the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Documentary evidence of droughts in Sweden between the Middle Ages and ca. 1800 CE

Lotta Leijonhufvud

Dag Retsö

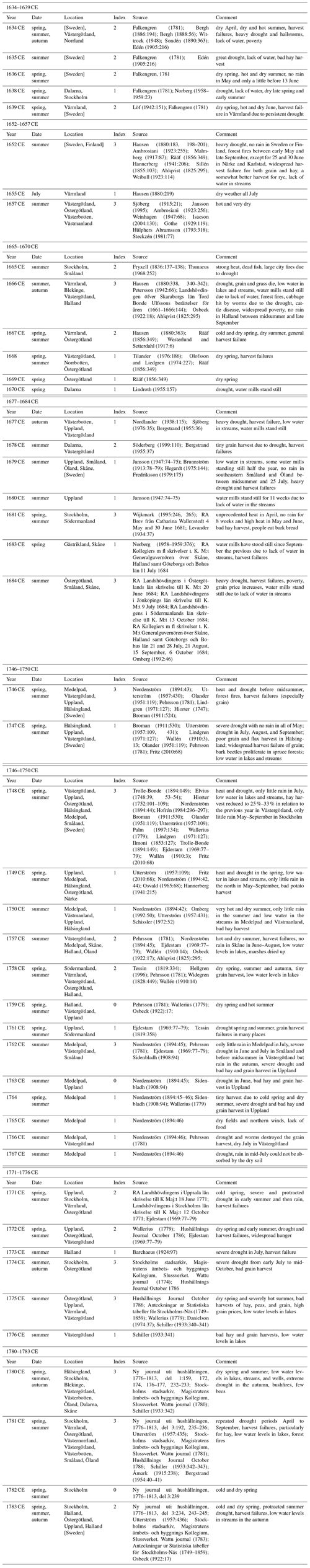

This article explores documentary evidence of droughts in Sweden in the pre-instrumental period (1400–1800 CE). A database has been developed using contemporary sources, such as private and official correspondence letters, diaries, almanac notes, manorial accounts, and weather data compilations. The primary purpose is to utilize hitherto unused documentary data as an input for an index that can be useful for comparisons on a larger European scale.

The survey shows that eight subperiods can be considered as having been particularly struck by summer droughts, causing concomitant harvest failures and having great social impacts in Sweden. This is the case with 1634–1639, 1652–1657, 1665–1670, 1677–1684, 1746–1750, 1757–1767, 1771–1776, and 1780–1783 CE. Within these subperiods, 1652 and 1657 stand out as particularly troublesome years. A number of data for dry summers are also found for the middle decades of the 15th century, the first decade of the 1500s, and the 1550s.

- Article

(432 KB) - Full-text XML

- BibTeX

- EndNote

The purpose of this paper is to present documentary evidence of drought in Sweden for the period 1400 to 1800 CE. For this purpose, a drought index has been constructed. We also try to present a link between instrumental data from precipitation and temperature to our drought index. Is it possible to distinguish periods of drought in Sweden through documentary sources dating from the 15th to the 18th century?

Stretching from 55 to 69∘ N, Sweden is characterized by Arctic climate in the extreme north and temperate climate in the south. Located between the Baltic Sea and the Scandian mountain range, wet weather from the Atlantic affects the western part of Sweden, while the eastern part is protected both by the Scandian mountain range and highland in the south, rendering average precipitation in the eastern part between 300 and 700 mm yr−1, compared to western part that ranges between 800 and 1200 mm yr−1. The length of the winter and the length of the growing period, which vary in the north–south direction, have the most distinct effect on agricultural production and society in general. However, the early modern history of Sweden gives evidence of repeated periods of severe droughts.

In general, drought at the latitude of Sweden is caused by deficient precipitation and only occasionally by excessive temperature and evapotranspiration. Sometimes several meteorological and hydrological factors do combine to produce severe drought with serious socioeconomic consequences. For example, apart from deficiency in precipitation (meteorological drought), seasonal lack of streaming water can also be the result of late spring or low summer temperatures in the Scandian mountain range when snow fail to melt at a normal pace, resulting in insufficient discharge into the rivers producing streamflow (hydrological) droughts and/or low flows (Hisdal and Tallaksen, 2000). Insufficient spring floods are also partly responsible for failed harvests of hay grown in wet meadows and (in historical times) concomitant raised cattle mortality. Conversely, low water levels in streams due to dry autumn and summer weather facilitate quick freezing in the early winter and imply further obstacles to running water mills. Therefore, in the long run droughts do affect agriculture but strike more directly at industrial activities depending on water power. Socioeconomically this has had serious consequences for Sweden, which has been dependent to a large degree on mining and exports of iron and copper, especially from the 17th century onwards.

The indices used in this paper have been constructed from a database launched by Johan Söderberg of the Department of Economic History and International Relations at Stockholm University, to which both authors of this paper have also contributed through adding weather information by excerpting original data from letters, chronicles, newspapers, etc. The database consists of a wide variety of documentary sources: diaries, official letters, and chronicles, in addition to published articles in papers from the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences and early newspapers. This database is available to the public through the Bolin Centre and has some 20 000 entries from 1500 to 1870 CE (https://snd.gu.se/en/catalogue/study/snd1216, last access: 12 September 2021).

A typical statement of a severe drought is found in the diary of the parish priest Petrus Magnii Gyllenius, who also made summarized descriptions of entire years in the province of Värmland. For the year 1652 CE he writes the following statement (our translation):

In the beginning of May it rained a little. Then there was a great drought, this year was called the Great Drought Year. No rain fell, neither in Sweden or Finland, between early May and late September, with the exception of 25 June when a thunderstorm occurred over Letstigen in [the province of] Närke, as and 30 June when it rained a little in Karlstad. In Sweden there was a quite great harvest failure this year for grain due to the severe drought and heat. The drought destroyed the grain in many places, so that nothing was saved of the spring seed, and there were dear times. At the same time there was little hay […] Forest fires caused great damages in Sweden and Finland. Bridges and hay barns burned (Hausen, 1880:198–201).

In this study we have used homogenized historical instrumental temperature data from Stockholm observatory beginning in 1756 and precipitation data from 1786 onwards. The first thing we wanted to do was to examine whether there was any relationship between precipitation (and drought) and temperature, as precipitation data before 1859 CE seem more unreliable than after that year: the data are not represented with decimals, and correlation coefficients between precipitation and temperature become non-existent. Precipitation data before 1893 CE also exhibit severe undercatch problems (Moberg et al., 2003:1501). Moberg et al. (2003) adjust precipitation data with different factors, which we have not done as our focus is the drought index and the kind of factor-increasing adjustments done there will have no effect on correlation coefficients.

In this article, we have used a seven-point index scale (−3, −2, −1, 0, +1, +2, +3) ranging from exceptionally wet (−3) to exceptionally dry (+3). The annual indices from documentary data have been based on the stated intensity of the drought event and its spatial extension. The data are derived from the snow-free season of the year (spring–summer–autumn), which varies in length between March–November in the south and April–October further north. It has only been possible to construct reliable indices for the 16th, 17th, and 18th centuries as no continuous time series can be reconstructed before that due to insufficient amounts of documentary records. Nevertheless, an overview of documentary data from the 15th century will be given.

