the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Holocene sea ice and paleoenvironment conditions in the Beaufort Sea (Canadian Arctic) reconstructed with lipid biomarkers

Madeleine Santos

Lisa Bröder

Matt O'Regan

Iván Hernández-Almeida

Tommaso Tesi

Lukas Bigler

Negar Haghipour

Daniel B. Nelson

Michael Fritz

The Beaufort Sea region in the Canadian Arctic has undergone substantial sea ice loss in recent decades, primarily driven by anthropogenic climate warming. To place these changes within the context of natural climate variability, Holocene sea ice evolution and environmental conditions (sea surface temperature, salinity, terrestrial input) were reconstructed using lipid biomarkers (HBIs including IP25, OH-GDGT, brGDGT, C16:0 fatty acid, phytosterols) from two marine sediment cores collected from the Beaufort Shelf and slope, spanning the past 9.1 ka and 13.3 cal. kyr BP, respectively. The Early Holocene (11.7–8.2 ka) is characterized by relatively higher sea surface temperature, lower salinity and no spring/summer sea ice until 8.5 ka on the Beaufort Sea slope. Around 8.5 ka, a peak in organic matter content is linked to both increased terrestrial input and primary production and may indicate increased riverine input from the Mackenzie River and terrestrial matter input from coastal erosion. Following this period, terrestrial inputs decreased throughout the Mid-Holocene in both cores. A gradual increase in IP25 and HBI-II concentrations aligns with relatively higher salinity, lower sea surface temperature and rising sea levels, and indicate the establishment of seasonal (spring) sea ice on the outer shelf around 7 ka and on the shelf around 5 ka. These patterns suggest an expansion of the sea ice cover beginning in the Mid-Holocene, influenced by decreasing summer insolation. During the Late Holocene (4.2–1 ka), permanent sea ice conditions are inferred on the slope with a peak during the Little Ice Age. After 1 ka, seasonal sea ice conditions on the slope are observed again, alongside an increase in salinity and terrestrial input, and variable primary productivity. Similar patterns of Holocene sea ice variability have been observed across other Arctic marginal seas, highlighting a consistent response to external climate forcing. Continued warming may drive the Beaufort Sea toward predominantly ice-free conditions, resembling those inferred for the Early Holocene.

- Article

(8095 KB) - Full-text XML

-

Supplement

(1977 KB) - BibTeX

- EndNote

Sea ice is a critical component of the Arctic climate system, influencing ocean–atmosphere interactions, modulating surface albedo (Kashiwase et al., 2017), regulating heat fluxes (Lake, 1967), and influencing ecosystem structure through its control on light penetration and nutrient cycling (Lannuzel et al., 2020). Its high sensitivity to temperature makes it both a driver and indicator of Arctic climate change. Since the late 1970s, satellite observations have revealed a significant decline in Arctic sea ice extent, sparking interest in the mechanisms that govern sea ice variability over multiple timescales (Stroeve et al., 2012). The Canadian Beaufort Sea is a marginal sea of the western Arctic Ocean which exhibits strong seasonal and interannual variability in sea ice cover. Characterized by landfast ice on the shelf and mobile pack ice offshore, this region has experienced significant sea-ice loss in recent decades due to rising atmospheric and oceanic temperatures (Carmack et al., 2015; Comiso et al., 2008).

Understanding natural variability of sea-ice prior to the industrial era is critical for contextualizing recent trends. Throughout the Holocene, Arctic sea ice has responded to changes in orbital forcing, ocean circulation, and ice sheet dynamics (Park et al., 2018; Stein et al., 2017). During the Late glacial, abrupt climatic events such as Bølling-Allerød (∼ 14–12.8 ka) and Younger Dryas (∼ 12.8–11.7 ka), contributed to the instability of the Arctic cryosphere. In the Canadian Arctic, enhanced meltwater discharge and re-routing following the retreat of the Laurentide Ice Sheet (LIS) contributed to oceanographic shifts and transient cooling events (Broecker et al., 1989). Lipid biomarker records and climate simulations from the Arctic suggest reduced sea ice during the Early Holocene thermal maximum (11–6 ka in the Canadian Arctic) (Kaufman et al., 2004), followed by expansion through the Middle to Late Holocene, consistent with declining summer insolation (Stranne et al., 2014; Wu et al., 2020a). Numerous studies on Arctic sea ice variability have focused on offshore locations highlighting heterogeneity in sea-ice cover history and the importance of local currents (Belt et al., 2010; Detlef et al., 2023; Fahl and Stein, 2012; Hörner et al., 2016, 2018; Stein et al., 2017; Stein and Fahl, 2012; Vare et al., 2009; Wu et al., 2020a). However, these studies often neglected the spatial extent of sea ice cover toward the coast and the migration of the marginal ice zone.

Sea-ice cover can be reconstructed from microfossil and lipid biomarker evidence preserved in marine sediments. Remains of sea-ice organisms such as dinocysts (de Vernal et al., 2013) and diatoms, the latter producing a specific biomarker known as IP25 (Belt et al., 2007), provide valuable records of past sea-ice conditions. This highly branched isoprenoid (HBI) and its isomer HBI diene (HBI-II) are used to trace the presence of spring sea-ice in modern and geological settings (e.g., Belt et al., 2010; Fahl and Stein, 2012; Hörner et al., 2016, 2018; Vare et al., 2009). However, because the absence of these two HBIs may reflect either a permanent sea-ice condition (due to the absence of light) or completely sea-ice free waters, the PIP25 ratio was developed (Müller et al., 2011). This ratio includes a phytoplankton biomarker (typically dinosterol, brassicasterol or HBI-III) that represents open-water productivity. PIP25 values have been used to distinguish between seasonal sea-ice (> 0.5) and permanent sea-ice cover (> 0.75).

Sea-ice cover is influenced by both the atmospheric and the oceanic forcing, including salinity and temperature, parameters that are often difficult to reconstruct in polar regions. Lipid biomarker and their (isotopic) ratios are a useful toolkit for this purpose. In particular, compound-specific hydrogen isotopes of phytoplankton biomarkers have shown promise for reconstructing past salinity (e.g., Lattaud et al., 2019; Sachs et al., 2018; Weiss et al., 2019). However, in the Arctic Ocean, the generally low abundances of lipid biomarker restrict this approach to the dominant lipid biomarkers, such as palmitic acid (C16:0 fatty acid; Sachs et al., 2018). In contrast to salinity, several established proxies exist for reconstructing seawater temperature, including microfossil assemblages (e.g., dinocyst; Richerol et al., 2008), inorganic ratios (e.g., Mg Ca of foraminifera; Barrientos et al., 2018; Kristjánsdóttir et al., 2007) and lipid biomarkers (Ruan et al., 2017; Varma et al., 2024). Among lipid biomarker proxies for cold water (< 15 °C) environments, hydroxylated glycerol dialkyl glycerol tetraether (OH-GDGT) are particularly useful, with RI-OH′ and TEX-OH identified as promising seawater temperature indices (Lü et al., 2015; Varma et al., 2024). Nevertheless, even the latest calibrations (Varma et al., 2024) reveal substantial uncertainty at low temperatures, partly due to the limited representation of polar core-top sediments, which are biased toward the European and Russian Arctic. These limitations highlight the need to further develop and test Arctic-specific proxies for both salinity and seawater temperature.

This study presents a multi-proxy reconstruction of Holocene sea ice and oceanographic variability from two sediment cores (PCB09, PCB11) collected from the Beaufort outer shelf and shelf slope. Lipid biomarkers, including highly branched isoprenoids (HBIs), glycerol dialkyl glycerol tetraethers (GDGTs), the hydrogen isotopic compositions of algal-derived fatty acids and terrestrial sterols, are used to reconstruct sea-ice cover, sea surface temperatures (SSTs), salinity and terrestrial organic matter input. Additionally, a set of surface sediments is used to assess the applicability and calibrate salinity and SST proxies in sediments of the Beaufort Sea.

The primary objectives are to (1) reconstruct past variations in sea-ice cover on the Beaufort Shelf throughout the Holocene, (2) explore the potential roles of insolation changes, meltwater input, and oceanic conditions in shaping regional sea-ice variability, and (3) place the Beaufort Sea record within a broader Arctic context to provide insights into past and present climate variability.

2.1 Study area

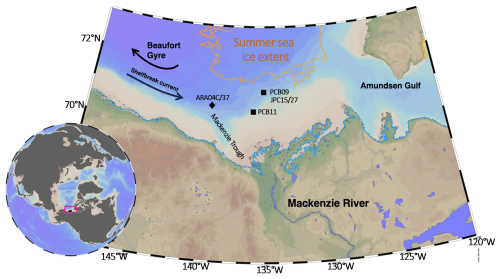

The study focuses on the Canadian Beaufort Sea, one of the marginal seas of the Arctic Ocean (Fig. 1), bounded by the glacially excavated Amundsen Gulf to the east, Mackenzie Trough to the west, and the Mackenzie River delta to the south (Carmack et al., 2004). The shelf is a large estuarine setting at the interface between the Arctic Ocean and the Mackenzie River (Omstedt et al., 1994) (Fig. 1). The Mackenzie River is a significant source of freshwater to the Beaufort Sea, with an annual water discharge of 316 km3 yr−1 (Holmes et al., 2012) and is considered the largest Arctic river in terms of sediment flux (124–128 Mt yr−1) (Stein et al., 2004). At the same time, permafrost coastal erosion adds another 8–9 Mt yr−1 of sediment into the Beaufort Sea, including carbon and nutrients (Wegner et al., 2015). Surface water circulation in the Beaufort Sea is primarily characterized by the clockwise Beaufort Gyre, which drives offshore currents towards the west and traps the majority of the Arctic Ocean's freshwater in the Canada Basin (Serreze et al., 2006). There is also a eastward flowing shelf-break current at depths beneath 50 m, which transports Pacific Water (coming from the Bering Strait) along the slope (Pickart, 2004). Sea ice cover on the Beaufort Shelf north of the Mackenzie River Delta varies from year to year, but generally begins to form in mid-October, persisting until ice break up in April–May (Fig. S1 in the Supplement). During ice break up, an open water flaw lead occurs along the outer edge of the landfast ice establishing a spring marginal ice zone over the shelf.

Figure 1Combined topographic and bathymetric map of the Beaufort Shelf region (Canadian Arctic) displaying the cores from this study as black squares (PCB09 and PCB11) and key records discussed in the text (ARA04C/37 from Wu et al., 2020a; JPC15/27 from Keigwin et al., 2018). The 2021 summer sea-ice extent is outlined by the orange dotted line, the winter sea ice extent follows the coastline (Meier et al., 2018). Map generated using Ocean Data View (Schlitzer, 2025).

