the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

East Antarctic Ice Sheet variability in the central Transantarctic Mountains since the mid Miocene

Gordon R. M. Bromley

Greg Balco

Margaret S. Jackson

Allie Balter-Kennedy

Holly Thomas

The response of the East Antarctic Ice Sheet to warmer-than-present climate conditions has direct implications for projections of future sea level, ocean circulation, and global radiative forcing. Nonetheless, it remains uncertain whether the ice sheet is likely to undergo net loss due to amplified melting coupled with dynamic instabilities or whether such losses will be balanced, or even offset, by enhanced accumulation under a higher-precipitation regime. The glacial depositional record from the central Transantarctic Mountains (TAM) provides a robust geologic means to reconstruct the past behaviour of the East Antarctic Ice Sheet, including during periods thought to have been warmer than today, such as the mid-Pliocene Warm Period (∼3.3–3.0 Ma). This study describes a new surface-exposure-dated moraine record from Otway Massif in the central TAM spanning the last ∼9 Myr and synthesises these data in the context of previously published moraine chronologies constrained with cosmogenic nuclides. The resulting record, although fragmentary, represents the majority of direct and unambiguous terrestrial evidence for the existence and size of the East Antarctic Ice Sheet during the last 14 Myr, and it thus provides new insight into the long-term relationship between the ice sheet and global climate. At face value, the existing TAM moraine record does not exhibit a clear signature of the mid-Pliocene Warm Period, thus precluding a definitive verdict on the East Antarctic Ice Sheet's response to this event. In contrast, an apparent hiatus in moraine deposition both at Otway Massif and the neighbouring Roberts Massif suggests that the ice sheet surface in the central TAM was potentially lower than present during the late Miocene and earliest Pliocene.

- Article

(6285 KB) - Full-text XML

-

Supplement

(347 KB) - BibTeX

- EndNote

Relict glacial deposits preserved in the Transantarctic Mountains (TAM) constitute direct geologic evidence for the East Antarctic Ice Sheet (EAIS) having been present at certain times in the past and thus provide a terrestrial means for reconstructing former ice sheet configurations. In contrast, marine-based proxy records from the seas surrounding Antarctica, while more continuous and often better dated, are intrinsically indirect; inferences of former ice sheet extent and thickness based on such proxies are therefore speculative. To assess the long-term behaviour of the EAIS directly and from a terrestrial vantage, we describe the ages of relict glacial deposits in the central Transantarctic Mountains (TAM) constrained by cosmogenic nuclide surface-exposure dating. As the world's largest remaining ice sheet, the configuration of the EAIS and its sensitivity to radiative forcing have direct implications for sea level and ocean circulation, and thus global climate, under amplified greenhouse conditions. In recent decades, observational data have revealed a considerable degree of ice marginal variability (e.g. changes in ice flow velocity, grounding line position, and ice shelf thickness) in East Antarctica, potentially reflecting the influence of rising ocean temperature on the stability of submarine grounding lines (Li et al., 2015; Rintoul et al., 2016; Konrad et al., 2018; Brancato et al., 2020; Noble et al., 2020). Inland, however, evidence for an EAIS response to climate forcing is less conclusive, in part due to the continental scale of the ice sheet and the relatively short observational periods involved (Stokes et al., 2022). Consequently, it remains uncertain whether the EAIS is likely to undergo net loss due to amplified melting at the margins coupled with dynamic instabilities (Golledge et al., 2015; DeConto and Pollard, 2016) or whether such losses will be balanced (or even offset) by enhanced accumulation under higher-precipitation conditions (e.g. Davis et al., 2005; Gregory and Huybrechts, 2006; Rapley, 2006; Boening et al., 2012; King et al., 2012; Winkelmann et al., 2012; Zwally et al., 2015; The IMBIE Team et al., 2018).

To explore this question further, a growing body of palaeoclimate research has sought to establish how the EAIS responded to past periods of relative warmth, including previous interglacials (DeConto and Pollard, 2016), the mid-Pliocene Warm Period (MPWP: ∼3.3–3.0 Ma), and the late Miocene. Of these, the MPWP has received particular attention as it affords, arguably, a closer analogue for our future than any other period since (e.g. Zubakov and Borzenkova, 1988; Dowsett and Cronin, 1990; Bart, 2001; Huybrechts, 2009; Yamane et al., 2015; Blasco et al., 2024; Burke et al., 2018; McClymont et al., 2020): average MPWP temperatures were elevated relative to today (e.g. Budyko, 1982; Dowsett et al., 2009; Lunt et al., 2010; Haywood et al., 2013, 2020; Burton et al., 2023), while sea level was generally higher (Raymo et al., 2006; Miller et al., 2020), although reconstructions of the latter remain highly variable (+15–60 m) (Miller et al., 2012; Levermann et al., 2013; Rovere et al., 2014; Dumitru et al., 2019; Hearty et al., 1999; Richards et al., 2022). The contribution of the EAIS to past ocean volume and ultimately ocean circulation is thus an outstanding question in climate science. Further, geology-based reconstructions of the Antarctic cryosphere provide a crucial test of the palaeoenvironmental parameters (e.g. PRISM4) currently used by the Pliocene Model Intercomparison Project Phase 2 (PlioMIP2) and which include substantial differences in ice sheet surface elevation relative to today (Dowsett et al., 2016).

To date, the majority of proxy-based assessments have inferred long-term EAIS variability from marine geological data. However, these offshore records display a considerable and sometimes conflicting range of potential ice sheet configurations. For instance, whereas sedimentological data from McMurdo Sound indicate persistent cold-based conditions along the ice sheet margins throughout the Pliocene (Barrett and Hambrey, 1992; McKay et al., 2009), despite generally warmer sea surface temperatures (Scherer et al., 2007; Naish et al., 2009), ice-rafted debris (IRD) provenance studies posit a dynamically unstable EAIS and widespread collapse of marine-based sectors, such as the Aurora and Wilkes basins (Fig. 1), during warmer periods (Williams et al., 2010; Pierce et al., 2011; Cook et al., 2013; Tauxe et al., 2015; Valletta et al., 2018). Meanwhile, interpretations of seafloor morphology on the Antarctic continental shelf have invoked expansion of the EAIS during the Pliocene due to enhanced accumulation (Bart and Anderson, 2000; Bart, 2001; Cowan, 2002), a scenario supported by some model simulations (Hill et al., 2007) and evidence for accumulation-induced thickening of EAIS outlet glaciers during Pleistocene interglacials (Higgins et al., 2000; Todd et al., 2010).

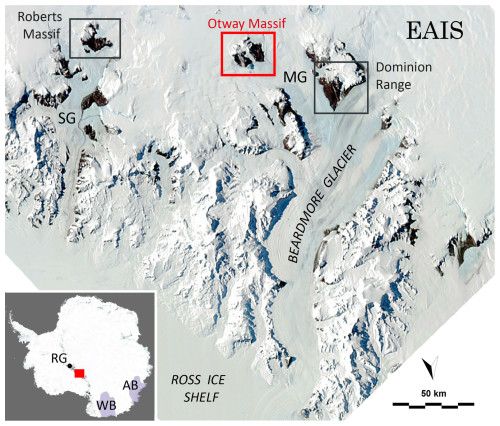

Figure 1Location map showing position of Otway Massif and other Transantarctic Mountain sites mentioned in the text. SG stands for Shackleton Glacier, MG stands for Mill Glacier, RG (inset map) stands for Reedy Glacier. Also shown are the respective positions of the Aurora (AB) and Wilkes (WB) subglacial basins (inset map).

The glacial geological record from Antarctica itself, although fragmentary due to the limited exposure of ice-free land, provides direct terrestrial evidence for past EAIS behaviour. Pioneering work by John Mercer on the glacial geology of the TAM identified two principal types of deposits, the first comprising lodgement tills emplaced by wet-based glaciation, the second characterised by loose and generally thin ablation tills (Mercer, 1968, 1972). The former – collectively termed the Sirius Group – have since been observed throughout the upper TAM (Barrett and Powell, 1982; McKelvey et al., 1991; Webb et al., 1987; Wilson et al., 1998; Balter-Kennedy et al., 2020), commonly overlying moulded and striated bedrock, and has been interpreted as representing overriding of the mountains by an enlarged EAIS (Mayewski, 1975; Denton et al., 1984, 1989; Webb et al., 1984; Marchant et al., 1993). While direct dating control for the Sirius Group is lacking and recognising that these wet-based deposits likely represent multiple glacial episodes, a degree of minimum-limiting age constraint is afforded by overlying deposits at several sites (Marchant et al., 1996; Bruno et al., 1997; Schäfer et al., 1999; Ackert and Kurz, 2004), with the most recent data indicating emplacement at Roberts Massif prior to the late Miocene (Balter-Kennedy et al., 2020).

In contrast to the Sirius Group, the physical characteristics of the overlying deposits are more indicative of cold-based ice (Mercer, 1972; Bockheim et al., 1986; Prentice et al., 1986), suggesting that the EAIS is frozen to the bed throughout much of the high TAM. Moreover, the spatial distribution of relict cold-based deposits within the current landscape suggests an ice configuration similar to today: a large EAIS draining via TAM outlet glaciers into the Ross Sea Embayment (Bromley et al., 2010). These geologic observations, coupled with a bracketing 40Ar/39Ar age control from interbedded volcanic deposits in the McMurdo Dry Valleys, were used to argue for enduring cold polar conditions in East Antarctica potentially since the mid Miocene and, correspondingly, general stability of the EAIS since that time (Denton et al., 1993; Sugden et al., 1995; Marchant and Denton, 1996). In subsequent decades, the application of in situ cosmogenic nuclides to glacial deposits and buried ice in the central TAM has corroborated that model at least regionally, revealing that this sector of the EAIS has maintained a configuration broadly similar to today for much of the Pleistocene–Pliocene (Bibby et al., 2016; Bader et al., 2017; Kaplan et al., 2017; Bergelin et al., 2022) and latter Miocene (Balter-Kennedy et al., 2020) periods. Environmental conditions vary considerably in East Antarctica, however, and it is possible the EAIS has undergone greater variability in extent and/or volume in sectors far from the TAM. For instance, sedimentological data from Lambert Glacier – the catchment of which comprises 7 % of the EAIS – have been interpreted as indicating fjord conditions until the middle Pleistocene (Hambrey and McKelvey, 2000). Those authors posited that the EAIS was less extensive at that time, a scenario potentially supported by marine evidence from neighbouring Prydz Bay (Mahood and Barron, 1996; Quilty et al., 2000; Whitehead et al., 2005).