For some years the documentary data are too contradictory to enable any definite conclusions. In some cases, it derives from regional variations. One example is from 1554, when there was “severe drought” in the province of Uppland, but the same time there was a good harvest in Kronoberg province further to the south (Forssell, 1884, Appendix A:161). But even when data are relatively plentiful, they can be contradictory. One such example is the year 1733. Some data from that year speak of an “unusual” drought in the provinces of Västergötland in the west, and Hälsingland and Dalarna further to the north in May (Broman, 1911; Olofsson and Liedgren, 1974:261). In a period of 18 weeks between early March and the end of June only three short showers of rain are said to have fallen in Västergötland, a province with typically humid weather conditions, and the water level of Lake Vänern was quite low (Bergstrand, 1934:196; Wallén, 1910:13). At the same time, the harvests were good in general in Sweden, and there are no reports of harvest failures (Utterström, 1957:429). In Västergötland itself, the harvest was even said to have been plentiful (Olander, 1951:119). The explanation for this discrepancy may be different timings of sowing of different crops, where, e.g., early maturing crops like barley and wheat (the latter of which was cultivated in Sweden only to a small degree before the 19th century) (Söderberg and Myrdal, 2002) suffered most and crops with a long growing season, like rye and buckwheat, could survive. There is no case where there is evidence of droughts covering the entire growing season, which means that no generalized nutritional catastrophe has been registered. A mitigating factor was that periodically local demand for foodstuffs was reduced through the absence of a large part of the male population, who were participating in the numerous wars Sweden fought in Europe between 1563 and 1718 CE. The most important part of the present analysis is the construction of an index. The construction was made comprehensively so that instances of drought or precipitation were evaluated within the context of the database.

As has been said, documentary data for the 15th and 16th centuries are scarce, uneven, and spread out in a number of different source categories. Therefore, no attempt has been made to derive any drought index values before 1500. Nevertheless, we think it is valuable to make some observations of the period. Indeed, there considerable amount of evidence of harvest failures, although the reasons are rarely stated (Retsö, 2015). It is possible that prices of certain other goods contain climatological information, in particular wax and honey, which are both highly dependent on weather conditions in the summer. During the last 3 decades of the 16th century, production of bee wax was much reduced in Sweden, probably due to the transition to a cooler and wetter climate that was damaging to the bees (Husberg, 1994). Further archival research is needed to expand the wax price series needed for climatic research. Grain prices seem to be more associated with temperature than drought variability (Charpentier Ljungqvist, 2021).

Data on agricultural activities in the province of Östergötland are found for a few years in the first and last decades of the 15th century. Harvesting dates for 1402, 1407, and 1410 CE suggest close to normal summer temperature and precipitation (Lundén, 1958:141, 161, 133; Retsö, 2021), while available data of dates for sowing of barley and other grains and fodder for swine indicate a somewhat late or cold spring in 1491 CE and an early or warm spring in 1489, 1490 and 1492 CE (Alvered, 1999:104, 145, 192, 245).

Food crises are frequently mentioned in the 15th century, in particular in the 4 decades between 1430 CE and the early 1470s. It is assumed here that the mentioning of a food crisis in a particular year reflects a harvest failure the preceding year. As for the 1430s, we know that a period of crisis years began in 1435, and although we have no Swedish evidence of dearth for the first years of the decade, it can be noted that Danish and German sources mention hard times and high corn prices in 1433 CE that could be connected to cold springs (see Camenisch et al., 2016:2110). It is also conspicuous that a major peasant uprising occurred in Sweden in 1434 CE, and it can be inferred that this had something to do with a food crisis in combination with unusually high taxes. In the spring of 1437 CE, there was a lack of food grains in Finland, and famine and dearth in Sweden are mentioned in early 1438 CE (Hausen, 1921:no. 2220; Tunberg, 1937:214). The monetary valuations of the barley tithes in Funbo parish in Uppland in 1438 and 1439 CE more than doubled compared to the preceding years (Andræ, 1965). These years are well known in continental Europe as a time of food crises with concomitant social and economic impacts. The harvests of 1437 and 1438 CE were the worst in England during the 15th century, and the price of grain rose to an exceptionally high level in 1439 CE. The famines of the mid-1400s occurred in a context of repeated plague epidemics also hitting Sweden (Myrdal, 2003:249). They also fall within a subperiod of colder summers related to a Spörer minimum of solar activity within a longer period (1400–1550) of slightly warmer summers as compared to the 20th century, at least in northern Fennoscandia, according to tree-ring data; the eruption of Mount Fuji in 1435–1436 CE in Japan may have contributed to cold winters and late and cool summers in northwestern Europe during these years (Moberg et al., 2006:24, 26ff.; Campbell, 2009:30; Camenisch et al., 2016:2110).

The 1440s were also troubled by harvest failures. In 1442 CE the rye and hops harvest failed in Finland (Hausen, 1921:nos. 2512 and 2517; Bunge and Hildebrand, 1889:no. 955; see also Hausen, 1921:nos. 2521, 2528, 2529, 2535), and just a few years later the Vadstena abbey was forced to sell some of its valuable chalices and shrines in order to buy food due to the harvest failures in 1445 and 1446 CE (Riksarkivet (RA, the National Archive of Sweden), Stockholm, medieval codex A21 fol. 89r–v). From 1446 CE there is information on famine in Sweden (Hadorph, 1674:370ff.), and 1448 CE was described as a year of dearth in Stockholm due to a dry spring and a large amount of rain from late May onwards (Klemming, 1866:255).

The Vadstena annals describe the years 1454–1457 CE as struck by famine, which in the first of these years was combined with an outbreak of plague (Gejrot, 1996:286f., 292f.; Styffe, 1870:85; see also Christensen, 1895:297 no. 2; Fant, 1818:173, 175; Codex dipl. lub. 1:9, no. 328; von der Ropp, 1883:nos. 516, 520), and in 1470 CE there was famine in Finland (Hausen, 1924:no. 3142). This, as well as the harvest failure of 1460 CE, may have had something to do with a volcanic eruption in the Pacific in 1453 CE, marking the onset of a 15-year cool period (Esper et al., 2017).

The early 1470s also display evidence of a period of hot and dry weather, apparently an all-European phenomenon (Camenisch et al., 2020). In August 1474 CE the council of the Swedish realm issued a statute regulating the use of water mills due to repeated droughts, i.e., presumably causing lack of water (Hadorph, 1676:no. 9). Furthermore, a food crisis is indicated in a letter from Åbo (Turku), Finland, from May 1471 CE (Hausen, 1890:no. 625); in Sweden nominal grain prices display an unprecedented peak in the early 1470s (Franzén and Söderberg, 2006); and the Danish Roskilde annals speak of a “severely hot and burning summer” in Denmark in 1473 CE (Rørdam, 1873).

Summarizing, the years in the 15th century with harvest failures and/or unusually early onsets of the growing season are as follows:1402, 1405, 1436–1437, 1439, 1442, 1445–1446, 1448, 1453–1456, 1460, 1469–1470, 1473–1474, 1489, 1490, and 1492 CE.