2.2 Material

Two sediment cores were analyzed in the study. They were recovered as part of the Permafrost Carbon on the Beaufort Shelf (PeCaBeau) project during the 4th Leg of the 2021 CCGS Amundsen expedition (Bröder et al., 2022, Fig. 1). At station PCB09 (71.1° N, 135.1° W) at a water depth of 675 m on the Beaufort shelf slope, a piston core (PC, length of 420 cm) and multicore (MC, 30 cm) were retrieved (Fig. 1). At station PCB11 (70.6° N, 136.0° W) on the outer Beaufort shelf (74 m water depth) a giant gravity core (GGC, length of 290 cm) and MC (32 cm) were recovered (Fig. 1). PCB09 is found within the modern Atlantic bottom water mass, while PCB11 lies within the Pacific summer water (Fig. S2), the water masses were defined as in Matsuoka et al. (2012). The core tops (0–1 cm) from 22 multicores collected during PeCaBeau, were used to ground truth the hydrogen isotope ratio of C16:0 fatty acid proxy for reconstructing salinity and test the applicability of the SST reconstructions (Fig. S1).

2.3 Methods

2.3.1 Core processing

During the PeCaBeau expedition, all cores were scanned shipboard on a Geotek multi-sensor core logger (MSCL). Bulk density and magnetic susceptibility were measured at a 1 cm downcore resolution on the piston and gravity cores, (Bröder et al., 2022). The cores remained unopened and were shipped to AWI Potsdam following the expedition. They were subsequently split in the fall/winter and the working halves sampled using 2 × 2 cm u-channels, before being cut into 1–2 cm thick slices which were frozen and freeze dried.

An ITRAX XRF-core scanner was used to measure relative elemental abundances at Stockholm University, Sweden. Measurements were performed on u-channel samples at a downcore resolution of 2 mm. Analyses were made using a Mo tube at a voltage of 55 kV, a current of 50 mA and an exposure time of 20 s. Here we present the ratios of Ca Ti, reflecting detrital carbon inputs regionally elevated by meltwater delivery from either the Mackenzie or Amundsen Gulf during deglaciation (Klotsko et al., 2019; Swärd et al., 2022; Wu et al., 2020a). Zr Rb was used as a proxy for grain size variations as Zr content is elevated in coarse minerals, while Rb is associated with clay minerals (Wu et al., 2020b) and Br Cl as a proxy for marine organic matter as Br usually correlates well with OC content (Wang et al., 2019).

2.3.2 Age model

The chronology of the piston and gravity cores (Fig. 2) were determined by 14C dating of foraminifera (n = 13, PCB09) and bivalve shells (n = 7, PCB11) (Table S1). The MSCL data was used to stratigraphically correlate PCB09 with JPC15/27 (Keigwin et al., 2018) allowing us to integrate existing radiocarbon ages (n = 8) from this record with our new data (n = 5) (Fig. S3).

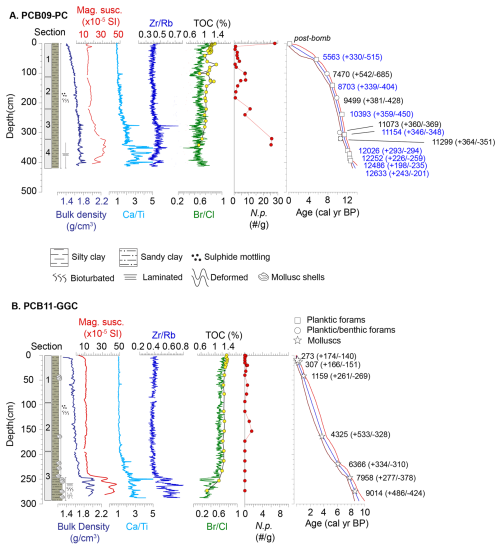

Figure 2Core description for (A) PCB09 and (B) PCB11 presenting lithostratigraphy, bulk density, magnetic susceptibility, X-Ray Fluorescence (XRF) results including Ca Ti, Zr Rb and Br Cl ratios. Total organic carbon content (%) and abundance of N. pachyderma (N. p., number per gram of sediment) as well as the age models of PCB09 and PCB11 generated using the Bacon Rpackage (Blaauw and Christen, 2011). The red bands illustrate the 95 % confidence level around the modelled median age (blue line). Symbols indicate the calibrated age of the dated material before age-modelling. The errors on these are lower than the symbol size. The numbers are the median modelled ages and 95 % error at the location of each sample. Blue radiocarbon ages originated from nearby core HLY13-15JPC (Keigwin et al., 2018).

Bivalve shells were either picked from the split cores when sampling, or later from the freeze-dried sediments. Foraminifera were picked from the > 45 µm fraction of the wet-sieved samples following organic extractions. Foraminifera samples consisted of either planktonic (Neogloboquadrina pachyderma), benthic, or a combination of both in horizons when specimens were extremely rare. Care was given to pick well preserved foraminifera to avoid age bias (Wollenburg et al., 2023). Foraminifera and mollusk samples were prepared for Accelerator Mass Spectrometry (AMS) analyses at the Laboratory for Ion Beam Physics at ETHZ using procedures described in Missiaen et al. (2020) which include sieving and acid cleaning to remove impurities from the shells.

Radiocarbon-based age models were generated using the BACON package in R (Blaauw and Christen, 2011) and the Marine20 calibration curve (Heaton et al., 2020). A reservoir age of 330 ± 41 years was applied to the Holocene-age mollusc samples in PCB11 as determined by West et al. (2022) for Pacific waters entering the Arctic Ocean in the Chukchi Sea. For PCB09 we applied the approach used for JPC15/27 (Keigwin et al., 2018) and for ARA04C/37 (Wu et al., 2020a) but updated for Marine20 as described by Lin et al. (2025). A reservoir correction of −150 ± 100 years was applied to Holocene planktic foraminifera, and a larger reservoir correction (50 ± 100 years) for the bottom 4 samples (Table S1) that fall within the Younger Dryas. In our age model we also incorporate samples of benthic foraminifera that were calibrated using a reservoir correction of 206 ± 67 years, determined by West et al. (2022) for Atlantic waters near the Chukchi Sea. Samples containing mixed planktic and benthic foraminifera were calibrated using an average of these values (28 ± 85 years).

2.3.3 Bulk organic matter

For the determination of total organic carbon (TOC) content and stable carbon isotope composition (δ13C) at the University of Basel, about 12 mg of freeze-dried sediment was weighed into each silver capsule and 1–2 drops of distilled water were added. The samples were exposed to fuming hydrochloric acid (HCl, 37 %) in a desiccator for 24 h to remove inorganic carbon. Samples were dried (48 h, 50 °C) and analyzed using an elemental analyser coupled to an isotope mass spectrometer (Sercon, Integra 2). The standards used to calculate TOC was Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA, Sigma Aldrich) and for δ13C were USGS40 (−26.389 ± 0.042 ‰, IAEA), USGS64 (−40.81 ± 0.04, IAEA), and USGS65 (−20.29 ± 0.04, IAEA). The analytical precision, defined as the standard deviation of the measurement of the USGS standards for the δ13C sequence was ±0.03 ‰.

2.3.4 Lipid biomarkers

Lipid biomarkers were analysed from 42 samples (every 10 cm for the first 143 cm, then every 20 cm) for PCB09 and 21 for PCB11 (every 20 cm). Core top samples from the MC's were also analysed for lipid biomarkers. For each sample, 5 g of homogenized freeze-dried sediment was extracted using an Energy Dispersive Guided Extraction (EDGE) following (Lattaud et al., 2021a). Briefly, after extraction with dichloromethane (DCM) : methanol (MeOH) (9 : 1, ), the total lipid extracts (TLE) were saponified at 70 °C for 2 h (with KOH in MeOH at 0.5 M). The neutral phase was collected by liquid-liquid extraction with 10 mL of hexane, three times. The leftover TLE was acidified to pH 2 and the acid phase was recovered by liquid-liquid extraction adding 10 mL hexane : DCM (4 : 1, ), three times. The acid compounds were methylated by adding MeOH : HCl (95 : 5, ) and heated at 70 °C overnight. The methylated fatty acids were recovered by liquid-liquid extraction (three times) with 10 mL hexane : DCM (4 : 1, ). Internal standards were added to the neutral fraction prior to silica chromatography: 7-hexylnonadecane (7-HND, provided by Simon Belt), 9-octylheptadec-8-ene (9-OHD, provided by Simon Belt), C22 5,16-diol (Interbioscreen), C36:0 alkane (Sigma Aldrich) and C46 GDGT-like compound (C46 glycerol trialkyl glycerol tetraether, GTGT; Huguet et al., 2006). The neutral phase was separated into three fractions (F1, F2, and F3) through silica column (combusted and deactivated 1 %) using hexane : DCM (9 : 1, ), DCM, and DCM : MeOH (1 : 1, ), respectively.

The F1 containing HBIs was analyzed on a GC-MS (Agilent 7890-5977A) operating in Selective Ion Monitoring (SIM) mode at the Institute of Polar Sciences (ISP), Bologna, Italy, following (Belt et al., 2014). The column used was a J&W DB5-MS (length 30 m, id 250 µm, 0.25 µm thickness). Integrations were done in SIM mode for IP25 ( = 350), HBI II ( = 348) and HBI III and HBI IV ( = 346). Concentrations of IP25 were corrected for 348 influence (4 %) and instrumental response factor. 9-OHD ( 350) was used to quantify HBIs. A reference sediment containing known amount of IP25 was run in parallel to correct IP25 concentration.

F3 was split in two with one aliquot that was filtered using a polytetrafluoroethylene filter (PTFE, 0.45 µm pore size) and analyzed for GDGTs with high performance liquid chromatography (LC)/atmospheric pressure chemical ionization–MS on an Agilent 1260 Infinity series LC-MS according to Hopmans et al. (2016) with the adaptation of Lattaud et al. (2021b). GDGTs were quantified using the C46 GTGT internal standard assuming the same response factor.

The other F3 aliquot was silylated with bis(trimethylsilyl)trifluoroacetamid (BSTFA) (70 °C 30 min) and analysed at the ISP for sterol concentration (brassicasterol, stigmasterol, β-sitosterol, campesterol) on a GC-MS. The C22 5,16-diol is used to quantify sterols. Specific ratios have been extracted from chromatograms in order to identify each biomarker according to their respective mass spectra, sterols were quantified on the total ion current.