Taken together, the existing Antarctic dataset presents a variable view of long-term ice sheet behaviour, particularly during key periods of relative warmth. Most (but not all) direct terrestrial evidence suggests the EAIS maintained a configuration similar to present during some periods of apparently elevated atmospheric CO2 and climatic warmth. In contrast, the indirect marine record leaves open the possibility of larger-scale variability, including widespread retreat of marine-based sectors. To help address this knowledge gap, we synthesise the existing glacial geological dataset in the central and southern TAM spanning the last 15 Myr, focusing specifically on directly dated records constrained with cosmogenic nuclide surface-exposure dating. This synthesis comprises previously published data from Dominion Range (Ackert and Kurz, 2004) and Reedy Glacier (Bromley et al., 2010), the extensive Roberts Massif record (Balter-Kennedy et al., 2020), and our new dataset from Otway Massif in the central TAM (Fig. 1).

Otway Massif (−85.415, 172.780°; Fig. 1) overlooks the heads of the Mill Glacier and Mill Stream Glacier, two tributaries of the Beardmore Glacier, and comprises ∼100 km2 of mountainous polar desert terrain underlain primarily by Ferrar dolerite. The massif exhibits a high-relief relict alpine topography of horn peaks separated by aretes and glacially carved cirques and valleys and ranges in elevation from 2000 m at the modern ice surface to 3260 m. Previous work by Denton et al. (1989) mapped glacial deposits in the north-west sector of Otway Massif. Our investigation focuses on the range's north-eastern sector (Fig. 1), where the land surface adjacent Mill Stream Glacier forms a broad and shallow valley running parallel to the ice margin. Above this feature, low-angled slopes rise gradually for ∼2–3 km in a south-easterly direction towards the base of the Mt. Petlock–Mom Peak ridgeline. The undulating surface of these lower-elevation slopes (∼8 km2) is characterised by glacially scoured, moulded, and deeply oxidised bedrock knolls separated by shallow valleys; overlying this landscape are thin, poorly developed, and potentially sterile soils similar to those described by Dragone et al. (2021) for the high central TAM. Assuming past ice surface profiles were broadly similar to today, we posit that the EAIS margin here has remained relatively thin for the duration of our record due to the low-gradient landscape over which it fluctuated. Together with the prevailing cold-based regime, this minimally erosive glacial configuration has no doubt contributed to the widespread deposition and long-term preservation of the ablation tills and moraine ridges forming the basis for our cosmogenic surface-exposure chronology.

During the 2015–2016 austral summer, we mapped the distribution, elevation, and morphology of moraines and drift sheets onto 2 m resolution vertical satellite imagery provided by the Polar Geospatial Center, University of Minnesota. We collected samples for cosmogenic surface-exposure dating from the upper surfaces of stable boulders located on moraine crests and drift sheets using a hammer and chisel and/or drill and wedges to remove samples of 1–5 cm thickness. To minimise the impacts of post-depositional erosion or snow burial, we specifically targeted boulders with ≥0.5 m relief and lacking visible signs of anomalously extreme surface weathering. We avoided boulders exhibiting obvious signs of subglacial modification (e.g. moulding, polish, and striations) due to the risk of such clasts having originated from remobilised Sirius Group tills, outcrops of which occur locally at Otway Massif, and thus containing inherited cosmogenic nuclides (Balter-Kennedy et al., 2020). For each sample, we photographed, drew, and described each boulder and measured horizon shielding with a clinometer and compass; shielding values were calculated using the method of Balco et al. (2008). Boulder positions were recorded with a handheld GPS (∼6 m horizontal precision) and elevations measured with a barometer calibrated against temporary GNSS benchmarks and corrected to orthometric heights relative to the EGM96 geoid (full procedure described by Balter-Kennedy et al., 2020).

We measured cosmogenic helium-3 concentrations in pyroxene isolated from the dolerite using the protocol described by Balter-Kennedy et al. (2020; modified from Bromley et al., 2014). Following crushing and sieving, the 125–250 µm size fraction was boiled in 10 % HNO3 to remove metal oxides, after which we used heavy liquids (sodium polytungstate) to separate the heavier pyroxene from lighter components. Pyroxene aliquots were then leached in weak (5 %) hydrofluoric acid for 2 h to remove (1) adhering remnants of feldspar and glass and (2) the outer rims of pyroxene grains, which can contain elevated concentrations of radiogenic helium (Blard and Farley, 2008; Bromley et al., 2014). Finally, leached pyroxenes were passed through a Frantz magnetic separator before being hand-picked under a microscope to remove any remaining impurities. We measured helium concentrations in clean pyroxene separates at the Berkeley Geochronology Center using the “Ohio” MAP 215-50 sector field mass spectrometer; we also periodically analysed aliquots of the CRONUS-P pyroxene standard (Blard et al., 2015) alongside our samples during each measurement period. Full details of the helium measurement procedure, including analysis of procedural blanks, replicates, and lab standards, are provided by Balter-Kennedy et al. (2020). Between 2016 and 2019, we measured helium in samples from 52 boulders, 28 of which were analysed in replicate. As measured concentrations of non-cosmogenic helium in Ferrar dolerite ( atoms g−1; Ackert, 2000; Margerison et al., 2005; Kaplan et al., 2017), pyroxenes are typically <1 % of the average observed concentrations in samples from Otway Massif, and we assume all measured 3He in our samples is cosmogenic and thus make no correction for non-cosmogenic contributions.

Alongside the 3He analyses, we also measured cosmogenic 10Be and 21Ne in three sandstone clasts. We purified quartz via established physical and chemical procedures (Schaefer et al., 2009) at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (LLNL), whereupon beryllium was extracted by ion chromatography and converted to BeO. Ratios of in the three samples and one procedural blank were measured at LLNL relative to the 07KNSTD standard (Nishiizumi et al., 2007). Reported uncertainties incorporate uncertainties in accelerator mass spectrometry (AMS) measurements, process blanks, and carrier concentrations. We measured cosmogenic 21Ne in the same quartz separates used for 10Be at Berkeley Geochronology Center (BGC) using the procedure described by Balter-Kennedy et al. (2020).

We calculated surface-exposure ages using version 3 of the University of Washington online calculator (https://hess.ess.washington.edu, last access: 17 January 2025) as described by Balco et al. (2008) and subsequently updated, using the “primary” production rate calibration datasets for 10Be and 3He from Borchers et al. (2016). The production rate for 21Ne is calculated assuming a production ratio of 4.03, after Balco et al. (2019), Balco and Shuster (2009), and Kober et al. (2011). Production rates were scaled to each sample site using the time-variable “LSDn” model (Lifton et al., 2014) and the Antarctic atmosphere model of Stone (2000). A full description of our protocol for identifying likely outliers is given in Sect. 3.2.

3.1 Otway Massif surficial geomorphology

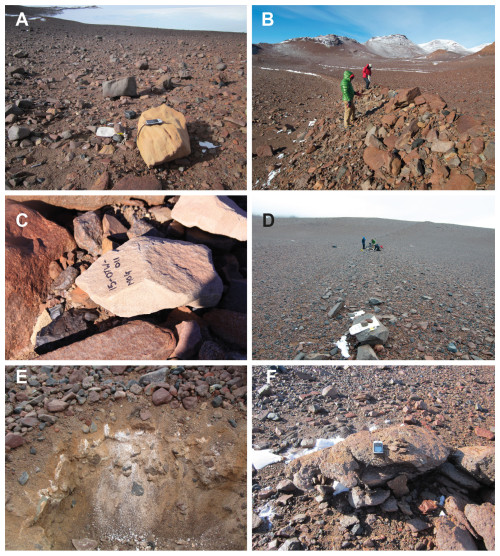

The lower reaches of Otway Massif are mantled by a thin and patchy cover of loose, coarse-grained till characterised by angular and sub-angular clasts, predominantly of dolerite lithology. Evidence for subglacial modification of the clasts (e.g. moulding, striations) is absent, suggesting deposition as an ablation till by cold-based ice. Punctuating this surface, numerous moraine ridges, some as large as 1.5 m in relief, are composed of boulders, cobbles, and gravel and mark different marginal positions of the EAIS. In all, we identified six prominent moraines (see Fig. 2 for moraine nomenclature), which are compositionally similar to the adjacent till but differ from one another in the degree of relative weathering, reflecting the time-transgressive nature of deposition. We describe both tills and moraines below in order from lowest to highest, which we interpret as youngest to oldest based on relative weathering criteria and exposure age data discussed below. Underlying the surficial polar ablation tills, we also observed conspicuous patches of a light-coloured, semi-lithified, clay-supported diamicton (Fig. 3) containing abundant sub-angular and sub-rounded clasts; many clasts bear striations, glacial polish, and clear evidence of glacial moulding. Reflecting the compositional and morphological contrast with the overlying ablation tills, we interpret this lower unit as lodgement till deposited under more temperate glaciologic conditions and potentially correlated with the Sirius Group (Mercer, 1972).

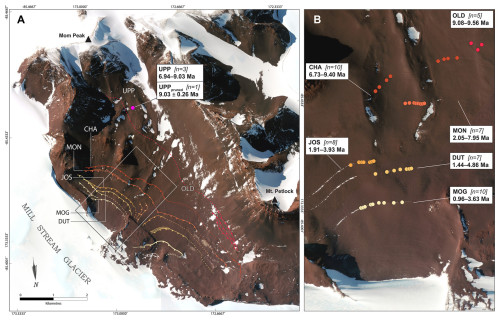

Figure 2Glacial geomorphic map and cosmogenic nuclide surface-exposure chronology of the Otway Massif study area. (a) Relative positions of moraines and drift edges marking the former extent of the Mill Stream Glacier (EAIS) margin. Dashed lines denote inferred drift edges. The white box indicates the area covered in panel (b). Also shown are the cosmogenic 3He surface-exposure ages for the Upper (UPP) drift unit for both single (n=3) and pruned (n=1) populations. Bold type denotes age ranges, while italics indicate mean ages. (b) Inset map of the Mogul (MOG), Dutch (DUT), Joshua (JOS), Montana (MON), Charlie (CHA), and Old (OLD) deposits and their corresponding 3He surface-exposure ages. Note that 10Be and 21Ne ages for the Mogul moraine are not shown. The base map is derived from WorldView-2 satellite imagery (© 2013, DigitalGlobe, Inc.).

