the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Winter–spring warming in the North Atlantic during the last 2000 years: evidence from southwest Iceland

James M. Russell

Johanna Garfinkel

Yongsong Huang

Temperature reconstructions from the Northern Hemisphere (NH) generally indicate cooling over the Holocene, which is often attributed to decreasing summer insolation. However, climate model simulations predict that rising atmospheric CO2 concentrations and the collapse of the Laurentide Ice Sheet caused mean annual warming during this epoch. This contrast could reflect a seasonal bias in temperature proxies, and particularly a lack of proxies that record cold (late fall–early spring) season temperatures, or inaccuracies in climate model predictions of NH temperature. We reconstructed winter–spring temperatures during the Common Era (i.e., the last 2000 years) using alkenones, lipids produced by Isochrysidales haptophyte algae that bloom during spring ice-out, preserved in sediments from Vestra Gíslholtsvatn (VGHV), southwest Iceland. Our record indicates that winter–spring temperatures warmed during the last 2000 years, in contrast to most NH averages. Sensitivity tests with a lake energy balance model suggest that warmer winter and spring air temperatures result in earlier ice-out dates and warmer spring lake water temperatures and therefore warming in our proxy record. Regional air temperatures are strongly influenced by sea surface temperatures during the winter and spring season. Sea surface temperatures (SSTs) respond to both changes in ocean circulation and gradual changes in insolation. We also found distinct seasonal differences in centennial-scale, cold-season temperature variations in VGHV compared to existing records of summer and annual temperatures from Iceland. Multi-decadal to centennial-scale changes in winter–spring temperatures were strongly modulated by internal climate variability and changes in regional ocean circulation, which can result in winter and spring warming in Iceland even after a major negative radiative perturbation.

- Article

(3062 KB) - Full-text XML

- BibTeX

- EndNote

Temperatures in the Northern Hemisphere (NH) are generally thought to have cooled over the past 2000 years, culminating in the Little Ice Age (LIA, ca. 1450–1850 CE) (Kaufman et al., 2009; PAGES 2K Consortium, 2013, 2019; McKay and Kaufman, 2014). However, the majority of NH temperature reconstructions are based on proxies that respond to climate change during the warm season and may not capture trends in annual or winter and spring temperatures (Liu et al., 2014; PAGES 2K Consortium, 2019). This limits our understanding of major atmospheric phenomena in the NH, such as the North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO), which dominates wintertime variability, as well as changes in ocean circulation and other phenomena driving variability in the extent of Arctic sea ice.

Many oceanic and atmospheric processes that influence surface climate in the Atlantic and the broader NH are centered in the high North Atlantic region, making it an important location to study changes during the winter and spring seasons (Hurrell, 1995; Yeager and Robson, 2017). Terrestrial paleoclimate records from Iceland, for instance, have the potential to resolve temperature changes during the winter and spring seasons as this region is sensitive to the NAO and sits near the southern limit of Arctic sea ice (Hurrell, 1995; Hanna et al., 2004, 2006). The high sedimentation rates in Icelandic lakes, along with well-known volcanic eruptions that can be used as age constraints on sediment successions, make this an ideal location and archive to test how winter and spring temperatures evolved over the past 2000 years (Larsen and Eiríksson, 2008; Geirsdóttir et al., 2009, 2019; Larsen et al., 2011; Langdon et al., 2011; Holmes et al., 2016). However, existing terrestrial records of temperature from Iceland are limited due to their sensitivity to the warm season, low temporal resolution and length, or compounding effects on proxies from human land use or precipitation over the past 2000 years.

Here we present a reconstruction of winter–spring temperatures developed using well-dated lake sediments from southwest Iceland to assess seasonal temperature changes in the North Atlantic climate over the past 2000 years. We take advantage of alkenone production by Group I Isochrysidales (i.e., haptophyte algae) during the spring season to develop a record of winter–spring temperatures and investigate the forcings responsible for cold-season temperature changes using a lake energy balance model.

2.1 Study site and age model

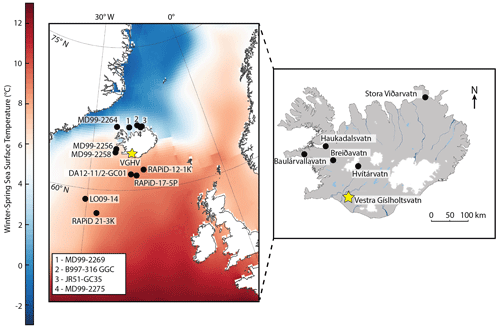

Vestra Gíslholtsvatn (VGHV) is a small lake (1.57 km2) located in southwest Iceland (61 m a.s.l.; 63∘56′ N, 20∘31′ W; Fig. 1), about 25 km from the coast (Blair et al., 2015). Mean monthly temperatures range from −1.4 ∘C during the winter months (DJF) to 10.4 ∘C during the summer months (JJA) (station at Hella, 1958–2005 CE; Icelandic Meteorological Office, 2012). Cores were collected in 2008 using a Bolivia piston coring system (Blair et al., 2015), and were sampled at the National Lacustrine Core Facility (LacCore) at the University of Minnesota.

Figure 1Map of mean winter–spring (DJFMAM) sea surface temperatures from 1955–2017 in the high North Atlantic region. The marine sediment cores MD99-2269 (Moros et al., 2006; Justwan et al., 2008; Cabedo-Sanz et al., 2016), B997-316 GGC (Harning et al., 2019), JR51-GC35 (Cabedo-Sanz et al., 2016), MD99-2275 (Jiang et al., 2005, 2015; Massé et al., 2008; Sicre et al., 2008; Ran et al., 2011), MD99-2264 (Ólafsdóttir et al., 2010), MD99-2256 (Ólafsdóttir et al., 2010), MD99-2258 (Axford et al., 2011), DA12-11/2-GC01 (Orme et al., 2018; Van Nieuwenhove et al., 2018), RAPiD-12-1K (Thornalley et al., 2009), RAPiD-17-5P (Moffa-Sánchez et al., 2014), LO09-14 (Berner et al., 2008), and RAPiD 21-3K (Sicre et al., 2011; Miettinen et al., 2012) that are discussed in the text are indicated. The locations of lake sediment records from Stora Viðarvatn (Axford et al., 2009), Haukadalsvatn (Geirsdóttir et al., 2009), Baulárvallavatn (Holmes et al., 2016), Breiðavatn (Gathorne-Hardy et al., 2009), and Hvítárvatn (Larsen et al., 2011) are indicated. The study site, Vestra Gíslholtsvatn (VGHV), is marked by a yellow star. The maps were made using data from Natural Earth, the National Land Survey of Iceland, and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) World Ocean Database (Boyer et al., 2018).

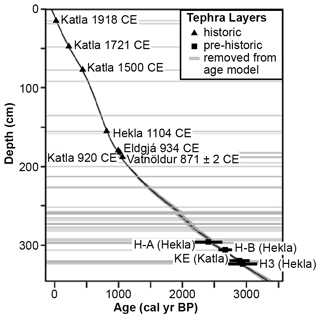

The VGHV cores were dated using previously identified tephra, including seven historical and four pre-historical tephra beds (Blair et al., 2015, and references therein). The age model was developed using “classical” age modeling (CLAM) with a smoothed spline fit (Blaauw, 2010). The resulting age model has an uncertainty of 5 to 15 years from −50 to 1200 yr BP and 18 to 83 years from 1201 to 2000 yr BP (Fig. 2).

2.2 Lipid analyses

Sediments were freeze-dried and extracted using a Dionex™ accelerated solvent extraction (ASE 350) system at 120 ∘C and 1200 psi. All of the extracts were separated by silica gel (40–63 µm, 60 Å) flash chromatography to obtain alkane (hexane; Hex), ketone (dichloromethane; DCM), and polar (methanol; MeOH) fractions. Saponification was used to remove wax esters by dissolving the dried ketone fraction in a 1 molar potassium hydroxide solution with MeOH : H2O (95:5, ) and heating the samples for 3 h at 65 ∘C. Solutions consisting of 5 % NaCl in H2O and 50 % HCl in H2O were added to the samples and the lipid faction was extracted using Hex (100 %). Ketone fractions were further purified using silver nitrate columns (D'Andrea et al., 2007) with DCM (100 %) followed by ethyl acetate (100 %) to elute the alkenones. If additional cleaning was needed, a modified procedure from Salacup et al. (2019) was used. The alkenone fraction was dried under N2 gas and re-dissolved in 1.5 mL of DCM : Hex (2:1, ). To this, a 1.5 mL solution of 100 mg mL−1 urea in MeOH was added. The resulting crystals were dried under N2 gas, and the urea addition was repeated two more times. The dried urea crystals were cleaned with Hex (100 %) and extracted as the non-adduct. Milli-Q water was added to the vial to fully dissolve the urea crystals, and the adduct was extracted using Hex (100 %). The samples were then analyzed for alkenones. For several samples, co-eluting compounds were still present, or concentrations were too low for reliable quantification. These samples were not included in our final reconstruction.

The resulting alkenone fraction was analyzed using an Agilent 6890N gas chromatography (GC) and flame ionization detector (FID) system with an Agilent VF-200ms capillary column (60 m × 250 µm × 0.10 µm). Samples were injected into a cooled injection system–programmed temperature vaporizer (CIS-PTV) inlet in solvent vent mode (6.9 psi at 112 ∘C). The oven program was set to 50 ∘C and increased to 235 ∘C at 20 ∘C min−1 and ramped to 320 ∘C at 1.39 ∘C min−1, where it was held isothermally for 5 min. An alkenone standard was injected twice every 8 to 10 samples to assess the analytical precision of the alkenone measurements. The standard deviation for the calculated index (see Eq. 1) was 0.0040 (n=28). For additional verification or identification of co-eluting compounds, samples were run on an Agilent 6890N GC system coupled with an Agilent 5793N quadrupole mass spectrometer (MS). All samples were injected with pulsed splitless injection mode (20 psi at 315 ∘C) and run on an Agilent VF-200ms capillary column (60 m × 250 µm × 0.10 µm). The oven program was started at 40 ∘C for 1 min, ramped up to 255 ∘C at 20 ∘C min−1, increased again to 315 ∘C at 2 ∘C min−1, and then held isothermally for 10 min. The MS ionization energy was set to 70 eV with a scan range of 50 to 600 .