Lipid δ2H values were analyzed by GC coupled to an isotope ratio mass spectrometer (IRMS) on all acid fractions having adequate compound abundance. Samples were analyzed using splitless injection with a split/splitless inlet at 280 °C and a Restek Rtx-5MS GC column (30 m × 0.25 mm × 0.25 µm) with helium carrier gas at 1.4 mL min−1. The GC oven was held at 60 °C for 1.5 min, ramped to 140 °C at 15 °C min−1, then to 325 °C at 4 °C min−1, and held for 15 min. Column effluent was pyrolyzed at 1420 °C, and δ2H values were measured on a Thermo Delta V Plus IRMS. The H factor was evaluated with each measurement sequence to confirm stability. Values were always lower than 3 ppm mV−1. Reference standards with known isotopic compositions (Mix A7, USGS71, C30:0 FAME; provided by Arndt Schimmelmann, Indiana University, USA) were analyzed alongside samples to normalize values to the Vienna Standard Mean Ocean Water-Standard Light Antarctic Precipitation (VSMOW-SLAP) scale. Standards were injected at a range of concentrations so that peak size effects could be assessed and corrected for. Quality control samples with known δ 2H values were measured as unknowns to check precision and accuracy (C16:0 FAME in mix F8-40, C30:0 FAME; Arndt Shimmelmann), which were 4.2 ‰ or better, and 1.0 ‰ or better, respectively (n = 13–16). Final fatty acid δ2H values of C16:0 were corrected for added hydrogen during methylation following Eq. (1).

Where nH = 3, nHFAME=32.

2.3.5 Biomarker ratios and environmental indicator reconstructions (sea ice, salinity, SSTs)

In order to describe sea ice variability in the Holocene, the PIP25 index is used (Müller et al., 2011). The PIP25 index (Eq. 2) uses additional phytoplankton biomarkers (i.e. brassicasterol, dinosterol, and HBI-III) which indicate open water conditions to compare with the abundance of IP25 (Belt et al., 2007):

HBI-III was used in this study (Belt et al., 2015; Kolling et al., 2020; Köseoğlu et al., 2018; Smik et al., 2016) as a reference for pelagic phytoplankton to derive PIIIIP25 index (afterward called PIP25). Dinosterol was not detected in the samples which is common in the Beaufort Sea (Fu et al., 2025), and brassicasterol has been shown to derive mainly from terrestrial input in the region (Wu et al., 2020a). The c value represents the ratio of the mean concentration of IP25 over the mean concentration of HBI-III of all samples for each core (4.79 for PCB09 and 5.55 for PCB11).

Surface salinity was reconstructed using the calibration between δ2H of C16:0 fatty acid (palmitic acid) and salinity from the test study of Sachs et al. (2018) (Eq. 3), adding data from Allan et al. (2023) and after testing surface sediments from multicores from the region (Fig. S4):

where S is salinity in practical salinity units (psu). Based on the known calibration errors (4 ‰ for the δ2H measurement), reconstructed salinity should have an associated error of ±7 psu.

To reconstruct SST, hydroxylated GDGTs (OH-GDGTs) were used as the hydroxyl group in these GDGTs is suggested to be an adaptation feature to regulate permeability in cold waters (Liu et al., 2012). In this study, the RI-OH′ (Eq. 4) and TEX-OH (Eq. 5) indexes were calculated:

For the conversion from RI-OH′ and TEX-OH to SST, the recent calibration of Varma et al. (2024) is used (Eqs. 6 and 7):

Several organic proxies have been used to interpret terrestrial organic matter input such as branched glycerol dialkyl glycerol tetraether (brGDGTs), long chain n-alkanes, and plant sterols. BrGDGTs are membrane lipids synthesized by bacteria and are known to be ubiquitous in terrestrial environments (Schouten et al., 2013). The BIT index (Hopmans et al., 2004) (Eq. 8) is a common indicator of terrestrial input into the marine realm:

In addition, in situ marine production of brGDGT can occur in coastal sediments between 50 and 300 m water depth (Peterse et al., 2009; Sinninghe Damsté, 2016). To assess the potential for brGDGT to be produced in situ we calculated the number of cyclopentane rings present in the tetraether brGDGT (#ringtetra) (Eq. 9):

2.3.6 Micropaleontology

Extracted sediments were wet sieved using a 45 µm mesh. The > 45 µm fraction was dried in the oven (40 °C) and picked for foraminifera using a stereoscopic microscope. Planktonic foraminifera species are identified (https://www.mikrotax.org/pforams/, last access: 1 August 2023) using the morphological descriptions compiled in Microtax and counted for each sample.

3.1 Core chronology, lithostratigraphy and bulk organic matter

The age models of cores PCB09 (Fig. 2a) and PCB11 (Fig. 2b) show that they cover the last 13350 ± 690 and 9120 ± 720 cal. yr BP, respectively. PCB11 had a mean sedimentation rate of 35 ± 10 cm kyr−1 with slightly higher sedimentation rates in the Late Holocene (< 4 ka). Conversely, PCB09 had an average sedimentation rate of 50 ± 27 cm kyr−1, with substantially higher sedimentation rates before the Late Holocene.

The upper 300 cm of PCB09 (0–11 ka) display a gradual downcore increase in bulk density, reflecting porosity loss in largely homogenous silty-clay sediments (Fig. 2a). Below 300 cm, slightly higher variability in the bulk density, elevated magnetic susceptibility and higher Zr Rb all point towards a transition to slightly coarser-grained sediments. Ca Ti tended to increase downcore becoming more variable below 105 cm (7.6 ± 0.6 cal yr BP). There was a notable stepwise increase in Ca Ti at 345 cm (11.7 ± 0.4 ka, Fig. 2a). Discrete peaks in Zr Rb and bulk density, indicative of sediment coarsening, co-occurred with elevated Ca Ti ratios at depths of 276 cm (10.8 ± 0.4 cal. yr BP), 345–352 cm (11.8 ± 0.4 cal. yr BP) and 402 cm (12.8 ± 0.4 cal. yr BP).

A similar pattern is seen in PCB11, where below 240 cm (7.4 ± 0.6 cal. yr BP) there was an abrupt increase in bulk density, magnetic susceptibility, Zr Rb and Ca Ti. TOC concentrations and the Br Cl ratio (which mirrors small scale changes in the TOC) also decreased notably through this interval (Figs. 2b, 3a). This lithologic transition post-dates the Late glacial and Early Holocene detrital carbonate inputs in cores recovered from the Beaufort Sea slope (Klotsko et al., 2019). It is likely that this coarser basal facies is related to the inundation of the shelf during transgression.

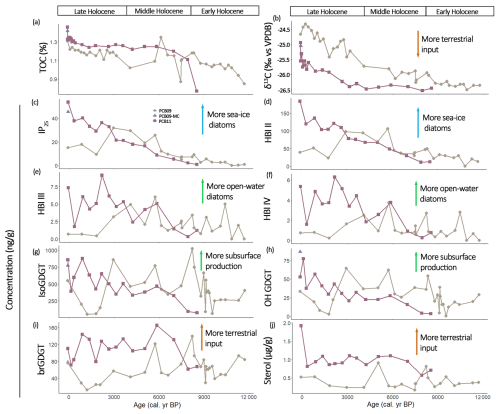

Figure 3Bulk characteristics and biomarker concentrations (in ng g) for core PCB09 (brown circles) and PCB11 (red squares) with (a) total Organic Carbon (TOC), (b) δ13C, (c) IP25, (d) HBI-II, (e) HBI III, (f) HBI IV, (g) isoprenoid GDGTs (isoGDGT), (h) hydroxylated GDGTs (OH-GDGT), (i) branched GDGTs (brGDGT) and (j) terrestrial sterols (sum of brassicasterol, stigmasterol, β-sitosterol, campesterol).

Bulk sediment δ13C of PCB09 was lowest in the Early Holocene at approximately −26.3 ‰ until 8.7 ± 0.4 ka, before increasing during the Middle and Late Holocene to −24.7 ‰ (Fig. 3b). The trend in δ13C in PCB11 is similar to PCB09 showing a steady increase over time from −26.5 ‰ to −25.8 ‰.

3.2 Lipid biomarkers

IP25 and HBI II (C25:2) concentrations were generally low (< 2 ng g−1) in the Early Holocene (Fig. 3c, d). IP25 in both cores increased throughout the Middle to Late Holocene. During the Late Holocene, IP25 and HBI II concentrations dropped in PCB09 around 1.8 ± 1.5 ka. Concentrations of both biomarkers were higher in PCB11 than in PCB09 after 3 ka, reaching modern values of 40 and 150 ng g−1 (IP25 and HBI II). PIP25 values in both cores increased from the Early to the Mid-Holocene (Fig. 4a).

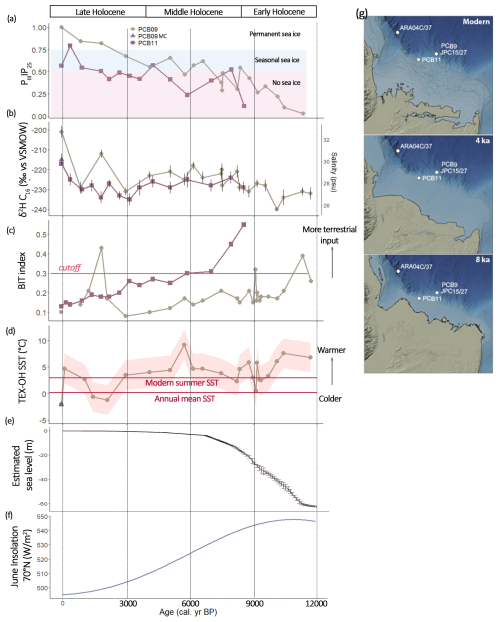

Figure 4Reconstructed environmental parameters for PCB09 (brown circles) and PCB11 (red squares) (a) PIIIIP25 (PIP25 calculated with HBI III as phytoplankton biomarker), (b) δ2H of C16:0 fatty acid and corresponding reconstructed salinity (Sachs et al., 2018), (c) BIT index (Hopmans et al., 2004), (d) SST derived from TEX-OH (Varma et al., 2024) shaded areas indicate the uncertainties of the reconstruction, modern (1995–2004) annual and summer SSTs were extracted from (Locarnini et al., 2024) (e), global sea level estimates derived from Lambeck et al. (2014) and (f) 21 June insolation at 70° N (Laskar et al., 2004). (g) Illustrative examples of plaeoshorelines at 8 and 4 ka compared to the modern. These were generated by adjusting the sea-level using the modern bathymetry portrayed in IBCAO V. 5 (Jakobsson et al., 2024). Relative sea-level adjustments were taken from ICE 6G_C (Peltier et al., 2015) for the grid cell encompassing the position of PCB11. The sea-level adjustments for this location were 46 m at 8 ka and 12 m at 4 ka (Fig. S7).

HBI III (C25:3) and HBI IV (C25:4) were low in both cores with values below 8 ng g−1 (Fig. 3e, f). Concentrations were higher in PCB11 than in PCB09 after 4 ka.