Figure 3Examples of glacial geomorphology and relative weathering at Otway Massif. (a) Unweathered sandstone boulder perched on weathered dolerite-rich till, representing the most recent expansion of the EAIS at Otway Massif. (b) Southern section of the Mogul moraine. (c) Sandstone and dolerite boulders on the crest of the Mogul moraine, illustrating the moderate degree of surface staining on both lithologies. (d) Weathered boulders making up the Charlie moraine, the relief of which has been progressively lowered by inflation of the surrounding desert pavement (see Sect. 3.1). (e) Sub-surface salt accumulations revealed in a shallow excavation in the Charlie drift unit. (f) Severely weathered dolerite boulder on the surface of the Upper drift.

Within a few hundred metres of the modern ice margin, a thin veneer of fresh, unweathered dolerite and sandstone boulders represents the most recent advance of the EAIS along the north-eastern margin of Otway Massif (Fig. 3). While this relatively young unit is not associated with moraine landforms in this sector of Otway Massif, we note that in the north-western part of the range, Denton et al. (1989) reported two distinct units of thick, similarly fresh drift that are bounded by conspicuous moraine ridges. The lower of the two extends ∼8 m above the ice margin and was correlated by those authors with the Holocene Plunket drift (Denton et al., 1989), whereas the second, higher drift extends up to 40 m above the glacier surface and was correlated with the late Pleistocene (marine isotope stage 2) Beardmore drift. We sampled sandstone boulders from the fresh unit for 10Be dating; those data will be the focus of a separate paper covering the most recent EAIS behaviour in the central TAM.

Beyond the spread of fresh drift, the moraines and drift surfaces mapped in Fig. 2 appear generally more weathered with distance from the ice margin. Dolerite boulders on the Mogul moraine (Figs. 2 and 3), which demarks two separate lobes extending as much as a kilometre from the ice edge, exhibit moderate orange-brown staining to a depth of 1 mm, with shallow pitting on windward surfaces and light polish on lee surfaces. Sandstone boulders on this same landform are lightly exfoliated, exhibit minor pitting, and are lightly stained except for where flakes have been lost to weathering. Outboard of this unit, dolerite boulders on the Dutch moraine (Fig. 2) are marginally more weathered – exhibiting thicker (2 mm) weathering rinds, surface pits up to 1 cm in diameter, and well-developed desert varnish – while those associated with the Joshua moraine (Fig. 2) show advanced flaking and occasional cavernous weathering (Fig. 3); sandstone boulders on the latter moraine are highly disintegrated remnants. Farther from the modern ice margin, dolerite boulders associated with the Montana and Charlie moraines and the Old drift surface (Fig. 2) are highly weathered and many have developed a thick iron-oxide crusts (Fig. 3), which, despite being resistant to further surface weathering (e.g. pitting), are prone to break off in thick plates. By far the most aggressively weathered dolerite boulders we sampled, however, are those perched upon the Upper drift surface, one of which (15-OTW-058) exhibits fist-size caverns, while the remaining two (15-OTW-059 and 060) have undergone structural collapse (Fig. 3). For the Montana moraine and older deposits, centimetre-thick accumulations of salt or calcium carbonate occur on the undersides of most dolerite boulders. Moreover, we note that sandstone boulders are absent from these older deposits. As sandstone weathers faster than dolerite, its absence from these surfaces probably reflects the destructive impact of protracted exposure to weathering, and as such is a common characteristic of very old surfaces.

In arid polar environments such as the central TAM, the development of desert pavement provides an additional measure of relative age. Shallow (∼40 cm) excavations in the Montana moraine surface revealed a 2–3 cm thick surficial layer of loose medium- and coarse-grained sand, below which is a compacted unit of oxidised coarse sand, gravel, and cobbles, with the latter exhibiting moderate desert varnish. Thick salt layers are common throughout this compacted unit. Within the higher Old drift, we observed that the appearance of cobble-sized surface clasts exhibits a grain-size dependence; coarse-grained dolerite clasts are visibly exfoliated and crumbly, whereas fine-grained dolerite clasts tend to be of a highly desert-varnished appearance. Immediately beneath these surface clasts, a unit of unconsolidated medium- and coarse-grained sand extends to a depth of 5 cm and overlies a compacted horizon of deeply oxidised coarse sand and gravel and interbedded salt layers. The highest unit identified at Otway massif, the Upper drift, displays similar sub-surface sedimentological characteristics to the Old drift.

3.2 Correlative deposits in the central and southern TAM

Overall, the stratigraphy and morphology of glacial deposits at Otway Massif are nearly identical to those described by Balter-Kennedy et al. (2020) for Roberts Massif, which is located ∼100 km east of Otway Massif (Fig. 1) and underlain by the same dolerite–sandstone lithology. The last 15 Myr of ice sheet deposition at Roberts Massif is represented by at least 24 individual moraine or drift units, the oldest being positioned farthest from – and generally highest above – the modern ice margin (Balter-Kennedy et al., 2020). As summarised in Fig. 6, exposure ages for the highest Roberts Massif deposits range between ∼5 and 13 Ma (Misery Platform); stratigraphically and geomorphically, these deposits are analogous to the uppermost units observed at Otway Massif (Charlie, Old, Upper deposits). Indeed, the only significant disparity between the two sites is the relative abundance at Roberts Massif of highly weathered sandstone clasts, even within the oldest deposits on Southwest Col (see Fig. 9 of Balter-Kennedy et al., 2020). This feature reflects the extensive outcropping of Beacon sandstone at the head of Shackleton Glacier (Balter-Kennedy et al., 2020). Below the oldest Roberts Massif deposits, mid-elevation (Arena and Ringleader moraines) and low-elevation (e.g. northern and southern transects) landforms give age ranges of ∼0.5–3.2 Ma, respectively. Moraine ridges at both Roberts Massif and Otway Massif are nearly identical in relief, composition, relative weathering, and development of sub-surface salt layers.

Closer to Otway Massif, pre-Pleistocene deposits at Dominion Range (Fig. 1) also bear a strong similarity to those at our field site. Multiple studies have reported lateral moraines extending up to 2500 m elevation on the Oliver Platform and Mercer Platform (Mercer, 1972; Denton et al., 1989; Prentice et al., 1986; Ackert, 2000; Ackert and Kurz, 2004), with Ackert (2000) describing the highest landforms – collectively termed “Dominion drift” – as cold-based deposits in which boulders exhibit extreme structural degradation; cavernous weathering is well-developed in dolerite clasts, while sandstone boulders have been destroyed. Cosmogenic 3He ages constraining the Oliver Platform moraine (Dominion drift) range from 1.7 to 4.6 Ma and are included in Fig. 6. Between the Dominion drift and modern surface of Beardmore Glacier, similar yet undated deposits are grouped into three broad units that, on the basis of relative weathering, get progressively younger with decreasing elevation (Mercer, 1972; Denton et al., 1989). Farther afield at the southern end of the TAM range, Bromley et al. (2010) reported at least five distinct cold-based till units alongside Reedy Glacier in the Wisconsin Range (Fig. 1). As at Otway Massif, the distribution of landforms at Quartz Hills, Polygon Spur, and Tillite Spur indicates deposition by north-flowing EAIS ice conforming to the current landscape, while relative weathering characteristics suggest that deposits increase in age with elevation. The highest cold-based tills at Reedy Glacier – “Reedy E” drift – comprise highly deflated surfaces of exfoliated granite debris, into which are set granitic boulders exhibiting extreme cavernous weathering. Cosmogenic 10Be dates constrain the Reedy E deposits to 2.0–7.0 Ma at Quartz Hills, 1.2–6.6 Ma at Polygon Spur, and 1.7–5.2 Ma at Tillite Spur (see Sect. 4). Together, the geomorphologic and weathering characteristics of deposits at Reedy Glacier, Dominion Range, and Roberts Massif are sufficiently similar to those at Otway Massif to permit a first-order regional synthesis (Sect. 4).

3.3 Otway Massif cosmogenic surface-exposure ages

The application of surface-exposure dating to glacial deposits relies on the premise that glacially transported clasts originate from subglacial erosion and thus contain negligible concentrations of cosmogenic nuclides prior to deposition on a moraine ridge or drift surface. Upon exposure to the cosmic ray flux, nuclide accumulation begins within the lattices of constituent minerals; concentrations of cosmogenic 3He, 10Be, and 21Ne in glacial erratics thus yield exposure ages for the final occupation of the moraine or the deglaciation of a land surface. Including replicates, the new dataset from Otway Massif comprises 80 measurements of cosmogenic 3He in samples from 52 boulders located on the crests of five moraine ridges (Mogul, Dutch, Joshua, Montana, Charlie) and perched on two drift surfaces (Old, Upper).

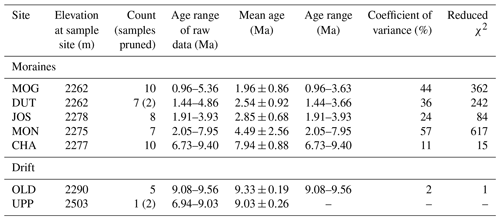

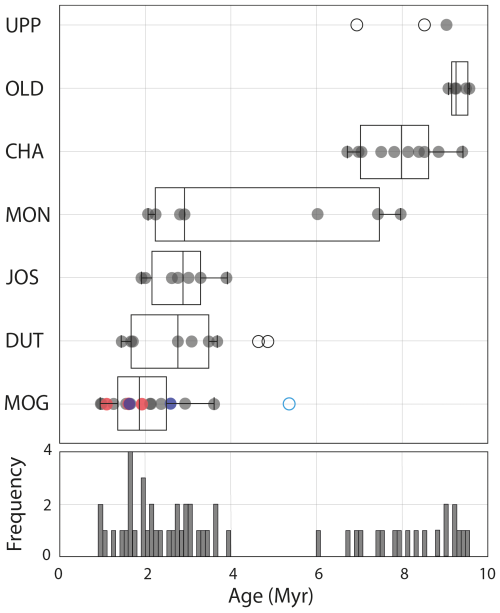

Individual ages are given in Table S1 in the Supplement and calculated landform ages in Table 1. Complete step-degassing results and nuclide concentrations are given in Tables S2–S4; all boulder information and metadata are archived online in the ICE-D:ANTARCTICA database (https://www.ice-d.org/antarctica/, last access: 17 January 2025). To resolve likely depositional ages for individual units and landforms, we measured at least three (and typically more than five) samples per feature in order to perform statistics on each population. Specifically, we employed the coupled statistical stratigraphic protocol detailed by Balter-Kennedy et al. (2020) to identify outlier samples: assuming that a moraine's true age lies within the range of measured exposure ages from that landform, any exposure age on a moraine that is older (younger) than all exposure ages on a stratigraphically older (younger) landform is deemed erroneous and rejected (Balter-Kennedy et al., 2020). We also pruned as likely geomorphic outliers any samples returning ages > 2σ beyond the main age population of that moraine. While the Otway dataset as a whole includes few outliers under this elimination method, we note that this primarily reflects the broad and/or non-normal distributions of many of the moraines studied. Indeed, recognising that some landforms exhibit relatively tight distributions (i.e. Charlie moraine and Old drift), the majority of dated landforms at Otway Massif exhibit sufficient scatter (coefficient of variance > 15 %) to warrant using the range as the most conservative and best estimate of deposition age. Since production rate uncertainty is minor by comparison to the range of exposure ages for any given moraine, we do not consider this in our treatment of the chronology. All ages are shown as box plots in Fig. 4.

