, achieving a precision of better than 0.3 %. Organic matter (OM) analyses of ODP core samples were performed on whole-rock powdered samples using a Rock-Eval 6 at the ISTE following the method described by Espitalie et al. (1985) and Behar et al. (2001). Measurements were calibrated using the IFP 160000 standard. Rock-Eval pyrolysis provides parameters such as hydrogen index (HI, mg HC g−1 TOC, HC = hydrocarbons), oxygen index (OI, mg CO2 g−1 TOC), Tmax (°C), and the TOC (wt %). HI, OI and Tmax values, which give an overall measure of the type and maturation of the organic matter (e.g., Espitalie et al., 1985), cannot be interpreted for TOC < 0.2 wt % and S2 values ≥ 0.2 mg HC g−1. Total organic carbon accumulation rates (mg cm−2 kyr−1) for the ODP sites were calculated by multiplying mass-accumulation rates (MAR) derived from literature and TOC.

Organic carbon isotopic compositions (δ13Corg, ‰ relative to Vienna Pee Dee Belemnite) were measured by flash combustion on an elemental analyser (EA) coupled to an isotope-ratio mass spectrometer (IRMS) from pulverized, decarbonated (10 % HCl treatment) whole-rock samples. Samples from ODP sites were analysed at the Institute of Earth Surface Dynamics, University of Lausanne, using a Thermo EA IsoLink CN connected to a Delta V Plus isotope ratio mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Bremen), both operated under continuous helium flow. The samples and standards are weighed in tin capsules and combusted at 1020 °C with oxygen pulse in a quartz reactor filled with chromium oxide (Cr2O3) and below with silvered cobaltous-cobaltic oxide. The combustion produced gases (CO2, N2, NOx and H2O) are carried by the He-flow to a second reactor filled with elemental copper and copper oxide wires kept at 640 °C to remove excess oxygen and reduce non-stoichiometric nitrous products to N2. The gases are then carried through a water trap filled with magnesium perchlorate (Mg(ClO4)). The dried N2 and CO2 gases are separated with a gas chromatograph column at 70 °C and then carried to the mass spectrometer. The measured δ13C values are calibrated and normalized using international reference materials and in-house standards (Spangenberg, 2016). Samples from the Chinshui Shale were analysed at the Stable Isotope Laboratory at National Taiwan University using a Flash EA (Thermo Fisher Scientific) coupled to a Delta V Advantage (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The δ13C values are calibrated using an international reference material, IAEA-CH-3. The reproducibility and accuracy are better than ± 0.1 ‰.

Thirty-three oriented palaeomagnetic core specimens (25 mm diameter) were collected at ∼ 3.5 m intervals from unweathered, mud-rich beds from the Chinshui Shale, then prepared and analysed at Academia Sinica in Taiwan following the methodology described in Horng (2014). Cores were cut into 2 cm samples, and bulk magnetic susceptibility measured using a Bartington Instruments MS2B magnetic susceptibility meter. Mass-specific magnetic susceptibility (χ) was then derived by normalising bulk magnetic susceptibility to sample mass.

Existing data for the ODP sites 1146 and 1148 were also compiled from literature, including clastic MAR (Site 1146 from Wan et al., 2010a, Site 1148 from Wang et al., 2000b), magnetic susceptibility (1146 from Wang et al., 2005b, 1148 from Wang et al., 2000b), hematite goethite ratios (Hm Gt) derived from spectral reflectance band ratios at 565 435 nm (1146 from Wang et al., 2000a, 1148 from Clift, 2006), continuous gamma-ray logs (1146 from Wang et al., 2000a, 1148 from Wang et al., 2000b), and titanium calcium ratios (Ti Ca; 1146 from Wan et al., 2010a, 1148 from Hoang et al., 2010). Magnetic susceptibility and Ti Ca serve as proxies for physical erosion, recording variations in terrigenous sediment flux linked to summer monsoon precipitation. Intensified precipitation enhances basin sediment accumulation rates (Clift et al., 2014), and typically increases the magnetic susceptibility of marine sediment via enhanced runoff and terrestrial input (Clift et al., 2002; Kissel et al., 2017; Tian et al., 2005). In the SCS, magnetic susceptibility also serves as a sediment provenance indicator. Along the Taiwan Strait, sediment sourced from western Taiwan yields χ values that range from 0.9 ± 0.3 to 1.8 ± 0.5 × 10−7 m3 kg−1, much lower than those sourced from the South China Block (4.0 ± 1.3 × 10−7 m3 kg−1), indicating a relative depletion of magnetic minerals in Taiwan-sourced material (Horng and Huh, 2011). Titanium, associated with heavy mineral deposition, and calcium, linked to pelagic biogenic carbonate accumulation, yield Ti Ca values that increase with enhanced monsoon-driven sediment export (Clift et al., 2014). Gamma-ray intensities broadly track changes in lithology (Green and Fearon, 1940; Schlumberger, 1989), where values < 75 American Petroleum Institute (API) typically mark sandstone-rich intervals, > 105 API mudstone-rich intervals, and intermediate values reflect mixed lithologies. Increased sediment export, particularly of coarser grains, may be expressed as lower API values.

Sedimentary TOC content provides a measure of organic carbon accumulation through time. Terrestrial and marine sources can also be differentiated by their δ13Corg values (Dashtgard et al., 2021; Hilton et al., 2010; Chmura and Aharon, 1995; Peterson and Fry, 1987; Martiny et al., 2013). Marine organic matter (e.g., plankton, particulate and dissolved organic matter) typically have more enriched values than terrestrial inputs (e.g., C3 and C4 plants, and soil and lithogenic organic carbon) (Table 1). Marine-derived organic matter mainly accumulates on the seafloor under fair-weather conditions, while terrestrial input increases under intervals of increased precipitation and erosion (Hsieh et al., 2023b; Dashtgard et al., 2021).

Table 1Typical values for marine- and terrestrially sourced δ13Corg and C N (compiled by Dashtgard et al., 2021). Numbers in brackets represent sample count. OM = organic material.

Hematite-to-goethite (Hm Gt) ratios are widely applied as indicator of monsoon precipitation (Clift, 2006; Liu et al., 2007; Zhang et al., 2009). Hematite typically forms through iron oxidation under arid climates or seasonal climates with dry seasons, whereas goethite preferentially develops under humid climates (e.g., Kämpf and Schwertmann, 1983; Maher, 1986). In the northern SCS, however, Clift et al. (2014) documented a positive relationship between elevated Hm Gt values and intensified East Asian Summer Monsoon (EASM) rainfall and seasonality. Beyond climate, hematite also reflects sediment provenance: sediment derived from Taiwan is notably depleted in hematite and enriched in pyrrhotite (Horng and Huh, 2011). Locally estimated scatterplot smoothing (LOESS) is applied to all data to reveal trends through the studied time interval (Cleveland et al., 1992).

3.2 Age models

The chronostratigraphic framework for the Kueichulin Formation, Chinshui Shale, and Cholan Formation of the TWFB was established by astronomically tuning the gamma-ray records to the δ18O record of Wilkens et al. (2017), Hsieh et al. (2023a), Vaucher et al. (2023b). However, the boundary between the top of the Kueichulin Formation and the base of the Chinshui Shale is not well-established. Therefore, a magnetobiostratigraphic age model was developed from nannofossil zones and magnetic reversals identified in oriented outcrop core samples from the Chinshui Shale outcrop using the methodology described in Horng (2014) to ground-truth the existing framework. The remanent magnetic intensity, and declination and inclination of oriented core samples were measured using a JR-6A spinner magnetometer (AGICO). To determine the stable remanent magnetization and polarity (i.e., normal or reversed) of each sample, unstable secondary magnetization was removed by thermally demagnetizing the samples stepwise from 25 to 600 °C. The characteristic remanent magnetization (ChRM) declination and inclination of thermally demagnetized samples were calculated using principal component analysis with a minimum of three demagnetization steps in the PuffinPlot software (Lurcock and Wilson, 2012) to determine the polarity of each sample. Thermal demagnetization diagrams for the Chinshui Shale samples showing the stable remanent magnetic declinations and inclinations after principal component analysis are presented in Fig. S1 in the Supplement.

Index nannofossils and corresponding biozonations identified by Shea and Huang (2003) for the Chinshui Shale were used to constrain paleomagnetic polarities. The resulting age model was then correlated to an orbitally tuned, benthic foraminiferal, stable oxygen isotope (δ18O) record from the equatorial Atlantic Ocean (Wilkens et al., 2017), which is tied to physical sedimentary properties independent of ice volume, and has a robust timescale. Variations in both parameters are assumed to be causally linked and temporally in-phase.

The age model for ODP Site 1146 (Wan et al., 2010a) was constructed by linear interpolation between magnetobiostratigraphic age control points established by Wang et al. (2000a). Stratal ages from ODP Site 1148 are constrained using biostratigraphic ages of benthic foraminifera (Wang et al., 2000b).