The concentration of isoGDGTs and OH-GDGTs followed a similar pattern throughout the Holocene (Fig. 3g, h). IsoGDGTs and OH-GDGT concentrations in PCB09 were stable during the Early Holocene at around 400 and 25 ng g−1, respectively. At around 8.5 ka, the isoGDGTs and OH-GDGT amounts doubled. Throughout the Mid-Holocene, isoGDGTs and OH-GDGT concentrations were variable but above 500 ng g−1. A drop in PCB09 to almost below detection limits occurred between 1–1.5 ka. IsoGDGTs and OH-GDGTs in PCB11 showed a steady increase from around 100 and 10 ng g−1, respectively, in the Early Holocene to > 500 and > 50 ng g−1 (Fig. 3g, h).

BrGDGTs concentrations in PCB09 were below 100 ng g−1 throughout the cores except for peaks during the Early and Mid-Holocene at 11.2 ± 0.3, 8.2 ± 0.5 and 5.7 ± 0.5 ka, the latter was also seen in PCB11 (albeit concentrations were higher in PCB11) (Fig. 3i). BIT values varied from 0.1 to 0.4 in PCB09 and from 0.1 and 0.5 in PCB11. The #ringtetra values were always < 0.7 for both cores. Terrestrial sterol concentrations in PCB09 were relatively stable throughout the core except for short-lived peaks at 9.5 ± 0.4, 8.2 ± 0.5 and 5.0 ± 0.9 ka (Fig. 3j). In PCB11, the concentration remained stable throughout the core after an initial increase at 6.9 ± 0.6 ka and a peak in the surface sediment.

Although biomarker concentrations expressed per gram of sediment may be influenced by mineral dilution or post-depositional degradation, TOC contents in our cores varied only slightly (0.9 %–1.3 % in PCB09 and 1.1 %–1.3 % in PCB11; Fig. 3a). Such limited variability indicates that TOC normalization would not substantially alter the observed trends. The distinct downcore patterns among lipid biomarker classes therefore likely reflect differences in source input and preservation rather than a uniform effect of degradation or dilution.

3.3 Salinity, SST and terrestrial input inferred from biomarker ratios

Surface sediments δ2H C16:0 values from the Beaufort Sea (Figs. S1, S4) range from −275 ‰ to −200 ‰, comparable with the values obtained by the preliminary study of Sachs et al. (2018). δ2H C16:0 values of all sediments correlate with summer salinity (r2 = 0.63, p < 0.001) and the calibration equation is the same as the one obtained by Sachs et al. (2018). It is to be noted that the uncertainty associated with the analysis and calibration reaches 7 psu, which is quite large for salinity changes over glacial-deglacial timescales. This is to the contrary to what Allan et al. (2023) and Wu et al. (2025) observed in a set of surface sediments in Baffin Bay and a downcore record of the Beaufort Sea, where no relationship with salinity is observed. This contrast for the surface sediments could come from the different environment as Baffin Bay is a much more enclosed basin compared to the Beaufort Sea, or that δ2H C16:0 values encompassed a too small range of salinity (28–34 psu). The downcore Beaufort Sea record yielded no notable salinity response of the δ2H C16:0 when large freshwater influence were expected, which was attributed to the production of C16:0 by heterotrophs (Wu et al., 2025).

Sea surface salinity inferred from δ2H C16:0 values at PCB09 increased from 27 ± 7 psu during the Early Holocene to 30 ± 7 psu during the Mid-Holocene, and remained stable until 3 ka, increasing to 32 ± 7 psu during the Late Holocene (Fig. 4b). Reconstructed salinity at PCB11 was more stable during the Mid-Holocene and Late Holocene (28 ± 7 psu) until an increase to 30 ± 7 psu in the last centuries. (Fig. 4b). Although uncertainties associated with reconstructed salinity are large (±7 psu) the salinity trend between both locations agree with modern observations of lower salinities at PCB11 than further offshore at PCB09 (Fig. S2).

Two different sets of SSTs were reconstructed using the OH-GDGT only (RI-OH′) or a combination of OH- and isoGDGT (TEX-OH) (Figs. 4d, S4, S5a, b). SSTs were only reconstructed when the BIT index was below 0.3 (Fig. 4c) as both calibrations are sensitive to terrestrial input (Varma et al., 2025). RI-OH′ in the surface sediments varies from 0.05 to 0.17 while TEX-OH varies from 0.08 to 0.32. Both indexes plot in the global calibration curves from (Varma et al., 2024) and the reconstructed SST varies from 0.9 to 4.0 and −0.1 to 11.6 °C, respectively. TEX-OH reconstructed SSTs in PCB09 varied between 7 ± 2.6 °C in the Early Holocene, remained stable during the Mid-Holocene (∼ 3 ± 2.6 °C), decreased to 0 ± 2.6 °C between 1–1.5 ka and after which they increase to 5 ± 2.6 °C, close to modern summer SST (Locarnini et al., 2024). The reconstructed SST in the multicore is −1 ± 2.6 °C, similar, within the calibration error, to modern annual SST (Locarnini et al., 2024) (Fig. 4d). RI-OH′ reconstructed SSTs in PCB09 produce high temperatures (∼ 12 ± 2.6 °C) between 7 and 10 ka, maybe due to non-thermal impact on the production of OH-GDGT (Harning and Sepúlveda, 2024). For both cores, reconstructed SST using RI-OH′ is stable around 3 °C (Fig. S5b). PCB11 TEX-OH reconstructed SSTs are stable during the Early to Mid-Holocene (∼ 5.0 ± 2.6 °C). However, after 1 ka the reconstruction produces unrealistically large variation (5–15 °C, Fig. S5a).

The BIT index showed a steady decrease in PCB11 throughout the Holocene and until 3 ka in PCB09 (Fig. 4c). In PCB09, this decrease was interrupted at 9 and at 1.5 ka with BIT index values reaching 0.3 and 0.4, respectively. The increase at 9 ka was likely due to a relative decrease in crenarchaeol concentration (Fig. S5a) whereas the 1.5 ka increase was likely due to a decrease in brGDGT concentration (Fig. 4i).

3.4 Micropaleontology

Almost all of the planktonic foraminifera (99 %–100 % in abundance relative to other species) observed in PCB09 are N. pachyderma, formerly N. pachyderma sinistra. This is expected since this species has been found to dominate polar water masses (e.g. Eynaud 2011; Moller, Schulz, and Kucera 2013). Planktonic foraminifera are mostly absent in PCB11, consistent with data from plankton tows indicating that planktic foraminifera are rare on the Canadian shelf where surface waters are influenced by Mackenzie River discharge (Vilks, 1989). In PCB09, the foraminiferal shells appear white and fragmented in sections with abundant light-colored and sand-sized ice-rafted debris and other detrital materials (Fig. S6). Foraminifera are more abundant in samples that have relatively more mud aggregates than sand-sized debris (Fig. 2a, b). There is almost zero accumulation rate (per mm yr−1) of N. pachyderma within the shelf slope from 10 ka.

This study aims to reconstruct Holocene paleoenvironmental conditions in the southeastern Beaufort Sea focusing on spatial variability between the shelf slope (> 500 m water depth) and the outer shelf (< 100 m water depth). By analyzing the abundance and ratios of sea ice biomarkers (IP25, HBI II), phytoplankton and heterotrophic archaeal productivity markers (HBI III, HBI IV, iso- and OH-GDGT), terrestrial inputs (brGDGTs, terrestrial sterols), and reconstructed environmental indicators (salinity, SST) this study aim to highlight spatial environmental difference between a shallow (PCB11) and deep (PCB09) site. In the following sections, we interpret biomarker records in a chronological framework, highlighting the dynamic relationship between freshwater inputs, ocean circulation, and sea ice conditions.

4.1 Late glacial to Early Holocene (12–8.2 ka)

The Late glacial to Early Holocene is only recorded at the shelf slope location (PCB09, Fig. 1). This period is characterized by low concentrations of sea ice biomarkers (Fig. 3a, b) resulting in low PIP25 values (Fig. 4a). The low concentration suggests that this area had intermittent sea ice coverage during the Late glacial to Early Holocene, but the presence of HBI III and HBI IV (Fig. 3e, f) indicate that the region was only under seasonal ice cover until spring allowing late spring/summer open-water diatom primary production (Belt et al., 2015). Heterotrophic production in the shelf slope region during this period is relatively low (as suggested by the presence of ammonium oxidizer Thaumarchaea-derived isoGDGTs; Schouten et al., 2013; Fig. 3g, h) but increased and peaked at 8.2 ± 0.5 ka. During 12–8.2 ka, SSTs were elevated in comparison with the rest of the Holocene (Fig. 4d) which coincided with peak 21 June insolation (Fig. 4f) (Clemens et al., 2010; Laskar et al., 2004). The warmer surface waters might have inhibited the development of sea ice over the Beaufort Shelf.

During the Late glacial to Early Holocene, large freshwater inputs to the Beaufort Shelf, inferred from the low reconstructed salinity (Fig. 4b) likely originated from the decaying Laurentide Ice Sheet. Such water masses derived from drainage regions that had undergone minimal weathering would have released low amounts of nutrients. The influx of low-salinity freshwater may have intensified salinity-driven stratification on the shelf, reducing the upwelling of nutrient-rich saline Pacific waters to the surface which also limited nutrient availability. This stratification and lower nutrient availability likely limited primary productivity and the presence of ammonia-oxidizers on the Beaufort Shelf. It is important to note that sea level on the Beaufort Shelf was > 60 m lower in the Early Holocene than it is today (Fig. 4e). Implying that between 10–12 ka, the Beaufort Sea was a shallow estuarine environment (Fig. 4g; Hill et al., 1993).

The concentration of brGDGTs and terrestrial sterols in the shelf slope location during the Early Holocene peaked at 11.3 ± 0.3 and 8.2 ± 0.5 ka (Fig. 3i, j), which agrees with meltwater outflow from the LIS and freshly deglaciated surfaces as seen in nearby cores (Klotsko et al., 2019; Wu et al., 2020a). Additionally, increased freshwater input may have transported more detrital calcium (Ca), as indicated by elevated Ca Ti ratios (Fig. 2a), which could have enhanced the preservation of foraminifera by buffering the water column and limiting carbonate dissolution, in sediments along the shelf slope. Murton et al. (2010) used optically stimulated luminescence (OSL) dating to identify two major meltwater pulses through the Mackenzie River system between 13 and 11.7 ka and between 11.7 and 9.3 ka. This timing is supported by sedimentary and isotopic records from the Beaufort Sea indicating a major Lake Agassiz flood route through the Mackenzie system (Keigwin et al., 2018; Klotsko et al., 2019). These meltwater events coincide with events (11.3 ± 0.3, 8.2 ± 0.5 ka) in the biomarker records from this study (Fig. 3), and one event at 10.1 ± 0.4 ka is recorded in the reconstructed salinity (Fig. 4b), suggesting enhanced freshwater forcing impacted ocean circulation and increased sea ice extent. The massive meltwater discharge from the LIS (at least ∼ 9000 km3) into its surrounding oceans has been the major cause for eustatic sea level rise from 10 to 6 ka (Moran and Bryson, 1969).