2.3 Alkenones as a proxy for lake water temperatures

Alkenones are long-chain ketones produced by Isochrysidales haptophyte algae in both marine and lacustrine environments. Numerous marine-based culture and core-top studies show that variations in alkenone saturation (i.e., changes in C37:3Me and C37:2Me production) are inversely correlated with temperature and can be linearly calibrated to temperature using either the or index (Brassell et al., 1986; Prahl and Wakeham, 1987; Prahl et al., 1988; Müller et al., 1998; Conte et al., 2006). Similarly, culture studies, core tops, and in situ measurements in lakes show that changes in alkenone saturation are also correlated with temperature (Zink et al., 2001; Sun et al., 2007; Toney et al., 2010; D'Andrea et al., 2011, 2012, 2016; Wang and Liu, 2013; Nakamura et al., 2014; Longo et al., 2016, 2018; Zheng et al., 2016). The index can be applied to lacustrine environments and is calculated as follows:

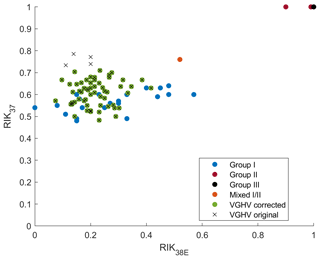

Sedimentary alkenones may derive from multiple alkenone-producing species, mainly groups I and II Isochrysidales, with distinct alkenone signatures and varying responses to temperature (Coolen et al., 2004; Sun et al., 2007; Theroux et al., 2010, 2013; Ono et al., 2012; Toney et al., 2012; Nakamura et al., 2014; D'Andrea et al., 2016). Group I Isochrysidales produces distinct tri-unsaturated alkenones (e.g., CMe and CEt), which can be used to test for species-mixing effects with the following ratios for isomeric ketones (RIK37 and RIK38E) (Longo et al., 2016):

An RIK37 value of 1.0 suggests a predominance of the C37:3Me and the presence of Group II Isochrysidales, while values from 0.48 to 0.63 are empirically shown to correspond to Group I Isochrysidales (Longo et al., 2016, 2018). RIK38E values of 0 to 0.57 were empirically shown to correspond to Group I alkenone distributions, whereas Group II alkenone distributions correspond to values between 0.75 to 1 (Longo et al., 2016, 2018).

Group I Isochrysidales and their corresponding alkenones have, so far, only been identified in Northern Hemisphere lakes at latitudes ranging from 42–81∘ N (Longo et al., 2018; Richter et al., 2019). The Northern Hemisphere lake calibration for Group I alkenones, which includes VGHV, was developed using the average spring temperatures for each lake during ice-out and the main Group I Isochrysidales bloom (, r2=0.60, RMSE = ±1.69 ∘C; Longo et al., 2018). The calibration for Group I was updated to include additional lakes in northeastern China (, r2=0.48) and now has an RMSE ∘C (Yao et al., 2019). Group I alkenone calibrations also exist for Lake BrayaSø in Greenland (, r2=0.96; note that the calibration also includes data from several German lakes – see Zink et al., 2001; D'Andrea et al., 2011), Lake Kongressvatnet in Svalbard (, r2=0.85, D'Andrea et al., 2012), Toolik Lake in Alaska (, r2=0.85; Longo et al., 2016), and Vikvatnet in Norway (, r2=0.94; D'Andrea et al., 2016).

Temperature calibrations using the index were applied to develop high-resolution records of summer temperatures in Greenland (ca. 5600 yr BP; D'Andrea et al., 2011) and Svalbard (1800 yr BP; D'Andrea et al., 2012 and 12 000 yr BP; van der Bilt et al., 2018, 2019), as well as a winter–spring temperature record in Alaska (16 000 yr BP; Longo et al., 2020). The main timing of ice-out, and the corresponding alkenone bloom in VGHV, occurs in April to May in southern Iceland and May to June in northern Iceland (see Tables A2 and A3). In contrast, studies in Svalbard report ice-out dates between late June to mid-August and show that alkenones primarily record summer (JJA) temperatures (D'Andrea et al., 2012; van der Bilt et al., 2019). In northern Alaska ice-out dates primarily occur in June and reflect temperature changes during the winter and spring season (Longo et al., 2018, 2020). The regional variability in the relationship between the index and temperature as well as differences in the timing of the alkenone bloom requires the development of local temperature calibrations and validation of the seasonal sensitivity of the proxy for each region (Wang and Liu, 2013; D'Andrea et al., 2016; Longo et al., 2016). Unfortunately, there is currently no local calibration for Icelandic lakes, but in the following section we will describe how we use a lake model to test what drives changes in ice-out dates and lake water temperatures, and therefore the seasonality of temperature recorded by alkenones, in VGHV.

2.4 Seasonal temperature sensitivity of Group I alkenones in lakes

In Greenland and Alaska, Group I Isochrysidales bloom during the early spring in the photic zone as lake ice starts to melt (D'Andrea and Huang, 2005; D'Andrea et al., 2011; Longo et al., 2016, 2018). Alkenone production starts prior to ice-out, then increases as the lake undergoes isothermal mixing, and decreases when thermal stratification begins to develop in late spring and early summer (Longo et al., 2018). This holds true for other Group I-containing lakes in the NH, including lakes in Iceland, as evidenced by the positive correlation between the index and mean spring air temperatures (Longo et al., 2018).

We investigated the controls on spring lake water temperatures and the timing of ice melt in VGHV using a lake energy balance model (Dee et al., 2018). The purpose of the lake model was to determine the sensitivity of our proxy to different forcing mechanisms by assessing the temperature response and timing of ice melt relative to our control simulation. Due to the lack of extensive observational datasets from VGHV to test our model, we adjusted the initial parameters using available data in the literature and parameterizations determined by Longo et al. (2020) for lakes in northern Alaska, where the lake model was validated using limnological data from the Toolik Environmental Data Center and the Arctic Long-Term Ecological Research program over a 6-year period (see Table A1). Lake E5 in northern Alaska is similar in size and with a similar catchment area to VGHV (Longo et al., 2020). The neutral drag coefficient was set to 0.002, and the albedos for slush and snow were set to 0.4 and 0.7, respectively. Note that volcanic eruptions in Iceland can result in ash deposits on the snow, lower the albedo of the resulting slush and snow cover on VGHV, and lead to earlier ice-out dates (Landl et al., 2003). However, we expect this to only be important during volcanic eruptions that occurred during the winter and/or spring season and would only influence the lake water temperatures and ice cover during that year. As our purpose is to understand how the lake responds on longer timescales, we keep the values for albedo constant. The model was initialized using ERA-Interim daily data (1979–2018 CE; ECMWF; Dee et al., 2011) averaged over grid cells covering southwest Iceland (63.00–64.50∘ N by 18.25–22.75∘ W for a 0.75∘ × 0.75∘ grid). An initial control simulation was run for 39 years, followed by sensitivity tests where various perturbations were introduced. Results from the control simulation were compared with available meteorological data, ice-out dates from nearby lakes in Iceland, and the few observations we were able to make using satellite imagery when our study site was not obscured by clouds (Tables A2 and A3; Fig. A2). The lack of extensive observational data from VGHV prevents us from validating the outputs from the lake model simulation; therefore we use the outputs from the lake model to highlight what processes could lead to variations in ice-out dates and lake water temperatures during the spring season but not to quantify the number of days or degrees that ice-out dates and temperatures, respectively, changed in the lake over the last 2000 years.

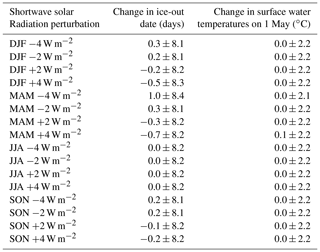

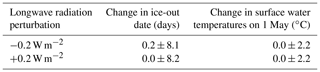

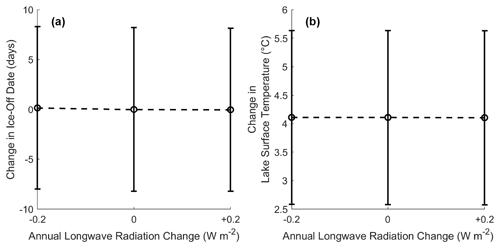

The perturbation experiments focused on the effects of changes in seasonal air temperatures and shortwave and longwave radiation on lake surface temperatures and ice-out dates. We used instrumental data from Hella, Iceland (1958–2005 CE), to determine the magnitude of seasonal air temperature changes (Icelandic Meteorological Office, 2012). Between 1958–2005 the ranges of mean seasonal temperatures are as follows: winter (DJF) −3.7 to 1.8 ∘C, spring (MAM) −1.0 to 6.9 ∘C, summer (JJA) 8.8 to 12.0 ∘C, and fall (SON) −1.3 to 6.7 ∘C. To constrain the seasonality of our proxy, we perturbed the ERA interim seasonal air temperature values by −7, −3, 0, +3, and +7 ∘C and re-ran the lake model with the adjusted parameters. We repeated these experiments but instead perturbed surface incident shortwave radiation to test how external forcings can drive changes in temperature. Incoming (top of the atmosphere) insolation at 63∘ N has increased in winter (DJF) by 1.5 W m−2 and in spring (MAM) by 3.7 W m−2 over the past 2000 years (Laskar et al., 2004). We therefore tested insolation forcing by perturbing seasonal changes in surface incident shortwave radiation by −4, −2, 0, +2, and +4 W m−2. It should be noted that Iceland receives minimal light during the winter months and VGHV is frozen during the winter months, so we expect little to no direct influence of insolation on lake water temperatures during winter. Shortwave radiation values for the winter (DJF) were set to 0 W m−2 if a negative perturbation decreased shortwave radiation below 0 W m−2. To assess the effects of longwave radiation on lake water temperatures and ice-out dates, we decreased and increased incoming longwave radiation by −0.2, 0, and +0.2 W m−2. These values reflect the forcing from well-mixed greenhouse gas (GHG) radiation during the pre-industrial period (Schmidt et al., 2011).

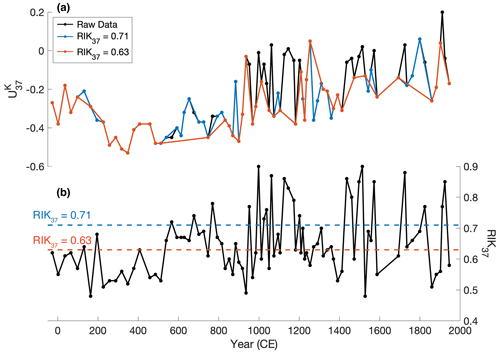

3.1 index: corrections for species mixing

Our index from VGHV suggests that there was substantial variability in temperature during the last 2000 years, but there was also variability in the community of alkenone producers (Fig. 3a). Alkenones in VGHV surface sediments have an RIK37 value of 0.60, and genetic analyses confirm that Group I Isochrysidales is the main alkenone producer (Longo et al., 2018; Richter et al., 2019). However, the RIK37 values increase slightly above the Group I cut-off of 0.63 about ca. 500 CE and then show a more sustained increase after human settlement in Iceland (ca. 870 CE), suggesting that Group II alkenone producers were also present in the lake (Fig. 3b).