Figure 4Box plots illustrating the surface-exposure ages for the Plio-Pleistocene moraines and drift units preserved at Otway Massif. Units are arranged stratigraphically, with names corresponding to those given in Fig. 2. Filled grey, pink, and blue circles denote 3He, 10Be, and 21Ne ages, respectively; empty circles denote outliers, with colours corresponding to nuclide. Mean landform or unit age is shown by the red crosses. The histogram panel depicts all apparent exposure ages from Otway Massif and illustrates the potential hiatus in deposition discussed in Sect. 4.

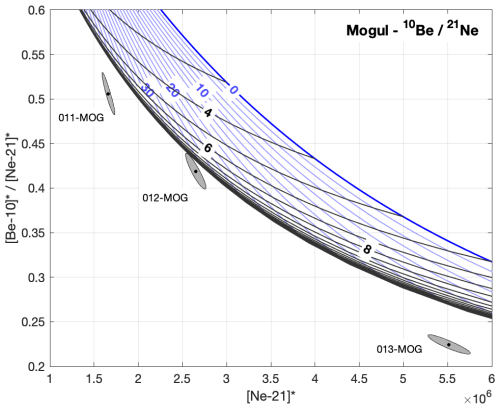

A total of 10 dolerite samples from the crest of the Mogul moraine range in age from 0.98 to 3.63 Ma (Table 1; Figs. 2 and 4), while three small sandstone boulders on the same crest (15-OTW-011, 012, and 013) returned apparent beryllium-10 ages ranging from 1.09 to 1.92 Ma (Table 1; Fig. 4). The same three sandstone samples also gave apparent neon-21 ages ranging from 1.65 to 5.36 Ma (Table 1; Fig. 4). As illustrated in the two-nuclide diagram in Fig. 5, these paired nuclide concentrations plot below the line of simple exposure, indicating that the boulders have experienced either significant post-depositional erosion or a complex exposure history. Because none of the boulders show evidence of substantial weathering (being fresh in appearance and exhibiting only minor surficial alteration; see Sect. 3.1) and their apparent 10Be and 21Ne ages are not significantly younger than the 3He ages of adjacent dolerite boulders (as would result if the less-resistant sandstone clasts experienced greater erosion than the dolerite), we consider the scenario of multiple periods of exposure as the most plausible cause for these complex exposure histories. Recognising that all three sandstone boulders apparently experienced complex exposure, it would nonetheless be incorrect to assume that all 52 dolerite in our dataset must therefore have undergone similarly complex exposure histories: it is not justified statistically to draw such a conclusion based on only three samples, and the source and transport trajectories of sandstone and dolerite boulders at Otway Massif likely differ considerably based on the relative rarity of sandstone outcrops versus dolerite outcrops. Thus, we continue to interpret the 3He data on the basis that the sample set probably includes boulders both with and without inheritance. For the Mogul moraine, we note that these apparently inheritance-influenced measurements on sandstone clasts nonetheless provide a minimum-limiting constraint for the Mogul moraine of ∼1 Myr, in broad agreement with the helium data.

Figure 5The 10Be–21Ne normalised two-nuclide diagram for three sandstone erratics sampled on the Mogul moraine (15-OTW-011, 012, and 013). Numbered black and blue lines are isolines of constant exposure age (Ma) and steady erosion (cm Myr−1), respectively.

Seven samples from boulders on the Dutch moraine return a strongly multimodal distribution, ranging in age from 1.44 to 3.66 Ma (Table 1; Figs. 2 and 4). Two additional samples from this landform (15-OTW-018 and 019) returned ages older than all eight samples from the next stratigraphically older Joshua moraine and thus were excluded as stratigraphic outliers. Farther upslope, eight boulders on the Joshua moraine give a range of 1.91–3.93 Ma, while the Montana moraine dates to 2.05–7.95 Ma (Table 1; Figs. 2 and 4). A total of 10 samples from the Charlie moraine give a relatively tight dataset ranging from 6.73 to 9.40 Ma (Table 1; Figs. 2 and 4), while five boulders embedded in the Old drift surface, within 200 m of the Charlie moraine, provide an internally consistent distribution of 9.08–9.56 Ma (Table 1; Figs. 2 and 4). Finally, at the upper end of our transect and close to the northern flank of Mom Peak, three samples from the Upper drift (Fig. 2) give a bimodal age distribution ranging from 6.94 to 9.03 Ma (Table 1; Fig. 4). Being younger than all five ages from the stratigraphically younger Old drift, we excluded samples 15-OTW-059 and 60 as young outliers. Consequently, our best estimate for the deposition of Upper drift is based on a single age of 9.03±0.26 Ma afforded by sample 15-OTW-58.

The presence of dolerite boulders in the TAM with >10 Ma exposure ages confirms that erosion rates are very low, thus limiting the possible impact of erosion on the younger part of the Otway chronology. Nonetheless, since erosion rates are greater than zero, we sought to evaluate the impact of erosion on our dataset. If we assume that the oldest sample in our record (15-OTW-055) is no older than 14.5 Ma, which is the oldest material reported from neighbouring Roberts Massif (Balter-Kennedy et al., 2020), the erosion rate at our site cannot be greater than 3.3 cm Myr−1. Applying that rate to a sample of mid-Pliocene age (e.g. 15-OTW-026) changes the apparent exposure age from 3 to 3.3 Ma, which is not significant relative to the age ranges exhibited by each moraine reported here. Therefore, we correct our age calculations for erosion.

The glacial geological record from Otway Massif spans the latter half of the Miocene (during which the Charlie, Old, and Upper deposits were emplaced) to at least the middle Pleistocene (i.e. Mogul moraine). Together, the morphology and sedimentology of the Otway glacial deposits, like those described from neighbouring sites (Ackert, 2000; Bader et al., 2017; Balter-Kennedy et al., 2020; Bergelin et al., 2022), are typical of cold-based ablation tills reflecting deposition under glaciologic conditions similar to today. Coupled with the dearth of outwash or fluvial landforms, these glacial geological characteristics indicate that the central TAM have been dominated by a cold, arid climate for the duration of our record, with no evidence for even brief interruptions during that period. This is significant because it requires that the high-elevation Antarctic interior remained a polar desert environment even during the relative warmth of the late Miocene epoch and the subsequent MPWP, as proposed by previous glacial geological research in the central TAM (Barrett, 2013; Bibby et al., 2016; Balter-Kennedy et al., 2020; Spector and Balco, 2021; Bergelin et al., 2022). Our record also provides additional age control for the transition from warm- to cold-based glaciation at Otway Massif. According to our ages from the Old drift, both the shaping of the alpine topography by temperate ice and emplacement of wet-based Sirius Group lodgement tills occurred prior to 9 Ma, a result that is in general agreement with previous minimum estimates from elsewhere in the TAM based upon 40Ar/39Ar ages (Sugden and Denton, 2004, and references therein; Lewis et al., 2006; Smellie et al., 2011) and cosmogenic surface-exposure ages (Bruno et al., 1997; Schäfer et al., 1999; Di Nicola et al., 2012; Balter-Kennedy et al., 2020).

As shown in Figs. 2 and 4, the ages reported here for each drift unit fall broadly in stratigraphic order, becoming increasingly older with distance from the modern EAIS margin. Not only does it support our observations of relative weathering and desert pavement development, this stratigraphic relationship also highlights a persistent first-order pattern of relative ice surface lowering at Otway Massif, which aligns with similar patterns documented elsewhere in the central TAM (Denton et al., 1989; Hagen, 1995; Ackert, 2000; Ackert and Kurz, 2004; Bader et al., 2017; Balter-Kennedy et al., 2020; Bergelin et al., 2022) and southern TAM (Bromley et al., 2010, 2012). Since this process both postdates the end of significant orographic uplift (Fitzgerald, 1994; Miller et al., 2010; He et al., 2021) and is comparatively minor in scale (tens of metres rather than kilometres), we posit that a likely driver is localised isostatic uplift of mountain blocks by selective linear erosion beneath wet-based portions of EAIS outlet glaciers since the mid Miocene (Stern et al., 2005), as described in detail by Balter-Kennedy et al. (2020) for the upper Shackleton Glacier. Fluctuations in the volume of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet (WAIS), into which EAIS outlet glaciers drain during ice ages, may also influence the elevational offset between relict moraines and the modern ice surface at Otway Massif, though the magnitude of that effect diminishes with increasing distance and elevation from the WAIS (Bromley et al., 2010, 2012; Todd et al., 2010). Assuming that the long-term relative drop in ice sheet surface observed in the TAM is unlikely to have been monotonic, it is possible – if not probable – that the Otway moraines have been overridden by the EAIS on multiple occasions, in which case relict moraines might contain material accrued over several glacial cycles. While we cannot test this scenario with the current dataset, such an “accretionary” process might account for at least some of the scatter exhibited by moraines with broad age ranges. In the same vein, the tight age distribution of the higher-elevation Old drift (Table 1; Figs. 2 and 4) might suggest that the EAIS margin only occupied this position once. The absence of this pattern from neighbouring Shackleton Glacier, however, where the lowest and youngest moraines at Roberts Massif give relatively tight age distributions despite the likelihood of repeated overriding (Balter-Kennedy et al., 2020), leads us to infer that the generally broader age distributions at Otway Massif primarily reflect a greater degree of inheritance and/or exhumation at this site.