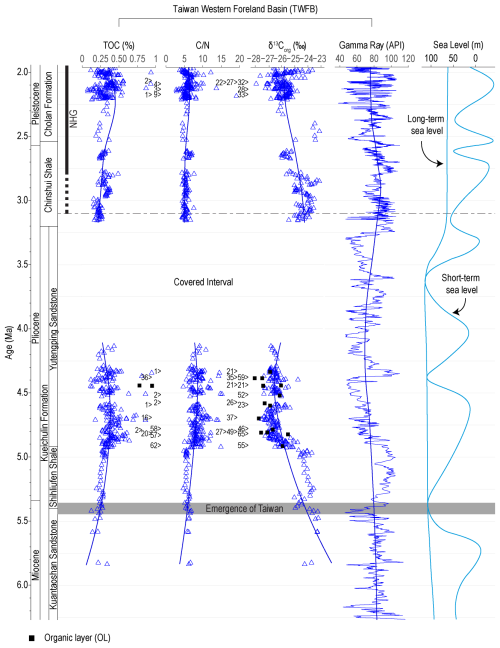

Data collected from the Chinshui Shale (n = 90) for this study have average TOC values (0.3 ± 0.1 %) comparable to those of the Shihliufen Shale (0.3 ± 0.03 %, n = 31), but are higher than the basal Kuantaoshan Sandstone (0.2 ± 0.1 %, n = 9), and lower than the Yutengping Sandstone (0.4 ± 0.1 %, n = 216) and the Cholan Formation (0.4 ± 0.7 %, n = 191; Fig. 3). C N and δ13Corg values of the Chinshui Shale (5.2 ± 0.7 ‰ and −24.5 ± 0.7 ‰, respectively) indicate stable accumulation of marine organic content, similar to the Shihliufen Shale (5.3 ± 0.4 ‰ and −24.2 ± 0.4 ‰) in contrast to the Kuantaoshan Sandstone (6.1 ± 0.3 ‰, −23.4 ± 0.3 ‰), Yutengping Sandstone (8.5 ± 1.8 ‰, −26.5 ± 0.5 ‰), as well as the overlying Cholan Formation (6.3 ± 4.1 ‰, −25.7 ± 0.8 ‰), which records enhanced terrestrial input (Fig. 3). The accumulation of marine organic matter is also stable through the Shihliufen Shale and the Chinshui shale, with greater variability between ∼ 4.9 and 4 Ma (Yutengping Sandstone), and after ∼ 2.3 Ma (Cholan Formation; Fig. 3).

Figure 3Compilation of total organic carbon (TOC), C N, δ13Corg, and gamma ray data for the Taiwan Western Foreland Basin (TWFB), including the Kueichulin Formation (Dashtgard et al., 2021; Hsieh et al., 2023b, a), the Chinshui Shale (this study and gamma-ray from Vaucher et al., 2023b), and the Cholan Formation (this study and gamma-ray from Vaucher et al. 2023b). Sea-level curves are from Haq and Ogg (2024). “>” indicates data that plot outside of the diagram. The solid lines represent curves fitted using locally estimated scatterplot smoothing (LOESS). TOC, C N, and δ13Corg trends reflect organic carbon sources, and show that marine organic matter content is high in the Kuantaoshan Sandstone, Shihliufen Shale, and Chinshui Shale, contrasting with increased terrestrial input in the Yutengping Sandstone and Cholan Formation. Gamma-ray data indicate lithological variability, and correlate with sea-level changes.

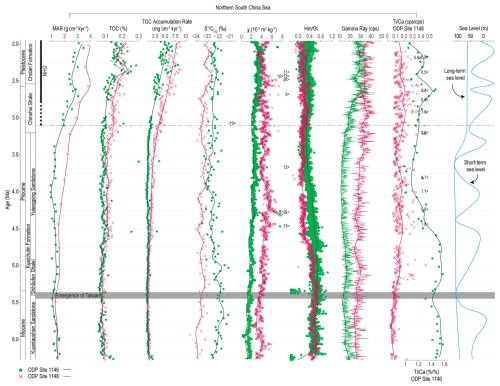

At ODP Site 1146 (Fig. 4), MAR (n = 59) and TOC (n = 225) values remain relatively stable until ∼ 3.3 Ma (averaging 1.2 ± 0.2 g cm−2 kyr−1 and 0.08 ± 0.03 %, respectively), after which both increase, with a maximum MAR of 3.5 cm−2 kyr−1, and maximum TOC of 0.3 %, accompanied by greater TOC variability. This is reflected in the TOC accumulation rate (n = 225), which shows increasing trends also since ∼ 3.3 Ma, from an average of 9.6 ± 3.7 × 10−4 to 3.7 ± 1.8 × 10−3 mg cm−2 kyr−1. δ13Corg (n = 113) show a gradual decrease from ∼ 5.7–4 Ma from an average of −21.8 ± 0.4 ‰ to −22.2 ± 0.6 ‰, then stabilises. Magnetic susceptibility (n = 2747) increases through the record from an average of ∼ 1.6 ± 0.4 to 2.5 ± 1 × 10−5 m3 kg−1 from 5–3 Ma, with accelerated increase after ∼ 3 Ma. Hm Gt ratios (n = 8196) decrease gradually from ∼ 4.75–3 Ma (from an average of 0.56 ± 0.3 to 0.35 ± 0.1, before showing greater amplitude variability. Gamma-ray values (n = 2551) remain relatively stable (16.2 ± 3.3 API) until ∼ 3.2 Ma with when both values and amplitudes rise (26.7 ± 5.7 API). The Ti Ca record (% %, n = 53) shows an overall decreasing trend from ∼ 4.6–3.5 Ma from an average of 1.5 ± 0.07 to 1.2 ± 0.1.

At ODP Site 1148 (Fig. 4), MAR values (n = 15) remain stable with a slight increase at ∼ 5.5 Ma from an average of 1.4 ± 0.009 to 1.6 ± 0.2 g cm−2 kyr−1, followed by a sharper increase near ∼ 3.5 Ma to a maximum of 3.5 g cm−2 kyr−1. TOC values (n = 220), as well as TOC accumulation rates (n = 220), are stable from ∼ 6.27–4.7 Ma (averaging 0.08 ± 0.01 % and 1.1 ± 0.2 × 10−3 mg cm−2 kyr−1, respectively. Both TOC and TOC accumulation rates increase from ∼ 4.7–4.5 Ma to 0.11 ± 0.01 % and 1.9 ± 0.3 × 10−3 mg cm−2 kyr−1, then stabilize until ∼ 3.5 Ma, and then increased again (exceeding 0.2 % and 5 × 10−3 mg cm−2 kyr−1, respectively) with greater amplitude. MAR, TOC, and TOC accumulation rates also exceed values measured from Site 1146 since ∼ 4.7 Ma by 20 %–60 %. δ13Corg (n = 110) is broadly stable, increasing near ∼ 2.75 Ma from an average of −23.2 ± 0.3 ‰ to −22.8 ± 0.4 ‰. Magnetic susceptibility values (n = 1249) show a gradual increase from ∼ 5.4–4.3 Ma from an average of 3.6 ± 0.6 to 4.9 ± 0.8 × 10−5 m3 kg−1, then a decrease until ∼ 3.5 Ma to an average of 4.6 ± 1.2 × 10−5 m3 kg−1. The values remain low after ∼ 3.5 Ma, with amplitudes deceasing after ∼ 2.75 Ma. Hm Gt (n = 1678) declines from ∼ 5.4–4.6 Ma from an average of 0.61 ± 0.08 to 0.2 ± 0.06, then stabilizes and slightly increases from ∼ 3.2–2.9 Ma. Gamma-ray values (n = 1249) are high from ∼ 5.4–4.9 Ma, averaging 29.5 ± 3.8 API, then decrease and stabilize before rising again after ∼ 3.5 Ma to an average of 35 ± 4.2 API. The Ti Ca ratios (cps cps, n = 646) increase overall from ∼ 5.4 Ma, from an average of 0.07 ± 0.03 to 0.16 ± 0.1, with increasing amplitude variability.

Figure 4Compilation of sediment core data from ODP Sites 1146 and 1148 in the northern South China Sea, including mass accumulation rate (MAR; Wan et al., 2010a; Wang et al., 2000b), TOC and δ13Corg (this study), mass-specific magnetic susceptibility (χ; Wang et al., 2005b; Wang et al., 2000b), hematite goethite (Hm Gt; Wang et al., 2000a; Clift, 2006), gamma ray (Wang et al., 2000a, b), and Ti Ca (Wan et al., 2010a; Hoang et al., 2010). Sea-level curves are from Haq and Ogg (2024). “>” indicates data that plot outside of the diagram. The solid lines represent curves fitted using locally estimated scatterplot smoothing (LOESS). The figure illustrates the contrasting sedimentary and geochemical responses between the two ODP sites, driven by tectonic uplift, climate variability, and changes in ocean circulation.