4.2 Middle to Late Holocene (8.2–0 ka)

After 8.2 ka, environmental conditions at the shelf slope (PCB09) and the outer shelf (PCB11) diverged markedly, reflecting their contrasting depositional and oceanographic settings. At PCB09, SSTs cooled from ∼ 6 to 3 °C (Fig. 4d), while steadily increasing sea-ice biomarker concentrations led to PIP25 > 0.5 by 7–6 ka, indicating the establishment of stable ice-edge or polynya conditions at the slope. The higher salinity (Fig. 4b) and greater distance from the coast at this site suggest enhanced influence of offshore Pacific-derived waters and reduced terrestrial input.

In contrast, at the outer shelf site PCB11, sea-ice biomarkers also increased after 8.5 ka but were accompanied by persistently high concentrations of open-water diatom markers, implying continued seasonal sea-ice and productive flaw-lead conditions, i.e., an open-water or newly formed sea-ice zone between landfast ice and sea ice. The flaw-lead today occurs about 80 km away from shore (Fig. S1) (Carmack et al., 2004). The proximity of PCB11 to the coastline before 6 ka (Fig. 4g) likely favored landfast-ice diatom assemblages and greater sensitivity to freshwater discharge. Only after 4 ± 0.5 ka did PCB11 reach PIP25 values comparable to the slope, indicating a delayed transition to stable seasonal sea ice, approximately 2 kyr later than at PCB09. Thus, while both sites record a Middle-Holocene trend toward increasing sea-ice cover, the slope experienced earlier stabilization and reduced productivity linked to offshore cooling and stratification, whereas the outer shelf remained a dynamic, seasonally open-water environment likely sustained by coastal flaw-lead formation, and strong riverine influence.

In the Late Holocene (4.2 ka to present), the two Beaufort sites again show distinct sea-ice and productivity trajectories reflecting their different hydrographic settings. At the slope site, perennial sea ice cover developed after 3 ka as indicated by higher PIP25 values (> 0.8), increased reconstructed salinity (Fig. 4a, b), as well as a decline in open-water diatom biomarkers (Fig. 3e, f). A sharp decrease in PIP25 and open-water diatom biomarkers at 1.5 ± 1.5 ka suggests a shift to year-round ice cover coincident with low SST (∼ 0 °C, Fig. 4d). The parallel reduction in heterotrophic archaeal production may reflect strengthened water-column stratification or reduced nutrient supply, consistent with restricted shelf-break upwelling (Schulze and Pickart, 2012). These changes are broadly consistent with the timing of the regional cooling associated with the Little Ice Age (Mann et al., 2009), although the resolution of the biomarker record does not allow precise attribution to centennial-scale events. In contrast, on the outer shelf, seasonal sea-ice conditions persisted longer and sea ice cover expanded gradually and became well established after about 2 ± 0.6 ka. Even as sea-ice biomarkers increased, open-water diatom markers remained relatively abundant, implying continued flaw-lead or marginal-ice-zone productivity sustained by intermittent open-water formation and coastal influence.

By the last 0.4 ka, both sites reached modern configurations, but with clear spatial differences: PCB09 records persistently thick, multi-year ice and limited primary production, whereas PCB11 retains higher concentrations of both sea-ice and open-water diatom biomarkers, consistent with modern flaw-lead dynamics observed near the outer shelf (Fig. S1).

4.3 Comparison with other Arctic marginal seas

Previous studies using IP25 to reconstruct sea ice variability in Arctic marginal seas have reported largely open-water conditions with significant freshwater influence during the Late glacial to Early Holocene.

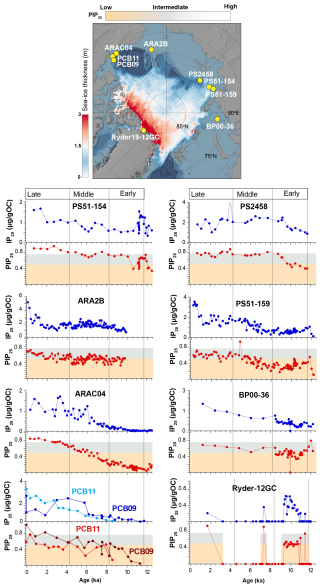

Figure 5Arctic sea-ice records (PIP25 and IP25 concentration) covering the Holocene: PCB (this study), ARAC04 (Wu et al., 2020a), ARA2B (Stein et al., 2017), PS51-154 and PS51-159 (Hörner et al., 2016), PS5428 (Fahl and Stein, 2012), BP0036 (Hörner et al., 2018), Ryder19-12 (Detlef et al., 2023). Average thickness of sea ice (in meters) for September 2023. Data from the Arctic Ocean Sea Ice Reanalysis (Williams et al., 2021) obtained via the E.U. Copernicus Marine Service Information MyOcean Viewer (https://marine.copernicus.eu/access-data/myocean-viewer, last access: 1 October 2025). The shaded rectangles indicate the limit of the proxy for no sea-ice in red, seasonal sea ice in blue (0.5 < PIP25 < 0.75) and permanent sea ice above PIP25 > 0.75.

The nearby cores JPC15 (Keigwin et al., 2018), ARAC20 (Wu et al., 2020a) (Fig. 1) recorded similar environmental changes (sea ice cover, freshwater input) as in PCB09 but different from those recorded in the shallow PCB11 site, highlighting the differences between shelf slope and outer shelf and the spatial variation of the polynya position. Aside from the close-by cores (Keigwin et al., 2018; Klotsko et al., 2019; Wu et al., 2020a), other Arctic records in the Canadian Archipelago (Vare et al., 2009), East Siberian (Dong et al., 2022), Kara (Hörner et al., 2018) , Chukchi (Stein et al., 2017), Laptev (Fahl and Stein, 2012; Hörner et al., 2016), and Lincoln (Detlef et al., 2023) Seas and along the Lomonosov Ridge (Stein and Fahl, 2012), report minimum sea-ice cover during the Early Holocene (centered around 10 ka) (Fig. 5). Detlef et al. (2023) reconstructed sea ice conditions from a sediment core covering the last 11 ka, showing that while the Lincoln Sea currently experiences perennial sea ice cover (PIP25 = 0), it underwent a shift to seasonal sea ice during the Early Holocene (around 10 ka) due to significantly warmer conditions (PIP25 > 0.5). This period of reduced sea ice cover is associated with increased marine productivity and meltwater input indicated by biomarker and sedimentary facies. The Northern Greenland (Detlef et al., 2023) and the site offshore the Laptev Sea on the Lomonosov Ridge (Fahl and Stein, 2012; Hörner et al., 2016) are the first regions to record permanent sea-ice cover beginning around 9 ka after the Early Holocene minimum. The Beaufort Sea (this study; Wu et al., 2020a) showed permanent sea-ice cover over the slope after 3 ka. Seasonal sea-ice cover in the shallower regions of the Laptev and Beaufort Seas (PS51-159 and PCB11) was developed after 5 and 3 ka, respectively. The Chukchi Sea (ARA2B) had seasonal sea-ice from the Mid-Holocene onwards, with an increase after 4.5 ka (Stein et al., 2017). The variations in sea ice cover and primary production in the Chukchi Sea were attributed to differences in solar insolation and variability in Pacific water inflow, which brought increased heat flux and episodic declines in sea ice cover. In the Canadian Archipelago, a record that did not include the Early Holocene (Belt et al., 2010; Vare et al., 2009), increased sea-ice cover exists from from 7 to 3 ka.

In contrast, studies using dinocyst assemblages from around the Arctic Ocean (see the review of de Vernal et al., 2013) report constant sea ice cover for the Early to Mid-Holocene with a clear decrease around 6 ka, followed by a return to pre-6 ka conditions until an increase toward modern times. This could be due to a warm-bias in the dinocyst estimate or a non-representative training set (de Vernal et al., 2013).

Together, many of the biomarker studies provide a consistent narrative of spring sea ice development during the Holocene across the Arctic Ocean following a period of high insolation in the Early Holocene. The transition from largely open-water and freshwater-influenced conditions during the Late glacial to Early Holocene to increasing sea ice cover from the Mid-Holocene onward is a shared feature across the Arctic shelf seas, although regional variations in sea ice dynamics and productivity are observed due to local freshwater input and oceanographic conditions. Evidence from areas with permanent sea ice, such as the Lincoln Sea, shows that the minimum ice cover during the Late glacial extended even into the high Arctic, offering insights into the extent of sea ice reduction during this time.

Analysis of two sediment cores from the outer Beaufort Shelf and shelf slope help elucidate the region's paleoenvironmental variability throughout the Holocene. The shelf slope experienced ice-free to minimal sea ice extent during the Late glacial and Early Holocene. During the Early Holocene, the Beaufort Shelf was ∼ 60 m shallower than today, and experienced large freshwater influxes due to the decaying LIS. The following sea level rise brought the core sites further away from the river mouth and eroding permafrost coasts, lowering the input of terrestrial organic matter. Cooling during the Mid-Holocene drove an increase in sea ice cover for the Beaufort Shelf and other Arctic marginal seas. Sea-ice cover and its impact on local upwelling and regional Pacific inflow impacted local primary production, concentrating the phytoplankton production in open-water flaw-lead or polynya conditions. Open water conditions substantially decreased during the Late Holocene as extended sea ice cover developed at the shelf slope, which caused primary productivity to further decline. This study highlights broadly consistent patterns of sea ice variability across Arctic marginal seas, implying similar controls on sea-ice dynamics, and underscoring the vulnerability of perennial sea-ice as contemporary climate conditions reach or surpass those from the Early Holocene.

The research data are published on the Bolin Center database https://doi.org/10.17043/lattaud-2025-sediment-beaufort-surface-1 (Lattaud et al., 2025a) and https://doi.org/10.17043/lattaud-2025-sediment-beaufort-1 (Lattaud et al., 2025b).

The supplement related to this article is available online at https://doi.org/10.5194/cp-22-187-2026-supplement.

MS: Data Curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – original draft preparation. LBr: Conceptualization, Supervision, Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing. MO: Resource, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. IH: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. TT: Resource, Writing – review & editing. LBi: Investigation. NH: Resource, Writing – review & editing. DN: Resource, Writing – review & editing. MF: Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing. JL: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

The contact author has declared that none of the authors has any competing interests.