From the first decade of the 16th century there are a number of reports of harvest failures and famine. In Västergötland, Småland, and the Stockholm area they speak of unsown fields, starving peasantry forced to eat bark, and expensive corn, which all points to a harvest failure in 1503 CE (RA Sturearkivet, nos. 255, 637; Styffe, 1875:no. 232). Shortage and poverty among the peasants are reported for the following year (Wegener, 1866–1870:319–320). In southwestern Finland, the harvest of 1507 CE had been consumed already in July 1508 and the peasantry suffered famine and “ate more bark than ever” (Hausen, 1930:nos. 5324, 5329). Similar reports are found for the same year from central Sweden and the Stockholm area (RA Sturearkivet, nos. 573, 597). The year 1508 CE seems to have been even worse. Again, prices of rye were high in March 1509 CE, and by harvest time in 1508 CE prices already were rising in Finland, and the misery was said to be the worst in 10 years; by the end of the year the country was ravaged by both great poverty and plague, rendering the peasantry unable to pay their taxes (Sjödin, 1937:336; Hausen, 1930:nos. 5341, 5347, 5354, 5368). The same was reported from Sweden: in March 1509 CE the peasants northeast of Stockholm starved and ate bark (Sjödin, 1937:322, 344; RA Sturearkivet, no. 1053; Styffe, 1875:no. 229). Widespread poverty was also reported as a result of a bad harvest in 1509 CE already in December of that year in central Sweden and in the spring and summer of 1510 CE (Sjödin, 1937:350; Styffe, 1875:nos. 302, 304; RA Sturearkivet, no. 1467).

In both Finland and southeastern Sweden there was severe drought in late spring and summer of 1551 CE (Almquist, 1905:115ff., 123ff., 212f., 430ff.). In the autumn there was also a severe drought in the Bergslagen mining area (Almquist, 1905:430ff.; Johansson, 1882:159f.). In June 1559 CE, the harvests of both rye and barley in Östergötland and southeastern Småland were already in danger in during blooming time due to both night frost and drought (Almquist, 1916:190, 202, 651). The same was reported from Finland in September (Almquist, 1916:287). Apart from 1551 and 1559 CE, there are also similar reports from other years of the 16th century, but they are sporadic, and it is uncertain as to how extensive the droughts were. In 1599 CE, there is evidence from southeastern Småland of severe heat and forest fires (Edman, 1985:74; see also Utterström, 1955:29; Hallendorff, 1902:79), and the production of honey was reduced drastically (Husberg, 1994:275).

For the 17th and 18th centuries sources are far more abundant and continuous, thanks to a number of private diaries among other sources. Some periods stand out as particularly hit by moderate to extreme drought. This is the case for 1634–1639, 1652–1657, 1665–1670, 1677–1684, 1746–1750, 1757–1767, 1771–1776, and 1780–1783 CE (with 2 years of extreme drought each) and 1634–1639 CE (with 1 year of extreme drought). Among these, 1652 and 1657 stand out as particularly troublesome. Other single years seem to have been dry on an all-European scale, e.g., 1540 CE (Wetter et al., 2014). Although some of the dry periods recorded in Sweden coincide with similar drought episodes in other areas of Europe (see, e.g., Brázdil et al., 2016), negative spatial correlations are to be expected between northern and southern Europe.

Eight periods stand out as particularly critical in terms of drought in the 17th and 18th centuries (for references for the particular years, see Table 4).

-

1634–1639 CE. There are reports of drought from the north and the south every year in this period. Weather conditions are characterized in the relatively detailed sources as being generally dry with a typical pattern of dry and cold springs, hot and warm summers, and rather wet autumns. The result was disaster for the harvest of hay but rather good harvests of rye. The hardships could even have begun earlier than 1634 CE; in June 1635 CE, Gabriel Gustafsson Oxenstierna wrote to his brother that poverty was widespread in the whole country after “the last years [i.e. plural] of dearth” (Sondén, 1890:363).

-

1652–1657 CE. The year 1652 CE was called the Great Drought Year already in contemporary sources. Several reports from virtually all regions of the country tell of dry weather caused by a lack of rain and excessive heat. According to one source, no rain fell between early May and late September, except for some thunderstorms in Karlstad and at Letstigen in the province of Närke in June. Grain and hay harvests suffered severely, except for rye, which fared slightly better, particularly in Finland. Great bushfires were rampant, destroying forests and rye in the fields. Water mills stood still due to dried-out rivers. The heat caused epidemics, killing many people, including members of the Royal Council. In addition, from 1657 there are reports covering all of Sweden about severe drought. Already in April the gardens were “longing for rain”. In Johan Rosenhane's diary from Östergötland, every day is noted to have been hot or very hot weather from early May to late August. Both the month of August and the entire year are said to have been so dry and hot that wells and streams went dry in Småland and Östergötland and that no one could remember such a drought. In the spring, 11 out of 65 iron mills in the Bergslagen region were unable to operate due to lack of water, especially those located by smaller rivers, and most of them had to limit their operations considerably during the whole year. The lack of water in the rivers running into Lake Mälaren is also shown by the fact that the water level of the lake was so low that sandbanks were visible. Even in the northern province of Norrbotten, the summer drought caused forest fires and a large amount of damage to the harvest.

-

1665–1670 CE. The last years of the 1660s were a new period of dry years. The year 1666 CE seems to have been the worst: already in July harvests were forecasted to fail, and at least in the west there was a lack of rain between late June and late September. In addition to this, in all of the following 4 years harvest failures are reported and water levels in lakes and streams were extremely low.

-

1677–1684 CE. The same pattern was repeated in the end of the 1670s and early 1680s. In particular, 1681 and 1684 CE stand out: in the former year Stockholm had no rain at all in April and May and hay harvests were weak, and in the latter there was a food crisis, with the peasants being required to pay their church tithes in cash rather than in grains.

-

1746–1750 CE. A new prolonged drought period occurred in the mid-1700s. Beginning in 1746 CE, there are repeated reports on spring drought, and in the following years also summer drought, from Hälsingland in the north to Västergötland in the west. Streams dried up, harvests failed, and bark beetles, favored by the hot weather, destroyed timber wood.

-

1757–1767 CE. Most of the growing seasons of this period were affected by dry weather with harvest failures and dried-up wells and marshes. Spring was particularly late in 1758 CE; in Stockholm harbor ice was said to be 1 m thick in late April, and there was still ice in inlets and small lakes in early May. The following summer was hot and dry, as were the summers of 1759, 1762, and 1764 CE. According to one source, the dry period extended from 1749 to 1767 CE at least in the north and with annually varying degrees of intensity.

-

1771–1776 CE. According to sources covering most of the southern half of the country, these years were all characterized by cold springs and hot and dry summers. Hay harvests failed due to dried-up wet meadows, and even rye failed to mature in due time. In particular 1775 CE stands out as a critical year. Barley, peas, and hay suffered severely, and lake water levels reached record lows. In the Stockholm region famine threatened in 1771 CE.