5.1 Spatial variability in sediment provenance and distribution in the northern South China Sea

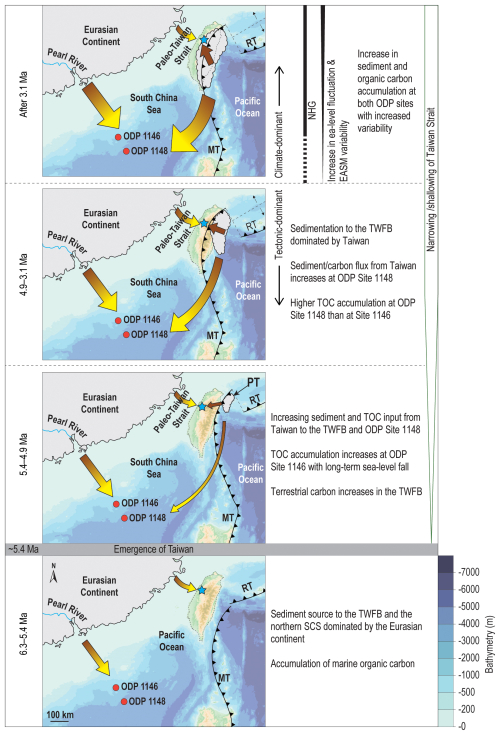

Provenance exerts a first-order control on sedimentary records in the SCS, owing to the region's complex geology and active tectonism, which channels sediment contributions from multiple major rivers (e.g., Clift et al., 2014, 2022; Horng and Huh, 2011; Kissel et al., 2016, 2017; Liu et al., 2009c, 2007, 2010b, 2016; Wan et al., 2010c; Milliman and Syvitski, 1992). During most of the Neogene, the Pearl River supplied the dominant sediment flux to the northern SCS (Clift et al., 2002; Li et al., 2003). The emergence of the Taiwan orogen in the early Pliocene fundamentally reorganised this system: by ∼ 5.4 Ma, and especially after ∼ 4.9 Ma, Taiwan had become a major sediment source to the adjacent TWFB and the wider SCS, as a result of rapid uplift and intense erosion and south-westward collision-zone migration (Fig. 5; Liu et al., 2010b; Hsieh et al., 2023b; Hu et al., 2022). This change in sediment provenance is tectonically driven and underscores the need to disentangle tectonic from climatic signals in SCS sedimentary archives (Clift et al., 2014; Hsieh et al., 2024).

Figure 5Summary of different controls on sediment and carbon accumulation over time in the Taiwan Western Foreland Basin (blue star) and the ODP sites (orange circles) in the northern South China Sea. The size of the arrows indicates relative proportions of sediment flux, and brown indicates accumulation of terrestrial organic carbon, while yellow indicates marine organic carbon. The abbreviations MT = Manilla Trench, RT = Ryukyu Trench, and PT = proto-Taiwan. These differences in organic carbon source (i.e., terrestrial vs. marine) and carbon accumulation highlight the spatial heterogeneity in sedimentary and geochemical records within the northern South China Sea, shaped by the interplay of tectonic and climatic processes. Bathymetric map from GEBCO Bathymetric Compilation Group (2025).

This diversity in sediment sources and mixing is reflected at ODP Sites 1146 and 1148, where the sediment records differ despite their spatial proximity. MAR, magnetic susceptibility, Hm Gt and gamma-ray records diverge between the two sites until ∼ 3 Ma (Fig. 4). At ODP Site 1146, located on the continental slope, sediments are primarily derived from Eurasia (Fig. 5). At Site 1146, major element and clay mineral compositions point to a mixture of sources dominated by the Pearl River, with additional inputs from the Yangtze River, Taiwan, Luzon, and loess (Wan et al., 2007a; Liu et al., 2003; Hu et al., 2022). Pearl River sediment deposition is controlled by long-term sea-level changes and East Asian Monsoon variability (e.g., Liu et al., 2016; Clift, 2006), but its delivery to the open basin is strongly constrained by alongshore and surface- to intermediate-water currents that funnel most material along the continental shelf and slope (Liu et al., 2010b, 2016; Wan et al., 2007a; Liu et al., 2009a).

In contrast, ODP Site 1148, located on the continental rise, records a stronger Taiwanese imprint (i.e., less contribution from Eurasia; Fig. 5). Prior to ∼ 6.5 Ma, major element data suggest a mixture of Pearl River and Taiwan inputs, but since the onset of Taiwan orogenesis (∼ 6.5 Ma), Taiwanese material has increasingly dominated (Hu et al., 2022). Isotopic (87Sr 86Sr, εNd) records, and clay mineralogy showing increasing illite with corresponding decreasing kaolinite near ∼ 5 Ma corroborate Taiwan as the dominant sediment contributor to the northern SCS since its emergence after ∼ 5.4 Ma (Bertaz et al., 2024; Boulay et al., 2005; Clift et al., 2014; Hsieh et al., 2023b). Erosion of modern and ancient Taiwan is primarily driven by tropical-cyclone precipitation (Dashtgard et al., 2021; Vaucher et al., 2021; Galewsky et al., 2006; Chen et al., 2010; Chien and Kuo, 2011; Janapati et al., 2019). Under warmer Pliocene climates (Fedorov et al., 2010; Yan et al., 2016) such storms were likely more frequent and intense (e.g., Yan et al., 2019), and especially if coinciding with EASM circulation, would have driven exceptionally high precipitation (Chen et al., 2010; Chien and Kuo, 2011; Kao and Milliman, 2008; Lee et al., 2015; Liu et al., 2008) and sediment export (Vaucher et al., 2023b). Sediment derived from Taiwan is subsequently redistributed into the northern SCS by downslope deep currents (Liu et al., 2010b, 2016; Hu et al., 2012; Liu et al., 2013). The emergence of Taiwan also reconfigured regional circulation, establishing a westward Kuroshio branch that delivered additional sediment from Taiwan and the Philippines (i.e., the Luzon Arc) into the northern basin (Liu et al., 2016).

The difference in sediment provenance and transport pathways between the continental slope and continental rise is reflected in the contrasting proxy trends observed at both ODP sites (Fig. 4). At ODP Site 1146, the long-term increase in magnetic minerals since ∼ 6.27 Ma reflects increased sediment input from Eurasia that is comparatively enriched in magnetic minerals than sediment from Taiwan (Horng and Huh, 2011; Hsieh et al., 2023b). Concurrently, low gamma-ray values and declining Ti Ca until ∼ 3 Ma also reflect increased delivery of sand-rich, clastic detritus, while the decreasing Hm Gt suggests a progressive weakening of the EASM rainfall and seasonality. Together, these proxy signals are consistent with global trends of long-term cooling and falling global mean sea level during this interval (Wan et al., 2007b; Haq et al., 1987; Miller et al., 2020; Westerhold et al., 2020; Holbourn et al., 2021; Berends et al., 2021; Rohling et al., 2014; Jakob et al., 2020; Haq and Ogg, 2024), as well as with evidence of diminished chemical weathering and progressive weakening of the EASM system (Clift et al., 2014; Wan et al., 2006, 2010a, b; Clift, 2025; Li et al., 2004; Wang et al., 2019). This interpretation is further supported by declining K Al ratios observed at ODP Site 1146 between 5 and 3.8 Ma by Tian et al. (2011), which likewise indicate reduced chemical weathering and a shift towards long-term drying, which began ∼ 10 Ma in the region (Clift, 2025; Clift et al., 2014).

At ODP Site 1148, MAR increases near the onset of Taiwan's orogenesis (∼ 5.4 Ma), corresponding to enhanced sediment export from rapid erosion of the emerging orogen. An increase in magnetic susceptibility is also observed ∼ 5.4–4.3 Ma (Fig. 4), consistent with the erosion of passive-margin seafloor sediments enriched in magnetic minerals that was uplifted during the early stages of Taiwan's orogenesis (Hsieh et al., 2023b). After ∼ 4.3 Ma, magnetic susceptibility declines, coinciding with the deposition of the Yutengping Sandstone and increasing influx of sediment derived from the metasedimentary core of Taiwan, which is comparatively depleted in magnetic minerals (Hsieh et al., 2023b). Unlike Site 1146, the Hm Gt record at Site 1148 does not appear to track long-term monsoon drying. Rather, the abrupt decrease in the Hm Gt record at ∼ 5.4 Ma is attributed to the influx of hematite-depleted sediment from Taiwan as it emerged from the Pacific Ocean. The dispersal of Taiwan-sourced sediment into the northern SCS was facilitated by deep-water currents and by the westward-flowing Kuroshio Branch, both of which developed following the formation of the Taiwan and Luzon straits during orogenesis. Changes in ocean circulation during the early to middle Pliocene are also captured by K Al records, which show contrasting trends between intermediate water depths (e.g., Site 1146) and deep water settings (e.g., Site 1148), which is interpreted as reflecting shifts in sediment dispersal pathways to the northern SCS (Tian et al., 2011). The subsequent rise in Hm Gt near ∼ 3.2 Ma is attributed to the northward remobilization of Taiwan-sourced sediment following the formation of the Taiwan Warm Current (Fig. 3; Hsieh et al., 2024). The gamma-ray record also tracks the orogenic evolution of Taiwan at ODP Site 1148 (Fig. 4) and parallels observations from the TWFB (Fig. 3): values are elevated during the deposition of mudstone-rich Shihliufen Shale, decrease during formation of sand-dominated Yutengping Sandstone and rise again with the deposition of mudstone-rich Chinshui Shale and Cholan Formation. The increase in sediment export from Taiwan is also reflected in the Ti Ca record, which increases after ∼ 5.4 Ma, in response to intensified physical erosion and elevated terrestrial flux linked to the onset of Taiwan orogenesis.