Figure 3(a) The raw data for the index is indicated in black, and the corrected index with an RIK37 cut-off of 0.63 and 0.71 is shown in orange and blue, respectively. (b) The original RIK37 index is shown below for comparison with the empirical cut-off, RIK37=0.63, and cut-off for RIK37=0.71 is indicated.

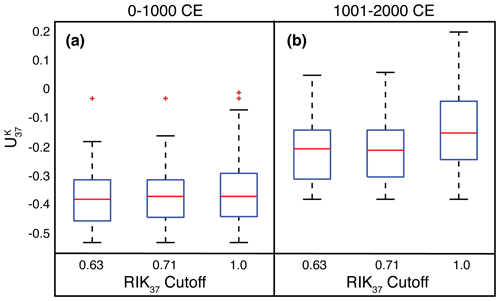

To evaluate the potential impacts of species mixing on the record, samples with a high abundance of Group II alkenones were removed. We tested several different cut-offs for the RIK37 index and compared changes in the mean values (Fig. 4). If no correction is applied (RIK37=1.0), then from 0–1000 CE and from 1001–2000 CE. The empirically defined cut-off of 0.63 yields a mean index of from 0–1000 CE and from 1001–2000 CE. A less stringent RIK37 cut-off at 0.71 results in no significant difference in the mean or the variability of the data (0–1000 CE and 1001–2000 CE ). Species mixing thus affects the temperature record, but regardless of the correction applied to the data, there is an increase in the mean values (which we interpret as warming) from 0–1000 to 1001–2000 CE. To further validate our results, we also did an additional comparison using both the RIK37 and RIK38E indices (Fig. A1). Due to lower abundance of C38:3 Et and its isomer we had fewer data points for comparison, but our results still demonstrate that data points used in our study are predominantly produced by Group I Isochrysidales.

Figure 4Different RIK37 cut-offs applied to the index for (a) 0–1000 CE and (b) 1001–2000 CE. An RIK37 value of 1.0 indicates that the data were not corrected for species-mixing effects, while RIK37=0.63 corresponds to the empirically defined cut-off for groups I and II (Longo et al., 2018).

Using an RIK37 cut-off of 0.71, the corrected values and RIK37 index are not correlated (r=0.11, p=0.35), indicating that species-mixing effects do not affect the final temperature calibration. The resulting values can be interpreted as a record of temperature changes from Group I alkenones.

3.2 Controls on spring lake water temperature

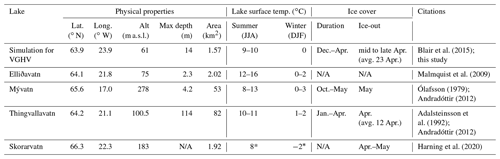

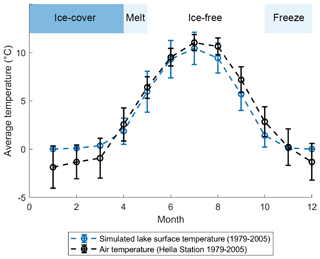

Currently there are no extensive datasets on changes in lake water temperatures and/or ice-out dates for lakes (in particular lakes that are not influenced by geothermal activity or are glacial lakes that are subject to seawater intrusions) in Iceland to validate the control simulation from our lake model. However, a comparison with existing data in the literature and satellite images that were not obscured by cloud cover suggests that the timing of the ice-out dates in our lake model (mid to late April) and mean monthly temperatures of the surface lake water are reasonable (Tables A2 and A3; Fig. A2). We use the results from the lake model to infer what processes could drive large changes in ice-out dates and lake water temperatures and thereby determine the seasonal sensitivity of our proxy.

Results from the lake energy balance model show that seasonal perturbations can have a strong influence on spring lake water temperatures and ice-out dates in VGHV (Fig. 5, Table A4). The control run yields an average ice-out date of 23 April with surface water temperatures on 1 May of 4.1±1.5 ∘C. Air temperature perturbations during the winter (DJF) and spring (MAM) alter the timing of ice-out and how rapidly surface water temperatures warm, with warmer air temperatures leading to warmer water temperatures and earlier ice-out dates (Fig. 5a–b). Changes in shortwave radiation did not have a significant influence on ice-out dates or lake water temperatures; the largest response is observed in spring (MAM) ice-out dates (Fig. 5c–d, Table A5). Shorter days during the winter months (DJF) limit the amount of shortwave radiation reaching Iceland and therefore have a minimal influence on Icelandic temperatures (Fig. 5d). There are no competing effects of summer (JJA) or fall (SON) insolation and air temperatures on spring lake water temperatures and the timing of ice-out. The increase in longwave radiation from GHGs during the pre-industrial period is relatively small and has no significant influence on either lake water temperatures (change from control = 0.0±2.2 ∘C) or ice-out dates (change from control = 0.0±8.1 d; Fig. A3, Table A6). Thus, the timing of the alkenone bloom and the water temperatures recorded by the alkenones are most likely responses to changes in air temperature during the late winter and spring season.

Figure 5Lake model sensitivity tests showing the impacts of air temperature perturbations during different seasons on (a) ice-out dates and (b) lake water temperatures on 1 May. Similarly, the effects of shortwave radiation on (c) ice-out dates and (d) lake water temperatures are shown. Changes in ice-out dates and lake surface temperatures were calculated relative to the control simulation. Seasonal changes are shown for winter (DJF, blue), spring (MAM, purple), summer (JJA, green), and fall (SON, orange).

3.3 Long-term trends and short-term variability in the record and temperature

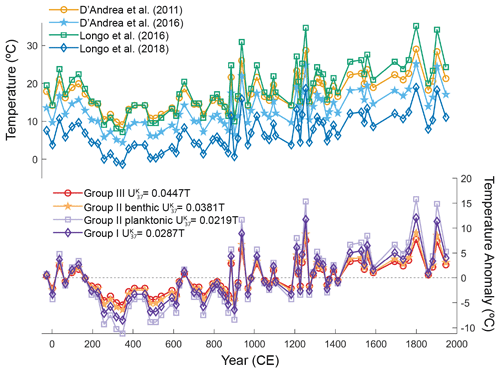

The index can provide temperature estimates using linear relationships that are calibrated in lakes with Group I alkenone producers (D'Andrea et al., 2011, 2016; Longo et al., 2016, 2018). Existing temperature calibrations, except for the Northern Hemisphere calibration by Longo et al. (2018), for Group I are site-specific and therefore cannot be readily applied to VGHV (e.g., calibrations give estimates of 10.2 to 33.5 ∘C (D'Andrea et al., 2011), 7.1 to 34.4 ∘C (Longo et al., 2016), 4.4 to 24.5 ∘C (D'Andrea et al., 2016), −1.4 to 18.3 ∘C (calibration for Northern Hemisphere lakes by Longo et al., 2018; see Fig. A4)). Most of the variation between sites is accounted for by the y intercept of the calibration, so the slope of Group I calibrations was suggested as a better determinant of relative temperature changes for sites lacking a site-specific calibration (D'Andrea et al., 2016). However, the slopes determined for Group I calibrations still result in a very large and likely unreasonable temperature range of 26.9 ∘C for (D'Andrea et al., 2016). The amplitude of the reconstructed temperature is still relatively large considering that each sample is an average of 5–19 years and most likely stems from the lack of a local calibration. These discrepancies are highlighted by the variability observed in the Northern Hemisphere calibration developed by Longo et al. (2018), where only 60 % of the index is explained by temperatures during the spring isotherm. In VGHV, the –temperature relationship could highlight the differences in the sensitivity of VGHV lake water temperatures to air temperature relative to previous studies on Group I Isochrysidales (Longo et al., 2018). Despite these differences, the index is known to be highly sensitive to temperatures in NH lakes, and both the millennial and multi-decadal variabilities in our index exceed the range of our analytical uncertainty. We assume that, after correcting for species mixing, there are no environmental parameters other than temperature that affect our record, and we therefore use the index to infer and evaluate qualitative changes in temperature trends and variability during the past 2000 years.

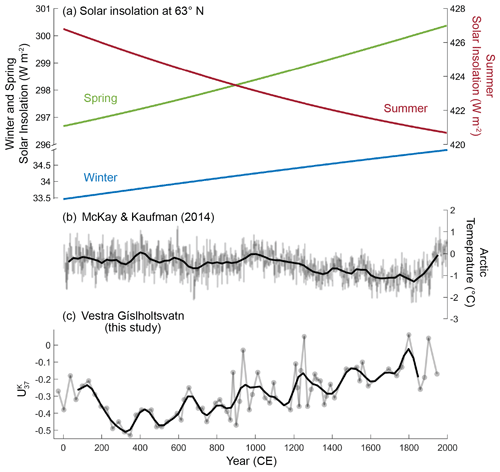

The record from VGHV, corrected for species mixing, exhibits a long-term trend towards warmer spring lake water temperatures over the last 2000 years as well as strong multi-decadal to centennial variability (Fig. 6). The gradual warming trend in our record begins after ca. 400 CE. In particular, a warmer period occurs from the start of our record to ca. 200 CE, followed by a cooler period from ca. 250–600 CE. Temperature variability increases after ca. 850 CE, and warmer periods occur between ca. 850–1050, ca. 1100–1300, and ca. 1450–1550 CE. Relatively cooler periods occur at ca. 1100–1200, ca. 1300–1450, ca. 1550–1750, and ca. 1850–1880 CE. However, caution should be used when interpreting results after ca. 1400 CE because of low sampling resolution (ca. 50 years between each sample).

Figure 6(a) Changes in solar insolation at 63∘ N for winter (DJF), spring (MAM), and summer (JJA) are shown for the past 2000 years (Laskar et al., 2004). In addition, (b) a compilation of Arctic temperature reconstructions (McKay and Kaufman, 2014) is shown for comparison with the (c) winter–spring temperature reconstruction from VGHV. The thick black lines correspond to low-pass filters (every 25 years) applied to the Arctic dataset and VGHV record.