-

1780–1783 CE. From Västerbotten in the north to Blekinge in the south there are reports of cold springs and dry summers, dried-up wells and streams, and bushfires, and in Västergötland marshes were even so dry that they caught fire. In 1782 CE, sowing was delayed until the first week of May in the Stockholm region due to persisting ground frost. In Västerbotten in the north it only rained twice from summer to October in 1780 CE, and roots and cabbage failed, while the rye harvests were quite good, as was the hay harvest, probably due to cultivation on wet meadows watered by meltwater from the mountains. On the other hand, in all regions in the south the hay harvest seems to have failed, and the price of rye rose by more than a third over the year. The same pattern was repeated in 1781 and 1783 CE.

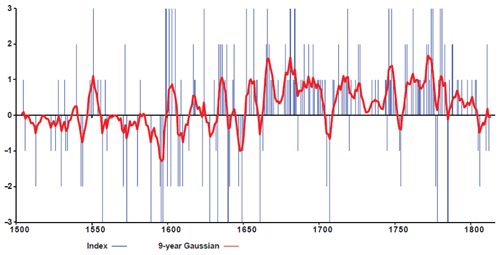

As can been seen in Fig. 1, there are many more instances that we have labeled as “dry”, especially in the 18th century, than there are instances of “wet” conditions. The word “rain” occurs 3361 times in the database (of a total of 20 896 entries), while the word “sun” only occurs 1224 times. However, varieties of “heat”, “dry”, and “warm” occur 1726 times compared to the two words describing “wet” in Swedish, which only occur 292 times. Many notices regarding rain are something similar to “a beautiful rain fell”, suggesting that rain was welcome. Generally, wet conditions are defining for agriculture in Scandinavia, but many fields are located such that they have a natural drainage (Leijonhufvud, 2001:130). These findings suggest that although instances of rain are more frequent than instances describing fine weather, consequences of “fine” weather were more troublesome. Figure 1 depicts the drought and precipitation index that has been constructed. Positive signs indicate descriptions of droughts that have caused problems or concern, and negative values indicate years when precipitation have been the cause for such impressions. Superimposed is a 9-year quasi-Gaussian smoothing filter.

Figure 1Drought and precipitation index for Sweden 1500–1816 CE. Note that we wish to thank Fredrik Charpentier Ljungqvist of Stockholm University for his help with the graphs.

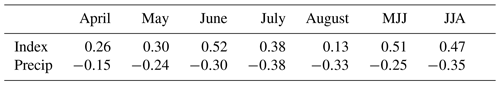

Correlation between proper instrumental data of temperature and precipitation from the same observational site of Observatorielunden in central Stockholm showed a slightly negative correlation between summer (June–July–August, JJA) temperatures and precipitation of −0.35. This result is similar to Moberg et al. (2003, Table VI), which is higher, probably because of the slightly different period used (1873–2000 CE).

Table 1Correlation between average monthly and seasonal temperatures in Stockholm and with the drought index of 1756–1816 CE (first row) and with the corresponding monthly and seasonal precipitation data from Stockholm for the period 1859–2011 CE (second row; daily observations are summed to monthly or seasonal values).

Precipitation data were downloaded from https://www.smhi.se/data/meteorologi/ladda-ner-meteorologiska-observationer/#param=precipitation24HourSum,stations= all,stationid = 98210 (last access: 22 January 2020).

Since there are no reliable instrumental precipitation data before 1860 CE, we have tested the index against the Stockholm temperature series from 1756 CE. Correlation between the index and average monthly temperature for the period 1756–1816 CE turned out to be significant for the months May, June, and July (Table 1), with the highest correlation received using May–June–July (MJJ) temperatures. However, since correlation for instrumental data between precipitation and temperature in May was very weak, we argue that the standard season of summer months (JJA) is more adequate in our exploration of droughts.

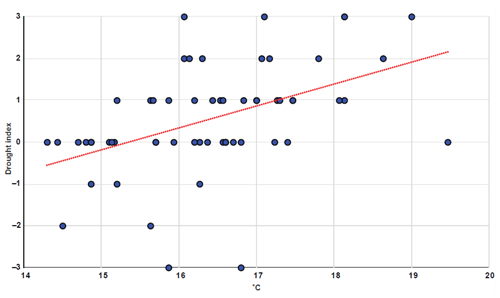

Figure 2 shows a scatterplot between summer temperatures in Stockholm and the drought index for Sweden.

Figure 2Scatterplot of JJA temperature for 1756–1816 CE and the drought index for Sweden. Note that “very dry” is +3, which should correspond to low levels of precipitation.

The index hardly has any correlation with August temperatures, while instrumental data renders a (slight) correlation between temperature and precipitation in August. We believe the main reason for this might be that the database may be more stringent when it comes to weather-related events occurring during the first half of the year. It is also possible that a cool May could be experienced as “wet”, and therefore it could be described as such in the sources forming the foundation of the index.

These tentative results of comparing the drought index made from descriptions of droughts and precipitation indicate that the descriptive sources are indeed correlated to climatic variables of temperatures and precipitation. In addition, although correlation is higher between temperature and index than between precipitation and index, the original data concern descriptions of dry or wet conditions, i.e., a description like “a hot/warm summer” is not included in the index.

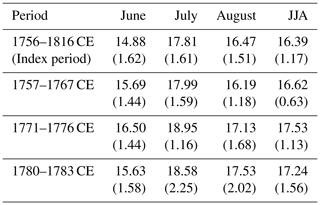

Since we have temperature measurements for the latter half of the 18th century, it is possible to quantify periods 6, 7, and 8 (1757–1767, 1771–1776, and 1780–1783 CE) in the section above. In Table 2, average monthly temperature for June, July, and August, as well as the entire summer season (JJA), are compared to average corresponding monthly or seasonal temperatures for the entire period 1756–1816 CE, i.e., until the year the index ends. None of the dry subperiods differ notably from average monthly temperature for any of the summer months or of the summer season. The period of 1771–1776 CE has the highest difference compared to average monthly temperature for the whole period 1756–1816 CE, being ca. 1 ∘C warmer.

Table 2Dry periods in the second half of the 18th century in Sweden reflected in instrumental measurements. Average monthly temperature for three subperiods.

From Fig. 2 it is visible that there are no indications of excessive precipitation when average JJA temperature is 17 ∘C or higher. Droughts, on the other hand, are prevalent from +15 ∘C, and very dry conditions may occur if temperatures are above 16 ∘C, confirming the average temperatures in Table 2.

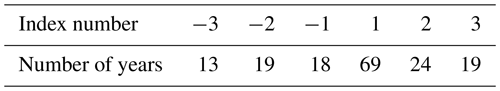

Since the index is a made of discrete variables, we thought it less meaningful to try out a regression analysis and model (which would only render seven different “temperatures”), especially since we have been concentrating on precipitation and not temperature. Finally, Table 3 summarizes the index presented in Fig. 1.

Table 3Droughts in Sweden 1500–1800 CE. The number of years that have been labeled anything but “normal” is shown.

Table 3 indicates that slightly dry (index value +1) years have been regarded as more “exceptional” than wetter (−1) years. When it comes to very wet (−2) or very dry (+2) and exceptionally wet (−3) or exceptionally dry (+3) years, there are a few more years denoted as dry than as wet. Out of 316 years, only 13 years were exceptionally wet and 19 exceptionally dry. An additional 19 years were very wet and 24 very dry. That comparably so few years were regarded as wet years (only 18), compared to 69 that were regarded as dry, may be a result of perception: nice summers were commonly commented upon in the sources.