After ∼ 3 Ma, the onset of Northern Hemisphere Glaciation (NHG) resulted in enhanced seasonality and an intensification of the EASM (Fig. 5; Clift, 2025; Wan et al., 2006; Clift et al., 2014; Wan et al., 2007a, b). Although global cooling characterized the late Plio-Pleistocene (Lisiecki and Raymo, 2005), sea-surface temperatures in the northwest Pacific remained sufficiently high (26.5–27.0 °C) to sustain tropical cyclone activity (Tory and Frank, 2010). This combined influence of intensified EASM and frequent tropical-cyclone precipitation promoted elevated sediment production and large-scale export of fine-grained material enriched in TOC from river catchments into offshore depocenters. This is reflected in both sites by higher gamma-ray values, increased MAR, and rising Ti Ca ratios (Fig. 4). Enhanced seasonality is further expressed in the greater amplitude observed in gamma-ray, Hm Gt, and Ti Ca records.

5.2 Influence of terrestrial sediment export vs. primary production on carbon burial

Organic carbon buried in the SCS can be broadly divided into two components: (1) terrestrial organic matter derived from rock, soil, and terrestrial vegetation exported from adjacent landmasses by precipitation-driven erosion, and (2) marine organic matter produced by primary productivity and exported to the seafloor.

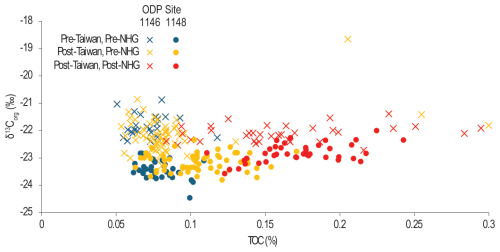

At Site 1146, organic carbon accumulation, like bulk sediment accumulation, is primarily controlled by long-term global sea-level fall associated with the onset and intensification of NHG (Fig. 5). Total organic carbon values are closely coupled with MAR, with increases in sediment flux consistently accompanied by higher TOC concentrations (Fig. 4). Although δ13Corg values show a modest decline between ∼ 5.7 and 4.5 Ma, which is consistent with episodic dilution by terrestrial organic inputs, values remain within the marine range (Table 1). The gradual increase in terrestrial organic matter at ODP Site 1146 is interpreted to reflect increased Eurasian clastic influx under conditions of long-term sea-level fall. The cross-plot of δ13Corg and TOC also shows no distinct shift between organic matter delivered to Site 1146 before and after the emergence of Taiwan. As sediment transported eastward from the Eurasian margin would have longer residence times in the ocean, the dilution of land-derived organic material by marine organic material would increase, resulting in a more marine δ13Corg signature (Dashtgard et al., 2021) which supports the interpretation that organic material is derived mainly from Eurasia via the Pearl River (Fig. 6).

Figure 6Cross-plot of δ13Corg and TOC measured from ODP Sites 1146 and 1148. Values are grouped according to major tectonic and climate changes: (1) pre-emergence of Taiwan and pre-Northern Hemisphere Glaciation, (2) post-emergence of Taiwan and pre-Northern Hemisphere Glaciation, and (3) post-emergence of Taiwan and post-Northern Hemisphere Glaciation. Note the distinct trends before and after Taiwan's emergence and Northern Hemisphere Glaciation. Site 1146 reflects Eurasian sediment input with marine organic matter dominance, while Site 1148 highlights Taiwan's influence, with enhanced marine productivity linked to nutrient export.

In contrast, carbon burial at Site 1148 is primarily linked to the uplift and erosion of Taiwan and associated increase in sediment and nutrient delivery to the marine environment (Fig. 5). The onset of Taiwan's emergence at ∼ 5.4 Ma coincides with a marked rise in MAR, followed by an increase in TOC beginning near ∼ 4.9 Ma (Fig. 4). This pattern reflects significant export of terrestrial sediment from the rapidly uplifting Taiwan orogen, a process further amplified by the coupling between tropical cyclone and monsoon precipitation (Vaucher et al., 2023b). Notably, TOC increases proportionally with MAR, implying that carbon burial was not diluted by high sediment flux but rather enhanced by intensified sediment export and/or better preserved by rapid burial, highlighting the role of Taiwan as a contributor of organic carbon in the northern SCS. The influence of sedimentation from Taiwan on organic matter buried at Site 1148 is also evident from the cross-plot between δ13Corg and TOC, which shows a distinct increase in TOC prior to and after the emergence of Taiwan (Fig. 6).

Taiwan's steep topography and active tectonics generate exceptionally high sediment yields to adjacent marine systems (Liu et al., 2013; Dadson et al., 2003, 2004). Turbidity currents, especially via submarine canyon systems (e.g., the Gaoping Submarine Canyon in southern Taiwan), efficiently transport organic-rich sediment eroded from Taiwan to deep-sea environments approximately 260 km offshore into the northeastern Manila Trench (Liu et al., 2009b, 2016; Zheng et al., 2017; Yu et al., 2009; Nagel et al., 2018). Within the TWFB, this process is manifested as an abrupt increase in terrestrial organic matter and sand-rich deposition near ∼ 4.9 Ma with the emplacement of the Yutengping Sandstone (Fig. 4). At Site 1148, TOC increases markedly in association with the emergence of Taiwan, and δ13Corg values remains stable above −25 ‰. While C4 plants are characterized by high δ13Corg values (Table 1), and an expansion of C4 plants in the South China region has been documented since 35 Ma (Li et al., 2023; Xue et al., 2024), the organic carbon at Site 1148 are interpreted to be of marine in origin as C3 plants remain the dominant vegetation type in the study area (Luo et al., 2024; Still et al., 2003; Wang and Ma, 2016). Furthermore, sediment provenance markers (Sect. 5.1) indicate an influx of Taiwan-sourced material to Site 1148 after the emergence of Taiwan, and δ13Corg values in the TWFB reflect an increase in terrestrial organic matter. The presence of Taiwan-sourced material combined with high proportions of marine organic carbon at Site 1148 suggests that terrestrial organic matter from Taiwan was largely confined to proximal coastal environments, and that enhanced carbon burial in deeper settings reflects processes beyond direct terrigenous input. Likewise, terrestrial organic matter contribution from the Pearl River into deeper-water depocenters is limited, as sediment is dispersed along the continental shelf by alongshore and shallow- to intermediate-water currents (Liu et al., 2010b, 2016; Wan et al., 2007a). During transport and sedimentation, degradation does not appear to significantly alter the isotopic composition of organic matter, since there is little fractionation between reactants and products. If post-depositional alteration were a dominant control, δ13Corg values should become progressively less negative with depth, as lighter isotopes are preferentially removed. However, the δ13Corg records from the two sites show distinct trends, suggesting that the influence of post-depositional isotopic fractionation is insignificant.

Taiwan's rapid denudation delivers large quantities of sediment and nutrients to the northern SCS, profoundly shaping basin productivity and carbon cycling. The export of bioessential nutrients stimulates intense coastal primary production, as reflected by modern chlorophyll-a and nitrogen distributions that peak along Taiwan's coast before rapidly declining offshore due to swift uptake (Kao et al., 2006; Ge et al., 2020; Huang et al., 2020). Episodic inputs from tropical cyclones, which contribute up to 80 % of summer particulate organic carbon, further amplify productivity and promote lateral dispersal of sediments (Liu et al., 2013). Marine organic matter produced through enhanced coastal productivity could be redistributed by deep-water contour currents and mesoscale eddies (Lüdmann et al., 2005; Zhang et al., 2014; Zhao et al., 2015; Hsieh et al., 2024), enabling its bypass into the deeper water depths and resulting in the marine signature of the δ13Corg records from the northern SCS.

Fluvial input from Taiwan, especially via submarine canyon systems, makes the northern SCS a depocenter for organic carbon burial, with important implications for the basin's sedimentary architecture, long-term carbon budget, and even hydrocarbon source rock potential (Kao et al., 2006). Paleoceanographic records indicate that productivity and organic carbon burial increased during glacial periods (Thunell et al., 1992), likely driven by nutrient delivery from Taiwan's sediments that enhanced the biological pump and contributed to regional carbon drawdown. In the modern setting, episodic sediment fluxes during typhoons sustain unusually high chlorophyll-a concentrations in deep SCS waters relative to the global ocean (Shih et al., 2019). Moreover, northeast monsoon-driven mixing between the China Coastal Current and Taiwan Strait Current, reinforced by sediment and nutrient inputs dominantly from Taiwan and the Yangtze River, sustains elevated productivity in the northern SCS (Huang et al., 2020). Collectively, these processes highlight Taiwan's sediment flux as a key linkage between monsoon forcing, nutrient cycling, and primary production across both modern and in the past.