4.1 Regional controls on winter and spring temperatures in southwest Iceland

Results from the lake energy balance model suggest that lake water temperatures during the spring season and the timing of ice-out in VGHV primarily respond to changes in air temperature during the winter and spring season. Air temperatures in southwest Iceland are typically warmer (Vestmannaeyjar mean annual air temperature (MAAT): 4.9±0.6 ∘C for 1878–2002) than in northern Iceland (Grímsey MAAT: 2.3±1.0 ∘C for 1878–2002) due to the advection of the warm Irminger Current along the southern coast and lack of sea ice formation during the winter and spring seasons (Einarsson, 1984; Hanna et al., 2004). Based on our lake model simulation, spring surface water temperatures in VGHV respond to changes during the winter and spring season because the lake re-freezes every winter and reaches minimum lake water temperatures, meaning any influence from the previous summer or fall season is negligible (e.g., Assel and Robertson, 1995). Similar lake model parameterizations were used to simulate spring lake water temperatures in a lake in Alaska, where the lake model was rigorously tested against observational data, and the authors also observed that surface water temperatures during the spring season only respond to air temperature changes during the winter and spring (DJFMAM) seasons (Longo et al., 2020). Further, an increase in winter and spring air temperatures leads to earlier ice-out dates. This is consistent with previous work in Alaska where an increase of 3 ∘C during the winter and spring (DJFMAM) led to an earlier simulated ice-out date by 12 d (Longo et al., 2020). Lake ice-out is expected to occur earlier during years when volcanic ash leads to “dirty” snow and lowers the albedo of the lake ice (Landl et al., 2003); however, this likely has a minimal influence on our record on 10- to 20-year timescales. This suggests that our alkenone proxy is primarily sensitive to changes in air temperatures during the winter and spring season.

The VGHV temperature record shows that winter and spring air temperatures warmed over the last millennium, whereas temperature and sea ice reconstructions suggest that summer air temperatures cooled in northern and western Iceland as sea ice increased and reached a maximum during the 18th and 19th centuries (Ogilvie and Jónsson, 2001; Moros et al., 2006; Massé et al., 2008; Gathorne-Hardy et al., 2009; Axford et al., 2009, 2011; Langdon et al., 2011; Cabedo-Sanz et al., 2016; Holmes et al., 2016). Paleo-records and historical records, however, indicate that sea ice was only present along the southern and western coasts of Iceland, where our study site VGHV is located, during severe ice years when sea ice is advected clockwise around the country (Ogilvie, 1996; Axford et al., 2011; Cabedo-Sanz et al., 2016). Sea ice often leads to enhanced cooling in northern Iceland relative to southern Iceland, leading to a larger temperature gradient and differences in the rate of warming, particularly during the winter and spring months (e.g., from 1871–2001 Grímsey in northern Iceland, which warmed by 1.4 and 0.6 ∘C in winter (DJFM) and spring (AM), respectively, compared to Vestmannaeyjar in southern Iceland warmed by 2.1 and 2.3 ∘C in winter and spring, respectively; Hanna et al., 2004). In contrast to northern Iceland, sea ice is therefore expected to have a smaller impact on air temperatures at our study site over the last 2000 years.

Similar to our record from VGHV, millennial-scale changes in spring temperatures inferred from biogenic silica in western Iceland are decoupled from temperature and sea ice changes in northern Iceland, suggesting that spring temperatures are likely more sensitive to changes in regional sea surface temperatures (SSTs; Geirsdóttir et al., 2009). SST reconstructions near southern Iceland show that surface temperatures either increased (Berner et al., 2008; Thornalley et al., 2009; Miettinen et al., 2012; Orme et al., 2018) or did not significantly change (Sicre et al., 2011; Van Nieuwenhove et al., 2018) over the last 2000 years. Marine reconstructions of temperature from below the summer thermocline and bottom water record a decrease in mean annual temperatures over the Common Era (Thornalley et al., 2009; Ólafsdóttir et al., 2010; Moffa-Sánchez et al., 2014) as the transport of warm North Atlantic waters by the Irminger Current decreased over the last 2000 years (Ólafsdóttir et al., 2010). The differences in proxy records could be related to differences in proxy seasonality. The different seasonal response in SSTs is observed in a gradual increase in winter and decrease in summer temperatures over the Holocene in a marine record from southern Iceland, suggesting that SSTs near southern Iceland are sensitive to both changes in ocean circulation and seasonal insolation (Van Nieuwenhove et al., 2018). As the maritime climate of southern Iceland is sensitive to changes in SSTs, we would therefore expect millennial-scale changes in both ocean circulation and insolation to be reflected in the VGHV temperature record. Based on existing paleo-records and historical records we conclude that sea ice feedbacks play a minor role in driving long-term changes in winter and spring temperatures at our study site, whereas an increase in SSTs along the southern coast could contribute to the warming trend observed in our record.

4.2 Long-term seasonal climate trends in Northern Hemisphere paleoclimate records

Mean annual temperature syntheses from the NH exhibit a long-term cooling trend over the last 2000 years (Kaufman et al., 2009; PAGES 2K Consortium, 2013, 2019) that is often interpreted as a response to decreasing summer insolation (Kaufman et al., 2009) and/or increased volcanic activity during the LIA (Miller et al., 2012). The magnitude of the cooling trend differs among global temperature reconstructions (PAGES 2K Consortium, 2019) and is often larger in NH temperature reconstructions compared to climate model simulations (Rehfeld et al., 2016; Ljungqvist et al., 2019). The discrepancies in temperature reconstructions and climate models could stem from a warm season bias in NH proxy reconstructions, leading to an overestimation of changes in mean annual and cold season temperatures in proxy reconstructions compared to climate model simulations (Liu et al., 2014; Rehfeld et al., 2016; PAGES 2K Consortium, 2019).

The distinct warming trend in the winter–spring temperature reconstruction from VGHV could provide new insights into the mechanisms that influence cold season temperatures in the North Atlantic region. As discussed in the previous section, the maritime climate of southern Iceland and therefore the temperature recorded at our study site reflect variability in seasonal SSTs that are driven by changes in ocean circulation and seasonal insolation. In contrast, mean annual longwave radiative forcing, i.e., GHGs, over the pre-industrial period has a minimal influence on water temperatures and ice-out dates in VGHV. Long-term warming trends over the Holocene and the Common Era were also observed in other records of cold-season temperatures in the NH. For instance, pollen records of cold-season temperatures from North America and Europe (Mauri et al., 2015; Marsicek et al., 2018) and an alkenone reconstruction of winter–spring temperatures from Alaska (Longo et al., 2020) suggest that increasing winter and spring orbital insolation over the Holocene drove warming during the winter and spring season. Winter warming over the Holocene, including the Common Era, was also inferred from chrysophyte cysts in Spain (Pla and Catalan, 2005), ice-wedge records in the Siberian Arctic (Meyer et al., 2015; Opel et al., 2017), and a speleothem record from the Ural Mountains in Russia (Baker et al., 2017). A marine record directly south of Iceland from the North Atlantic subpolar gyre, records winter SSTs that are on average warmer over the last 2000 years relative to the early to mid-Holocene (Van Nieuwenhove et al., 2018). In each of these studies, insolation and/or rising greenhouse gases are proposed as the primary mechanisms driving changes in seasonal temperatures.

Although there are existing reconstructions of NH winter and spring temperatures during the Common Era, the high-resolution reconstruction of winter–spring temperatures from VGHV is one of the few sites in the northern high latitudes where the effects of seasonal insolation on winter and spring temperatures can be tested without having to account for the influence of confounding factors, such as precipitation, on proxy records. For instance, varve thickness records have been interpreted to reflect winter temperatures but might be influenced by human activities in the catchment area, variations in snow accumulation, the timing of spring melt, and changes in precipitation (Ojala and Alenius, 2005; Haltia-Hovi et al., 2007). Varve thickness records from the Arctic that record changes in snow or glacial melt are also used to infer long-term cooling during the melt season; however, the melt season in the high Arctic often extends well into the summer months (Cook et al., 2009; Larsen et al., 2011) and can be affected by Arctic summer hydrology. Water isotope records from ice cores from Svalbard and a stalagmite from the Central Alps are sensitive to winter air temperatures during the instrumental period, but changes in the moisture source and seasonality of precipitation over time can alter long-term temperature interpretations (Isaksson et al., 2005; Mangini et al., 2005; D. Divine et al., 2011; D. V. Divine et al., 2011). Although our record lacks a local calibration, we argue that the record from VGHV provides a robust, albeit qualitative, record of winter–spring temperatures given the unique seasonal growth ecology of Group I haptophytes in NH lakes. The warming trend observed in our record from Iceland and other records of cold-season temperatures from the NH suggest that long-term temperature changes are driven by a common forcing – orbitally driven changes in winter and spring insolation – during the Holocene (Mauri et al., 2015; Meyer et al., 2015; Baker et al., 2017; Marsicek et al., 2018; Van Nieuwenhove et al., 2018; Longo et al., 2020) and during the Common Era (Pla and Catalan, 2005; Meyer et al., 2015; Baker et al., 2017; Opel et al., 2017).

4.3 Multi-decadal to centennial variability in winter–spring temperature in the North Atlantic

The VGHV reconstruction of winter–spring temperatures provides an opportunity to test how changes in internal climate variability and external forcings (volcanic eruptions and total solar irradiance, or TSI) influence temperature changes during the winter and spring seasons in the North Atlantic region on multi-decadal to centennial timescales. The NAO, defined by differences in sea-level pressure between the subpolar low and the subtropical high, is a major source of atmospheric variability during the winter months (Hurrell, 1995). Although the NAO is mainly associated with interannual timescales, there is also evidence that NAO-like patterns can emerge at multi-annual to centennial timescales, potentially linked to coupled changes in oceanic and atmospheric circulation (Visbeck et al., 2003; Delworth et al., 2016; Yeager and Robson, 2017). For instance, a positive (negative) NAO phase that persists for multiple winters can lead to increased (decreased) deepwater formation in the Labrador Sea and strengthening (weakening) of the subpolar gyre (SPG) and the meridional overturning circulation, thereby resulting in an increased (decreased) transport of warm waters towards the poles (Eden and Jung, 2001; Visbeck et al., 2003; Latif et al., 2006; Moffa-Sánchez and Hall, 2017). Alternatively, an increase in the southward transport of polar waters could also result in a reduction of deepwater formation in the Labrador Sea and a weaker SPG, leading to a decrease in northward oceanic heat transport and centennial cooling of ocean and regional air temperatures but warming of SSTs south of Iceland (Moffa-Sánchez and Hall, 2017; Moreno-Chamarro et al., 2017).