In this paper we have tried to show that turning descriptions of drought (and precipitation) into an index does correlate with instrumental measures of temperature. We also provided descriptions of periods that suffered harvest failures through drought, precipitation, and adverse temperatures in the 15th century. Since the data are so scarce for the 13th to 15th centuries, we have not included that period into the index. Even results concerning at least the first half of the 16th century ought to be regarded as uncertain.

The main problem with the drought index is that we have a very short period (1786–1816) with overlapping data of precipitation and drought. In addition, instrumental data of precipitation might not be of very high quality. Therefore, lack of any correlation between the index and precipitation data may have three reasons. (1) The index rather reflects summer temperatures than drought and precipitation. (2) The instrumental precipitation data for the late 18th and early 19th century are not of very high quality. There is some correlation between the drought index and summer temperatures in Stockholm, just like there is some correlation between precipitation and summer temperatures. Correlation between the drought index and summer temperatures is higher than between summer temperatures and precipitation, and thus it is possible that the drought index is instead a temperature index. Hot summer temperatures will cause drought because in Sweden it very seldom rains when the weather is hot. (3) The drought index reflects data that come from different parts of Sweden. Instrumental precipitation data are, of course, from a very limited geographical area and will not reflect a general drought in Sweden.

Despite the shortcomings of the index, we still think that some conclusions may be drawn from it.

First, the height of the Little Ice Age (ca. 1570–1630 CE) is characterized by very high variations, with some years being extremely wet and some years being extremely dry.

Second, after the early 1660s, wet years became increasingly uncommon, and most years are either dry or very dry, especially from the mid-1700s onwards. Although previous estimates of Stockholm temperatures after 1756 CE have been shown to be positively biased, this seems to correspond to trends in tree-ring width and density at least in northern Fennoscandia (Moberg et al., 2003; Grudd, 2008).

For the late 13th to the early 16th century, a lack of data has made it impossible to extend the index so far back in time. Grain prices suggest difficulties in grain production around the turn of the 14th century. The highest price ever might reflect the catastrophic years of 1314–1316 – but the harvest failed that year because of wet and cold (Slavin, 2018:495–515) Therefore, we argue that grain prices alone cannot determine a specific climatic parameter (at least not for Sweden) since different conditions (too wet or too dry) result in the same outcome (dearth and higher prices).

-

Riksarkivet (National Archives of Sweden), Stockholm, Medieval codex A21.

-

Riksarkivet (National Archives of Sweden), Stockholm, Sturearkivet.

-

Riksarkivet (National Archives of Sweden), Stockholm, Brev från Catharina Wallenstedt, 1627–1719. Brev till dottern Margareta och sonen Carl. RA, Sjöholmsarkivet 1 enskilda samlingar, Ehrensteens samling, vol. 2.

-

Riksarkivet (National Archives of Sweden), Stockholm, Landshövdingars skrivelse t K M:t, Jönköpings län, Östergötlands län, Södermanlands län, Uppsala län, Stockholms län.

-

Riksarkivet (National Archives of Sweden), Stockholm, Kollegiers m fl skrivelser t K M:t. Generalguvernörers skrivelser, generalguvernören över Skåne, Halland samt Göteborgs och Bohus län.

-

Stockholms stadsarkiv (City archives of Stockholm), Magistratens ämbets- och byggnings Kollegium, Slussverket. Wattu journal 1774–1819.

The instrumental datasets are freely available and have been downloaded from the Bolin Centre (https://bolin.su.se/data/stockholm-historical-temps-monthly, Moberg, 2020; last access: 7 December 2019) and from SMHI (https://www.smhi.se/data/meteorologi/ladda-ner-meteorologiska-observationer/#param=precipitationMonthlySum,stations=all,stationid=98210, SMHI, 2020). E-mail contact with SMHI confirmed that the precipitation data from 1863 are missing.

LL wrote the methodological parts and the Results section, and DR the parts on sources and the descriptions of the documentary data, as well as Table 4 in the appendices. Sections 1 and 8 were written jointly.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Publisher's note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This article is part of the special issue “Droughts over centuries: what can documentary evidence tell us about drought variability, severity and human responses?”. It is not associated with a conference.

We wish to thank Fredrik Charpentier Ljungqvist at the Stockholm University for his help with the graphs.

The article processing charges for this open-access publication were covered by Stockholm University.

This paper was edited by Andrea Kiss and reviewed by two anonymous referees.

Ahlqvist, A.: Ölands historia och beskrifning, Del 2, Ahlquist, Upsala, Sweden, 1825.

Almquist, J. A. (Ed.): Konung Gustaf den förstes registratur, Del 23: 1552, Stockholm, Sweden, 1905.

Almquist, J. A. (Ed.): Konung Gustaf den förstes registratur, Del 29: 1559, 1560, Stockholm, Sweden, 1916.

Alvered, Z. (Ed.): Gregers Matssons kostbok för Stegeborg 1487–1492, Blom, Uppsala, Sweden, 1999.

Åmark, K.: Spannmålshandel och spannmålspolitik i Sverige 1710–1830, Stockholms högskola, Stockholm, Sweden, 1915.

Ambrosiani, S. (Ed.): Dokument rörande de äldre pappersbruken i Sverige, Gunnar Tisell, Stockholm, Sweden, 1923.

Andræ, C. G.: Studier kring Funbo kyrkas räkenskaper, Hist. tidskr.-Sweden, 85, 385–440, 1965.

Anteckningar ur Statistiska tabeller för Stockholms-Näs: http://www.ukforsk.se/svenparm/Sv2/Sv2-S-gard.pdf (last access: 12 September 2021), 1749–1859.

Barchaeus, A. G.: Underrättelser om landthushållningen i Halland, Gleerup. Lund, Sweden, 1924.

Bergh, S. (Ed.): Svenska riksrådets protokoll, Del 4: 1634, Stockholm, Sweden, 1886.

Bergh, S. (Ed.): Svenska riksrådets protokoll, Del 5: 1635, Stockholm, Sweden, 1888.

Bergstrand, C.-M.: Kulturbilder från 1700-talets Västergötland, Del 2, Göteborg, Sweden, 1934.

Bergstrand, C.-M.: Långareds krönika 1, Esborns bokhandel, Göteborg, Sweden, 1954.

Bergstrand, C.-M.: Essunga i svunnen tid, Essunga hembygds-och fornminnesförening, Göteborg, Sweden, 1955.

Brázdil, R., Dobrovolný, P., Trnka, M., Büntgen, U., Řezníčková, L., Kotyza, O., Valášek, H., and Štěpánek, P.: Documentary and instrumental-based drought indices for the Czech Lands back to AD 1501, Climate Res., 70, 103–117, 2016.

Broman, O.: Glysisvallur och öfriga skrifter rörande Helsingland, Del 1, Gestrike-Helsinge Nation i Upsala, Upsala, Sweden, 1911.

Brunnström, E. (Ed.): En dagbok från 1600-talet, författad av Andreas Bolinus, Norstedts, Stockholm, Sweden, 1913.

von Bunge, F. G. and Hildebrand, H. (Eds.): Liv- Esth- und Curlandisches Urkundenbuch nebst Regesten, Bd. 9, Reval, 1889.