5.3 Influence of climate and monsoon on carbon burial

In the TWFB, carbon geochemistry and gamma-ray data largely reflect the evolution of the foreland basin synchronously with the shifts in the regional climate regime (Fig. 3). During the deposition of the Chinshui Shale in the late Pliocene (∼ 3.2 to 2.5 Ma), reconstructions for the northwest Pacific show relatively high global sea levels and stable sea-surface temperatures (Li et al., 2011; Berends et al., 2021). Such conditions favoured the accumulation of fine-grained sediment, while elevated sea levels deepened the TWFB and promoted offshore depositional environments-both of which are expressed in the Chinshui Shale (e.g., Nagel et al., 2013; Vaucher et al., 2023b). Greater water depths and increased distance from the terrestrial sediment sources also enhanced the relative contribution of marine organic matter. The gamma-ray record of the TWFB strata further reveals depositional cycles related to interactions between EASM and tropical cyclone precipitation after ∼ 4.92 Ma, with variability expressed at both short-eccentricity and precession frequency bands (Vaucher et al., 2023b; Hsieh et al., 2023a).

During the early Pleistocene, with deposition of the Cholan Formation (∼ 2.5–1.95 Ma), global sea level and regional sea-surface temperatures became markedly more variable (Li et al., 2011; Berends et al., 2021). The continued uplift and southwest migration of Taiwan promoted the development of shallow-marine depositional environments recorded in the Cholan Formation (e.g., Pan et al., 2015; Vaucher et al., 2021, 2023a, b). This is expressed in the gamma-ray and carbon records as an increase in terrestrially sourced, sandstone-rich intervals with high variability (Fig. 3). The enhanced export of coarser-grained sediment from land to sea is likely related to the onset of NHG, when repeated sea-level minima promoted clastic delivery to the basin (Vaucher et al., 2021, 2023b).

In addition, global climate deterioration related to NHG intensified and destabilised the EASM (Wan et al., 2006, 2007a). Paleoclimate reconstructions from East Asia document a strengthening of the EASM during the late Pliocene, generally near ∼ 3.5 Ma (Zhang et al., 2009; Yang et al., 2018; Yan et al., 2018; Xin et al., 2020; Nie et al., 2014; Hoang et al., 2010). While the causal relationship between monsoon intensity and NHG remains debated (Zhang et al., 2009; Xin et al., 2020; Wan et al., 2010b; Nie et al., 2014), long-term global cooling and sea-level fall coupled with monsoon and tropical cyclone precipitation likely acted together to amplify sediment export from land to sea (Vaucher et al., 2023b). In the northern SCS, MAR and TOC values and amplitudes at both ODP sites increased after ∼ 3 Ma, consistent with increased sediment export (Figs. 4, 5). At the same time, δ13Corg values at ODP Site 1148 increases after ∼ 3 Ma, suggesting increasing marine contribution to organic carbon. This trend is attributed to enhanced marine primary production driven by nutrient enrichment. Independent evidence for increased marine primary productivity in this interval comes from elevated abundances of planktonic foraminifera Neogloboquadrina dutertrei and higher biogenic silica production (Wang et al., 2005a).

Analyses of late-Miocene to early Pleistocene sedimentary and geochemical records from shallow-marine strata of the Taiwan Western Foreland Basin and deep-sea sediment cores from the northern South China Sea (SCS) provide clear evidence for shifting pathways of carbon erosion, transport, and burial shaped by the interplay between tectonic forcing, climate variability, and oceanographic processes.

Sediment provenance reveals marked spatial heterogeneity between the continental slope (ODP Site 1146) and the continental rise (ODP Site 1148), highlighting the influence of tectonic uplift and evolving ocean circulation on sediment mixing and deposition. Prior to ∼ 5.4 Ma, sediment delivery to the northern SCS was dominated by Pearl River discharge. Taiwan's rapid emergence and erosion at ∼ 5.4 Ma supplied large volumes of clastic material to the basin, which is expressed in sediment provenance records at Site 1148, whereas Site 1146 remained strongly influenced by Eurasian sources. Pearl River sediments were dispersed along the continental shelf and slope by alongshore and shallow- to intermediate-water currents but were largely obstructed from reaching deeper water depths by the northward-flowing Kuroshio Current and the shallow Taiwan Strait.

The onset of Northern Hemisphere Glaciation (NHG; ∼ 3 Ma) further amplified sediment erosion and export across the basin. Long-term global cooling and sea-level fall, coupled with enhanced seasonality, drove the intensification of the East Asian Summer Monsoon. The resulting increase in monsoon rainfall, as well as persistent tropical cyclone activity, drove synchronous increases in mass-accumulation rate (MAR), magnetic susceptibility, and Ti Ca values at both ODP sites, demonstrating the strong climatic imprint on sediment export. In addition, slightly higher δ13Corg values after ∼ 3 Ma indicate a greater marine contribution to organic matter, attributed to enhanced nutrient-driven marine primary production.

Organic carbon burial likewise reflects the combined influence of tectonic and climate forcing. At ODP Site 1146, total organic carbon (TOC) accumulation parallels MAR and is primarily controlled by long-term sea-level fall and NHG intensification. δ13Corg values indicate that the bulk of organic matter remained marine in origin, with minor terrestrial contribution linked to Eurasian sediment export rather than to Taiwan's orogenesis. At ODP Site 1148, by contrast, organic carbon burial is closely tied to the Taiwan's uplift and erosion. Importantly, TOC scales proportionally with MAR, implying that organic matter burial was enhanced – not diluted – by high sediment flux. Despite Taiwan's steep relief, rapid tectonic uplift, and frequent typhoon- and monsoon-driven erosion generating exceptional sediment yields, δ13Corg values indicate that most buried organic carbon was marine. This suggests that Taiwan's erosion enhanced nutrient supply, stimulating coastal primary productivity. Marine organic matter produced in these settings was then redistributed offshore by turbidity currents through submarine canyon systems, bypassing the shelf and slope and accumulating in deep-sea depocenters of the northern SCS.

Overall, this study highlights the importance of resolving spatial heterogeneities in sedimentary climate archives. Disentangling the competing influences of tectonics and climate on sediment supply and carbon burial is critical for robust intercomparison of paleoclimate records, and for reconciling apparent inconsistencies among proxy reconstructions. Our findings also demonstrate that terrestrial sediment export contributes to carbon drawdown via two distinct pathways: (1) direct burial of eroded terrestrial organic matter and (2) nutrient supply that fuels marine primary production and subsequent burial of marine organic matter. This work establishes a direct link between the tectonic evolution of an arc-continent collisional orogen and changes in carbon storage in adjacent basins, and disentangles the mechanisms by which the erosion of mid-latitude orogens contributed to long-term carbon sequestration.

The data that support the findings of this study can be found on Zenodo at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.18397150 (Hsieh, 2026).

The supplement related to this article is available online at https://doi.org/10.5194/cp-22-227-2026-supplement.

AIH. was responsible for the design and conceptualization of this study, supervised by SJ. Data collection was completed by AIH, SB, and RV. AIH, TA, LL, BB, LK, and PLW were responsible for sample analysis. TA, LL, SB, RV, and SJ provided support in the interpretation of sedimentary paleoenvironmental proxies. All co-authors reviewed and approved the manuscript.

The contact author has declared that none of the authors has any competing interests.

Publisher's note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims made in the text, published maps, institutional affiliations, or any other geographical representation in this paper. The authors bear the ultimate responsibility for providing appropriate place names. Views expressed in the text are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher.

We would like to thank Dr. Yusuke Kubo at the Japan Agency for Marine-Earth Science and Technology for access to the ODP Site 1146 and 1148 core samples. This research was supported financially through the Institute of Earth Sciences Postdoctoral fellowship awarded to Amy I. Hsieh from the University of Lausanne. Romain Vaucher acknowledges the Swiss National Science Foundation Postdoc.Mobility Grant (P400P2_183946) which supported him during data collection from the Cholan Formation. We express our gratitude to Kuo-Hang Chen for supporting the magnetostratigraphic analysis, Tiffany Monnier for assisting in sample processing and analysis, and Ling-Wen Liu for elemental and isotope analyses. We are grateful for the constructive feedback from an anonymous referee and Prof. Shannon Dulin, as well as the support from the editor, Prof. Lynn Soreghan, who helped to greatly improve this manuscript.

This research has been supported by the Institute of Earth Sciences Postdoctoral fellowship from the University of Lausanne, and the Swiss National Science Foundation Postdoc.Mobility Grant (P400P2_183946).

This paper was edited by Gerilyn (Lynn) Soreghan and reviewed by Shannon Dulin and one anonymous referee.

Aumont, O., Orr, J. C., Monfray, P., Ludwig, W., Amiotte-Suchet, P., and Probst, J.-L.: Riverine-driven interhemispheric transport of carbon, Global Biogeochem. Cy., 15, 393-405, https://doi.org/10.1029/1999GB001238, 2001.