Beyond the overall stratigraphic coherence of our dataset, we recognise that the age distributions for these glacial landforms are too broad and/or complex to pinpoint the timing of deposition beyond a range. The Mogul moraine, for example, includes 10 ages spanning ∼2.6 Ma, none of which can be rejected as an unequivocal outlier according to our protocol. Assuming that occupation of the Mogul moraine for the entire 2.6 Myr range is unlikely (given the typical duration of Pleistocene glacial maxima), the most plausible explanation for this and other broad distributions is the incorporation of boulders with nuclide concentrations inherited from past periods of exposure, which skews the landform's apparent age towards being anomalously old. In this case, the Mogul moraine's true age would be closer to 1 Ma than to 3.5 Ma, a scenario supported by our use of the three 10Be measurements as maximum-limiting ages (Fig. 4). Yet to simply correlate deposition with the youngest age in a population would ignore the potential influence of geomorphic factors (e.g. burial by snow, erosion, exhumation, or rolling due to moraine slumping) that might affect boulders following deposition and which, along with the addition of younger material during subsequent overriding episodes (see above), can skew the apparent age towards being anomalously young. Therefore, in the absence of obvious physical indicators for either young or old anomalies, we conclude that the accuracy of single-nuclide-based age estimates in cold-based glacial regimes remains poor and that in most instances ranges are the only reliable means for presenting ages.

For the existing TAM dataset generally and the Otway record specifically, this fact presents a challenge to assessments of ice sheet response to climate events such as the MPWP; dated moraines typically yield age ranges exceeding the ∼300 kyr duration of the MPWP, and all Otway moraines overlap with the event within error (Fig. 4), with the exception of the Charlie moraine. The Mogul moraine illustrates this matter well: if we take the young end of the range, the moraine postdates the MPWP by 2 million years, whereas the older end of the range falls squarely within the MPWP. Further, at the neighbouring sites within the central and southern TAM where mean moraine ages fall within the MPWP (e.g. the Reedy E and Oliver Platform moraines), their respective uncertainties remain too great to be comparable with climate events of this scale (Fig. 6). Compounding this issue is uncertainty over (1) the applicability of long-term erosion rates (see Sect. 3.3) and (2) uncertainty in extrapolating production rates inferred from calibration data with 10–100 kyr exposure durations to exposure periods in the 1–10 Ma range. While some constraints (e.g. Balter-Kennedy et al., 2020) indicate that the calibrated production rates are probably accurate over the longer term, it remains challenging to verify this with the available data, highlighting the growing need for production rate calibrations on the continent itself.

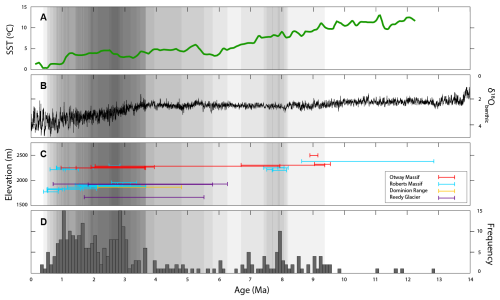

Figure 6Temporal comparison of long-term global climate conditions and frequency of moraine deposition in the central and southern TAM, adapted from Balter-Kennedy et al. (2020) and including additional data from the present study and other published work (Ackert and Kurz, 2004; Bromley et al., 2010). (a) Southern Hemisphere average sea surface temperature reconstructed from alkenones (Herbert et al., 2016); (b) benthic oxygen isotope curve (De Vleeschouwer et al., 2017); (c) moraine age plotted against elevation for landforms at Otway Massif (red circles), Roberts Massif (turquoise circles), Dominion Range (yellow circle), and Reedy Glacier (purple circles); and (d) a histogram depicting all apparent exposure ages (all samples from each of the four TAM locations discussed) shown in panel (c). Grey shading scales with the extent of agreement in moraine ages across different landforms featured in panel (c).

Bounded stratigraphically by the younger Joshua moraine (1.9–3.9 Ma; Figs. 2 and 4) and older Charlie moraine (6.7–9.4 Ma; Figs. 2 and 4), the Montana moraine exhibits both an unusually broad age range (∼6 Myr) and a conspicuous 3 Myr “hiatus” during which there are no ages in our dataset (Fig. 4). From the data on hand and assuming that the Montana moraine represents a single period of deposition, the moraine's true age could equally fall at the older end of the range – as suggested by the strong similarity to Charlie and Old deposits in relative weathering and desert pavement development (see below) – or at the younger end, bringing the Montana moraine closer in age to the Joshua moraine (Fig. 4). There are no data for the intervening ∼3 Myr. Alternatively, recognising that cold-based ice is minimally erosive (passing over landscapes with little or no impact on pre-existing landforms), it is conceivable that the Montana dataset represents not one but multiple periods of deposition at this site, the first during the late Miocene and the second during the Pliocene (see above). When viewing either model, the apparent gap in moraine deposition at Otway Massif is similar to that documented by Balter-Kennedy et al. (2020) at the head of Shackleton Glacier (Figs. 1 and 6), where deposition of the Misery moraines and the next stratigraphically youngest moraine (Ringleader) was separated by ∼3.5 Myr. Together, these datasets raise the possibility that the EAIS margin was absent from the upper TAM for a protracted period (Fig. 4), potentially reflecting a smaller ice sheet at that time. If true, resolving the climatic and/or physical drivers of a reduced EAIS during the late Miocene–early Pliocene, which is not generally viewed as a period of significant warmth or enhanced radiative forcing (Fig. 6), poses a compelling challenge for Antarctic research.

Relict glacial deposits at Otway Massif provide a direct terrestrial record of EAIS behaviour in the central TAM spanning the last ∼9 million years. Coupled with our geomorphic observations, cosmogenic 3He, 21Ne, and 10Be surface-exposure ages from five separate moraine limits and two drift units confirm the presence of a cold-based ice sheet in the upper central TAM since at least the late Miocene and thus add to the growing terrestrial consensus that the transition from temperate to polar climate conditions in Antarctica occurred prior to the late Miocene, as did emplacement of wet-based Sirius Group tills. Gradual lowering of the ice surface relative to Otway Massif over the same period mirrors that observed elsewhere in the TAM and is suggestive of gradual isostatic uplift in response to long-term trough erosion beneath wet-based portions of EAIS outlet glaciers.

According to both the new Otway dataset and our regional synthesis of published moraine ages (Fig. 6), there is no compelling geologic evidence from the central and southern TAM for a significant change in EAIS configuration during the MPWP. While this might signify that interior portions of the ice sheet are perhaps insensitive to the magnitude of climate warming proposed for the middle Pliocene, we (1) caution that the uncertainties associated with this dating method in Antarctica remain too large to capture such short-lived events as the MPWP and (2) highlight that possible episodes of smaller-than-present ice extent cannot be ruled out from the available terrestrial geologic record.

Of potentially greater climatic and glaciologic significance, an apparent gap in moraine deposition between ∼4–7 Ma mirrors the glacial geological record from the head of Shackleton Glacier (Fig. 6) and is not inconsistent with the hypothesis that the ice sheet surface in the central TAM was lower during that period than subsequently. Recognising that this hiatus overlaps broadly with early- to mid-Pliocene episodes of EAIS ice-marginal variability inferred from marine proxies, clear disparities in the timing and duration of the terrestrial and marine events mean these events cannot be correlated using existing data. Nonetheless, the Otway hiatus, if replicated, has clear implications for our understanding of EAIS stability and climate interactions, and thus affords a potentially valuable new target for terrestrial palaeoclimatology.

All data reported here that are not already published elsewhere are available in the Supplement.

The supplement related to this article is available online at: https://doi.org/10.5194/cp-21-145-2025-supplement.

GRMB and GB designed the research. GRMB, GB, MSJ, and HT conducted fieldwork and sample collection. ABK, GB, and GRMB prepared and analysed samples. GRMB and GB wrote the paper with input from all authors.

The contact author has declared that none of the authors has any competing interests.

Publisher's note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims made in the text, published maps, institutional affiliations, or any other geographical representation in this paper. While Copernicus Publications makes every effort to include appropriate place names, the final responsibility lies with the authors.

We thank the United States Antarctic Program and Kenn Borek Air for logistical support, Chris Simmons for field safety support, and Mike Cloutier and the Polar Geospatial Center team for providing all geospatial data. Tim Becker assisted with noble gas measurements at BGC, and Kaj Overturf helped with sample preparation at the University of Maine. We are particularly grateful to Kathy Licht and Robert Ackert, both of whom provided thorough and constructive reviews of an earlier version of this paper. The LLNL portion of this work was carried out under contract no. DE-AC52-07NA27344. This is LLNL-JRNL-861966.

This research was supported by the National Science Foundation, Office of Polar Programs (grants nos. 1443321 (Bromley) and 1443329 (Balco)), including a Research Experiences for Undergraduates (REU) supplement to grant no. 1443321. Additional support was provided by the Ann and Gordon Getty Foundation.

This paper was edited by Ran Feng and reviewed by Kathy Licht, Robert Ackert, and Ran Feng.

Ackert, R. P.: Antarctic glacial chronology: new constraints from surface exposure dating, PhD thesis, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, USA, https://doi.org/10.1575/1912/4123, 2000.

Ackert, R. P. and Kurz, M. D.: Age and uplift rates of Sirius Group sediments in the Dominion Range, Antarctica, from surface exposure dating and geomorphology, Global Planet. Change 42, 207–225, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloplacha.2004.02.001, 2004.

Bader, N. A., Licht, K. J., Kaplan, M. R., Kassab, C., and Winckler, G.: East Antarctic ice sheet stability recorded in a high-elevation ice-cored moraine, Quaternary Sci. Rev., 159, 88–102, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2016.12.005, 2017.

Balco, G. and Shuster, D. L.: Production rate of cosmogenic 21Ne in quartz estimated from 10Be, 26Al, and 21Ne concentrations in slowly eroding Antarctic bedrock surfaces, Earth Planet. Sc. Lett., 281, 48–58, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2009.02.006, 2009.

Balco, G., Stone, J. O., Lifton, N. A., and Dunai, T. J.: A complete and easily accessible means of calculating surface exposure ages or erosion rates from 10Be and 26Al measurements, Quatern. Geochronol., 3, 174–195, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quageo.2007.12.001, 2008.

Balco, G., Blard, P. H., Shuster, D. L., and Stone, J. O. H.: Cosmogenic and nucleogenic 21Ne in quartz in a 28-meter sandstone core from the McMurdo Dry Valleys, Antarctica, Quatern. Geochronol., 52, 63–76, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quageo.2019.02.006, 2019.