Camenisch, C., Keller, K. M., Salvisberg, M., Amann, B., Bauch, M., Blumer, S., Brázdil, R., Brönnimann, S., Büntgen, U., Campbell, B. M. S., Fernández-Donado, L., Fleitmann, D., Glaser, R., González-Rouco, F., Grosjean, M., Hoffmann, R. C., Huhtamaa, H., Joos, F., Kiss, A., Kotyza, O., Lehner, F., Luterbacher, J., Maughan, N., Neukom, R., Novy, T., Pribyl, K., Raible, C. C., Riemann, D., Schuh, M., Slavin, P., Werner, J. P., and Wetter, O.: The 1430s: a cold period of extraordinary internal climate variability during the early Spörer Minimum with social and economic impacts in north-western and central Europe, Clim. Past, 12, 2107–2126, https://doi.org/10.5194/cp-12-2107-2016, 2016.

Camenisch, C., Brázdil, R., Kiss, A., Pfister, C., Wetter, O., Rohr, C., Contino, A., and Retsö, D.: Extreme heat and drought in 1473 and their impacts in Europe in the context of the early 1470s, Reg. Environm. Change, 20, 1–15, 2020.

Campbell, B. M. S.: Four famines and a pestilence: Harvest, price, and wage variations in England, 13th to 19th centuries, in: Agrarhistoria på många sätt: 28 studier om människan och jorden, edited by: Liljewall, B., Flygare, I. A., Lange, U., Ljunggren, L., and Söderberg, J., Kungl. Skogs-och lantbruksakademien, Stockholm, Sweden, 2009.

Charpentier Ljungqvist, F., Thejll, P., Christiansen, B., Seim, A., Hartl, C., and Esper, J.: The significance of climate variability on early modern European grain prices, Cliometrica, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11698-021-00224-7, online first, 2021.

Christensen, W.: Unionskongerne og Hansestæderne 1439–1466, Gad, København, Denmark, 1895.

Codex diplomaticus lubecensis, Abt. 1, Urkundenbuch der Stadt Lübeck, T. 9, Verein für Lübeckische Geschichte und Alterthumskunde, Lübeck, Germany, 1893.

Danielson, T.: Stöpsjöhyttan 1601–1974, Bronells, Filipstad, Sweden, 1974.

Edén, N. (Ed.): Rikskansleren Axel Oxenstiernas skrifter och brefvexling Afd. 2. Bd. 11, Carl Bonde och Louis De Geer m. fl. bref angående bergverk, handel och finanser, Kungl. Vitterhets historie och antikvitets akademien, Stockholm, Sweden, 1905.

Edman, B.: ...”aro fem valar vid Ronnö: ur Ålems äldsta kyrkbok, Kalmar län, Sweden, 70, 1985.

Ejdestam, J.: De fattigas Sverige, Rabén & Sjögren, Stockholm, Sweden, 1969.

Elvius, P.: Dagbok, 1748.

Esper, J., Büntgen, U., Hartl-Meier, C., Oppenheimer, C., and Schneider, L.: Northern Hemisphere temperature anomalies during the 1450s period of ambiguous volcanic forcing, B. Volcanol., 79, 41, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00445-017-1125-9, 2017.

Falkengren, C.: Några anmärkningar angående årstiderna och väderleken, ifrån år 1617 till år 1639, fundne uti Kongl. Riks-Archivum, Kungl. Svenska vetenskapsakademiens handlingar, Stockholm, 1781.

Fant, E. M. (Ed.): Scriptores rerum svecicarum medii ævi, Tomus 1: Scriptores rerum svecicarum medii ævi ex schedis præcipue nordinianis collectos dispositos ac emendatos, Upsaliæ, Sweden, 1818.

Forssell, H.: Anteckningar om Sveriges jordbruksnäring i sextonde seklet, Stockholm, Sweden, 1884.

Franzén, B and Söderberg J.: Svenska spannmålspriser under medeltiden i ett europeiskt perspektiv, Hist. tidskr.-Sweden, 126, 189–214, 2006.

Fredriksson, K.: Sandhems gårdskrönikor med särskild hänsyn till 1600-talet, Del 2: Gårdar med namn börjande på L-Ö, Sandhems hembygds- och fornminnesförening, Sandhem, Sweden, 1979.

Fritz, S.: Jennings och Finlay på marknaden för öregrundsjärn och besläktade studier i frihetstida storföretagande och storfinans, Kungl. Vitterhets historie och antikvitets akademien, Stockholm, Sweden, 2010.

Fryxell, A.: Handlingar rörande Sverges historia 1, Stockholm, Sweden, 1836.

Gejrot, C. (Ed.): Vadstenadiariet: Latinsk text med översättning och kommentar, Samf. för utgivande av handskrifter rörande Skandinaviens historia, Stockholm, Sweden, 1996.

Göthe, G.: Om Umeå lappmarks svenska kolonisation från mitten av 1500-talet till omkr. 1750, Almqvist & Wiksell, Uppsala, Sweden, 1929.

Grudd, H.: Torneträsk tree-ring width and density AD 500–2004: A test of climatic sensitivity and a new 1500 year reconstruction of north Fennoscandian summers, Clim. Dynam., 31, 843–857, 2008.

Hadorph, J.: Dahle laghen, then i forna tijder hafwer brukat warit öfwer alla Dalarna och them som in om Dala råmärken bodde, Johan Georg Eberdt, Stockholm, Sweden, 1676.

Hadorph, J.: Två gambla swenske rijm-krönikor..., Nicol. Wankijff, Stockholm, Sweden, 1674.

Hallendorff, C.: Ur en svensk kyrkobok från slutet av 1500-talet, Meddelanden och aktstycken, Kyrkohistorisk årsskrift, 1902.

Hannerberg, D.: Närkes landsbygd 1600–1820: Folkmängd och befolkningsrörelse, åkerbruk och spannmålsproduktion, Högskolan i Göteborg, Göteborg, Sweden, 1941.

Hausen, R. (Ed.): Diarium Gyllenianum eller Petrus Magni Gyllenii dagbok 1622–1677, Helsingfors, Finland, 1880.

Hausen, R. (Ed.): Registrum ecclesiæ Aboensis eller Åbo domkyrkas svartbok, med tillägg ur Skoklosters codex Aboensis, Finlands statsarkiv, Helsingfors, Finland, 1890.

Hausen, R. (Ed.): Finlands medeltidsurkunder, Vols. 3, 4, 6, Finlands statsarkiv, Helsingfors, Finland, 1921, 1924, 1930.

Hegardt, A.: Akademiens spannmål: Uppbörd, handel och priser vid Uppsala universitet 1635–1719, Almqvist & Wiksell, Uppsala, Sweden, 1975.

Hellgren, M. (Ed.): En kyrkoherdes vardag: Anteckningar 1700–1758, Ekshärad, Forshaga, Sweden, 1996.

Hiorter, O.: Utdrag af framledne observatoren Hiorters meteorologiska observationer, hållne i Upsala år 1748, inlemnadt af Bengt Ferner, K. Svenska vetenskapsakademiens handlingar, Vol. 13, 1752.