Bayon, G., Patriat, M., Godderis, Y., Trinquier, A., De Deckker, P., Kulhanek, D. K., Holbourn, A., and Rosenthal, Y.: Accelerated mafic weathering in Southeast Asia linked to late Neogene cooling, Sci. Adv., 9, eadf3141, https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.adf3141, 2023.

Behar, F., Beaumont, V., and De B. Penteado, H. L.: Rock-Eval 6 Technology: Performances and Developments, Oil Gas Sci. Technol.-Rev. IFP, 56, 111–134, https://doi.org/10.2516/ogst:2001013, 2001.

Berends, C. J., de Boer, B., and van de Wal, R. S. W.: Reconstructing the evolution of ice sheets, sea level, and atmospheric CO2 during the past 3.6 million years, Clim. Past, 17, 361–377, https://doi.org/10.5194/cp-17-361-2021, 2021.

Berner, R. A.: The long-term carbon cycle, fossil fuels and atmospheric composition, Nature, 426, 323–326, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature02131, 2003.

Bertaz, J., Liu, Z., Colin, C., Dapoigny, A., Lin, A. T.-S., Li, Y., and Jian, Z.: Climatic and Environmental Impacts on the Sedimentation of the SW Taiwan Margin Since the Last Deglaciation: Geochemical and Mineralogical Investigations, Paleoceanogr. Paleocl., 39, e2023PA004745, https://doi.org/10.1029/2023PA004745, 2024.

Beusen, A. H. W., Bouwman, A. F., Van Beek, L. P. H., Mogollón, J. M., and Middelburg, J. J.: Global riverine N and P transport to ocean increased during the 20th century despite increased retention along the aquatic continuum, Biogeosciences, 13, 2441–2451, https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-13-2441-2016, 2016.

Boulay, S., Colin, C., Trentesaux, A., Frank, N., and Liu, Z.: Sediment sources and East Asian monsoon intensity over the last 450 ky. Mineralogical and geochemical investigations on South China Sea sediments, Palaeogeogr. Palaeocl., 228, 260–277, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.palaeo.2005.06.005, 2005.

Burke, K. D., Williams, J. W., Chandler, M. A., Haywood, A. M., Lunt, D. J., and Otto-Bliesner, B. L.: Pliocene and Eocene provide best analogs for near-future climates, P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 115, 13288–13293, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1809600115, 2018.

Canadell, J. G., Monteiro, P. M. S., Costa, M. H., Cotrim da Cunha, L., Cox, P. M., Eliseev, A. V., Henson, S., Ishii, M., Jaccard, S., Koven, C., Lohila, A., Patra, P. K., Piao, S., Rogelj, J., Syampungani, S., Zaehle, S., and Zickfeld, K.: 5 – Global Carbon and Other Biogeochemical Cycles and Feedbacks, in: Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, edited by: Masson-Delmotte, V., Zhai, P., Pirani, A., Connors, S. L., Péan, C., Berger, S., Caud, N., Chen, Y., Goldfarb, L., Gomis, M. I., Huang, M., Leitzell, K., Lonnoy, E., Matthews, J. B. R., Maycock, T. K., Waterfield, T., Yelekçi, O., Yu, R., and Zhou, B., Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA, 673–816, https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009157896.007, 2021.

Castelltort, S., Nagel, S., Mouthereau, F., Lin, A. T.-S., Wetzel, A., Kaus, B., Willett, S., Chiang, S.-P., and Chiu, W.-Y.: Sedimentology of early Pliocene sandstones in the south-western Taiwan foreland: Implications for basin physiography in the early stages of collision, J. Asian Earth Sci., 40, 52-71, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jseaes.2010.09.005, 2011.

Caves, J. K., Jost, A. B., Lau, K. V., and Maher, K.: Cenozoic carbon cycle imbalances and a variable weathering feedback, Earth Planet. Sc. Lett., 450, 152–163, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2016.06.035, 2016.

Chen, C.-W., Oguchi, T., Hayakawa, Y. S., Saito, H., Chen, H., Lin, G.-W., Wei, L.-W., and Chao, Y.-C.: Sediment yield during typhoon events in relation to landslides, rainfall, and catchment areas in Taiwan, Geomorphology, 303, 540–548, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geomorph.2017.11.007, 2018.

Chen, J.-M., Li, T., and Shih, C.-F.: Tropical cyclone- and monsoon-induced rainfall variability in Taiwan, J. Climate, 23, 4107–4120, https://doi.org/10.1175/2010jcli3355.1, 2010.

Chen, W.-S.: An Introduction to the Geology of Taiwan, Geologic Society of Taiwan, Taipei, Taiwan, 2016.

Cheng, X., Zhao, Q., Wang, J., Jian, Z., Xia, P., Huang, B., Fang, D., Xu, J., Zhou, Z., and Wang, P.: Data Report: Stable Isotopes from Sites 1147 and 1148, in: Proc. ODP, edited by: Prell, W. L., Wang, P., Blum, P., Rea, D. K., and Clemens, S. C., Sci. Results, 184, https://doi.org/10.2973/odp.proc.sr.184.223.2004, 2004.

Chien, F.-C. and Kuo, H.-C.: On the extreme rainfall of Typhoon Morakot (2009), J. Geophys. Res., 116, D05104, https://doi.org/10.1029/2010jd015092, 2011.

Chmura, G. L. and Aharon, P.: Stable carbon isotope signatures of sedimentary carbon in coastal wetlands as indicators of salinity regime, J. Coastal. Res., 11, 124–135, 1995.

Cleveland, W. S., Grosse, E., and Shyu, W. M.: Local Regression Models, in: Statistical Models in S, 1st edn., Routledge, New York, https://doi.org/10.1201/9780203738535, 1992.

Clift, P. D.: Controls on the erosion of Cenozoic Asia and the flux of clastic sediment to the ocean, Earth Planet. Sc. Lett., 241, 571–580, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2005.11.028, 2006.

Clift, P. D.: Variations in aridity across the Asia–Australia region during the Neogene and their impact on vegetation, Geol. Soc. Lond. Spec. Pub., 549, 157–178, https://doi.org/10.1144/SP549-2023-58, 2025.

Clift, P. D. and Jonell, T. N.: Himalayan-Tibetan Erosion Is Not the Cause of Neogene Global Cooling, Geophys. Res. Lett., 48, e2020GL087742, https://doi.org/10.1029/2020GL087742, 2021.

Clift, P. D., Wan, S., and Blusztajn, J.: Reconstructing chemical weathering, physical erosion and monsoon intensity since 25Ma in the northern South China Sea: A review of competing proxies, Earth-Sci. Rev., 130, 86–102, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earscirev.2014.01.002, 2014.

Clift, P. D., Jonell, T. N., Du, Y., and Bornholdt, T.: The impact of Himalayan-Tibetan erosion on silicate weathering and organic carbon burial, Chem. Geol., 656, 122106, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemgeo.2024.122106, 2024a.

Clift, P. D., Lee, J. I., Clark, M. K., and Blusztajn, J.: Erosional response of South China to arc rifting and monsoonal strengthening; a record from the South China Sea, Mar. Geol., 184, 207–226, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0025-3227(01)00301-2, 2002.

Clift, P. D., Du, Y., Mohtadi, M., Pahnke, K., Sutorius, M., and Böning, P.: The erosional and weathering response to arc–continent collision in New Guinea, J. Geol. Soc., 181, jgs2023-2207, https://doi.org/10.1144/jgs2023-207, 2024b.

Clift, P. D., Betzler, C., Clemens, S. C., Christensen, B., Eberli, G. P., France-Lanord, C., Gallagher, S., Holbourn, A., Kuhnt, W., Murray, R. W., Rosenthal, Y., Tada, R., and Wan, S.: A synthesis of monsoon exploration in the Asian marginal seas, Sci. Dril., 31, 1–29, https://doi.org/10.5194/sd-31-1-2022, 2022.

Covey, M.: The evolution of foreland basins to steady state: Evidence from the western Taiwan foreland basin, in: Foreland Basins, edited by: Allen, P. A. and Homewood, P., Blackwell Publishing Ltd., 77–90, https://doi.org/10.1002/9781444303810.ch4, 1986.

Dadson, S. J., Hovius, N., Chen, H., Dade, W. B., Lin, J.-C., Hsu, M.-L., Lin, C.-W., Horng, M.-J., Chen, T.-C., Milliman, J., and Stark, C. P.: Earthquake-triggered increase in sediment delivery from an active mountain belt, Geology, 32, https://doi.org/10.1130/g20639.1, 2004.

Dadson, S. J., Hovius, N., Chen, H., Dade, W. B., Hsieh, M.-L., Willett, S. D., Hu, J.-C., Horng, M.-J., Chen, M.-C., Stark, C. P., Lague, D., and Lin, J.-C.: Links between erosion, runoff variability and seismicity in the Taiwan orogen, Nature, 426, 648–651, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature02150, 2003.

Dagg, M., Benner, R., Lohrenz, S., and Lawrence, D.: Transformation of dissolved and particulate materials on continental shelves influenced by large rivers: plume processes, Cont. Shelf Res., 24, 833–858, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.csr.2004.02.003, 2004.