Balter-Kennedy, A., Bromley, G., Balco, G., Thomas, H., and Jackson, M. S.: A 14.5-million-year record of East Antarctic Ice Sheet fluctuations from the central Transantarctic Mountains, constrained with cosmogenic 3He, 10Be, 21Ne, and 26Al, The Cryosphere 14, 2647–2672, https://doi.org/10.5194/tc-14-2647-2020, 2020.

Barrett, P. J.: Resolving views on Antarctic Neogene glacial history – The Sirius debate, Earth Environ. Sci. T. Roy. Soc. Edinburgh, 104, 31–53, https://doi.org/10.1017/S175569101300008X, 2013.

Barrett, P. J. and Hambrey, M. J.: Plio-Pleistocene sedimentation in Ferrar Ford, Antarctica, Sedimentology, 39, 109–123, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-3091.1992.tb01025.x, 1992.

Barrett, P. J. and Powell, R. D.: Middle Cenozoic glacial beds at Table Mountain, southern Victoria Land, in: Antarctic geoscience, edited by: Craddock, C., University of Wisconsin Press, Madison, ISBN 0299084108, 1982.

Bart, P. J.: Did the Antarctic ice sheets expand during the early Pliocene?, Geology, 29, 67–70, https://doi.org/10.1130/0091-7613(2001)029<0067:DTAISE>2.0.CO;2, 2001.

Bart, P. J. and Anderson, J. B.: Relative temporal stability of the Antarctic Ice Sheets during the late Neogene based on the maximum frequency of outer shelf grounding events, Earth Planet. Sc. Lett., 182, 259–272, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0012-821X(00)00257-0, 2000.

Bergelin, M., Putkonen, J., Balco, G., Morgan, D., Corbett, L. B., and Bierman, P. R.: Cosmogenic nuclide dating of two stacked ice masses: Ong Valley, Antarctica, The Cryosphere 16, 2793–2817, https://doi.org/10.5194/tc-16-2793-2022, 2022.

Bibby, T., Putkonen, J., Morgan, D., Balco, G., and Shuster, D. L.: Million year old ice found under meter thick debris layer in Antarctica, Geophys. Res. Lett., 43, 6995–7001, https://doi.org/10.1002/2016GL069889, 2016.

Blard, P. H. and Farley, K. A.: The influence of radiogenic 4He on cosmogenic 3He determinations in volcanic olivine and pyroxene, Earth Planet. Sc. Lett., 276, 20–29, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2008.09.003, 2008.

Blard, P. H., Balco, G., Burnard, P. G., Farley, K. A., Fenton, C. R., Friedrich, R., Jull, A. J. T., Niedermann, S., Pik, R., Schaefer, J. M., Scott, E. M., Shuster, D. L., Stuart, F. M., Stute, M., Tibari, B., Winckler, G., and Zimmermann, L.: An interlaboratory comparison of cosmogenic 3He and radiogenic 4He in the CRONUS-P pyroxene standard, Quatern. Geochronol., 26, 11–19, 2015.

Blasco, J., Tabone, I., Moreno-Parada, D., Robinson, A., Alvarez-Solas, J., Pattyn, F., and Montoya, M.: Antarctic tipping points triggered by the mid-Pliocene warm climate, Clim. Past, 20, 1919–1938, https://doi.org/10.5194/cp-20-1919-2024, 2024.

Bockheim, J. G., Wilson, S. C., and Leide, J. E.: Soil development in the Beardmore Glacier region, Antarctica, Antarct. J., 21, 93–95, 1986.

Boening, C., Lebsock, M., Landerer, F., and Stephens, G.: Snowfall-driven mass change on the East Antarctic ice sheet, Geophys. Res. Lett., 39, L21501, https://doi.org/10.1029/2012GL053316, 2012.

Borchers, B., Marrero, S., Balco, G., Caffee, M., Goehring, B., Lifton, N., Nishiizumi, K., Phillips, F., Schaefer, J., and Stone, J.: Geological calibration of spallation production rates in the CRONUS-Earth project, Quatern. Geochronol., 31, 188–198, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quageo.2015.01.009, 2016.

Brancato, V., Rignot, E., Milillo, P., Morlighem, M., Mouginot, J., An, L., Scheuchl, B., Jeong, S., Rizzoli, P., Bueso Bello, J. L., and Prats-Iraola, P.: Grounding line retreat of Denman Glacier, East Antarctica, measured with COSMO-SkyMed radar interferometry data, Geophys. Res. Lett., 47, e2019GL086291, https://doi.org/10.1029/2019GL086291, 2020.

Bromley, G. R. M., Hall, B. L., Stone, J. O., Conway, H., and Todd, C. E.: Late Cenozoic deposits at Reedy Glacier, Transantarctic Mountains: implications for former thickness of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet, Quaternary Sci. Rev., 29, 384–398, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2009.07.001, 2010.

Bromley, G. R., Hall, B. L., Stone, J. O., and Conway, H.: Late Pleistocene evolution of Scott Glacier, southern Transantarctic Mountains: implications for the Antarctic contribution to deglacial sea level, Quaternary Sci. Rev., 50, 1–13, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2012.06.010, 2012.

Bromley, G. R. M., Winckler, G., Schaefer, J. M., Kaplan, M. R., Licht, K. J., and Hall, B. L.: Pyroxene separation by HF leaching and its impact on helium surface-exposure dating, Quatern. Geochronol., 23, 1–8, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quageo.2014.04.003, 2014.

Bruno, A. L., Baur, H., Graf, T., Schlücter, C., Signer, P., and Wieler, R.: Dating of Sirius Group tillites in the Antarctic Dry Valleys with cosmogenic 3He and 21Ne, Earth Planet. Sc. Lett., 147, 37–54, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0012-821X(97)00003-4, 1997.

Budyko, M. I.: The earth's climate: past and future, in: International Geophysics Series, Elsevier, New York, ISBN 978-0-12-139460-8, 1982.

Burke, K. D., Williams, J. W., Chandler, M. A., Haywood, A. M., Lunt, D. J., and Otto-Bliesner, B. L.: Pliocene and Eocene provide best analogs for near-future climates, P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 115, 13288–13293, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1809600115, 2018.

Burton, L. E., Haywood, A. M., Tindall, J. C., Dolan, A. M., Hill, D. J., Abe-Ouchi, A., Chan, W.-L., Chandan, D., Feng, R., Hunter, S. J., Li, X., Peltier, W. R., Tan, N., Stepanek, C., and Zhang, Z.: On the climatic influence of CO2 forcing in the Pliocene, Clim. Past, 19, 747–764, https://doi.org/10.5194/cp-19-747-2023, 2023.

Cook, C. P., Van De Flierdt, T., Williams, T., Hemming, S. R., Iwai, M., Kobayashi, M., Jimenez-Espejo, F. J., Escutia, C., González, J. J., Khim, B. K., and McKay, R. M.: Dynamic behaviour of the East Antarctic ice sheet during Pliocene warmth, Nat. Geosci., 6, 765–769, https://doi.org/10.1038/ngeo1889, 2013.

Cowan, E. A.: Identification of the glacial signal from the Antarctic Peninsula since 3.0 Ma at Site 1101 in a continental rise sediment drift, in: Proceedings of the Ocean Drilling Program, Scientific Results 178, edited by: Barker, P. F., Camerlenghi, A., Acton, G. D., and Ramsey, A. T. S., http://www-odp.tamu.edu/publications/178_SR/chap_10/chap_10.htm (last access: 17 January 2025), 2002.

Davis, C. H., Li, Y., McConnell, J. R., Frey, M. M., and Hanna, E.: Snowfall-driven growth in East Antarctic ice sheet mitigates recent sea-level rise, Science, 308, 1898–1901, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1110662, 2005.

DeConto, R. M. and Pollard, D.: Contribution of Antarctica to past and future sea-level rise, Nature, 531, 591–597, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature17145, 2016.

Denton, G. H., Prentice, M. L., Kellogg, D. E., and Kellogg, T. B.: Late Tertiary history of the Antarctic ice sheet: Evidence from the Dry Valleys, Geology, 12, 263–267, https://doi.org/10.1130/0091-7613(1984)12<263:LTHOTA>2.0.CO;2, 1984.

Denton, G. H., Bockheim, J. G., Wilson, S. C., and Leide, J. E.: Late Quaternary ice-surface fluctuations of Beardmore Glacier, Transantarctic Mountains, Quatern. Res., 31, 183–209, https://doi.org/10.1016/0033-5894(89)90005-7, 1989.

Denton, G. H., Sugden, D. E., Marchant, D. R., Hall, B. L., and Wilch, T. I.: East Antarctic Ice Sheet sensitivity to Pliocene climate change from a Dry Valleys perspective, Geogr. Ann. A, 75, 155–204, https://doi.org/10.1080/04353676.1993.11880393, 1993.

De Vleeschouwer, D., Vahlenkamp, M., Crucifix, M., and Pälike, H.: Alternating Southern and Northern Hemisphere climate response to astronomical forcing during the past 35 m.y., Geology, 45, 375–378, https://doi.org/10.1130/G38663.1, 2017.

Di Nicola, L., Baroni, C., Strasky, S., Salvatore, M. C., Schlüchter, C., Akçar, N., Kubik, P. W., and Wieler, R.: Multiple cosmogenic nuclides document the stability of the East Antarctic Ice Sheet in northern Victoria Land since the Late Miocene (5–7 Ma), Quaternary Sci. Rev., 57, 85–94, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2012.09.026, 2012.

Dowsett, H. J. and Cronin, T. M.: High eustatic sea level during the middle Pliocene: Evidence from the southeastern U.S. Atlantic coastal plain, Geology, 18, 435–438, https://doi.org/10.1130/0091-7613(1990)018<0435:HESLDT>2.3.CO;2, 1990.

Dowsett, H., Robinson, M., and Foley, K.: Pliocene three-dimensional global ocean temperature reconstruction, Clim. Past 5, 769–783, https://doi.org/10.5194/cp-5-769-2009, 2009.

Dowsett, H., Dolan, A., Rowley, D., Moucha, R., Forte, A. M., Mitrovica, J. X., Pound, M., Salzmann, U., Robinson, M., Chandler, M., and Foley, K.: The PRISM4 (mid-Piacenzian) paleoenvironmental reconstruction, Clim. Past, 12, 1519–1538, https://doi.org/10.5194/cp-12-1519-2016, 2016.