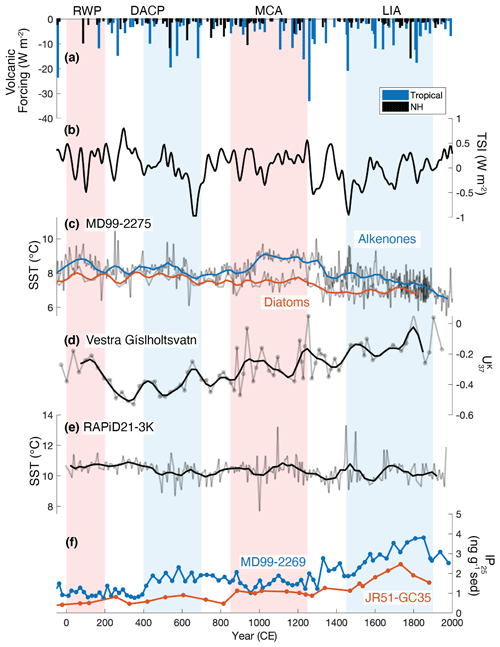

Whether forced or unforced, variability in winter atmospheric circulation, including the NAO, and sea ice extent are often linked to multi-decadal and centennial climate change in the North Atlantic region, particularly over Iceland (e.g., Hanna et al., 2006; Massé et al., 2008; Yeager and Robson, 2017). In the VGHV record of winter–spring temperatures there is a sharp decrease in the index at ca. 250 CE and a corresponding increase in drift ice along the north Icelandic shelf at ca. 400–900 CE (Fig. 7; Moros et al., 2006; Cabedo-Sanz et al., 2016). Cooling during this time period is typically attributed to volcanic eruptions and a minimum in solar activity (ca. 400–700 CE; Fig. 7a–b); however, this cold interval was not uniform across the NH and records differ as to when peak cooling occurred (Helama et al., 2017). For instance, a colder interval is observed in a marine SST record from the south of Iceland from ca. 200–400 CE, whereas there is no distinct or prolonged cooling in SST records from the north Icelandic shelf (Fig. 7c; Sicre et al., 2008; Jiang et al., 2015) or in summer temperature records from Icelandic lakes (Gathorne-Hardy et al., 2009; Axford et al., 2009). In contrast, terrestrial records from the Arctic and northern Europe indicate that temperatures were on average cooler between ca. 450–700 and ca. 500–650 CE, respectively (Kaufman et al., 2009; Sigl et al., 2015; Helama et al., 2017). The heterogenous temperature response in the North Atlantic region could be associated with a strengthening of the SPG between ca. 200–400 CE, resulting in increased oceanic meridional heat transport to northern Europe and colder SSTs near southern Iceland (Miettinen et al., 2012; Moffa-Sánchez and Hall, 2017). After ca. 400 CE there is evidence of increased salinity and warming SSTs south of Iceland that are associated with a gradual weakening of the SPG and contributed to a return to warmer temperatures in our VGHV record (Thornalley et al., 2009; Moffa-Sánchez and Hall, 2017; Moreno-Chamarro et al., 2017). A weaker SPG after ca. 400 CE would also result in cooler Nordic waters and contribute to the cooler climate conditions observed in northern Europe at ca. 500–650 CE (Miettinen et al., 2012; Helama et al., 2017; Moffa-Sánchez and Hall, 2017).

Figure 7Major changes in radiative forcings over the past 2000 years are shown, including (a) volcanic forcing from tropical and NH eruptions (Sigl et al., 2015) and (b) changes in total solar irradiance (TSI; Steinhilber et al., 2009). Marine and terrestrial reconstructions from Iceland are shown, including (c) alkenone and diatom sea surface temperature (SST) reconstructions from core MD99-2275 on the north Icelandic shelf (Sicre et al., 2008; Jiang et al., 2015), (d) an alkenone winter–spring temperature reconstruction from VGHV in southwest Iceland (this study), (e) an alkenone SST record from core RAPiD21-3K in the subpolar North Atlantic (Sicre et al., 2011), and (f) sea ice reconstructions developed using IP25 from cores MD99-2269 (blue) and JR51-GC35 (orange) from the north Icelandic shelf (Cabedo-Sanz et al., 2016). The timing of major climate anomalies inferred from Icelandic climate records include the Roman Warm Period (RWP, ca. 0–200 CE), Dark Ages Cold Period (DACP, ca. 400–700 CE), Medieval Climate Anomaly (MCA, ca. 850–1250 CE), and Little Ice Age (LIA, ca. 1450–1900 CE).

Winter and spring temperatures in VGHV were on average higher between ca. 880–1100 CE than temperatures during the Dark Ages Cold Period but were not stable or particularly warm, unlike the climate usually associated with the Norse settlement of Iceland between ca. 870–1100 CE (Fig. 7; Ogilvie et al., 2000). This time period corresponds to a peak in TSI and weak volcanic activity (PAGES 2K Consortium, 2013) and warmer summer and annual SSTs near northern and southern Iceland (Sicre et al., 2008, 2011; Justwan et al., 2008; Ran et al., 2011). Summer temperature reconstructions from lakes in northern and western Iceland also record warmer temperatures at ca. 800–1300 CE but with distinct cold excursions occurring between ca. 1000–1300 CE (Axford et al., 2009; Gathorne-Hardy et al., 2009; Holmes et al., 2016). Peaks in sea ice, however, are only noted after ca. 1200 CE (Ogilvie, 1992; Ogilvie and Jónsson, 2001; Massé et al., 2008; Cabedo-Sanz et al., 2016), suggesting that an alternative mechanism, such as the NAO, may be responsible for the short-term variability observed in terrestrial temperature records from Iceland during this time period.

The 14th–15th centuries mark the start of the LIA and are often associated with a colder-than-average climate in Iceland (Ogilvie, 1984; Ogilvie and Jónsson, 2001). In contrast, the VGHV record indicates there was no prolonged cold period during the winter and spring season at our study site between ca. 1300–1800 CE, which could indicate a continued response to the warming observed in SSTs south of Iceland (Thornalley et al., 2009; Miettinen et al., 2012). Cooling during this time period is associated with major volcanic eruptions and decreases in TSI (PAGES 2K Consortium, 2013; Otto-Bliesner et al., 2016) that led to an increase in sea ice (Fig. 7; Moros et al., 2006; Massé et al., 2008; Cabedo-Sanz et al., 2016) and cooling of summer and annual SSTs between ca. 1400–1900 CE along the north Icelandic shelf (Fig. 7c and e; Jiang et al., 2005, 2015; Sicre et al., 2008; Ran et al., 2011). A record of subsurface winter temperatures inferred from glycerol dialkyl glycerol tetraethers (GDGTs) along the north Icelandic shelf also shows cold excursions between 1200–1900 CE, with increased sea ice cover that resulted in insulation-induced warming between ca. 1550–1750 CE (Harning et al., 2019). The inconsistent response in VGHV temperatures to volcanic eruptions and solar minima between ca. 1300–1800 CE could be associated with stochastic climate processes, such as the NAO, or a continued weakening of the SPG that counteracted the effects of negative radiative forcings and led to winter and spring warming over southern Iceland rather than cooling as observed in northern Iceland.

On multi-decadal to centennial timescales, changes in the VGHV record do not consistently correspond to major temperature anomalies observed during the summer months. The differences in seasonal climate responses to external forcings imply that the regional manifestation of these events depends on the initial state of the atmosphere and ocean but that it is also modulated by internal climate variability and changes in SSTs near southern Iceland associated with the SPG.

The most striking feature of the VGHV record of winter–spring temperatures is a long-term warming trend from ca. 250 CE to the present. Gradual warming in winter and spring temperatures is most likely associated with gradual warming of SSTs near southern Iceland that are responding to increasing winter and spring solar insolation over the last 2000 years. This contrasts with inferences of mean annual and summer time warming elsewhere in the NH. On multi-decadal to centennial timescales winter–spring temperatures respond to strong radiative forcings, but regional temperature responses are often masked by internal climate variability or changes in ocean circulation. These processes can cause regional differences in temperature and strong contrasts between winter and spring, summer, and mean annual temperatures. In general, this highlights a need for more winter and spring temperature reconstructions to improve our understanding of the magnitude and direction of cold-season temperature changes over the Common Era.

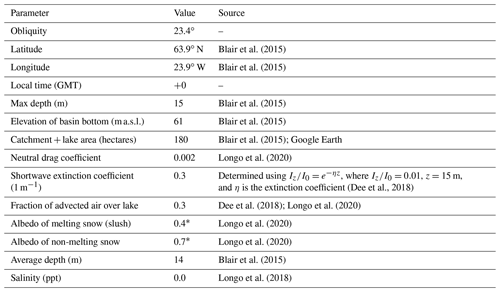

Table A1Lake-specific parameters for the model setup and references used to constrain the parameters.

* Note: the albedo will be lower if there was a volcanic eruption that led to “dirty” snow and/or slush (Landl et al., 2003).

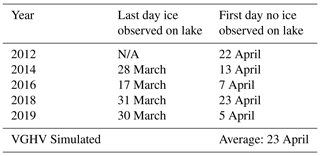

Table A2Outputs for lake model simulation and comparison with available observational data from Iceland (where N/A means not available).

* Note: Skorarvatn temperatures are air temperatures that were based on a nearby meteorological station (Æðey) and were adjusted using the lapse rate for Skorarvatn.

Table A3Ice-out dates determined using satellite imagery (Planet Labs Inc.). Due to cloud cover we could not determine the exact dates of ice-out. We recorded the last day we observed ice on VGHV and the first day when we were able to observe VGHV as being completely ice-free.

Table A4Results from the lake energy balance model for air temperature perturbations showing the change in ice-out dates and lake water temperatures relative to the control simulation (average ice-out date: 23 April ± 6 d; average lake water temperature: 4.1±1.5 ∘C).

Table A5Results from the lake energy balance model for shortwave radiation perturbations showing the change in ice-out dates and lake water temperatures relative to the control simulation (average ice-out date: 23 April ± 6 d; average lake water temperature: 4.1 ± 1.5 ∘C).

Table A6Results from the lake energy balance model for longwave radiation perturbations showing the change in ice-out dates and lake water temperatures relative to the control simulation (average ice-out date: 23 April ± 6 d; average lake water temperature: 4.1 ± 1.5 ∘C).

Figure A1Comparison of RIK37 and RIK38E values for different alkenone distributions. Group I alkenone values (blue) and a mixed sample containing groups I and II (orange) are from the Northern Hemisphere and northern Alaska datasets (Longo et al., 2016, 2018). The values for groups II and III were determined from cultures (see Longo et al., 2018). The original VGHV alkenone distributions are indicated by an X (these points only include samples where we were able to reliably identify and quantify C38:3Et and its isomer). The VGHV alkenones that were corrected for Group II are shown in green.