Dashtgard, S. E., Löwemark, L., Wang, P.-L., Setiaji, R. A., and Vaucher, R.: Geochemical evidence of tropical cyclone controls on shallow-marine sedimentation (Pliocene, Taiwan), Geology, 49, 566–570, https://doi.org/10.1130/g48586.1, 2021.

Dowsett, H. J.: The PRISM palaeoclimate reconstruction and Pliocene sea-surface temperature, in: Deep-Time Perspectives on Climate Change: Marrying the Signal from Computer Models and Biological Proxies, edited by: Williams, M., Haywood, A. M., Gregory, F. J., and Schmidt, D. N., Geological Society of London, Vol. 2, https://doi.org/10.1144/tms002.21, 2007.

Dürr, H. H., Meybeck, M., Hartmann, J., Laruelle, G. G., and Roubeix, V.: Global spatial distribution of natural riverine silica inputs to the coastal zone, Biogeosciences, 8, 597–620, https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-8-597-2011, 2011.

Espitalie, J., Deroo, G., and Marquis, F.: La pyrolyse Rock-Eval et ses applications. Première partie, Oil Gas Sci. Technol.-Rev. IFP, 40, 563–579, https://doi.org/10.2516/ogst:1985035, 1985.

Fedorov, A. V., Brierley, C. M., and Emanuel, K.: Tropical cyclones and permanent El Niño in the early Pliocene epoch, Nature, 463, 1066–1070, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature08831, 2010.

Fedorov, A. V., Brierley, C. M., Lawrence, K. T., Liu, Z., Dekens, P. S., and Ravelo, A. C.: Patterns and mechanisms of early Pliocene warmth, Nature, 496, 43–49, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature12003, 2013.

Froelich, P. N.: Kinetic control of dissolved phosphate in natural rivers and estuaries: A primer on the phosphate buffer mechanism, Limnol. Oceanogr., 33, 649–668, https://doi.org/10.4319/lo.1988.33.4part2.0649, 1988.

Galewsky, J., Stark, C. P., Dadson, S., Wu, C. C., Sobel, A. H., and Horng, M. J.: Tropical cyclone triggering of sediment discharge in Taiwan, J. Geophys. Res., 111, F03014, https://doi.org/10.1029/2005JF000428, 2006.

Galy, V., France-Lanord, C., Beyssac, O., Faure, P., Kudrass, H., and Palhol, F.: Efficient organic carbon burial in the Bengal fan sustained by the Himalayan erosional system, Nature, 450, 407–410, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature06273, 2007.

Ge, J., Torres, R., Chen, C., Liu, J., Xu, Y., Bellerby, R., Shen, F., Bruggeman, J., and Ding, P.: Influence of suspended sediment front on nutrients and phytoplankton dynamics off the Changjiang Estuary: A FVCOM-ERSEM coupled model experiment, J. Marine Syst., 204, 103292, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmarsys.2019.103292, 2020.

GEBCO Bathymetric Compilation Group: The GEBCO_2025 Grid – a continuous terrain model for oceans and land at 15 arc-second intervals, NERC EDS British Oceanographic Data Centre NOC [data set], https://doi.org/10.5285/37c52e96-24ea-67ce-e063-7086abc05f29, 2025.

Green, W. G. and Fearon, R. E.: Well logging by radioactivity, Geophysics, 5, 272–283, 1940.

Haq, B. U. and Ogg, J. G.: Retraversing the Highs and Lows of Cenozoic Sea Levels, GSA Today, 34, 4–11, https://doi.org/10.1130/GSATGG593A.1, 2024.

Haq, B. U., Hardenbol, J., and Vail, P. R.: Chronology of Fluctuating Sea Levels Since the Triassic, Science, 235, 1156–1167, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.235.4793.1156, 1987.

Hilton, R. G. and West, A. J.: Mountains, erosion and the carbon cycle, Nature Reviews Earth & Environment, 1, 284–299, https://doi.org/10.1038/s43017-020-0058-6, 2020.

Hilton, R. G., Galy, A., Hovius, N., Horng, M.-J., and Chen, H.: The isotopic composition of particulate organic carbon in mountain rivers of Taiwan, Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta, 74, 3164–3181, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gca.2010.03.004, 2010.

Hilton, R. G., Galy, A., Hovius, N., Horng, M.-J., and Chen, H.: Efficient transport of fossil organic carbon to the ocean by steep mountain rivers: An orogenic carbon sequestration mechanism, Geology, 39, 71–74, https://doi.org/10.1130/g31352.1, 2011.

Hoang, L. V., Clift, P. D., Schwab, A. M., Huuse, M., Nguyen, D. A., and Zhen, S.: Large-scale erosional response of SE Asia to monsoon evolution reconstructed from sedimentary records of the Song Hong-Yinggehai and Qiongdongnan basins, South China Sea, Geol. Soc. Lond. Spec. Pub., 342, 219–244, https://doi.org/10.1144/SP342.13, 2010.

Holbourn, A., Kuhnt, W., Clemens, S. C., and Heslop, D.: A ∼ 12 Myr Miocene record of East Asian Monsoon variability from the South China Sea, Paleoceanogr. Paleoclimatol., 36, https://doi.org/10.1029/2021pa004267, 2021.

Holbourn, A., Kuhnt, W., Schulz, M., and Erlenkeuser, H.: Impacts of orbital forcing and atmospheric carbon dioxide on Miocene ice-sheet expansion, Nature, 438, 483–487, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature04123, 2005.

Holbourn, A., Kuhnt, W., Schulz, M., Flores, J.-A., and Andersen, N.: Orbitally-paced climate evolution during the middle Miocene “Monterey” carbon-isotope excursion, Earth Planet. Sc. Lett., 261, 534–550, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2007.07.026, 2007.

Horng, C.-S.: Age of the Tananwan Formation in Northern Taiwan: A reexamination of the magnetostratigraphy and calcareous nannofossil biostratigraphy, Terr. Atmos. Ocean Sci., 25, 137–147, https://doi.org/10.3319/TAO.2013.11.05.01(TT), 2014.

Horng, C.-S. and Huh, C.-A.: Magnetic properties as tracers for source-to-sink dispersal of sediments: A case study in the Taiwan Strait, Earth Planet. Sci. Lett., 309, 141–152, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2011.07.002, 2011.

Hoshiba, Y. and Yamanaka, Y.: Along-coast shifts of plankton blooms driven by riverine inputs of nutrients and fresh water onto the coastal shelf: a model simulation, J. Oceanogr., 69, 753–767, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10872-013-0206-4, 2013.

Houghton, R. A.: Why are estimates of the terrestrial carbon balance so different?, Glob. Change Biol., 9, 500–509, https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2486.2003.00620.x, 2003.

Hsieh, A. I. J.: Organic carbon and nitrogen geochemistry of Taiwan and the northern South China Sea, Version v1, Zenodo [data set], https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.18397150, 2026.

Hsieh, A. I., Vaucher, R., Löwemark, L., Dashtgard, S. E., Horng, C. S., Lin, A. T.-S., and Zeeden, C.: Influence of a rapidly uplifting orogen on the preservation of climate oscillations, Paleoceanogr. Paleoclimatol., 38, e2022PA004586, https://doi.org/10.1029/2022PA004586, 2023a.

Hsieh, A. I., Dashtgard, S. E., Wang, P. L., Horng, C. S., Su, C. C., Lin, A. T., Vaucher, R., and Löwemark, L.: Multi-proxy evidence for rapidly shifting sediment sources to the Taiwan Western Foreland Basin at the Miocene–Pliocene transition, Basin Res., 35, 932–948, https://doi.org/10.1111/bre.12741, 2023b.

Hsieh, A. I., Dashtgard, S. E., Clift, P. D., Lo, L., Vaucher, R., and Löwemark, L.: Competing influence of the Taiwan orogen and East Asian Summer Monsoon on South China Sea paleoenvironmental proxy records, Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol., 635, 111933, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.palaeo.2023.111933, 2024.

Hsieh, A. I., Vaucher, R., MacEachern, J. A., Zeeden, C., Huang, C., Lin, A. T., Löwemark, L., and Dashtgard, S. E.: Resolving allogenic forcings on shallow-marine sedimentary archives of the Taiwan Western Foreland Basin, Sedimentology, 72, 1755–1785, https://doi.org/10.1111/sed.70020, 2025.

Hu, D., Böning, P., Köhler, C. M., Hillier, S., Pressling, N., Wan, S., Brumsack, H. J., and Clift, P. D.: Deep sea records of the continental weathering and erosion response to East Asian monsoon intensification since 14 ka in the South China Sea, Chem. Geol., 326–327, 1–18, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemgeo.2012.07.024, 2012.

Hu, J., Kawamura, H., Li, C., Hong, H., and Jiang, Y.: Review on current and seawater volume transport through the Taiwan Strait, J. Oceanogr., 66, 591–610, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10872-010-0049-1, 2010.