Hiorter O. K.: Sv. Vetenskapsakademiens handlingar, Utdrag af meteorologiska observationer, håldne Upsala åhr 1746, 1747.

Hisdal, H. and Tallaksen, L. M. (Eds.): Drought event definition, Technical report to the ARIDE Project no 6, Oslo, Dept of Geophysics, University of Oslo, Oslo, Norway, 2000.

Hofrén, M.: Tryserum: Några kapitel ur Tryserums och Fogelviks historia, [Tryserum], [Tryserums hembygdsfören.], 1984.

Hülphers Abramsson, A.: Utdrag af Kyrkoherden i Ryttern Nic. Nic. Kroks anmärkningar i Almanackor, Kongl. Vetenskaps academiens nya handlingar tom XIV för år 1793, Stockholm, Sweden, 1793.

Husberg, E.: Honung, vax och mjöd: Biodlingen i Sverige under medeltid och 1500-tal, Göteborgs universitet, Göteborg, Sweden, 1994.

Hushållnings Journal, Stockholm, October 1786.

Ilmoni, I.: Bidrag till nordens sjukdoms-historia Del 3: Bidrag till historien om Nordens sjukdomar från början af det adertonde seklets andra decennium till samma århundrades slut, J. Simelii arfvingar, Helsingfors, 1853.

Isacson, C.-G.: Karl X Gustavs krig: Fälttågen i Polen, Tyskland, Baltikum, Danmark och Sverige 1655–1660, Historiska media, Lund, Sweden, 2004.

Jansson, A. (Ed.): Johan Rosenhanes dagbok, Samfundet för utgivande av handskrifter rörande Skandinaviens historia, Stockholm, Sweden, 1995.

Jansson, E. A.: Ortala bruk, Med hammare och fackla, 16, 1947.

Johansson, J. (Ed.): Om Noraskog: Äldre och nyare anteckningar, Del 1, Stockholm, Sweden, 1882.

Klemming, G. E. (Ed.): Svenska medeltidens rimkrönikor, Del 2, Nya eller Karls-krönikan: Början av unionsstriderna samt Karl Knutssons regering, 1389–1452, Stockholm, Sweden, Norstedt, 1866.

Landshövdingen öfver Skaraborgs län Tord Bonde Ulfssons berättelser för åren 1661–1666, Berättelse för åren 1665 och 1666. Handlingar rörande Skandinaviens historia, 31, Stockholm, Sweden, 1850.

Leijonhufvud, L.: Grain Tithes and Manorial Yields in Early Modern Sweden: Trends and Patterns of Production and Productivity c. 1540–1680, Sveriges lantbruksuniversitet, Uppsala, Sweden, 2001.

Levander, L.: Fattigt folk och tiggare, Åhlen & söner, Stockholm, Sweden, 1934.

Lindgren, H.: Spannmålshandel och priser vid Uppsala akademi 1720–1789: En prövning av markegångstaxornas källvärde, Uppsala universitet, Uppsala, Sweden, 1971.

Lindroth, S.: Gruvbrytning och kopparhantering vid Stora Kopparberget intill 1800-talets början, Del 2: Kopparhanteringen, Almqvist & Wiksell, Uppsala, Sweden, 1955.

Löf, A. E.: Kristinehamns historia, Del 1, Karlstad, Sweden, 1942.

Lundén, T. (Ed.): Den helige Nikolaus' av Linköping liv och underverk, Credo, 39, 97–173, 1958.

Malmberg, E.: Strömsbergs bruks historia, Almqvist & Wiksell, Uppsala, Sweden, 1917.

Moberg, A.: Stockholm Historical Weather Observations – Monthly mean air temperatures since 1756, Dataset version 2.0, Bolin Centre Database [data set], https://doi.org/10.17043/stockholm-historical-temps-monthly-2, 2020.

Moberg, A., Alexandersson, H., Bergström, H., and Jones, P. D.: Were southern Swedeish summer temperatures before 1860 as warm as measured?, Int. J. Climatol., 23, 1495–1521, https://doi.org/10.1002/joc.945, 2003.

Moberg, A., Gouirand, I., Kjellström, E., de Jong, R., Linderholm, H., and Zorita, E.: Climate in Sweden during the past millennium: Evidence from proxy data, instrumental data and model simulations, Technical Report TR-06-35, Svensk Kärnbränslehantering, Stockholm, 2006.

Myrdal, J.: Digerdöden, pestvågor och ödeläggelse: Ett perspektiv på senmedeltidens Sverige, Sällsk. Runica et mediævalia, Stockholm, 2003.

Norberg, P.: Gästriklands hyttor och hamrar, Blad för bergshanteringens vänner, Almqvist & Wiksell, Stockholm, 33, 1958–1959.

Nordenström, M. N.: Utkast till beskrifning öfwer Stöde socken vid Medelpads södra ådal belägen, C. E. Fritze, Stockholm, Sweden, 1894.

Nordlander, J.: Johan Graan: Landshövding i Västerbotten 1653–1679, Thule, Stockholm, Sweden, 1938.

Ny journal uti hushållningen 1776–1813, del 1, 3, Upplands-Bro, Upplands-Bro kulturhistoriska forskningsinstitut, Sweden, 2001.

Olander, G.: Spannmålspriser i Västergötland 1725–1774, Västergötlands fornminnesförenings tidskrift, 6, 109–126, 1951.

Olofsson, S. I., and Liedgren, J.: Övre Norrlands historia, Del 3: Tiden 1638–1772, Norrbottens och Västerbottens läns landsting, Umeå, Sweden, 1974.

Omberg, T.: Bergsmän i hyttelag: Bergsmannanäringens utveckling i Linde och Ramsberg under en 100-årsperiod från mitten av 1700-talet, Jernkontoret, Uppsala, Sweden, 1992.

Osbeck, P.: Utkast till beskrifning öfver Laholms prosteri 1796, Gleerup, Lund, Sweden, 1922.

Osvald, H.: Potatisen, Natur och kultur, 1965.

Palm Andersson, L.: Gud bevare utsädet! Produktionen på en västsvensk ensädesgård: Djäknebol i Hallands skogsbygd 1760–1865, Kungl. Skogs- och lantbruksakademin, Stockholm, Sweden, 1997.

Pehrsson, P.: Anmärkningar öfwer Broddetorps pastorat, jämte wäderleken, årswäxten och sädespriserna därstädes ifrån och med 1746 til och med 1774, Hushållnings Journal, 1781.

Petersson, E.: Allmogens i Blekinge besvär inför skånska kommissionen 1669–1670, Del 3: Bräkne härad, Karlskrona, Sweden, 1942.

Rääf, L. F.: Samlingar och anteckningar till en beskrifning öfver Ydre härad, Del 1, Linköping, Sweden, 1856.

Retsö, D.: Documentary evidence of historical floods and extreme rainfall events in Sweden 1400–1800, Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci., 19, 1307–1323, https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-19-1307-2015, 2015.

Retsö, D.: Normality and anomaly in `Little Ice Age Sweden': Interpreting weather events in late medieval and early modern documentary sources, in preparation, 2021.

Rørdam, H. (Ed.): Historiske kildeskrifter og bearbejdelser af dansk historie især fra det 16. aarhundrede, R. 1, Bd. 1, Gad, Kjøbenhavn, Denmark, 1873.