Figure A2Comparison of simulated lake surface water temperatures for VGHV (blue) and air temperatures from a nearby meteorological station (Hella Station) for the period of 1979–2005. The average duration of ice cover simulated in our lake model is shown in dark blue. The average timing of ice-out dates and the timing of when lake ice cover starts to form that is simulated in our lake model are shown in pale blue.

Figure A3Lake model sensitivity tests showing the effect of annual longwave radiation perturbations on (a) ice-out dates and (b) lake water temperatures on 1 May.

Figure A4Alkenone calibrations from previous studies including (a) (D'Andrea et al., 2011), (D'Andrea et al., 2016), (Longo et al., 2016), and (Longo et al., 2018). (b) Temperature anomalies calculated from slopes previously determined by D'Andrea et al. (2016) for Group III, Group II benthic, Group II planktonic, and Group I.

Data will be made available at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration National Centers for Environmental Information (NOAA NCEI) Paleoclimate Database: https://www.ncdc.noaa.gov/paleo/study/29992 (Richter et al., 2021). The age model and information about the lake sediment core were obtained from https://doi.org/10.1002/jqs.2780 (Blair et al., 2015). The lake energy balance model used in this study was developed by Dee et al. (2018; https://doi.org/10.1029/2018PA003413), and the code developed by Dee et al. (2018) is available at https://github.com/sylvia-dee/PRYSM (last access: 14 April 2021). ERA-Interim daily data (1979–2019 CE) were obtained from https://www.ecmwf.int/en/forecasts/datasets/reanalysis-datasets/era-interim (ECMWF; Dee et al., 2011). Meteorological data for southwest Iceland were obtained from https://en.vedur.is/climatology/data/ (Icelandic Meteorological Office, 2012). Data used to make the maps in Fig. 1 can be found at Natural Earth (https://www.naturalearthdata.com/downloads/10m-physical-vectors/, Natural Earth, 2018), the National Land Survey of Iceland (https://www.lmi.is/is/landupplysingar/gagnagrunnar/nidurhal, National Land Survey of Iceland, 2020), and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) World Ocean Database (https://www.nodc.noaa.gov/OC5/WOD/pr_wod.html; Boyer et al., 2018). Satellite imagery for Table A3 was obtained from Planet Labs Inc. (https://www.planet.com/, Planet Labs Inc., 2021).

The study was conceptualized by NR, JMR, and YH. Method development and laboratory analyses were carried out by NR and JG. NR prepared the paper with contributions from all co-authors.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

We would like to thank Timothy D. Herbert, Rebecca Rose, Jeffrey M. Salacup, Gabriella Weiss, Carrie Morrill, Ashling Neary, Sylvia G. Dee, and Ethan Kyzivat for advice and analytical support. All of the samples for this project were obtained from LacCore (National Lacustrine Core Facility), Department of Earth Sciences, University of Minnesota Twin Cities. We would also like to thank the reviewers and David Harning for helping to improve this paper.

This project was funded by Geological Society of America Graduate Student Research Grants, funding through the Brown University Graduate School, and Brown University Undergraduate Teaching and Research Awards.

This paper was edited by Bjørg Risebrobakken and reviewed by two anonymous referees.

Adalsteinsson, H., Jónasson, P. M., and Rist, S.: Physical characteristics of Thingvallavatn, Iceland. Oikos, 64, 121–135, https://doi.org/10.2307/3545048, 1992.

Andradóttir H. Ó.: Icelandic Lakes, Physical Characteristics, in: Encyclopedia of Lakes and Reservoirs. Encyclopedia of Earth Sciences Series, edited by: Bengtsson, L., Herschy, R. W., Fairbridge, R. W., Springer, Dordrecht, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4020-4410-6_224, 2012.

Assel, R. A. and Robertson, D. M.: Changes in winter air temperatures near Lake Michigan, 1851–1993, as determined from regional lake-ice records, Limnol. Oceanogr., 40, 165–176, https://doi.org/10.4319/lo.1995.40.1.0165, 1995.

Axford, Y., Geirsdóttir, A., Miller, G. H., and Langdon, P. G.: Climate of the Little Ice Age and the past 2000 years in northeast Iceland inferred from chironomids and other lake sediment proxies, J. Paleolimnol., 41, 7–24, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10933-008-9251-1, 2009.

Axford, Y., Andresen, C. S., Andrews, J. T., Belt, S. T., Geirsdóttir, Á., Massé, G., Miller, G. H., Ólafsdóttir, S., and Vare, L. L.: Do paleoclimate proxies agree? A test comparing 19 late Holocene climate and sea-ice reconstructions from Icelandic marine and lake sediments, J. Quat. Sci., 26, 645–656, https://doi.org/10.1002/jqs.1487, 2011.

Baker, J. L., Lachniet, M. S., Chervyatsova, O., Asmerom, Y., and Polyak, V. J.: Holocene warming in western continental Eurasia driven by glacial retreat and greenhouse forcing, Nat. Geosci., 10, 430–435, https://doi.org/10.1038/ngeo2953, 2017.

Berner, K. S., Koç, N., Divine, D., Godtliebsen, F., and Moros, M.: A decadal-scale Holocene sea surface temperature record from the subpolar North Atlantic constructed using diatoms and statistics and its relation to other climate parameters, Paleoceanography, 23, PA2210, https://doi.org/10.1029/2006PA001339, 2008.

Blaauw, M.: Methods and code for `classical' age-modelling of radiocarbon sequences, Quat. Geochronol., 5, 512–518, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quageo.2010.01.002, 2010.

Blair, C. L., Geirsdóttir, Á., and Miller, G. H.: A high-resolution multi-proxy lake record of Holocene environmental change in southern Iceland, J. Quat. Sci., 30, 281–292, https://doi.org/10.1002/jqs.2780, 2015.

Boyer, T. P., Baranova, O. K., Coleman, C., Garcia, H. E., Grodsky, A., Locarnini, R. A., Mishonov, A. V., O’Brien, T. D., Paver, C. R., Reagan, J. R., Seidov, D., Smolyar, I. V., Weathers, K., and Zweng, M. M.: World Ocean Database 2018, edited by: Mishonov, A. V., Technical Edn., NOAA Atlas NESDIS 87, available at: https://www.nodc.noaa.gov/OC5/WOD/pr_wod.html (last access: 24 June 2020), 2018.

Brassell, S. C., Eglinton, G., Marlowe, I. T., Pflaumann, U., and Sarnthein, M.: Molecular stratigraphy: a new tool for climatic assessment, Nature, 320, 129–133, https://doi.org/10.1038/320129a0, 1986.

Cabedo-Sanz, P., Belt, S. T., Jennings, A. E., Andrews, J. T., and Geirsdóttir, Á.: Variability in drift ice export from the Arctic Ocean to the North Icelandic Shelf over the last 8000 years: a multi-proxy evaluation, Quat. Sci. Rev., 146, 99–115, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2016.06.012, 2016.

Christensen, C. L.: Multi-proxy responses of Icelandic lakes to Holocene tephra perturbations, Doctoral dissertation, University of Colorado at Boulder, Boulder, USA, 2013.

Conte, M. H., Sicre, M. A., Rühlemann, C., Weber, J. C., Schulte, S., Schulz-Bull, D., and Blanz, T.: Global temperature calibration of the alkenone unsaturation index () in surface waters and comparison with surface sediments, Geochem. Geophy. Geosy., 7, Q02005, https://doi.org/10.1029/2005GC001054, 2006.

Coolen, M. J., Muyzer, G., Rijpstra, W. I. C., Schouten, S., Volkman, J. K., and Damsté, J. S. S.: Combined DNA and lipid analyses of sediments reveal changes in Holocene haptophyte and diatom populations in an Antarctic lake, Earth Planet. Sci. Lett., 223, 225–239, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2004.04.014, 2004.

Cook, T. L., Bradley, R. S., Stoner, J. S., and Francus, P.: Five thousand years of sediment transfer in a high arctic watershed recorded in annually laminated sediments from Lower Murray Lake, Ellesmere Island, Nunavut, Canada, J. Paleolimnol., 41, 77, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10933-008-9252-0, 2009.

D'Andrea, W. J. and Huang, Y.: Long chain alkenones in Greenland lake sediments: Low δ13C values and exceptional abundance, Org. Geochem., 36, 1234–1241, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.orggeochem.2005.05.001, 2005.

D'Andrea, W. J., Liu, Z., Alexandre, M. D. R., Wattley, S., Herbert, T. D., and Huang, Y.: An efficient method for isolating individual long-chain alkenones for compound-specific hydrogen isotope analysis, Anal. Chem., 79, 3430–3435, https://doi.org/10.1021/ac062067w, 2007.

D'Andrea, W. J., Huang, Y., Fritz, S. C., and Anderson, N. J.: Abrupt Holocene climate change as an important factor for human migration in West Greenland, P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 108, 9765–9769, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1101708108, 2011.

D'Andrea, W. J., Vaillencourt, D. A., Balascio, N. L., Werner, A., Roof, S. R., Retelle, M., and Bradley, R. S.: Mild Little Ice Age and unprecedented recent warmth in an 1800 year lake sediment record from Svalbard, Geology, 40, 1007–1010, https://doi.org/10.1130/G33365.1, 2012.

D'Andrea, W. J., Theroux, S., Bradley, R. S., and Huang, X.: Does phylogeny control -temperature sensitivity? Implications for lacustrine alkenone paleothermometry, Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta, 175, 168–180, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gca.2015.10.031, 2016.

Dee, D. P., Uppala, S. M., Simmons, A. J., Berrisford, P., Poli, P., Kobayashi, S., Andrae, U., Balmaseda, M. A., Balsamo, G., Bauer, P., Bechtold, P., Beljaars, A. C. M., van de Berg, L., Bidlot, J., Bormann, N., Delsol, C., Dragani, R., Fuentes, M., Geer, A. J., Haimberger, L., Healy, S. B., Hersbach, H., Hólm, E. V., Isaksen, L., Kållberg, P., Köhler, M., Matricardi, M., McNally, A. P., Monge-Sanz, B. M., Morcrette, J. J., Park, B. K., Peubey, C., de Rosnay, P., Tavolato, C., Thépaut, J. N., and Vitart, F.: The ERA-Interim reanalysis: configuration and performance of the data assimilation system, Q. J. Roy. Meteor. Soc., 137, 553–597, https://doi.org/10.1002/qj.828, 2011 (data available at: https://www.ecmwf.int/en/forecasts/datasets/reanalysis-datasets/era-interim, last access: 24 June 2020).

Dee, S. G., Russell, J. M., Morrill, C., Chen, Z., and Neary, A.: PRYSM v2.0: A Proxy System Model for Lacustrine Archives, Paleoceanogr. Paleocl., 33,

1250–1269, https://doi.org/10.1029/2018PA003413, 2018.