Hu, Z., Huang, B., Geng, L., and Wang, N.: Sediment provenance in the Northern South China Sea since the Late Miocene, Open Geosci., 14, 454, https://doi.org/10.1515/geo-2022-0454, 2022.

Huang, T.-H., Chen, C.-T. A., Bai, Y., and He, X.: Elevated primary productivity triggered by mixing in the quasi-cul-de-sac Taiwan Strait during the NE monsoon, Sci. Rep., 10, 7846, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-64580-6, 2020.

Jagoutz, O., Macdonald, F. A., and Royden, L.: Low-latitude arc–continent collision as a driver for global cooling, P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 113, 4935–4940, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1523667113, 2016.

Jakob, K. A., Wilson, P. A., Pross, J., Ezard, T. H. G., Fiebig, J., Repschläger, J., and Friedrich, O.: A new sea-level record for the Neogene/Quaternary boundary reveals transition to a more stable East Antarctic Ice Sheet, P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 117, 30980–30987, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2004209117, 2020.

Janapati, J., Seela, B. K., Lin, P.-L., Wang, P. K., and Kumar, U.: An assessment of tropical cyclones rainfall erosivity for Taiwan, Sci. Rep., 9, 15862, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-52028-5, 2019.

Jin, L., Shan, X., Vaucher, R., Qiao, S., Wang, C., Liu, S., Wang, H., Fang, X., Bai, Y., Zhu, A., and Shi, X.: Sea-level changes control coastal organic carbon burial in the East China Sea during the late MIS 3, Earth Planet. Sc. Lett., 229, 104225, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloplacha.2023.104225, 2023.

Kämpf, N. and Schwertmann, U.: Goethite and hematite in a climosequence in southern Brazil and their application in classification of kaolinitic soils, Geoderma, 29, 27–39, https://doi.org/10.1016/0016-7061(83)90028-9, 1983.

Kao, S.-J., Shiah, F.-K., Wang, C.-H., and Liu, K.-K.: Efficient trapping of organic carbon in sediments on the continental margin with high fluvial sediment input off southwestern Taiwan, Cont. Shelf Res., 26, 2520–2537, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.csr.2006.07.030, 2006.

Kao, S. J. and Milliman, J. D.: Water and sediment discharge from small mountainous rivers, Taiwan: The roles of lithology, episodic events, and human activities, J. Geol., 116, 431–448, https://doi.org/10.1086/590921, 2008.

Kissel, C., Liu, Z., Li, J., and Wandres, C.: Magnetic minerals in three Asian rivers draining into the South China Sea: Pearl, Red, and Mekong Rivers, Geochem. Geophy. Geosy., 17, 1678–1693, https://doi.org/10.1002/2016GC006283, 2016.

Kissel, C., Liu, Z., Li, J., and Wandres, C.: Magnetic signature of river sediments drained into the southern and eastern part of the South China Sea (Malay Peninsula, Sumatra, Borneo, Luzon and Taiwan), Sediment. Geol., 347, 10–20, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sedgeo.2016.11.007, 2017.

Krumins, V., Gehlen, M., Arndt, S., Van Cappellen, P., and Regnier, P.: Dissolved inorganic carbon and alkalinity fluxes from coastal marine sediments: model estimates for different shelf environments and sensitivity to global change, Biogeosciences, 10, 371–398, https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-10-371-2013, 2013.

Lee, T.-Y., Huang, J.-C., Lee, J.-Y., Jien, S.-H., Zehetner, F., and Kao, S.-J.: Magnified sediment export of small mountainous rivers in Taiwan: Chain reactions from increased rainfall intensity under global warming, PLoS One, 10, e0138283, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0138283, 2015.

Li, B., Wang, J., Huang, B., Li, Q., Jian, Z., Zhao, Q., Su, X., and Wang, P.: South China Sea surface water evolution over the last 12 Myr: A south-north comparison from Ocean Drilling Program Sites 1143 and 1146, Paleoceanography, 19, PA1009, https://doi.org/10.1029/2003PA000906, 2004.

Li, L., Li, Q., Tian, J., Wang, P., Wang, H., and Liu, Z.: A 4-Ma record of thermal evolution in the tropical western Pacific and its implications on climate change, Earth Planet. Sc. Lett., 309, 10–20, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2011.04.016, 2011.

Li, M., Wan, S., Colin, C., Jin, H., Zhao, D., Pei, W., Jiao, W., Tang, Y., Tan, Y., Shi, X., and Li, A.: Expansion of C4 plants in South China and evolution of East Asian monsoon since 35 Ma: Black carbon records in the northern South China Sea, Global Planet. Change, 223, 104079, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloplacha.2023.104079, 2023.

Li, X.-h., Wei, G., Shao, L., Liu, Y., Liang, X., Jian, Z., Sun, M., and Wang, P.: Geochemical and Nd isotopic variations in sediments of the South China Sea: a response to Cenozoic tectonism in SE Asia, Earth Planet. Sc. Lett., 211, 207–220, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0012-821X(03)00229-2, 2003.

Lin, A. T.-S. and Watts, A. B.: Origin of the West Taiwan basin by orogenic loading and flexure of a rifted continental margin, J. Geophys. Res.-Sol. Ea., 107, ETG 2-1–ETG 2-19, https://doi.org/10.1029/2001jb000669, 2002.

Lin, H.-T., Yang, J.-I., Wu, Y.-T., Shiau, Y.-J., Lo, L., and Yang, S.-H.: The spatiotemporal variations of marine nematode populations may serve as indicators of changes in marine ecosystems, Mar. Pollut. Bull., 211, 117373, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpolbul.2024.117373, 2025.

Lisiecki, L. E. and Raymo, M. E.: A Pliocene-Pleistocene stack of 57 globally distributed benthic δ18O records, Paleoceanography, 20, PA1003, https://doi.org/10.1029/2004pa001071, 2005.

Liu, J., Chen, Z., Chen, M., Yan, W., Xiang, R., and Tang, X.: Magnetic susceptibility variations and provenance of surface sediments in the South China Sea, Sediment. Geol., 230, 77–85, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sedgeo.2010.07.001, 2010a.

Liu, J. P., Liu, C. S., Xu, K. H., Milliman, J. D., Chiu, J. K., Kao, S. J., and Lin, S. W.: Flux and fate of small mountainous rivers derived sediments into the Taiwan Strait, Mar. Geol., 256, 65–76, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.margeo.2008.09.007, 2008.

Liu, J. P., Xue, Z., Ross, K., Wang, H. J., Yang, Z. S., Li, A. C., and Gao, S.: Fate of sediments delivered to the sea by Asian large rivers: Long-distance transport and formation of remote alongshore clinothems, The Sedimentary Record, 7, 4–9, https://doi.org/10.2110/sedred.2009.4.4, 2009a.

Liu, J. T., Hung, J.-J., Lin, H.-L., Huh, C.-A., Lee, C.-L., Hsu, R. T., Huang, Y.-W., and Chu, J. C.: From suspended particles to strata: The fate of terrestrial substances in the Gaoping (Kaoping) submarine canyon, J. Marine Syst., 76, 417–432, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmarsys.2008.01.010, 2009b.

Liu, J. T., Wang, Y.-H., Yang, R. J., Hsu, R. T., Kao, S.-J., Lin, H.-L., and Kuo, F. H.: Cyclone-induced hyperpycnal turbidity currents in a submarine canyon, J. Geophys. Res.-Oceans, 117, C04033, https://doi.org/10.1029/2011jc007630, 2012.

Liu, J. T., Kao, S. J., Huh, C. A., and Hung, C. C.: Gravity flows associated with flood events and carbon burial: Taiwan as instructional source area, Annu. Rev. Mar. Sci., 5, 47–68, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-marine-121211-172307, 2013.

Liu, Z., Alain, T., Clemens, S. C., and Wang, P.: Quaternary clay mineralogy in the northern South China Sea (ODP Site 1146), Sci. China Ser. D, 46, 1223–1235, https://doi.org/10.1360/02yd0107, 2003.

Liu, Z., Colin, C., Huang, W., Le, K. P., Tong, S., Chen, Z., and Trentesaux, A.: Climatic and tectonic controls on weathering in south China and Indochina Peninsula: Clay mineralogical and geochemical investigations from the Pearl, Red, and Mekong drainage basins, Geochem. Geophy. Geosy., 8, Q05005, https://doi.org/10.1029/2006gc001490, 2007.

Liu, Z., Zhao, Y., Colin, C., Siringan, F. P., and Wu, Q.: Chemical weathering in Luzon, Philippines from clay mineralogy and major-element geochemistry of river sediments, Appl. Geochem., 24, 2195–2205, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apgeochem.2009.09.025, 2009c.

Liu, Z., Colin, C., Li, X., Zhao, Y., Tuo, S., Chen, Z., Siringan, F. P., Liu, J. T., Huang, C.-Y., You, C.-F., and Huang, K.-F.: Clay mineral distribution in surface sediments of the northeastern South China Sea and surrounding fluvial drainage basins: Source and transport, Mar. Geol., 277, 48–60, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.margeo.2010.08.010, 2010b.