Dragone, N. B., Diaz, M. A., Hogg, I. D., Lyons, W. B., Jackson, W. A., Wall, D. H., Adams, B. J., and Fierer, N.: Exploring the boundaries of microbial habitability in soil, J. Geophys. Res.-Biogeo., 126, e2020JG006052, https://doi.org/10.1029/2020JG006052, 2021.

Dumitru, O. A., Austermann, J., Polyak, V. J., Fornós, J. J., Asmerom, Y., Ginés, J., Ginés, A., and Onac, B. P.: Constraints on global mean sea level during Pliocene warmth, Nature, 574, 233–236, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-019-1543-2, 2019.

Fitzgerald, P. G.: Thermochronologic constraints on post-Paleozoic tectonic evolution of the central Transantarctic Mountains, Antarctica, Tectonics, 13, 818–836, https://doi.org/10.1029/94TC00595, 1994.

Golledge, N. R., Kowalewski, D. E., Naish, T. R., Levy, R. H., Fogwill, C. J., and Gasson, E. G.: The multi-millennial Antarctic commitment to future sea-level rise, Nature, 526, 421–425, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature15706, 2015.

Gregory, J. M. and Huybrechts, P.: Ice-sheet contributions to future sea-level change, Philos. T. Roy. Soc. A,364, 1709–1732, https://doi.org/10.1098/rsta.2006.1796, 2006.

Hagen, E. H.: A geochemical and petrological investigation of meteorite ablation products in till and ice of Antarctica, Unpublished PhD thesis, The Ohio State University, https://www.proquest.com/openview/f671b2810060353a923c584227667c34/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=18750&diss=y (last access: 17 January 2025), 1995.

Hambrey, M. J. and McKelvey, B.: Major Neogene fluctuations of the East Antarctic ice sheet: Stratigraphic evidence from the Lambert Glacier region, Geology, 28, 887–890, https://doi.org/10.1130/0091-7613(2000)28<887:MNFOTE>2.0.CO;2, 2000.

Haywood, A. M., Hill, D. J., Dolan, A. M., Otto-Bliesner, B. L., Bragg, F., Chan, W. L., Chandler, M. A., Contoux, C., Dowsett, H. J., Jost, A., and Kamae, Y.: Large-scale features of Pliocene climate: results from the Pliocene Model Intercomparison Project, Clim. Past, 9, 191–209, https://doi.org/10.5194/cp-9-191-2013, 2013.

Haywood, A. M., Tindall, J. C., Dowsett, H. J., Dolan, A. M., Foley, K. M., Hunter, S. J., Hill, D. J., Chan, W.-L., Abe-Ouchi, A., Stepanek, C., Lohmann, G., Chandan, D., Peltier, W. R., Tan, N., Contoux, C., Ramstein, G., Li, X., Zhang, Z., Guo, C., Nisancioglu, K. H., Zhang, Q., Li, Q., Kamae, Y., Chandler, M. A., Sohl, L. E., Otto-Bliesner, B. L., Feng, R., Brady, E. C., von der Heydt, A. S., Baatsen, M. L. J., and Lunt, D. J.: The Pliocene Model Intercomparison Project Phase 2: large-scale climate features and climate sensitivity, Clim. Past, 16, 2095–2123, https://doi.org/10.5194/cp-16-2095-2020, 2020.

Hearty, P. J., Kindler, P., Cheng, H., and Edwards, R. L.: A +20 m middle Pleistocene sea-level highstand (Bermuda and the Bahamas) due to partial collapse of Antarctic ice, Geology, 27, 375–378, https://doi.org/10.1130/0091-7613(1999)027<0375:AMMPSL>2.3.CO;2, 1999.

Herbert, T. D., Lawrence, K. T., Tzanova, A., Peterson, L. C., Caballero-Gill, R., and Kelly, C. S.: Late Miocene global cooling and the rise of modern ecosystems, Nat. Geosci., 9, 843–847, https://doi.org/10.1038/ngeo2813, 2016.

Higgins, S. M., Denton, G. H., and Hendy, C. H.: Glacial geomorphology of Bonney Drift, Taylor Valley, Antarctica, Geogr. Ann. A, 82, 365–389, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0435-3676.2000.00129.x, 2000.

Hill, D. J., Haywood, A. M., Hindmarsh, R. C. A., and Valdes, P. J.: Characterizing ice sheets during the Pliocene: evidence from data and models, Geological Society London, https://doi.org/10.1144/TMS002.24, 2007.

He, J., Thomson, S. N., Reiners, P. W., Hemming, S. R., and Licht, K. J.: Rapid erosion of the central Transantarctic Mountains at the Eocene-Oligocene transition: Evidence from skewed (U-Th)/He date distributions near Beardmore Glacier, Earth Planet. Sc. Lett., 567, 117009, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2021.117009, 2021.

Huybrechts, P.: West-side story of Antarctic ice, Nature, 458, 295–296, https://doi.org/10.1038/458295a, 2009.

Kaplan, M. R., Licht, K. J.,Winckler, G., Schaefer, J. M., Bader, N., Mathieson, C., Roberts, M., Kassab, C. M., Schwartz, R., and Graly, J. A.: Middle to Late Pleistocene stability of the central East Antarctic Ice Sheet at the head of Law Glacier, Geology, 45, 963–966, https://doi.org/10.1130/G39189.1, 2017.

King, M. A., Bingham, R. J., Moore, P., Whitehouse, P. L., Bentley, M. J., and Milne, G. A.: Lower satellite-gravimetry estimates of Antarctic sea-level contribution, Nature, 491, 586–589, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature11621, 2012.

Kober, F., Alfimov, V., Ivy-Ochs, S., Kubik, P. W., and Wieler, R.: The cosmogenic 21Ne production rate in quartz evaluated on a large set of existing 21Ne-10Be data, Earth Planet. Sc. Lett., 302, 163–171, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2010.12.008, 2011.

Konrad, H., Shepherd, A., Gilbert, L., Hogg, A. E., McMillan, M., Muir, A., and Slater, T.: Net retreat of Antarctic glacier grounding lines, Nat. Geosci., 11, 258–262, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41561-018-0082-z, 2018.

Levermann, A., Clark, P. U., Marzeion, B., Milne, G. A., Pollard, D., Radic, V., and Robinson, A.: The multimillennial sea-level commitment of global warming, P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 110, 13745–13750, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1219414110, 2013.

Lewis, A. R., Marchant, D. R., Kowalewski, D. E., Baldwin, S. L., and Webb, L. E.: The age and origin of the Labyrinth, western Dry Valleys, Antarctica: Evidence for extensive middle Miocene subglacial floods and freshwater discharge to the Southern Ocean, Geology, 34, 513–516, https://doi.org/10.1130/G22145.1, 2006.

Li, X., Rignot, E., Morlighem, M., Mouginot, J., and Scheuchl, B.: Grounding line retreat of Totten Glacier, east Antarctica, 1996 to 2013, Geophys. Res. Lett., 42, 8049–8056, https://doi.org/10.1002/2015GL065701, 2015.

Lifton, N., Sato, T., and Dunai, T. J.: Scaling in situ cosmogenic nuclide production rates using analytical approximations to atmospheric cosmic-ray fluxes, Earth Planet. Sc. Lett., 386, 149–160, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2013.10.052, 2014.

Lunt, D. J., Haywood, A. M., Schmidt, G. A., Salzmann, U., Valdes, P. J., and Dowsett, H. J.: Earth system sensitivity inferred from Pliocene modelling and data, Nat. Geosci., 3, 60–64, https://doi.org/10.1038/ngeo706, 2010.

Mahood, A. D. and Barron, J. A.: Late Pliocene diatoms in a diatomite from Prydz Bay, East Antarctica, Micropaleontology, 42, 285–302, https://doi.org/10.2307/1485876, 1996.

Marchant, D. R. and Denton, G. H.: Miocene and Pliocene paleoclimate of the Dry Valleys region, southern Victoria Land: A geomorphological approach, Mar. Micropaleontol., 27, 253–271, https://doi.org/10.1016/0377-8398(95)00065-8, 1996.

Marchant, D. R., Denton, G. H., and Swisher, C. C.: Miocene-Pliocene-Pleistocene history of Arena Valley, Quatermain Mountains, Antarctica, Geogr. Ann. A, 75, 269–302, https://doi.org/10.1080/04353676.1993.11880397, 1993.

Marchant, D. R., Denton, G. H., Swisher, C. C., and Potter, N.: Late-Cenozoic Antarctic palaeoclimate reconstructed from volcanic ashes in the Dry Valleys region of Southern Victoria Land, Geol. Soc. Am. Bull., 108, 181–194, https://doi.org/10.1130/0016-7606(1996)108<0181:LCAPRF>2.3.CO;2, 1996.

Margerison, H. R., Phillips, W. M., Stuart, F. M., and Sugden, D. E.: Cosmogenic 3He concentrations in ancient flood deposits from the Coombs Hills, northern Dry Valleys, East Antarctica: Interpreting exposure ages and erosion rates, Earth Planet. Sc. Lett., 230, 163–175, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2004.11.007, 2005.

Mayewski, P. A.: Glacial Geology and Late Cenozoic History of the Transantarctic Mountains, Antarctica, Institute of Polar Studies Report, 1–168, Institute of Polar Studies, 1975.

McClymont, E. L., Ford, H. L., Ho, S. L., Tindall, J. C., Haywood, A. M., Alonso-Garcia, M., Bailey, I., Berke, M. A., Littler, K., Patterson, M. O., Petrick, B., Peterse, F., Ravelo, A. C., Risebrobakken, B., De Schepper, S., Swann, G. E. A., Thirumalai, K., Tierney, J. E., van der Weijst, C., White, S., Abe-Ouchi, A., Baatsen, M. L. J., Brady, E. C., Chan, W.-L., Chandan, D., Feng, R., Guo, C., von der Heydt, A. S., Hunter, S., Li, X., Lohmann, G., Nisancioglu, K. H., Otto-Bliesner, B. L., Peltier, W. R., Stepanek, C., and Zhang, Z.: Lessons from a high-CO2 world: an ocean view from ∼3 million years ago, Clim. Past, 16, 1599–1615, https://doi.org/10.5194/cp-16-1599-2020, 2020.

McKay, R., Browne, G., Carter, L., Cowan, E., Dunbar, G., Krissek, L., Naish, T., Powell, R., Reedy, J., Talarico, F., and Wilch, T.: The stratigraphic signature of the late Cenozoic Antarctic Ice Sheets in the Ross Embayment, Geol. Soc. Am. Bull., 121, 1537–1561, https://doi.org/10.1130/B26540.1, 2009.