Schiller, H. (Ed.): Med göter genom göternas rike: Sockenbeskrivningar, Malmö, 1933.

Schissler, P.: Jerlsö sokns i Helsingeland beskrifning, 1753, Rediviva, nytryck Stockholm, Sweden, 1972.

Sidenbladh, E.: Sällsamma händelser i Sverige med Finland åren 1749–1801 och i Sverige åren 1821–1859, Stockholm, Sweden, 1908.

Sillén, A. W. af: Svenska handelns och näringarnes historia, Uppsala, Sweden, 1855.

Sjöberg, N. (Ed.): Johan Ekeblads bref, Del 2: Från Karl X:s fälttåg samt lifvet i hufvudstaden, Norstedt, Stockholm, Sweden, 1915.

Sjöberg, S.: Ankarsmide under vattenhammare, Söderfors 300 år, Stora Kopparbergs bergslags AB, Falun, 1976.

Sjödin, L. (Ed.): Arvid Siggessons brevväxling, Mora, Sweden, 1937.

Slavin, P.: The 1310s Event, The Palgrave Handbook of Climate History, edited by: White, S., Pfister, C., and Mauelshagen, F., London, UK, Palgrave Macmillan, 2018.

Söderberg, J.: Åkerbruk och boskapsskötsel, Mora: ur Mora, Sollerö, Venjans och Våmhus socknars historia, Del 3, edited by: Täpp J.-E. Pettersson, and Karlsson, O., Mora kommun, Mora, Sweden, 1999.

Söderberg, J. and Myrdal, J.: The Agrarian Economy of Sixteenth-Century Sweden, Stockholms universitet, Stockholm, Sweden, 2002.

Sondén, P. (Ed.): Rikskansleren Axel Oxenstiernas skrifter och brefvexling Afd. 2. Bd. 3: Gabriel Gustafsson Oxenstiernas bref 1611–1640. 2: Per Brahes bref 1633–1651, Kungl. Vitterhets historie och antikvitets akademien, Stockholm, Sweden, 1890.

Steckzén, B.: Umeå stads historia 1588–1888, Två förläggare, Umeå, Sweden, 1981.

Styffe, C. G. (Ed.): Bidrag till Skandinaviens historia ur utländska arkiver, Del 3, 4, Norstedt, Stockholm, Sweden, 1870, 1875.

Sveriges meteorologiska och hydrologiska institut (SMHI): https://www.smhi.se/data/meteorologi/ladda-ner-meteorologiska-observationer/#param=precipitationMonthlySum,stations=all,stationid=98210, last access: 5 February 2020.

Tessin, C. G.: Tessin och tessiniana, Stockholm, Sweden, 1819.

Thunaeus, H.: Ölets historia i Sverige, Del 1: Från äldsta tider till 1600-talets slut, Almqvist & Wiksell, Stockholm, Sweden, 1968.

Tilander, G. (Ed.): Reflexer från stormaktstiden: Ur Andreas Julinus brevväxling, CETE, Borås, Sweden, 1976.

Trolle-Bonde, C.: Hesselby: Arkivalier rörande egendomen och dess egare samt Bonde-grafven i Spånga kyrka, Lund, Sweden, 1894.

Tunberg, S. (Ed.): Svenska medeltidsregester: Förteckning över urkunder till Sveriges historia 1434–1441, Norstedt, Stockholm, Sweden, 1937.

Utterström, G.: Climatic Fluctuations and Population Problems in Early Modern History, Scandinavian Economic History Review, 3–47, 1955.

Utterström, G.: Jordbrukets arbetare: Levnadsvillkor och arbetsliv på landsbygden från frihetstiden till mitten av 1800-talet, Del 2, Tiden, Stockholm, Sweden, 1957.

von der Ropp, G. (Ed.): Hanserecesse, Abt. 2, Von 1431–1476, Bd. 4, Duncker & Humblot, Leipzig, Germany, 1883.

Wallén, A.: Vänerns vattenståndsvariationer, Hydrografiska byrån, Stockholm, Sweden, 1910.

Wallerius, J. G.: Observationer vid Åker-bruket, gjorda i 30 år, K. Vetenskapsakademiens handlingar jan-mars, Kungl. Vetenskapsakademin, Stockholm, 1779.

Wegener, C. F. (Ed.): “Forhandlinger mellem Danmark og Sverig i Kong Hans's Tid”, Aarsberetninger fra det Kongelige Geheimearchiv, indeholdende Bidrag til dansk Historie fra utrykte Kilde, Kongelige Geheimearchiv, Kjöbenhavn, Denmark, 1866–1870.

Weibull, C. G.: Skånska jordbrukets historia intill 1800-talets början, Gleerup, Lund, Sweden, 1923.

Weinhagen, A.: Norbergs bergslag samt Gunnilbo och Ramnäs till omkring 1820: Studier i områdets närings- och bebyggelsegeografi, Gleerup, Lund, Sweden, 1947.

Westerlund, J. A. and Setterdahl, J. A.: Linköpings stifts herdaminne, Del 3:1, Linköping, Sweden, 1917.

Wetter, O., Pfister, C., Werner, J. P., Zorita, E., Wagner, S., Seneviratne, S. I., Herget, J., Grünewald, U., Luterbacher, J., Alcoforado, M.-J., Barriendos, M., Bieber, U., Brázdil, R., Burmeister, K. H., Camenisch, C., Contino, A., Dobrovolný, P., Glaser, R., Himmelsbach, I., Kiss, A., Koryza, O., Labbé, T., Limanówka, D., Litzenburger, L., Nordli, Ø., Pribyl, K., Retsö, D., Riemann, D., Rohro, C., Siegfried, W., Söderberg, J., and Spring, J.-L.: The year-long unprecedented European heat and drought of 1540 – a worst case, Climatic Change, 125, 349–363, 2014.

Widegren, P. D.: Försök till en ny beskrifning öfwer Östergötland, Linköping, Sweden, 1828.

Wijkmark, Ch. (Ed.): Allrakäraste: Catharina Wallenstedts brev 1672–1718, Atlantis, Stockholm, Sweden, 1995.

Wittrock, G.: Regering och allmoge under Kristinas förmyndare, K. Humanistiska vetenskapssamfundet i Uppsala, Uppsala, Sweden, 1948.

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Sources

- Instrumental measurements

- Method for the reconstruction of a drought and precipitation index series

- Documentary data of droughts for the 15th and 16th centuries: some observations

- Documentary data of droughts for the 17th and 18th centuries

- Results

- Discussion and conclusions

- Appendix A: Archival sources

- Data availability

- Author contributions

- Competing interests

- Disclaimer

- Special issue statement

- Acknowledgements

- Financial support

- Review statement

- References

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Sources

- Instrumental measurements

- Method for the reconstruction of a drought and precipitation index series

- Documentary data of droughts for the 15th and 16th centuries: some observations

- Documentary data of droughts for the 17th and 18th centuries

- Results

- Discussion and conclusions

- Appendix A: Archival sources

- Data availability

- Author contributions

- Competing interests

- Disclaimer

- Special issue statement

- Acknowledgements

- Financial support

- Review statement

- References