Publisher's note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims made in the text, published maps, institutional affiliations, or any other geographical representation in this paper. The authors bear the ultimate responsibility for providing appropriate place names. Views expressed in the text are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher.

We thank Amundsen Science and ArcticNet for their support in preparing the cruise and the crew of the CCGS Amundsen and the PeCaBeau team for their help during sampling. We thank the Alfred Wegener Institute for providing the multicorer and part of the logistical support. Carina Johansson is thanked for her help with XRF analysis, and Axel Birkholz and Thomas Kuhn for the bulk elemental and isotopic analysis.

This research has been supported by the Swiss Polar Institute (grant no. PAF-2020-004), the Schweizerischer Nationalfonds zur Förderung der Wissenschaftlichen Forschung (grant no. PZ00P2-209012), and the Horizon 2020 (grant no. 730965).

The publication of this article was funded by the Swedish Research Council, Forte, Formas, and Vinnova.

This paper was edited by Odile Peyron and reviewed by three anonymous referees.

Allan, E., Douglas, P. M. J., de Vernal, A., Gélinas, Y., and Mucci, A. O.: Palmitic Acid Is Not a Proper Salinity Proxy in Baffin Bay and the Labrador Sea but Reflects the Variability in Organic Matter Sources Modulated by Sea Ice Coverage, Geochem. Geophys. Geosystems, 24, e2022GC010837, https://doi.org/10.1029/2022GC010837, 2023.

Barrientos, N., Lear, C. H., Jakobsson, M., Stranne, C., O'Regan, M., Cronin, T. M., Gukov, A. Y., and Coxall, H. K.: Arctic Ocean benthic foraminifera Mg Ca ratios and global Mg Ca-temperature calibrations: New constraints at low temperatures, Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta, 236, 240–259, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gca.2018.02.036, 2018.

Belt, S. T., Massé, G., Rowland, S. J., Poulin, M., Michel, C., and LeBlanc, B.: A novel chemical fossil of palaeo sea ice: IP25, Org. Geochem., 38, 16–27, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.orggeochem.2006.09.013, 2007.

Belt, S. T., Vare, L. L., Massé, G., Manners, H. R., Price, J. C., MacLachlan, S. E., Andrews, J. T., and Schmidt, S.: Striking similarities in temporal changes to spring sea ice occurrence across the central Canadian Arctic Archipelago over the last 7000 years, Quat. Sci. Rev., 29, 3489–3504, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2010.06.041, 2010.

Belt, S. T., Brown, T. A., Ampel, L., Cabedo-Sanz, P., Fahl, K., Kocis, J. J., Massé, G., Navarro-Rodriguez, A., Ruan, J., and Xu, Y.: An inter-laboratory investigation of the Arctic sea ice biomarker proxy IP25 in marine sediments: key outcomes and recommendations, Clim. Past, 10, 155–166, https://doi.org/10.5194/cp-10-155-2014, 2014.

Belt, S. T., Cabedo-Sanz, P., Smik, L., Navarro-Rodriguez, A., Berben, S. M. P., Knies, J., and Husum, K.: Identification of paleo Arctic winter sea ice limits and the marginal ice zone: Optimised biomarker-based reconstructions of late Quaternary Arctic sea ice, Earth Planet. Sci. Lett., 431, 127–139, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2015.09.020, 2015.

Blaauw, M. and Christen, J. A.: Flexible paleoclimate age-depth models using an autoregressive gamma process, Bayesian Anal., 6, 457–474, https://doi.org/10.1214/11-BA618, 2011.

Bröder, L., O'Regan, M., Fritz, M., Juhls, B., Priest, T., Lattaud, J., Whalen, D., Matsuoka, A., Pellerin, A., Bossé-Demers, T., Rudbäck, D., Eulenburg, A., Carson, T., Rodriguez-Cuicas, M.-E., Overduin, P., and Vonk, J. E.: The Permafrost Carbon in the Beaufort Sea (PeCaBeau) Expedition of the Research Vessel CCGS AMUNDSEN (AMD2104) in 2021, Berichte Zur Polar-Meeresforsch. Rep. Polar Mar. Res., 759, https://doi.org/10.48433/BzPM_0759_2022, 2022.

Broecker, W. S., Kennett, J. P., Flower, B. P., Teller, J. T., Trumbore, S., Bonani, G., and Wolfli, W.: Routing of meltwater from the Laurentide Ice Sheet during the Younger Dryas cold episode, Nature, 341, 318–321, https://doi.org/10.1038/341318a0, 1989.

Carmack, E., Polyakov, I., Padman, L., Fer, I., Hunke, E., Hutchings, J., Jackson, J., Kelley, D., Kwok, R., Layton, C., Melling, H., Perovich, D., Persson, O., Ruddick, B., Timmermans, M.-L., Toole, J., Ross, T., Vavrus, S., and Winsor, P.: Toward Quantifying the Increasing Role of Oceanic Heat in Sea Ice Loss in the New Arctic, Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc., 96, 2079–2105, https://doi.org/10.1175/BAMS-D-13-00177.1, 2015.

Carmack, E. C., Macdonald, R. W., and Jasper, S.: Phytoplankton productivity on the Canadian Shelf of the Beaufort Sea, Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser., 277, 37–50, https://doi.org/10.3354/meps277037, 2004.

Clemens, S. C., Prell, W. L., and Sun, Y.: Orbital-scale timing and mechanisms driving Late Pleistocene Indo-Asian summer monsoons: Reinterpreting cave speleothem δ18O, Paleoceanography, 25, https://doi.org/10.1029/2010PA001926, 2010.

Comiso, J. C., Parkinson, C. L., Gersten, R., and Stock, L.: Accelerated decline in the Arctic sea ice cover, Geophys. Res. Lett., 35, 2007GL031972, https://doi.org/10.1029/2007GL031972, 2008.

Detlef, H., O'Regan, M., Stranne, C., Jensen, M. M., Glasius, M., Cronin, T. M., Jakobsson, M., and Pearce, C.: Seasonal sea-ice in the Arctic's last ice area during the Early Holocene, Commun. Earth Environ., 4, 1–11, https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-023-00720-w, 2023.

de Vernal, A., Hillaire-Marcel, C., Rochon, A., Fréchette, B., Henry, M., Solignac, S., and Bonnet, S.: Dinocyst-based reconstructions of sea ice cover concentration during the Holocene in the Arctic Ocean, the northern North Atlantic Ocean and its adjacent seas, Quat. Sci. Rev., 79, 111–121, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2013.07.006, 2013.

Dong, J., Shi, X., Gong, X., Astakhov, A. S., Hu, L., Liu, X., Yang, G., Wang, Y., Vasilenko, Y., Qiao, S., Bosin, A., and Lohmann, G.: Enhanced Arctic sea ice melting controlled by larger heat discharge of mid-Holocene rivers, Nat. Commun., 13, 5368, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-33106-1, 2022.

Fahl, K. and Stein, R.: Modern seasonal variability and deglacial/Holocene change of central Arctic Ocean sea-ice cover: New insights from biomarker proxy records, Earth Planet. Sci. Lett., 351–352, 123–133, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2012.07.009, 2012.

Fu, C. Y., Osman, M. B., and Aquino-López, M. A.: Bayesian Calibration for the Arctic Sea Ice Biomarker IP25, Paleoceanogr. Paleoclimatology, 40, e2024PA005048, https://doi.org/10.1029/2024PA005048, 2025.

Harning, D. J. and Sepúlveda, J.: Impact of non-thermal variables on hydroxylated GDGT distributions around Iceland, Front. Earth Sci., 12, https://doi.org/10.3389/feart.2024.1430441, 2024.

Heaton, T. J., Köhler, P., Butzin, M., Bard, E., Reimer, R. W., Austin, W. E. N., Bronk Ramsey, C., Grootes, P. M., Hughen, K. A., Kromer, B., Reimer, P. J., Adkins, J., Burke, A., Cook, M. S., Olsen, J., and Skinner, L. C.: Marine20 – The Marine Radiocarbon Age Calibration Curve (0–55 000 cal BP), Radiocarbon, 62, 779–820, https://doi.org/10.1017/rdc.2020.68, 2020.

Hill, P. R., Hequette, A., and Ruz, M. H.: Holocene sea-level history of the Canadian Beaufort shelf, Can. J. Earth Sci., 30, 103–108, https://doi.org/10.1139/e93-009, 1993.

Holmes, R. M., McClelland, J. W., Peterson, B. J., Tank, S. E., Bulygina, E., Eglinton, T. I., Gordeev, V. V., Gurtovaya, T. Y., Raymond, P. A., Repeta, D. J., Staples, R., Striegl, R. G., Zhulidov, A. V., and Zimov, S. A.: Seasonal and Annual Fluxes of Nutrients and Organic Matter from Large Rivers to the Arctic Ocean and Surrounding Seas, Estuaries Coasts, 35, 369–382, https://doi.org/10.1007/s12237-011-9386-6, 2012.

Hopmans, E. C., Weijers, J. W. H., Schefuß, E., Herfort, L., Sinninghe Damsté, J. S., and Schouten, S.: A novel proxy for terrestrial organic matter in sediments based on branched and isoprenoid tetraether lipids, Earth Planet. Sci. Lett., 224, 107–116, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2004.05.012, 2004.

Hopmans, E. C., Schouten, S., and Sinninghe Damsté, J. S.: The effect of improved chromatography on GDGT-based palaeoproxies, Org. Geochem., 93, 1–6, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.orggeochem.2015.12.006, 2016.

Hörner, T., Stein, R., Fahl, K., and Birgel, D.: Post-glacial variability of sea ice cover, river run-off and biological production in the western Laptev Sea (Arctic Ocean) – A high-resolution biomarker study, Quat. Sci. Rev., 143, 133–149, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2016.04.011, 2016.

Hörner, T., Stein, R., and Fahl, K.: Paleo-sea ice distribution and polynya variability on the Kara Sea shelf during the last 12 ka, Arktos, 4, 1–16, https://doi.org/10.1007/s41063-018-0040-4, 2018.

Huguet, C., Hopmans, E. C., Febo-Ayala, W., Thompson, D. H., Sinninghe Damsté, J. S., and Schouten, S.: An improved method to determine the absolute abundance of glycerol dibiphytanyl glycerol tetraether lipids, Org. Geochem., 37, 1036–1041, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.orggeochem.2006.05.008, 2006.