McKelvey, B. C., Webb, P. N., and Marin, P. C. G.: The Dominion Range Sirius Group: A record of the late Pliocene-early Pleistocene Beardmore Glacier, in: Geological evolution of Antarctica, edited by: Thomson, M. R. A., Crame, J. A., and Thomson, J. W., Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, ISBN 9780521188906, 1991.

Mercer, J. H.: Glacial geology of the Reedy Glacier area, Antarctica, Geol. Soc. Am. Bull., 79, 471–486, https://doi.org/10.1130/0016-7606(1968)79[471:GGOTRG]2.0.CO;2, 1968.

Mercer, J. H.: Some observations on the glacial geology of the Beardmore Glacier area, in: Antarctic geology and geophysics, edited by: Adie, R. J., Universitetsforlaget, Oslo, 427–433, ISBN 10:8200022536, 1972.

Miller, K. G., Wright, J. D., Browning, J. V., Kulpecz, A., Kominz, M., Naish, T. R., Cramer, B. S., Rosenthal, Y., Peltier, W. R., and Sosdian, S.: High tide of the warm Pliocene: Implications of global sea level for Antarctic deglaciation, Geology, 40, 407–410, https://doi.org/10.1130/G32869.1, 2012.

Miller, K. G., Browning, J. V., Schmelz, W. J., Kopp, R. E., Mountain, G. S., and Wright, J.D.: Cenozoic sea-level and cryospheric evolution from deep-sea geochemical and continental margin records, Sci. Adv., 6, eaaz1346, https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aaz1346, 2020.

Miller, S. R., Fitzgerald, P. G., and Baldwin, S. L.: Cenozoic range-front faulting and development of the Transantarctic Mountains near Cape Surprise, Antarctica: Thermochronologic and geomorphologic constraints, Tectonics, 29, 1–21, https://doi.org/10.1029/2009TC002457, 2010.

Naish, T., Powell, R., Levy, R., Wilson, G., Scherer, R., Talarico, F., Krissek, L., Niessen, F., Pompilio, M., Wilson, T., Carter, L., DeConto, R., huybers, P., McKay, R., Pollard, D., Ross, J., Winter, D., Barrett, P., Browne, G., Cody, R., Cowan, E., Crampton, J., Dunbar, G., Dunbar, N., Florindo, F., Gebhardt, C., Graham, I., Hannah, M., Hansaraj, D., Harwood, D., Helling, D., Henrys, S., Hinnov, L., Kuhn, G., Kyle, P., Laufer, A., Maffioli, P., Magens, D., Mandernack, K., McIntosh, W., Millan, C., Morin, R., Ohneisser, C., Paulsen, T., Persico, D., Raine, I., Reed, J., Riesselman, C., Sagnotti, L., Schmitt, D., Sjunneskog, C., Strong, P., Taviani, M., Vogel, S., Wilch, T., and Williams, T.: Obliquity-paced Pliocene West Antarctic ice sheet oscillations, Nature 458, 322–329, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature07867, 2009.

Nishiizumi, K., Imamura, M., Caffee, M. W., Southon, J. R., Finkel, R. C., and McAninch, J.: Absolute calibration of 10Be AMS standards, Nucl. Instrum. Meth. B, 258, 403–413, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nimb.2007.01.297, 2007.

Noble, T. L., Rohling, E. J., Aitken, A. R. A., Bostock, H. C., Chase, Z., Gomez, N., Jong, L. M., King, M. A., Mackintosh, A. N., McCormack, F. S., and McKay, R. M.: The sensitivity of the Antarctic ice sheet to a changing climate: Past, present, and future, Rev. Geophys., 58, e2019RG000663, https://doi.org/10.1029/2019RG000663, 2020.

Pierce, E. L., Williams, T., van de Flierdt, T., Hemming, S. R., Goldstein, S. L., and Brachfeld, S. A.: Characterizing the sediment provenance of East Antarctica's weak underbelly: The Aurora and Wilkes sub-glacial basins, Paleoceanography, 26, PA4217, https://doi.org/10.1029/2011PA002127, 2011.

Prentice, M. L., Denton, G. H., Lowell, T. V., Conway, H. C., and Heusser, L. E.: Pre-late Quaternary glaciation of the Beardmore Glacier region, Antarctica, Antarc. J., 21, 95–98, 1986.

Quilty, P. G., Lirio, J. M., and Jillet, D.: Stratigraphy of the Pliocene Sørsdal Formation, Marine Plain, Vestfold Hills, East Antarctica, Antarct. Sci., 12, 205–216, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954102000000262, 2000.

Rapley, C.: The Antarctic ice sheet and sea level rise, in: Avoiding dangerous climate change, Cambridge University Press, 25–28, ISBN 13 978-0-521-86471-8, 2006.

Raymo, M. E., Lisiecki, L. E., and Nisancioglu, K. H.: Plio-Pleistocene ice volume, Antarctica climate, and the global δ18O record, Science, 313, 492–495, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1123296, 2006.

Richards, F. D., Coulson, S., Hoggard, M., Austermann, J., Dyer, B., and Mitrovica, J.X .: Correcting for mantle dynamics reconciles Mid Pliocene sea-level estimates, EarthArXiv [preprint], https://doi.org/10.31223/X5Z652, 2022.

Rintoul, S. R., Silvano, A., Pena-Molino, B., van Wijk, E., Rosenberg, M., Greenbaum, J. S., and Blankenship, D. D.: Ocean heat drives rapid basal melt of the Totten Ice Shelf, Sci. Adv., 2, e1601610, https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.1601610, 2016.

Rovere, A., Raymo, M. E., Mitrovica, J. X., Hearty, P. J., O'Leary, M. J., and Inglis, J. D.: The Mid-Pliocene sea-level conundrum: glacial isostasy, eustasy and dynamic topography, Earth Planet. Sc. Lett., 387, 27–33, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2013.10.030, 2014.

Schäfer, J. M., Ivy-Ochs, S., Wieler, R., Leya, I., Baur, H., Denton, G. H., and Schlüchter, C.: Cosmogenic noble gas studies in the oldest landscape on earth: surface exposure ages of the Dry Valleys, Antarctica, Earth Planet. Sc. Lett., 167, 215–226, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0012-821X(99)00029-1, 1999.

Schaefer, J. M., Denton, G. H., Kaplan, M., Putnam, A., Finkel, R. C., Barrell, D. J. A., Andersen, B. G., Schwartz, R., Mackintosh, A., Chinn, T., and Schlüchter, C.: High frequency Holocene glacier fluctuations in New Zealand differ from the northern signature, Science, 324, 622–625, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1169312, 2009.

Scherer, R., Hannah, M., Maffioli, P., Persico, D., Sjunneskog, C., Strong, C. P., Taviani, C. P., Winter, D., and the ANDRILL-MIS Science Team: Palaeontologic characterisation and analysis of the AND-1B core, ANDRILL McMurdo Ice Shelf Project, Antarctica, Terra Ant., 14, 223–254, 2007.

Smellie, J. L., Rocchi, S., Gemelli, M., Di Vincenzo, G., and Armienti, P.: A thin predominantly cold-based Late Miocene East Antarctic ice sheet inferred from glaciovolcanic sequences in northern Victoria Land, Antarctica, Palaeogeogr. Palaeocl., 307, 129–149, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.palaeo.2011.05.008, 2011.

Spector, P. and Balco, G.: Exposure-age data from across Antarctica reveal mid-Miocene establishment of polar desert climate, Geology, 49, 91–95, https://doi.org/10.1130/G47783.1, 2021.

Stern, T. A., Baxter, A. K., and Barrett, P. J.: Isostatic rebound due to glacial erosion within the Transantarctic Mountains, Geology, 33, 221–224, https://doi.org/10.1130/G21068.1, 2005.

Stokes, C. R., Abram, N. J., Bentley, M. J., Edwards, T. L., England, M. H., Foppert, A., Jamieson, S. S., Jones, R. S., King, M. A., Lenaerts, J. T., and Medley, B.: Response of the East Antarctic Ice Sheet to past and future climate change, Nature, 608, 275–286, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-022-04946-0, 2022.

Stone, J. O.: Air pressure and cosmogenic isotope production, J. Geophys. Res.-Solid, 105, 23753–23759, https://doi.org/10.1029/2000JB900181, 2000.

Sugden, D. and Denton, G.: Cenozoic landscape evolution of the Convoy Range to Mackay Glacier area, Transantarctic Mountains: Onshore to offshore synthesis, Geol. Soc. Am. Bull., 116, 840–857, https://doi.org/10.1130/B25356.1, 2004.

Sugden, D. E., Denton, G. H., and Marchant, D.: Landscape evolution of the Dry Valleys, Transantarctic Mountains: Tectonic implications, J. Geophys. Res.-Solid, 100, 9949–9967, https://doi.org/10.1029/94JB02895, 1995.

Tauxe, L., Sugisaki, S., Jiménez-Espejo, F., Escutia, C., Cook, C. P., van de Flierdt, T., and Iwai, M.: Geology of the Wilkes land sub-basin and stability of the East Antarctic Ice Sheet: Insights from rock magnetism at IODP Site U1361, Earth Planet. Sc. Lett., 412, 61–69, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2014.12.034, 2015.

The IMBIE Team, Shepherd, A., Ivins, E., Rignot, E., Smith, B., Van Den Broeke, M., and Wouters, B.: Mass balance of the Antarctic Ice Sheet from 1992 to 2017, Nature, 558, 219–222, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-018-0179-y, 2018.

Todd, C., Stone, J., Conway, H., Hall, B., and Bromley, G.: Late Quaternary evolution of Reedy Glacier, Antarctica, Quaternary Sci. Rev., 29, 1328–1341, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2010.02.001, 2010.

Valletta, R. D., Willenbring, J. K., Passchier, S., and Elmi, C.: ratios reflect Antarctic Ice Sheet freshwater discharge during Pliocene warming, Paleoceanogr. Paleocl., 33, 934–944, https://doi.org/10.1029/2017PA003283, 2018.

Webb, P.-N., Harwood, D. M., McKelvey, B. C., Mercer, J. H., and Stott, L. D.: Cenozoic marine sedimentation and ice volume variation in the East Antarctic craton, Geology, 12, 287–291, https://doi.org/10.1130/0091-7613(1984)12<287:CMSAIV>2.0.CO;2, 1984.