Delworth, T. L., Zeng, F., Vecchi, G. A., Yang, X., Zhang, L. and Zhang, R.: The North Atlantic Oscillation as a driver of rapid climate change in the Northern Hemisphere, Nat. Geosci., 9, 509–512, https://doi.org/10.1038/ngeo2738, 2016.

Divine, D., Isaksson, E., Martma, T., Meijer, H. A., Moore, J., Pohjola, V., van de Wal, R. S., and Godtliebsen, F.: Thousand years of winter surface air temperature variations in Svalbard and northern Norway reconstructed from ice-core data, Polar Res., 30, 7379, https://doi.org/10.3402/polar.v30i0.7379, 2011.

Divine, D. V., Sjolte, J., Isaksson, E., Meijer, H. A. J., Van De Wal, R. S. W., Martma, T., Pohjola, V., Sturm, C., and Godtliebsen, F.: Modelling the regional climate and isotopic composition of Svalbard precipitation using REMOiso: a comparison with available GNIP and ice core data, Hydrol. Process., 25, 3748–3759, https://doi.org/10.1002/hyp.8100, 2011.

Eden, C. and Jung, T.: North Atlantic interdecadal variability: oceanic response to the North Atlantic Oscillation (1865–1997), J. Climate, 14, 676–691, https://doi.org/10.1175/1520-0442(2001)014<0676:NAIVOR>2.0.CO;2, 2001.

Einarsson, M. Á.: Climate of Iceland, World Survey of Climatology, 15, 673–697, 1984.

Gathorne-Hardy, F. J., Erlendsson, E., Langdon, P. G., and Edwards, K. J.: Lake sediment evidence for late Holocene climate change and landscape erosion in western Iceland, J. Paleolimnol., 42, 413–426, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10933-008-9285-4, 2009.

Geirsdóttir, Á., Miller, G. H., Thordarson, T., and Ólafsdóttir, K. B.: A 2000 year record of climate variations reconstructed from Haukadalsvatn, West Iceland, J. Paleolimnol., 41, 95–115, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10933-008-9253-z, 2009.

Geirsdóttir, Á., Miller, G. H., Andrews, J. T., Harning, D. J., Anderson, L. S., Florian, C., Larsen, D. J., and Thordarson, T.: The onset of neoglaciation in Iceland and the 4.2 ka event, Clim. Past, 15, 25–40, https://doi.org/10.5194/cp-15-25-2019, 2019.

Haltia-Hovi, E., Saarinen, T., and Kukkonen, M.: A 2000-year record of solar forcing on varved lake sediment in eastern Finland. Quat. Sci. Rev., 26, 678–689, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2006.11.005, 2007.

Hanna, E., Jónsson, T., and Box, J. E.: An analysis of Icelandic climate since the nineteenth century, Int. J. Climatol., 24, 1193–1210, https://doi.org/10.1002/joc.1051, 2004.

Hanna, E., Jónsson, T., Ólafsson, J., and Valdimarsson, H.: Icelandic coastal sea surface temperature records constructed: putting the pulse on air–sea–climate interactions in the northern North Atlantic. Part I: comparison with HadISST1 open-ocean surface temperatures and preliminary analysis of long-term patterns and anomalies of SSTs around Iceland, J. Climate, 19, 5652–5666, https://doi.org/10.1175/JCLI3933.1, 2006.

Harning, D. J., Andrews, J. T., Belt, S. T., Cabedo-Sanz, P., Geirsdóttir, Á., Dildar, N., Miller, G. H. and Sepúlveda, J.: Sea Ice Control on Winter Subsurface Temperatures of the North Iceland Shelf During the Little Ice Age: A TEX86 Calibration Case Study, Paleoceanogr. Paleocl., 34, 1006–1021, https://doi.org/10.1029/2018PA003523, 2019.

Harning, D. J., Curtin, L., Geirsdóttir, Á., D'Andrea, W. J., Miller, G. H., and Sepúlveda, J.: Lipid biomarkers quantify Holocene summer temperature and ice cap sensitivity in Icelandic lakes, Geophys. Res. Lett., 47, e2019GL085728, https://doi.org/10.1029/2019GL085728, 2020.

Helama, S., Jones, P. D., and Briffa, K. R.: Dark Ages Cold Period: A literature review and directions for future research, Holocene, 27, 1600–1606, https://doi.org/10.1177/0959683617693898, 2017.

Holmes, N., Langdon, P. G., Caseldine, C. J., Wastegård, S., Leng, M. J., Croudace, I. W., and Davies, S. M.: Climatic variability during the last millennium in Western Iceland from lake sediment records, Holocene, 26, 756–771, https://doi.org/10.1177/0959683615618260, 2016.

Hurrell, J. W.: Decadal trends in the North Atlantic Oscillation: regional temperatures and precipitation, Science, 269, 676–679, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.269.5224.676, 1995.

Icelandic Meteorological Office: Homepage, available at: https://en.vedur.is/climatology/data/ (last access: 11 June 2020), 2012.

Isaksson, E., Divine, D., Kohler, J., Martma, T., Pohjola, V., Motoyama, H., and Watanabe, O.: Climate oscillations as recorded in Svalbard ice core ω18O records between ad 1200 and 1997, Geogr. Ann. A., 87, 203–214, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0435-3676.2005.00253.x, 2005.

Jiang, H., Eiríksson, J., Schulz, M., Knudsen, K. L., and Seidenkrantz, M. S.: Evidence for solar forcing of sea-surface temperature on the North Icelandic Shelf during the late Holocene, Geology, 33, 73–76, https://doi.org/10.1130/G21130.1, 2005.

Jiang, H., Muscheler, R., Björck, S., Seidenkrantz, M. S., Olsen, J., Sha, L., Sjolte, J., Eiríksson, J., Ran, L., Knudsen, K. L., and Knudsen, M. F.: Solar forcing of Holocene summer sea-surface temperatures in the northern North Atlantic, Geology, 43, 203–206, https://doi.org/10.1130/G36377.1, 2015.

Justwan, A., Koç, N., and Jennings, A. E.: Evolution of the Irminger and East Icelandic Current systems through the Holocene, revealed by diatom-based sea surface temperature reconstructions, Quat. Sci. Rev., 27, 1571–1582, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2008.05.006, 2008.

Kaufman, D. S., Schneider, D. P., McKay, N. P., Ammann, C. M., Bradley, R. S., Briffa, K. R., Miller, G. H., Otto-Bliesner, B. L., Overpeck, J. T., Vinther, B. M., and Lakes, A.: Recent warming reverses long-term Arctic cooling, Science, 325, 1236–1239, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1173983, 2009.

Landl, B., Björnsson, H., and Kuhn, M.: The energy balance of calved ice in Lake Jökulsarlón, Iceland, Arct. Antarct. Alp. Res., 35, 475–481, 2003.

Langdon, P. G., Caseldine, C. J., Croudace, I. W., Jarvis, S., Wastegård, S., and Crowford, T. C.: A chironomid-based reconstruction of summer temperatures in NW Iceland since AD 1650, Quat. Res., 75, 451–460, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yqres.2010.11.007, 2011.

Larsen, D. J., Miller, G. H., Geirsdóttir, Á., and Thordarson, T.: A 3000-year varved record of glacier activity and climate change from the proglacial lake Hvítárvatn, Iceland, Quat. Sci. Rev., 30, 2715–2731, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2011.05.026, 2011.

Larsen, G. and Eiríksson, J.: Late Quaternary terrestrial tephrochronology of Iceland – frequency of explosive eruptions, type and volume of tephra deposits, J. Quat. Sci., 23, 109–120, https://doi.org/10.1002/jqs.1129, 2008.

Laskar, J., Robutel, P., Joutel, F., Gastineau, M., Correia, A. C. M., and Levrard, B.: A long-term numerical solution for the insolation quantities of the Earth, Astron. Astrophys., 428, 261–285, https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361:20041335, 2004.

Latif, M., Böning, C., Willebrand, J., Biastoch, A., Dengg, J., Keenlyside, N., Schweckendiek, U., and Madec, G.: Is the Thermohaline Circulation Changing?, J. Climate, 19, 4631–4637, https://doi.org/10.1175/JCLI3876.1, 2006.

Liu, Z., Zhu, J., Rosenthal, Y., Zhang, X., Otto-Bliesner, B. L., Timmermann, A., Smith, R. S., Lohmann, G., Zheng, W., and Timm, O. E.: The Holocene temperature conundrum, P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 111, E3501–E3505, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1407229111, 2014.

Ljungqvist, F. C., Zhang, Q., Brattström, G., Krusic, P. J., Seim, A., Li, Q., Zhang, Q., and Moberg, A.: Centennial-Scale Temperature Change in Last Millennium Simulations and Proxy-Based Reconstructions, J. Climate, 32, 2441–2482, https://doi.org/10.1175/JCLI-D-18-0525.1, 2019.

Longo, W. M., Theroux, S., Giblin, A. E., Zheng, Y., Dillon, J. T., and Huang, Y.: Temperature calibration and phylogenetically distinct distributions for freshwater alkenones: evidence from northern Alaskan lakes, Geochim. Cosmochim. Ac., 180, 177–196, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gca.2016.02.019, 2016.

Longo, W. M., Huang, Y., Yao, Y., Zhao, J., Giblin, A. E., Wang, X., Zech, R., Haberzettl, T., Jardillier, L., Toney, J., and Liu, Z.: Widespread occurrence of distinct alkenones from Group I haptophytes in freshwater lakes: Implications for paleotemperature and paleoenvironmental reconstructions, Earth Planet. Sci. Lett., 492, 239–250, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2018.04.002, 2018.

Longo, W. M., Huang, Y., Russell, J. M., Morrill, C., Daniels, W. C., Giblin, A. E., and Crowther, J.: Insolation and greenhouse gases drove Holocene winter and spring warming in Arctic Alaska, Quat. Sci. Rev., 242, 106438, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2020.106438, 2020.

Malmquist, H. J., Antonsson, Þ., Ingvason, H. R., Ingimarsson, F., and Arnason, F.: Salmonid fish and warming of shallow Lake Elliðavatn in Southwest Iceland, Verh. Internat. Verein. Limnol., 30, 1127–1132, https://doi.org/10.1080/03680770.2009.11902317, 2009.

Mangini, A., Spötl, C., and Verdes, P.: Reconstruction of temperature in the Central Alps during the past 2000 yr from a δ18O stalagmite record, Earth Planet. Sci. Lett., 235, 741–751, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2005.05.010, 2005.