Jakobsson, M., Mohammad, R., Karlsson, M., Salas-Romero, S., Vacek, F., Heinze, F., Bringensparr, C., Castro, C. F., Johnson, P., Kinney, J., Cardigos, S., Bogonko, M., Accettella, D., Amblas, D., An, L., Bohan, A., Brandt, A., Bünz, S., Canals, M., Casamor, J. L., Coakley, B., Cornish, N., Danielson, S., Demarte, M., Di Franco, D., Dickson, M.-L., Dorschel, B., Dowdeswell, J. A., Dreutter, S., Fremand, A. C., Hall, J. K., Hally, B., Holland, D., Hong, J. K., Ivaldi, R., Knutz, P. C., Krawczyk, D. W., Kristofferson, Y., Lastras, G., Leck, C., Lucchi, R. G., Masetti, G., Morlighem, M., Muchowski, J., Nielsen, T., Noormets, R., Plaza-Faverola, A., Prescott, M. M., Purser, A., Rasmussen, T. L., Rebesco, M., Rignot, E., Rysgaard, S., Silyakova, A., Snoeijs-Leijonmalm, P., Sørensen, A., Straneo, F., Sutherland, D. A., Tate, A. J., Travaglini, P., Trenholm, N., van Wijk, E., Wallace, L., Willis, J. K., Wood, M., Zimmermann, M., Zinglersen, K. B., and Mayer, L.: The International Bathymetric Chart of the Arctic Ocean Version 5.0, Sci. Data, 11, 1420, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-024-04278-w, 2024.

Kashiwase, H., Ohshima, K. I., Nihashi, S., and Eicken, H.: Evidence for ice-ocean albedo feedback in the Arctic Ocean shifting to a seasonal ice zone, Sci. Rep., 7, 8170, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-08467-z, 2017.

Kaufman, D. S., Ager, T. A., Anderson, N. J., Anderson, P. M., Andrews, J. T., Bartlein, P. J., Brubaker, L. B., Coats, L. L., Cwynar, L. C., Duvall, M. L., Dyke, A. S., Edwards, M. E., Eisner, W. R., Gajewski, K., Geirsdóttir, A., Hu, F. S., Jennings, A. E., Kaplan, M. R., Kerwin, M. W., Lozhkin, A. V., MacDonald, G. M., Miller, G. H., Mock, C. J., Oswald, W. W., Otto-Bliesner, B. L., Porinchu, D. F., Rühland, K., Smol, J. P., Steig, E. J., and Wolfe, B. B.: Holocene thermal maximum in the western Arctic (0–180° W), Quat. Sci. Rev., 23, 529–560, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2003.09.007, 2004.

Keigwin, L. D., Klotsko, S., Zhao, N., Reilly, B., Giosan, L., and Driscoll, N. W.: Deglacial floods in the Beaufort Sea preceded Younger Dryas cooling, Nat. Geosci., 11, 599–604, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41561-018-0169-6, 2018.

Klotsko, S., Driscoll, N., and Keigwin, L.: Multiple meltwater discharge and ice rafting events recorded in the deglacial sediments along the Beaufort Margin, Arctic Ocean, Quat. Sci. Rev., 203, 185–208, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2018.11.014, 2019.

Kolling, H. M., Stein, R., Fahl, K., Sadatzki, H., de Vernal, A., and Xiao, X.: Biomarker Distributions in (Sub)-Arctic Surface Sediments and Their Potential for Sea Ice Reconstructions, Geochem. Geophys. Geosystems, 21, e2019GC008629, https://doi.org/10.1029/2019GC008629, 2020.

Köseoğlu, D., Belt, S. T., Smik, L., Yao, H., Panieri, G., and Knies, J.: Complementary biomarker-based methods for characterising Arctic sea ice conditions: A case study comparison between multivariate analysis and the PIP25 index, Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta, 222, 406–420, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gca.2017.11.001, 2018.

Kristjánsdóttir, G. B., Lea, D. W., Jennings, A. E., Pak, D. K., and Belanger, C.: New spatial Mg Ca-temperature calibrations for three Arctic, benthic foraminifera and reconstruction of north Iceland shelf temperature for the past 4000 years, Geochem. Geophys. Geosystems, 8, https://doi.org/10.1029/2006GC001425, 2007.

Lake, R. A.: Heat exchange between water and ice in the Arctic Ocean, Arch. Meteorol. Geophys. Bioklimatol. Ser. A, 16, 242–259, https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02246401, 1967.

Lambeck, K., Rouby, H., Purcell, A., Sun, Y., and Sambridge, M.: Sea level and global ice volumes from the Last Glacial Maximum to the Holocene, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci., 111, 15296–15303, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1411762111, 2014.

Lannuzel, D., Tedesco, L., van Leeuwe, M., Campbell, K., Flores, H., Delille, B., Miller, L., Stefels, J., Assmy, P., Bowman, J., Brown, K., Castellani, G., Chierici, M., Crabeck, O., Damm, E., Else, B., Fransson, A., Fripiat, F., Geilfus, N.-X., Jacques, C., Jones, E., Kaartokallio, H., Kotovitch, M., Meiners, K., Moreau, S., Nomura, D., Peeken, I., Rintala, J.-M., Steiner, N., Tison, J.-L., Vancoppenolle, M., Van der Linden, F., Vichi, M., and Wongpan, P.: The future of Arctic sea-ice biogeochemistry and ice-associated ecosystems, Nat. Clim. Change, 10, 983–992, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-020-00940-4, 2020.

Laskar, J., Robutel, P., Joutel, F., Gastineau, M., Correia, A. C. M., and Levrard, B.: A long-term numerical solution for the insolation quantities of the Earth, Astron. Astrophys., 428, 261–285, https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361:20041335, 2004.

Lattaud, J., Erdem, Z., Weiss, G. M., Rush, D., Balzano, S., Chivall, D., Meer, M. T. J. V. D., Hopmans, E. C., Sinninghe, J. S., Schouten, S., van der Meer, M. T. J., Hopmans, E. C., Sinninghe Damsté, J. S., and Schouten, S.: Hydrogen isotopic ratios of long-chain diols reflect salinity, Org. Geochem., 137, 103904, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.orggeochem.2019.103904, 2019.

Lattaud, J., Bröder, L., Haghipour, N., Rickli, J., Giosan, L., and Eglinton, T. I.: Influence of Hydraulic Connectivity on Carbon Burial Efficiency in Mackenzie Delta Lake Sediments, J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosciences, 126, https://doi.org/10.1029/2020jg006054, 2021a.

Lattaud, J., De Jonge, C., Elling, F. J., Pearson, A., and Eglinton, T. I.: Microbial lipid signatures in Arctic deltaic sediments – Insights into methane cycling and climate variability, Org. Geochem., 157, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.orggeochem.2021.104242, 2021b.

Lattaud, J., Santos, M., Bröder, L., and Bigler, L.: Beaufort Sea surface sediment hydrogen isotope ratios from expeditions AMD2104 and SKQ2022-15s, 2021 and 2022, Dataset version 1, Bolin Centre Database [data set], https://doi.org/10.17043/lattaud-2025-sediment-beaufort-surface-1, 2025a.

Lattaud, J., Santos, M., Bröder, L., Hernandez, I., and O'Regan, M.: Sediment properties of Beaufort Sea sediment cores PCB09 and PCB11 – foraminifera counts and biomarkers, Dataset version 1, Bolin Centre Database [data set], https://doi.org/10.17043/lattaud-2025-sediment-beaufort-1, 2025b.

Lin, T.-W., Tesi, T., Hefter, J., Grotheer, H., Wollenburg, J., Adolphi, F., Bauch, H. A., Nogarotto, A., Müller, J., and Mollenhauer, G.: Environmental controls of rapid terrestrial organic matter mobilization to the western Laptev Sea since the Last Deglaciation, Clim. Past, 21, 753–772, https://doi.org/10.5194/cp-21-753-2025, 2025.

Liu, X.-L., Lipp, J. S., Simpson, J. H., Lin, Y.-S., Summons, R. E., and Hinrichs, K.-U.: Mono- and dihydroxyl glycerol dibiphytanyl glycerol tetraethers in marine sediments: Identification of both core and intact polar lipid forms, Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta, 89, 102–115, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gca.2012.04.053, 2012.

Locarnini, R. A., Mishonov, A. V., Baranova, O. K., Reagan, J. R., Boyer, T. P., Seidov, D., Wang, Z., Garcia, H. E., Bouchard, C., Cross, S. L., Paver, C. R., and Dukhovskoy, D.: World Ocean Atlas 2023, Volume 1: Temperature, https://doi.org/10.25923/54BH-1613, 2024.

Lü, X., Liu, X.-L., Elling, F. J., Yang, H., Xie, S., Song, J., Li, X., Yuan, H., Li, N., and Hinrichs, K.-U.: Hydroxylated isoprenoid GDGTs in Chinese coastal seas and their potential as a paleotemperature proxy for mid-to-low latitude marginal seas, Org. Geochem., 89–90, 31–43, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.orggeochem.2015.10.004, 2015.

Mann, M. E., Zhang, Z., Rutherford, S., Bradley, R. S., Hughes, M. K., Shindell, D., Ammann, C., Faluvegi, G., and Ni, F.: Global Signatures and Dynamical Origins of the Little Ice Age and Medieval Climate Anomaly, Science, 326, 1256–1260, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1177303, 2009.

Matsuoka, A., Bricaud, A., Benner, R., Para, J., Sempéré, R., Prieur, L., Bélanger, S., and Babin, M.: Tracing the transport of colored dissolved organic matter in water masses of the Southern Beaufort Sea: relationship with hydrographic characteristics, Biogeosciences, 9, 925–940, https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-9-925-2012, 2012.

Meier, W., Markus, T., and Comiso, J.: AMSR-E/AMSR2 Unified L3 Daily 12.5 km Brightness Temperatures, Sea Ice Concentration, Motion & Snow Depth Polar Grids, Version 1, National Snow and Ice Data Center, https://doi.org/10.5067/RA1MIJOYPK3P, 2018.

Missiaen, L., Wacker, L., Lougheed, B. C., Skinner, L., Hajdas, I., Nouet, J., Pichat, S., and Waelbroeck, C.: Radiocarbon Dating of Small-sized Foraminifer Samples: Insights into Marine sediment Mixing, Radiocarbon, 62, 313–333, https://doi.org/10.1017/RDC.2020.13, 2020.

Moran, J. M. and Bryson, R. A.: The Contribution of Laurentide Ice Wastage to the Eustatic Rise of Sea Level: 10,000 to 6,000 BP, Arct. Alp. Res., 1, 97–104, https://doi.org/10.1080/00040851.1969.12003527, 1969.

Müller, J., Wagner, A., Fahl, K., Stein, R., Prange, M., and Lohmann, G.: Towards quantitative sea ice reconstructions in the northern North Atlantic: A combined biomarker and numerical modelling approach, Earth Planet. Sci. Lett., 306, 137–148, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2011.04.011, 2011.