Marsicek, J., Shuman, B. N., Bartlein, P. J., Shafer, S. L., and Brewer, S.: Reconciling divergent trends and millennial variations in Holocene temperatures, Nature, 554, 92–96, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature25464, 2018.

Massé, G., Rowland, S. J., Sicre, M. A., Jacob, J., Jansen, E., and Belt, S. T.: Abrupt climate changes for Iceland during the last millennium: evidence from high resolution sea ice reconstructions, Earth Planet. Sci. Lett., 269, 565–569, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2008.03.017, 2008.

Mauri, A., Davis, B. A. S., Collins, P. M., and Kaplan, J. O.: The climate of Europe during the Holocene: a gridded pollen-based reconstruction and its multi-proxy evaluation, Quat. Sci. Rev., 112, 109–127, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2015.01.013, 2015.

McKay, N. P., and Kaufman, D. S.: An extended Arctic proxy temperature database for the past 2,000 years, Sci. Data, 1, 140026, https://doi.org/10.1038/sdata.2014.26, 2014.

Meyer, H., Opel, T., Laepple, T., Dereviagin, A. Y., Hoffmann, K. and Werner, M.: Long-term winter warming trend in the Siberian Arctic during the mid- to late Holocene, Nat. Geosci., 8, 122–125, https://doi.org/10.1038/ngeo2349, 2015.

Miettinen, A., Divine, D., Koç, N., Godtliebsen, F., and Hall, I. R.: Multicentennial variability of the sea surface temperature gradient across the subpolar North Atlantic over the last 2.8 kyr, J. Climate, 25, 4205–4219, https://doi.org/10.1175/JCLI-D-11-00581.1, 2012.

Miller, G. H., Geirsdóttir, Á., Zhong, Y., Larsen, D. J., Otto-Bliesner, B. L., Holland, M. M., Bailey, D. A., Refsnider, K. A., Lehman, S. J., Southon, J. R. and Anderson, C.: Abrupt onset of the Little Ice Age triggered by volcanism and sustained by sea-ice/ocean feedbacks, Geophys. Res. Lett., 39, L02708, https://doi.org/10.1029/2011GL050168, 2012.

Moffa-Sánchez, P., Born, A., Hall, I. R., Thornalley, D. J., and Barker, S.: Solar forcing of North Atlantic surface temperature and salinity over the past millennium, Nat. Geosci., 7, 275–278, https://doi.org/10.1038/ngeo2094, 2014.

Moffa-Sánchez, P. and Hall, I. R.: North Atlantic variability and its links to European climate over the last 3000 years, Nat. Commun., 8, 1726, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-017-01884-8, 2017.

Moreno-Chamarro, E., Zanchettin, D., Lohmann, K., Luterbacher, J., and Jungclaus, J.: H. Winter amplification of the European Little Ice Age cooling by the subpolar gyre, Sci. Rep., 7, 9981, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-07969-0, 2017.

Moros, M., Andrews, J. T., Eberl, D. D., and Jansen, E.: Holocene history of drift ice in the northern North Atlantic: Evidence for different spatial and temporal modes, Paleoceanography, 21, PA2017, https://doi.org/10.1029/2005PA001214, 2006.

Müller, P. J., Kirst, G., Ruhland, G., Von Storch, I., and Rosell-Melé, A.: Calibration of the alkenone paleotemperature index based on core-tops from the eastern South Atlantic and the global ocean (60∘ N–60∘ S), Geochim. Cosmochim. Ac., 62, 1757–1772, https://doi.org/10.1029/2005GC001054, 1998.

Nakamura, H., Sawada, K., Araie, H., Suzuki, I., and Shiraiwa, Y.: Long chain alkenes, alkenones and alkenoates produced by the haptophyte alga Chrysotila lamellosa CCMP1307 isolated from a salt marsh, Org. Geochem., 66, 90–97, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.orggeochem.2013.11.007, 2014.

National Land Survey of Iceland: Homepage, available at: https://www.lmi.is/is/landupplysingar/gagnagrunnar/nidurhal, last access: 24 June 2020.

Natural Earth: Homepage, available at: https://www.naturalearthdata.com/ (last access: 24 June 2020), 2018.

Ogilvie, A. E. J.: The past climate and sea-ice record from Iceland, Part 1: Data to AD 1780, Climatic Change, 6, 131–152, https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00144609, 1984.

Ogilvie, A. E. J.: Documentary evidence for changes in the climate of Iceland AD 1500 to 1800, in: Climate since AD 1500, edited by: Bradley, R. S. and Jones, P. D., Routledge, London and New York, 92–117, 1992.

Ogilvie, A. E. J.: Sea-ice conditions off the coasts of Iceland AD 1601–1850 with special reference to part of the Maunder Minimum period (1675–1715), AmS-Varia, 25, 9–12, 1996.

Ogilvie, A. E. J., Barlow, L. K., and Jennings, A. E.: North Atlantic climate c. AD 1000: Millennial reflections on the Viking discoveries of Iceland, Greenland and North America, Weather, 55, 34–45, https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1477-8696.2000.tb04028.x, 2000.

Ogilvie, A. E. J. and Jónsson, T.: “Little Ice Age” research: A perspective from Iceland, Climatic Change, 48, 9–52, https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1005625729889, 2001.

Ojala, A. E. and Alenius, T.: 10,000 years of interannual sedimentation recorded in the Lake Nautajärvi (Finland) clastic–organic varves, Palaeogeogr. Palaeocl., 219, 285–302, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.palaeo.2005.01.002, 2005.

Ólafsdóttir, S., Jennings, A. E., Geirsdóttir, Á., Andrews, J., and Miller, G. H.: Holocene variability of the North Atlantic Irminger current on the south-and northwest shelf of Iceland, Mar. Micropaleontol., 77, 101–118, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marmicro.2010.08.002, 2010.

Ólafsson, J.: Physical characteristics of Lake Mývatn and River Laxá, Oikos, 32, 38–66, https://doi.org/10.2307/3544220, 1979.

Ono, M., Sawada, K., Shiraiwa, Y., and Kubota, M.: Changes in alkenone and alkenoate distributions during acclimatization to salinity change in Isochrysis galbana: Implication for alkenone-based paleosalinity and paleothermometry, Geochem. J., 46, 235–247, https://doi.org/10.2343/geochemj.2.0203, 2012.

Opel T., Laepple T., Meyer H., Dereviagin A. Y., and Wetterich S.: Northeast Siberian ice wedges confirm Arctic winter warming over the past two millennia, Holocene, 27, 1789–1796, https://doi.org/10.1177/0959683617702229, 2017.

Orme, L. C., Miettinen, A., Divine, D., Husum, K., Pearce, C., Van Nieuwenhove, N., Born, A., Mohan, R., and Seidenkrantz, M. S.: Subpolar North Atlantic sea surface temperature since 6 ka BP: Indications of anomalous ocean-atmosphere interactions at 4–2 ka BP, Quat. Sci. Rev., 194, 128–142, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2018.07.007, 2018.

Otto-Bliesner, B. L., Brady, E. C., Fasullo, J., Jahn, A., Landrum, L., Stevenson, S., Rosenbloom, N., Mai, A., and Strand, G.: Climate variability and change since 850 CE: An ensemble approach with the Community Earth System Model, B. Am. Meteorol. Soc., 97, 735–754, https://doi.org/10.1175/BAMS-D-14-00233.1, 2016.

PAGES 2K Consortium: Continental-scale temperature variability during the past two millennia, Nat. Geosci., 6, 339–346, https://doi.org/10.1038/ngeo1797, 2013.

PAGES 2K Consortium: Consistent multi-decadal variability in global temperature reconstructions and simulations over the Common Era, Nat. Geosci., 12, 643–649, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41561-019-0400-0, 2019.

Pla, S. and Catalan, J.: Chrysophyte cysts from lake sediments reveal the submillennial winter/spring climate variability in the northwestern Mediterranean region throughout the Holocene, Clim. Dynam., 24, 263–278, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00382-004-0482-1, 2005.

Planet Labs Inc.: Homepage, available at: https://www.planet.com/, last access: 14 April 2021.

Prahl, F. G. and Wakeham, S. G.: Calibration of unsaturation patterns in long-chain ketone compositions for palaeotemperature assessment, Nature, 330, 367–369, https://doi.org/10.1038/330367a0, 1987.

Prahl, F. G., Muehlhausen, L. A., and Zahnle, D. L.: Further evaluation of long-chain alkenones as indicators of paleoceanographic conditions, Geochim. Cosmochim. Ac., 52, 2303–2310, https://doi.org/10.1016/0016-7037(88)90132-9, 1988.

Ran, L., Jiang, H., Knudsen, K. L. and Eiríksson, J.: Diatom-based reconstruction of palaeoceanographic changes on the North Icelandic shelf during the last millennium, Palaeogeogr., Palaeocl., 302, 109–119, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.palaeo.2010.02.001, 2011.

Rehfeld, K., Trachsel, M., Telford, R. J., and Laepple, T.: Assessing performance and seasonal bias of pollen-based climate reconstructions in a perfect model world, Clim. Past, 12, 2255–2270, https://doi.org/10.5194/cp-12-2255-2016, 2016.

Richter, N., Longo, W. M., George, S., Shipunova, A., Huang, Y., and Amaral-Zettler, L.: Phylogenetic diversity in freshwater-dwelling Isochrysidales haptophytes with implications for alkenone production, Geobiology, 17, 272–280, https://doi.org/10.1111/gbi.12330, 2019.

Richter, N., Russell, J. M., Garfinkel, J., and Huang, Y.: Impacts of Norse settlement on terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems in Southwest Iceland, J. Paleolimnol., 65, 255–269, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10933-020-00169-3, 2021 (data available at: https://www.ncdc.noaa.gov/paleo/study/29992, last access: 14 April 2021).

Salacup, J. M., Farmer, J. R., Herbert, T. D., and Prell, W. L.: Alkenone Paleothermometry in Coastal Settings: Evaluating the Potential for Highly Resolved Time Series of Sea Surface Temperature, Paleoceanogr. Paleocl., 34, 164–181, https://doi.org/10.1029/2018PA003416, 2019.

Schmidt, G. A., Jungclaus, J. H., Ammann, C. M., Bard, E., Braconnot, P., Crowley, T. J., Delaygue, G., Joos, F., Krivova, N. A., Muscheler, R., Otto-Bliesner, B. L., Pongratz, J., Shindell, D. T., Solanki, S. K., Steinhilber, F., and Vieira, L. E. A.: Climate forcing reconstructions for use in PMIP simulations of the last millennium (v1.0), Geosci. Model Dev., 4, 33–45, https://doi.org/10.5194/gmd-4-33-2011, 2011.