Murton, J. B., Bateman, M. D., Dallimore, S. R., Teller, J. T., and Yang, Z.: Identification of Younger Dryas outburst flood path from Lake Agassiz to the Arctic Ocean, Nature, 464, 740–743, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature08954, 2010.

Omstedt, A., Carmack, E. C., and Macdonald, R. W.: Modeling the seasonal cycle of salinity in the Mackenzie shelf/estuary, J. Geophys. Res. Oceans, 99, 10011–10021, https://doi.org/10.1029/94JC00201, 1994.

Park, H.-S., Kim, S.-J., Seo, K.-H., Stewart, A. L., Kim, S.-Y., and Son, S.-W.: The impact of Arctic sea ice loss on mid-Holocene climate, Nat. Commun., 9, 4571, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-07068-2, 2018.

Peltier, W. R., Argus, D. F., and Drummond, R.: Space geodesy constrains ice age terminal deglaciation: The global ICE-6G_C (VM5a) model, J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth, 120, 450–487, https://doi.org/10.1002/2014JB011176, 2015.

Peterse, F., Kim, J.-H., Schouten, S., Kristensen, D. K., Koç, N., and Damsté, J. S. S.: Constraints on the application of the MBT/CBT palaeothermometer at high latitude environments (Svalbard, Norway), Org. Geochem., 40, 692–699, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.orggeochem.2009.03.004, 2009.

Pickart, R. S.: Shelfbreak circulation in the Alaskan Beaufort Sea: Mean structure and variability, J. Geophys. Res. Oceans, 109, 2003JC001912, https://doi.org/10.1029/2003JC001912, 2004.

Richerol, T., Rochon, A., Blasco, S., Scott, D. B., Schell, T. M., and Bennett, R. J.: Evolution of paleo sea-surface conditions over the last 600 years in the Mackenzie Trough, Beaufort Sea (Canada), Mar. Micropaleontol., 68, 6–20, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marmicro.2008.03.003, 2008.

Ruan, J., Huang, Y., Shi, X., Liu, Y., Xiao, W., and Xu, Y.: Holocene variability in sea surface temperature and sea ice extent in the northern Bering Sea: A multiple biomarker study, Org. Geochem., 113, 1–9, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.orggeochem.2017.08.006, 2017.

Sachs, J. P., Stein, R., Maloney, A. E., and Wolhowe, M.: An Arctic Ocean paleosalinity proxy from δ2H of palmitic acid provides evidence for deglacial Mackenzie River flood events An Arctic Ocean paleosalinity proxy from d 2 H of palmitic acid provides evidence for deglacial Mackenzie River fl ood events, Quat. Sci. Rev., 198, 76–90, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2018.08.025, 2018.

Schlitzer, R.: Ocean Data VIew, https://odv.awi.de (last access: 1 May 2025), 2025.

Schouten, S., Hopmans, E. C., Damsté, J. S. S., and Sinninghe Damsté, J. S.: The organic geochemistry of glycerol dialkyl glycerol tetraether lipids: A review, Org. Geochem., 54, 19–61, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.orggeochem.2012.09.006, 2013.

Schulze, L. M. and Pickart, R. S.: Seasonal variation of upwelling in the Alaskan Beaufort Sea: Impact of sea ice cover, J. Geophys. Res. Oceans, 117, https://doi.org/10.1029/2012JC007985, 2012.

Serreze, M. C., Barrett, A. P., Slater, A. G., Woodgate, R. A., Aagaard, K., Lammers, R. B., Steele, M., Moritz, R., Meredith, M., and Lee, C. M.: The large-scale freshwater cycle of the Arctic, J. Geophys. Res. Oceans, 111, https://doi.org/10.1029/2005JC003424, 2006.

Sinninghe Damsté, J. S.: Spatial heterogeneity of sources of branched tetraethers in shelf systems: The geochemistry of tetraethers in the Berau River delta (Kalimantan, Indonesia), Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta, 186, 13–31, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gca.2016.04.033, 2016.

Smik, L., Cabedo-Sanz, P., and Belt, S. T.: Semi-quantitative estimates of paleo Arctic sea ice concentration based on source-specific highly branched isoprenoid alkenes: A further development of the PIP25 index, Org. Geochem., 92, 63–69, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.orggeochem.2015.12.007, 2016.

Stein, R. and Fahl, K.: A first souther Lomonosov Ridge (Arctic Ocean) 60 ka IP25 sea-ice record, Polarforschung, 82, 83–86, 2012.

Stein, R., Macdonald, R. W., Naidu, A. S., Yunker, M. B., Gobeil, C., Cooper, L. W., Grebmeier, J. M., Whitledge, T. E., Hameedi, M. J., Petrova, V. I., Batova, G. I., Zinchenko, A. G., Kursheva, A. V., Narkevskiy, E. V., Fahl, K., Vetrov, A., Romankevich, E. A., Birgel, D., Schubert, C., Harvey, H. R., and Weiel, D.: Organic Carbon in Arctic Ocean Sediments: Sources, Variability, Burial, and Paleoenvironmental Significance, in: The Organic Carbon Cycle in the Arctic Ocean, edited by: Stein, R. and MacDonald, R. W., Springer Berlin Heidelberg, Berlin, Heidelberg, 169–314, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-18912-8_7, 2004.

Stein, R., Fahl, K., Schade, I., Manerung, A., Wassmuth, S., Niessen, F., and Nam, S.-I.: Holocene variability in sea ice cover, primary production, and Pacific-Water inflow and climate change in the Chukchi and East Siberian Seas (Arctic Ocean), J. Quat. Sci., 32, 362–379, https://doi.org/10.1002/jqs.2929, 2017.

Stranne, C., Jakobsson, M., and Björk, G.: Arctic Ocean perennial sea ice breakdown during the Early Holocene Insolation Maximum, Quat. Sci. Rev., 92, 123–132, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2013.10.022, 2014.

Stroeve, J. C., Serreze, M. C., Holland, M. M., Kay, J. E., Malanik, J., and Barrett, A. P.: The Arctic's rapidly shrinking sea ice cover: a research synthesis, Clim. Change, 110, 1005–1027, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-011-0101-1, 2012.

Swärd, H., Andersson, P., Hilton, R., Vogt, C., and O'Regan, M.: Mineral and isotopic (Nd, Sr) signature of fine-grained deglacial and Holocene sediments from the Mackenzie Trough, Arctic Canada, Arct. Antarct. Alp. Res., 54, 346–367, 2022.

Vare, L. L., Massé, G., Gregory, T. R., Smart, C. W., and Belt, S. T.: Sea ice variations in the central Canadian Arctic Archipelago during the Holocene, Quat. Sci. Rev., 28, 1354–1366, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2009.01.013, 2009.

Varma, D., Hopmans, E. C., van Kemenade, Z. R., Kusch, S., Berg, S., Bale, N. J., Sangiorgi, F., Reichart, G.-J., Sinninghe Damsté, J. S., and Schouten, S.: Evaluating isoprenoidal hydroxylated GDGT-based temperature proxies in surface sediments from the global ocean, Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta, 370, 113–127, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gca.2023.12.019, 2024.

Varma, D., Yedema, Y. W., Peterse, F., Reichart, G.-J., Sinninghe Damsté, J. S., and Schouten, S.: Impact of terrestrial organic matter input on distributions of hydroxylated isoprenoidal GDGTs in marine sediments: Implications for OH-isoGDGT-based temperature proxies, Org. Geochem., 206, 105010, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.orggeochem.2025.105010, 2025.

Vilks, G.: Ecology of Recent Foraminifera on the Canadian Continental Shelf of the Arctic Ocean, in: The Arctic Seas: Climatology, Oceanography, Geology, and Biology, edited by: Herman, Y., Springer US, Boston, MA, 497–569, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4613-0677-1_21, 1989.

Wang, Y., Hendy, I. L., and Thunell, R.: Local and Remote Forcing of Denitrification in the Northeast Pacific for the Last 2000 Years, Paleoceanogr. Paleoclimatology, 34, 1517–1533, https://doi.org/10.1029/2019PA003577, 2019.

Wegner, C., Bennett, K. E., de Vernal, A., Forwick, M., Fritz, M., Heikkilä, M., Łacka, M., Lantuit, H., Laska, M., Moskalik, M., O'Regan, M., Pawłowska, J., Promińska, A., Rachold, V., Vonk, J. E., and Werner, K.: Variability in transport of terrigenous material on the shelves and the deep Arctic Ocean during the Holocene, Polar Res., https://doi.org/10.3402/polar.v34.24964, 2015.

Weiss, G. M., Schouten, S., Sinninghe Damsté, J. S., and van der Meer, M. T. J.: Constraining the application of hydrogen isotopic composition of alkenones as a salinity proxy using marine surface sediments, Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta, 250, 34–48, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gca.2019.01.038, 2019.

West, G., Nilsson, A., Geels, A., Jakobsson, M., Moros, M., Muschitiello, F., Pearce, C., Snowball, I., and O'Regan, M.: Late Holocene Paleomagnetic Secular Variation in the Chukchi Sea, Arctic Ocean, Geochem. Geophys. Geosystems, 23, e2021GC010187, https://doi.org/10.1029/2021GC010187, 2022.

Williams, T., Korosov, A., Rampal, P., and Ólason, E.: Presentation and evaluation of the Arctic sea ice forecasting system neXtSIM-F, The Cryosphere, 15, 3207–3227, https://doi.org/10.5194/tc-15-3207-2021, 2021.

Wollenburg, J. E., Matthiessen, J., Vogt, C., Nehrke, G., Grotheer, H., Wilhelms-Dick, D., Geibert, W., and Mollenhauer, G.: Omnipresent authigenic calcite distorts Arctic radiocarbon chronology, Commun. Earth Environ., 4, 136, https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-023-00802-9, 2023.

Wu, J., Stein, R., Fahl, K., Mollenhauer, G., Geibert, W., Syring, N., and Nam, S.: Deglacial to Holocene variability in surface water characteristics and major floods in the Beaufort Sea, Commun. Earth Environ., 1, 1–12, https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-020-00028-z, 2020a.

Wu, J., Stein, R., Sachs, J. P., Wolhowe, M., Fahl, K., and You, D.: Quantitative Estimates of Younger Dryas Freshening From Lipid δ2H Analysis in the Beaufort Sea, Geophys. Res. Lett., 52, e2024GL112485, https://doi.org/10.1029/2024GL112485, 2025.

Wu, L., Wilson, D. J., Wang, R., Yin, X., Chen, Z., Xiao, W., and Huang, M.: Evaluating Zr Rb Ratio From XRF Scanning as an Indicator of Grain-Size Variations of Glaciomarine Sediments in the Southern Ocean, Geochem. Geophys. Geosystems, 21, e2020GC009350, https://doi.org/10.1029/2020GC009350, 2020b.